Zur Geschichte und Zukunft von Schulden

„The History and Future of Debt“ lautet der Titel der diesjährigen Studie der Deutschen Bank zu den langfristigen Renditen von Anlageklassen. Bei diesem Titel dürfte allen Lesern von bto klar sein, dass ich nicht darum herumkomme, mich mit der Studie zu beschäftigen. Schon im letzten Jahr, als es um Inflation ging, habe ich die Studie hier ausführlich besprochen. Diesmal also das wohl entscheidendste Thema dieser Tage: die Verschuldung. Bekanntlich meiner Meinung nach, dass wohl größte Problem unserer Zeit, zeigen sich die Folgen doch in vielen Bereichen. Von dem geringen Wachstum bis hin zur Blasenbildung und zur Vermögensverteilung.

Schauen wir uns an, was die Analysten der Deutschen Bank dazu sagen:

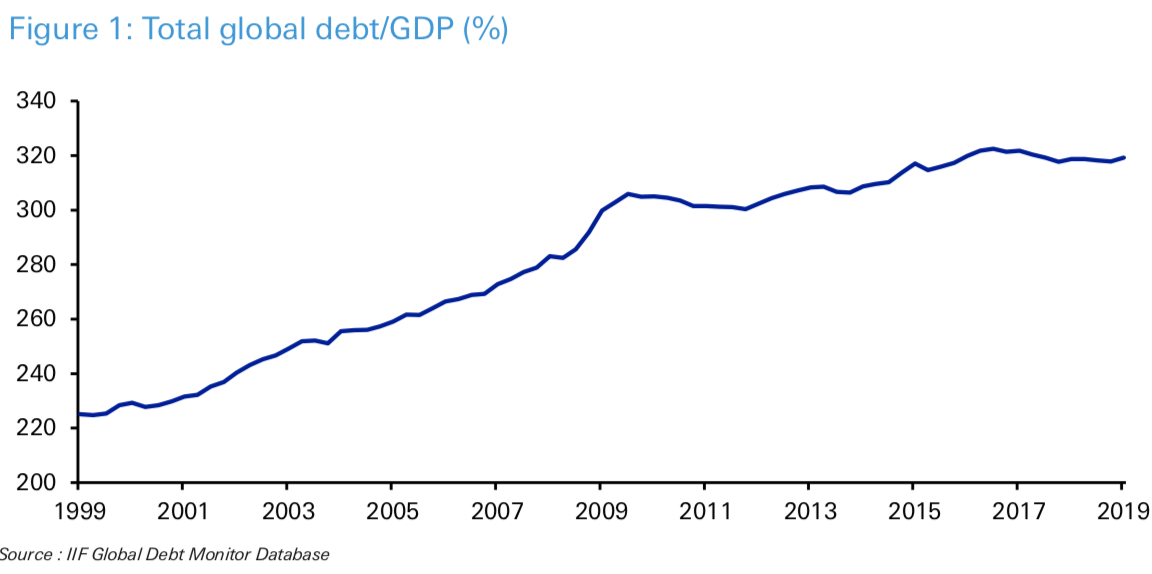

- Zunächst die bekannte Tatsache: „In total the world has $246.5 trillion of debt, up from around $172 trillion on the eve of the GFC and ‘only’ $84 trillion at the start of this century. Over the same three periods, global debt/GDP has grown from 228% (2000) to 300% (2009) and then to 319% in 2019.” – bto: Allein schon das Verlangsamen des Schuldenwachstums hat sich in geringen Wachstumsraten niedergeschlagen. Und dies übrigens auch trotz der Politik des billigen Geldes! Das Bild sieht eigentlich ganz harmlos aus:

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

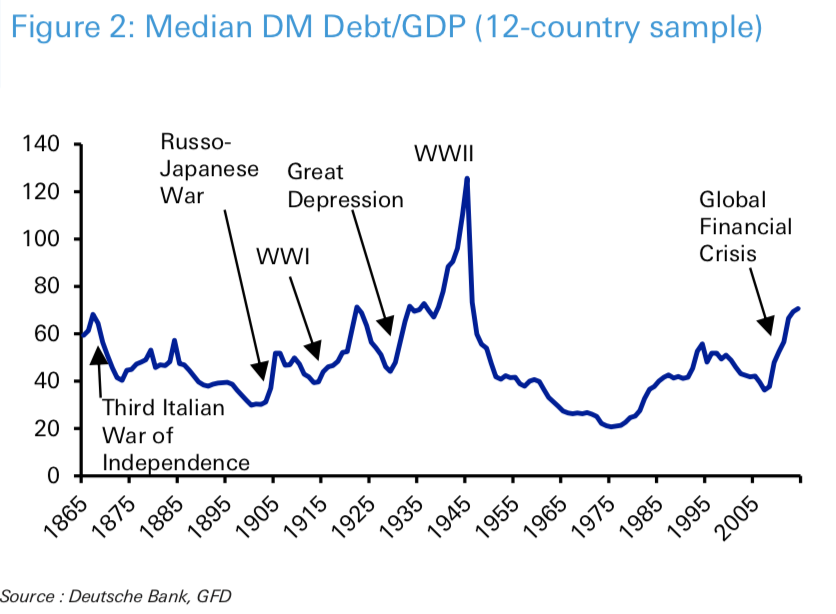

- „Total global debt/GDP (including non-government debt) has never been higher, but we have seen many governments carry higher debt/GDP in the past than current levels, although only around war times. Over the last few years, however, we’ve seen the highest peacetime levels of debt for much of the developed world.“ – bto: Und in gewisser Weise befinden wir uns in ähnlichen Zeiten. Zwar liegt die Ursache der hohen Staatsverschuldung in früherer Misswirtschaft und vor allem der Finanzierung überbordender Sozialleistungen. Der Anstieg seit 2008 ist aber auch als Folge der Finanzkrise zu sehen, weil Staaten, die (zu hohe) Verschuldung des Privatsektors im Zuge der Bilanzrezession kompensierten.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- Die Bank hält richtigerweise fest: „The debt floodgates opened after the 1971 aban- donment of the gold-based Bretton Woods system, and compound deficits have been the norm since. At the start of this period, overall global debt levels were around all-time lows and governments had a ‘free debt lunch’ until the GFC changed the landscape. Over the same period, private sector debt has also gone from low levels to record highs. So we are now in uncharted territory with unconventional policy to support high debt levels becoming increasingly normal.” – bto: Ich würde ergänzen, dass es nicht nur der Abgang von Bretton Woods war, sondern auch die Deregulierung des Finanzgeschäfts, was zur “financialization” geführt hat. Zu dem Zustand, dass mit Finanzgeschäften mehr Geld zu verdienen war, als mit realwirtschaftlicher Aktivität.

- „The main ways to de-lever through history have been to a) default, b) run large primary surpluses for extended periods, c) keep real yields negative or d) ensure nominal yields are well below nominal GDP. In general, it’s been a combination of the above.” – bto: Was in der Aufzählung zumindest explizit fehlt, ist “Back to Mesopotamia”, also die Lösung über Vermögensabgaben/Enteignung. Themen, die bekanntlich auch wieder auf den Tisch kommen.

- „(…) the first two seem completely unpalatable for the way we live and invest. Given how much debt there is and how systemic it seems to be, the authorities’ desire to see wide-scale debt restructuring seems minimal at this point. The fear would be that allowing restructuring in one over-indebted entity could create fears of a domino impact elsewhere. Debt is viewed as too systemic to our economic system. It’s not clear that this will change as debt piles get higher.” – bto: Natürlich sind die Schulden mittlerweile der entscheidende Treiber für Wachstum geworden, wenn auch mit immer geringerer Wirkung, wie bei bto häufig gezeigt. Es ist im Kern immer die berechtigte Angst vor der Fisherschen Schulden-Deflation. Diese zu stoppen, ist entscheidend.

- Nur in früheren Jahrhunderten war es denkbar, über längere Zeit mit Primärüberschüssen zu arbeiten, so Großbritannien nach den Napoleonischen Kriegen. Die Ausnahme in der Gegenwart ist Italien, mit den bekannten Folgen: „Italy is a modern-day exception, but three decades of near-continuous primary surpluses have contributed to a lack of investment in the economy, weak growth, still-rising debt, and persistent political instability culminating in the recent populist movements.” – bto: und haben nichts gebracht! Man kann sich aus dem Zustand der (Über-)schuldung nicht heraussparen. Dieses Bild sollten alle, die Deutschland loben und Italien kritisieren, genauer anschauen. Es zeigt die Primärüberschüsse der letzten Jahre:

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

„The biggest and most successful global deleveraging through history occurred between1945 and 1980, when yields could be set significantly below nominal GDP. Real yields weren’t consistently negative but saw periods where they were.” – bto: Das führt zur Frage, woher wir heute hohe nominale Wachstumsraten bekommen sollen: Die Erwerbsbevölkerung beginnt zu schrumpfen, die Produktivitätsfortschritte sind gering (und rückläufig) und die Inflationsraten, nicht zuletzt wegen der deflationären Wirkung hoher Schulden, gering und weiter fallend. Trotz der Bemühungen der Zentralbanken, sie zu beleben.

Die Abbildung zeigt sehr schön die Jahrzehnte der financial repression nach dem II. Weltkrieg.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “(…) the post-WWII era saw much higher levels of GDP growth due to favourable demographics, post-war reconstruction, and high productivity growth. It will be nearly impossible to manufacture a repeat of such an outcome. We will only get closer to it with significant ‘artificial’ fiscal and central bank interventions.” – bto: So ist es und wir wissen schon jetzt, dass die Weichen in diese Richtung gestellt werden.

- “Whether such central bank money printing ever gets repaid or is simply inflated away is open to debate (bto: natürlich ist Inflation oder Anullierung die “Lösung”. Zurückzahlen? Da kann man doch nur lachen, was aber in der Lage nicht richtig wäre.). Already since the GFC, government debt has effectively declined in many countries if you assume QE is never repaid. But by their aggressive actions over the last decade, central banks have effectively trapped themselves into continually intervening in government bond markets. They’re arguably beyond the point of no return. If the negative gap between government yields and nominal GDP is lost, then the global debt pyramid is on very shaky ground.” – bto: Die Schulden sind in den letzten Jahren relativ zum BIP langsamer gewachsen als bisher. Zum Teil auch dank der bereits stattfindenden financial repression. Besonders eindrücklich ist die Entwicklung in Japan, wie man in der nächsten Abbildung sieht. Dort wird man wohl als Erstes die offizielle Ausbuchung vornehmen, die von Leuten wie Adair Turner schon länger propagiert wird.

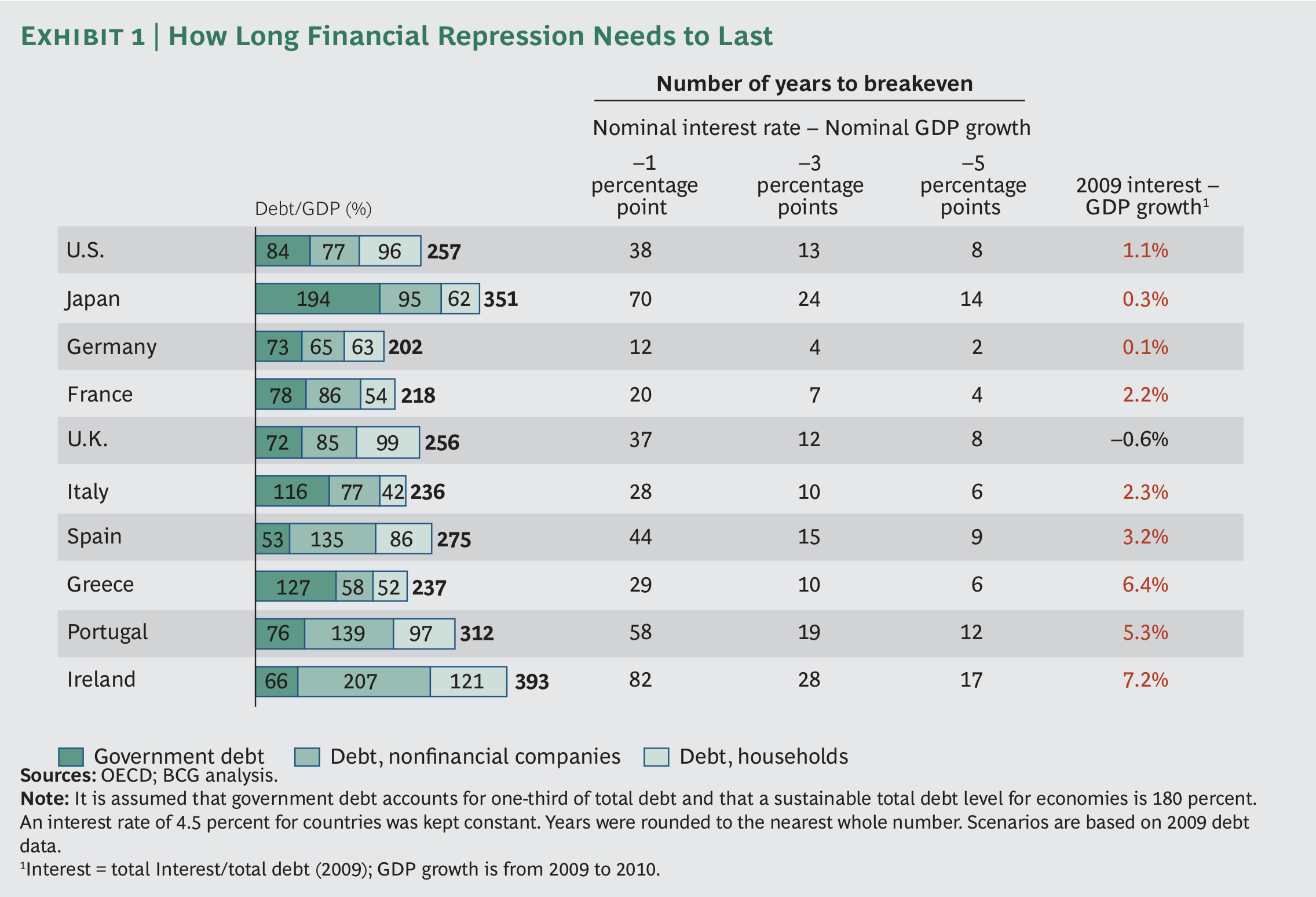

- „If yields can be suppressed for a long period, then debt ratios could grow at a much milder rate than official independent central-case scenarios. Even the high-spending US could stabilise debt if yields tended towards zero. (…) A word of caution, though: they would need to maintain this for a generation and perhaps longer to stop debt from rising notably – and that’s assuming no additional spend- ing. That’s no easy task and likely to require aggressive intervention and balance sheet expansion along the way.“ – bto: Der zweite Teil des Zitats kommt viel später in der Studie, ist aber hoch relevant. Wenn die Regierungen dies machen wollen, müssen sie über eine Generation hinweg finanzielle Repression betreiben. Das habe ich schon vor fast zehn Jahren – damals noch bei BCG – vorgerechnet. Heute sind die Zahlen ähnlich:

Quelle: BCG

- The further out you go, the more demographics become very challenging for debt sustainability across all parts of the globe. The big problem with this financial-repression scenario is that unless nominal GDP is increased from current low levels, negative/ultra-low rates would need to be locked in for a very long period, which may be counterproductive in other ways. The best chance of successful debt/economic management is NGDP staying notably higher than yields, but with both at higher levels than at present. Inflation might be the easier route than real GDP growth to achieve this (…).” – bto: Da pflege ich immer zu sagen: Wenn es leicht wäre, Inflation zu erzeugen, hätten wir sie schon längst. Es ist aber schwer vor dem Hintergrund der vielfältigen deflationären Kräfte, wie Zombies, Überkapazitäten, Demografie und Verschuldung.

Die negative Wirkung der Schulden auf das Wachstum diskutiert auch die Deutsche Bank:

- “The hardest part of this equation would be to create notably higher real GDP growth. Demographics alone make this arithmetically more difficult than it has been in previous de-leveraging periods. Numerous academic papers have been written to explain the multi-decade slowdown in productivity, and it is beyond the scope of this report to assess how productivity could improve. While this is a deeply complex issue, we can’t help but wonder whether the debt burden itself plays a large part in the productivity slump we find ourselves in.” – bto: Ich bin davon überzeugt, weil die Schulden immer unproduktiver verwendet werden. Es ist eine natürliche Folge abnehmenden Schuldendrucks – immer billiger und leichter umzuschulden –, der Zombifizierung und der Verwendung des Geldes, um vorhandene Vermögenswerte zu immer höheren Preisen zu kaufen.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- Im Falle Deutschlands sehen die Experten noch deutlichen Verschuldungsspielraum: “Germany has extremely low funding costs of just over 1% of GDP and is forecast to run a primary surplus at 1.5-2.0pp of GDP for the next few years. Since current yields are even lower than current funding costs, the average cost of the debt will likely continue to fall. Even without such a fall, the IMF forecasts that debt will fall by 2.5-3.0pp of GDP every year for the next several years. Accordingly, Germany could in theory accommodate average funding costs as high as 5-6% over the next decade and keep debt/GDP stable.” – bto: ein weiteres Argument gegen die schwarze Null. Ich bin überzeugt, dass wir große Defizite sehen werden, leider für soziale Dinge und Projekte mit geringem ökonomischem Nutzen.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “We appreciate that there is little political appetite for this in Germany at the moment, but things evolve and a recession or an economic threat to the European Union could change everything. For completeness, we should say that demographics become less favourable for Germany (along with much of Europe) the further you go out, so it will be difficult to stabilise debt and spend indefinitely.” – bto: vor allem wenn man betrachtet, was für Versprechen in den letzten Jahren gemacht wurden!

- Dann kommen die Analysten zu einer weiteren entscheidenden Frage: Wer lässt sich freiwillig enteignen, in dem er sich mit Zinsen unterhalb der nominalen Wachstumsrate zufriedengibt? In den 1950er-Jahren war die Regulierung der Anlagen weitaus strikter und zugleich die Transparenz nicht so gegeben. Heute wäre eine Flucht aus dem System möglich, wobei bekanntlich die Maßnahmen immer offensichtlicher werden, wie zum Beispiel die schleichende Abschaffung von Bargeld. „(…) can governments get away with keeping yields so low relative to activity? In their favour is the rapid increase over the last couple of decades in the non-price-sensitive holders of government bonds. As well as domestic central banks, the foreign sector owns an increasing amount of bonds. Much of this is due to the huge accumulation of reserves around the world, especially from EM countries. If globalisation falters, though, domestic central banks may have to intervene even more in the future to offset declining reserve flows.” – bto: Es sind also schon die Zentralbanken, die die Anleihen halten. Dennoch spielen die Nicht-Banken immer noch eine erhebliche Rolle. Damit sind die Verlierer jene, die ihr Geld in Lebensversicherungen und Pensionsfonds halten, die entsprechend mit negativen Realrenditen arbeiten.

- “(…) what happens if and when policy makers are actually successful and generate inflation. At the moment, those investors have been kept onside by extraordinary recent fixed income returns. (…) as investors have been able to sell to people who think yields will go even deeper into negative territory or that we’re in for semi-permanent global ‘Japanification’. So economic success and a free-float bondholder rebellion might be the biggest risk to this policy avenue over the next decade or so. (…) To maintain debt sustainability and control the rise in yields when fiscal spending increases, central bank holdings of government bonds (and private sector bonds) will likely need to climb ever higher in the years ahead.” – bto: Da jeder Zinsanstieg einem globalen Margin Call gleichkommt, müssen die Notenbanken alles daran setzen, die Zinsen unten zu halten. Das bedeutet, sie werden praktisch alles kaufen, was zugleich den Verkaufsdruck erhöht, weil mit immer höheren Käufen das Vertrauen in die Geldordnung abnimmt und damit die Flucht zunimmt. Jeder, der nicht gezwungen ist, diese Papiere zu halten, wird aussteigen.

- “(…) there will be one big loser – bond holders. Real wealth was destroyed in this period (1945 – 1980) for those invested in government bonds. Commodities could be the best future performer relative to their usual levels of return if past is prologue. Demand for alternative currencies (e.g. crypto) would clearly rise if this scenario plays out.” – bto: Ich denke, man muss sehr aufpassen bei dieser Prognose. Aktien sind bereits sehr hoch bewertet und dürften im Falle einer wirklichen Inflation unter Druck geraten (außer die Notenbanken entschulden auch die Unternehmen). Öl dürfte nicht wieder so gut abschneiden, befinden wir uns doch auf dem Weg in Carbon-Neutralität. Insofern dürften die Bereiche, in die das Geld des Staates fließt, interessant sein. Immobilien werden einer stärkeren Regulierung unterliegen und mehr besteuert werden, damit die Politik zeigen kann, dass sie alle Bevölkerungsschichten trifft.

- “At normalised interest rates, it would likely be just a matter of time before we saw a huge global debt crisis. With yields close to zero or in negative territory across the majority of the globe, it’s possible to comfortably run much higher levels of debt than past textbooks would have suggested and reduce the scale of its accumulation.” – bto: Bekanntlich sehe ich das genauso. Allerdings würde ich widersprechen und keineswegs sehen, dass das Wachstum der Schulden damit abnimmt. Ich denke, die letzten Jahre waren der vergebliche Versuch, etwas auf die Bremse zu gehen. Zugleich haben wir bei den Unternehmen, namentlich in den USA, gesehen, dass das billige Geld einen starken Anreiz darstellt, sich höher zu verschulden. Damit mögen tiefe Realzinsen zwar zur Entschuldung beitragen, zugleich aber weitere Verschuldung beschleunigen. Da springt die Deutsche Bank also zu kurz.

- “With funding so easy and populism so high, the temptation will build amongst politicians towards helicopter- money policies and what amounts to even more debt. Zero-percent perpetuals do not seem too far away. In general, though, it feels like an environment in which issuers of debt should try to fix in ultra-low, ultra-long funding, and investors – where possible – should avoid buying it. Is that a sustainable equilibrium?” – bto: Wir kennen die Antwort. Natürlich nicht. Aber wir wissen zumindest mal, wie es in den kommenden Jahren weitergeht.

- Dafür zeigen sie auf, wie gut der „fiskalische Multiplikator“ wirkt, besonders dann, wenn die Zinsen schon nahe null liegen: „(…) the fiscal multiplier is usually higher when the economy is operating below potential and monetary policy is constrained by the zero lower bound. The IMF recently published research estimating the multiplier for Europe under normal conditions, i.e. interest rates well above zero, and under effective lower bound conditions, i.e. the current environment with policy rates below zero. The results are shown in the chart below, and while it’s very difficult to calculate where we currently are on the normal to lower bound scale, we are probably closer to the latter where the fiscal multiplier is likely to be much higher even if levels above 2 seem very high.” – bto: Das leuchtet auch ein, ohne dass man eine solche Berechnung durchführt. In diesem Umfeld muss eine Staatsnachfrage wirken. Entscheidend ist dabei allerdings die Annahme, dass wir wirklich nicht ausgelastet sind. Ist diese falsch, müsste es inflationär wirken und damit wäre aus dem Blickwinkel der Schulden ja auch etwas gewonnen.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- Dabei wissen auch die Deutschbanker um die Umverteilungswirkung solcher Maßnahmen in der Eurozone, übrigens ohne jegliche demokratische Legitimierung: “(…) the euro area has a complicated system of interlocking national cen- tral banks. It would likely be possible for the Eurosystem to implement a helicopter money/MMT-like system, but it would likely require further socialising of risks. (…) this would likely result in even wider Target II imbalances. Countries with large fiscal deficits, like Italy (2018 deficit of -2.1% of GDP), France (-2.5%), and Spain (-2.5%), would likely lean on their central banks for additional reserve creation. On the other hand, surplus countries like Germany (+1.7%) and the Netherlands (+1.5%), would not need as much monetary support.” – bto: Die TARGET2-Salden werden explodieren und damit wird die Risikoverschiebung deutlich zunehmen. Andererseits gibt es ja immer noch Stimmen, die behaupten, es handle sich nur um eine Buchhaltungsposition. Sehe ich anders.

- Was zum Fazit führt: “(…) helicopter money or MMT-type policies have a chance of working for the economy only if they can create a scenario where real yields stay negative (preferably by a decent margin) and nominal GDP growth stays comfortably above nominal yields. The aim is to increase nominal GDP without increasing nominal yields by as much (if at all, but that might be unrealistic). So the era of financial repression will need to stay and central banks will need to be aggressive. In an ideal world, you would increase real GDP, but that is as much a function of demographics and productivity. We have to assume demographics are generally getting worse across the MDW and that structural reforms are not only difficult but will generally move the needle by only a few tenths of a percentage point for most countries. As we hinted earlier, excess debt in the system might in itself be holding productivity back. So managing this debt burden relative to GDP might be the key to unlocking some productivity gains.” – bto: Das Problem dabei: Es dauert zu lange. Es sind Jahrzehnte nötig, in denen weiterhin Vermögenspreise hoch sind und das Gefühl fehlender Gerechtigkeit zunimmt. Damit kann es gut sein, dass Politik und Notenbanken die Zeit nicht haben, weil die Bevölkerung es nicht mitmacht.

Vorerst können wir uns auf das Grundszenario einstellen. Wir bekommen die Helikopter zugunsten einer Klimawende und müssen schauen, wie wir da durchnavigieren. Es ist der weitere Marsch in den Notenbanksozialismus, wie hier schon beschrieben. Eigentlich schade, dass die Analysten auch keine neuen Ideen aufgebracht haben. Die aktualisierten Fakten sind dennoch interessant.