Langfriststudie: Globales Immobilienportfolio und Aktien die beste Geldanlage

Es gibt schon seit Jahren Langfriststudien von Banken zu den Erträgen und Risiken verschiedener Anlageklassen. Nun kommt eine akademische Studie hinzu, die nicht nur mit der Länge der Analyse (mehr als 100 Jahre) und der Breite (inklusive Immobilien) beeindruckt.

“The rate of Return on Everything 1870-2015” von Òscar Jordà, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor, erschienen als NBER Working Paper 24112. Der Link wie immer am Ende.

Es war eine sehr interessante Feiertagslektüre. Hier die Highlights:

Zunächst die Zusammenfassung:

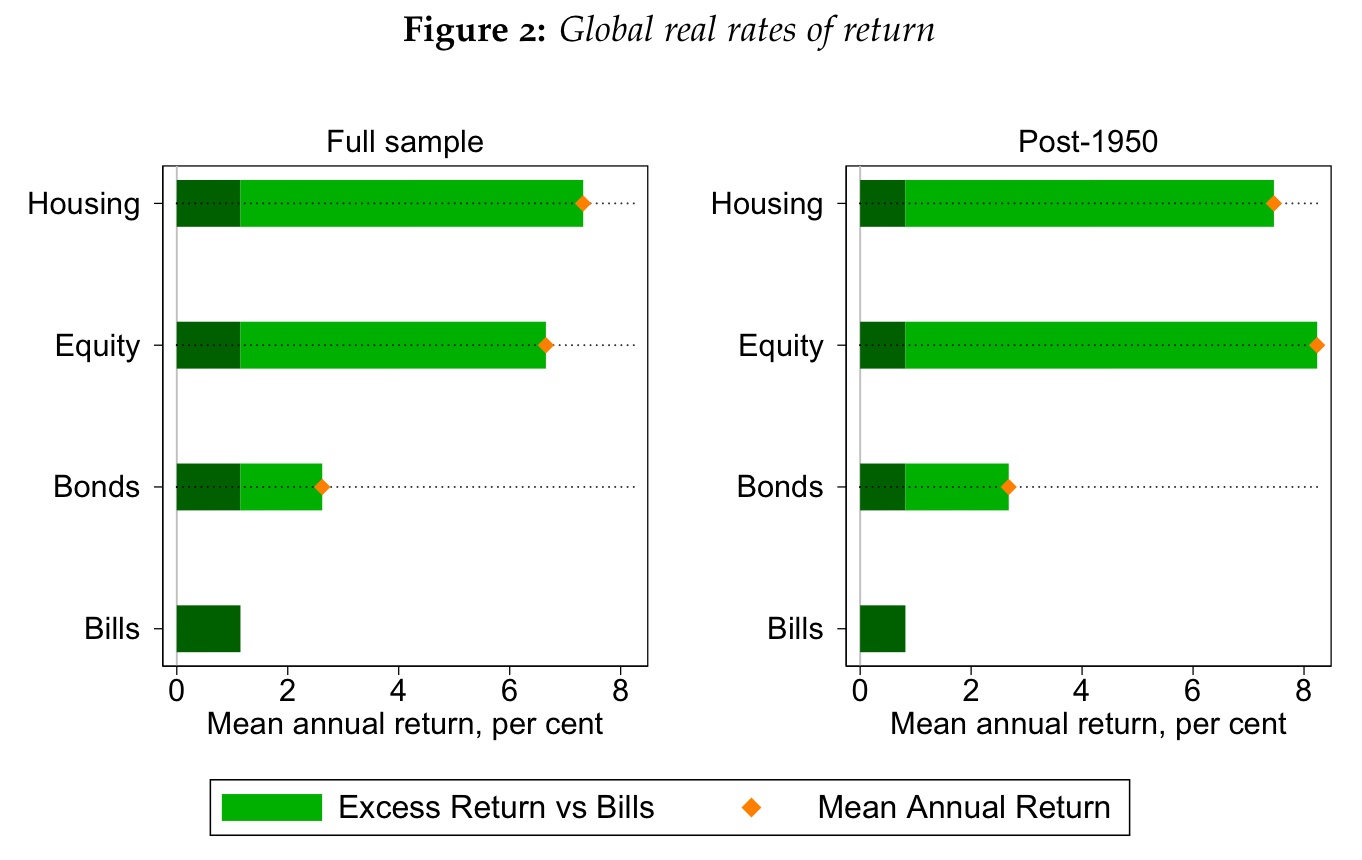

- “In terms of total returns, residential real estate and equities have shown very similar and high real total gains, on average about 7% per year. (…) The observation that housing returns are similar to equity returns, yet considerably less volatile, is puzzling. Diversification with real estate is admittedly harder than with equities.” – bto: Bisher wurde immer angenommen, dass Immobilien weniger abwerfen. (Vielleicht auch weil es Studien von Banken waren?)

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

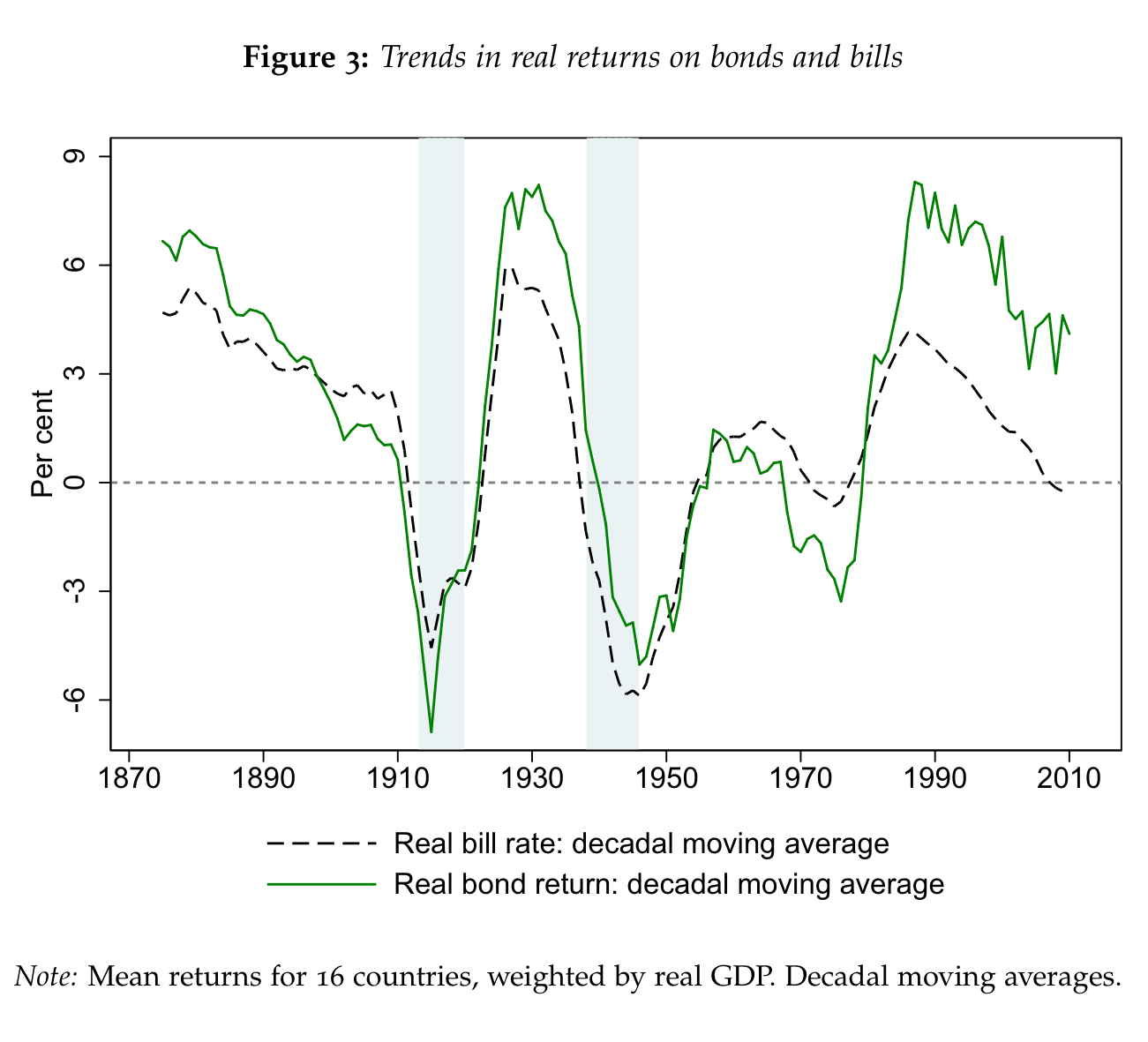

- “Before WW2, the real returns on housing and equities (and safe assets) followed remarkably similar trajectories. After WW2 this was no longer the case, and across countries equities then experienced more frequent and correlated booms and busts. The low covariance of equity and housing returns reveals significant aggregate diversification gains (i.e., for a representative agent) from holding the two asset classes.” – bto: was wiederum sehr interessant ist.

- “It is not just that housing returns seem to be higher on a rough, risk-adjusted basis. It is that, while equity returns have become increasingly correlated across countries over time (specially since WW2), housing returns have remained uncorrelated. Again, international diversification may be even harder to achieve than at the national level. But the thought experiment suggests that the ideal investor would like to hold an internationally diversified portfolio of real estate holdings, even more so than equities.” – bto: Das könnte ein interessantes Produkt für Kapitalanleger sein.

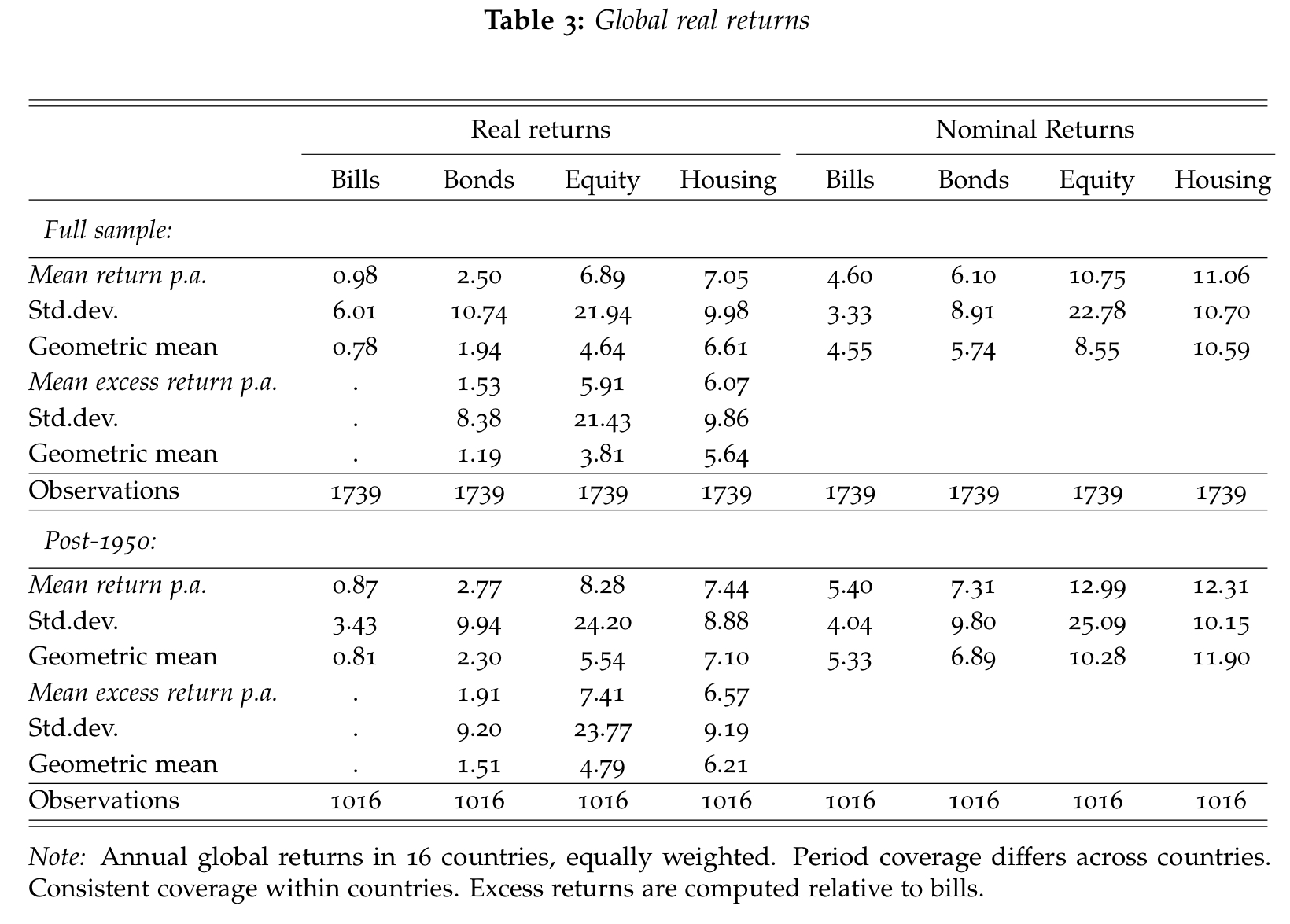

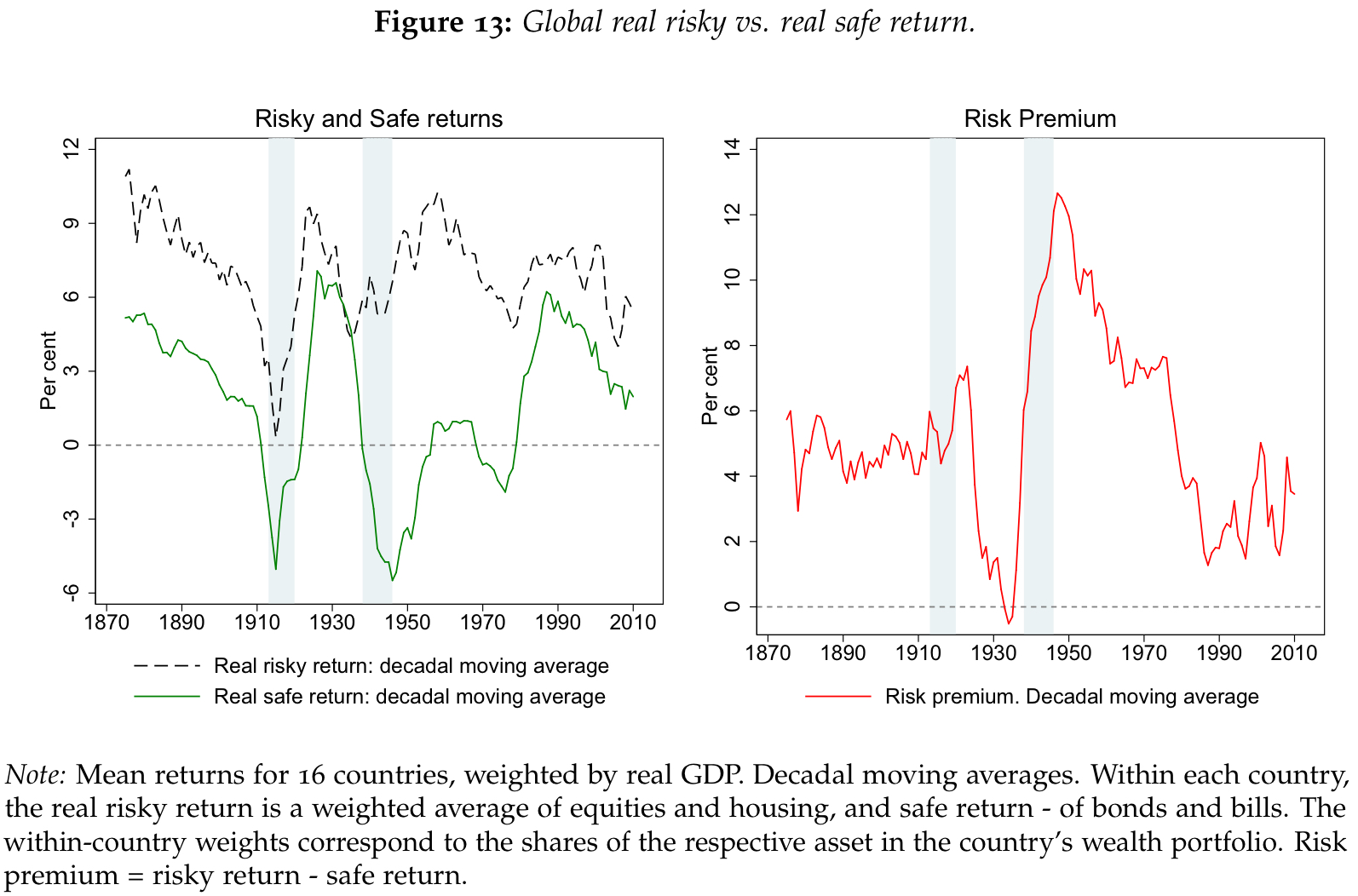

- “We find that the real safe asset return has been very volatile over the long-run, more so than one might expect, and oftentimes even more volatile than real risky returns. (…) Viewed from a long-run perspective, it may be fair to characterize the real safe rate as normally fluctuating around the levels that we see today, so that today’s level is not so unusual. Consequently, we think the puzzle may well be why was the safe rate so high in the mid-1980s rather than why has it declined ever since.” – bto: Das lässt die ganze Diskussion zur Rolle der Notenbanken in einem anderen Licht erscheinen. Wäre es doch der Markt, nicht die Notenbanken, die die tiefen Zinsen verursachen? Ich denke, die Argumentation hat etwas.

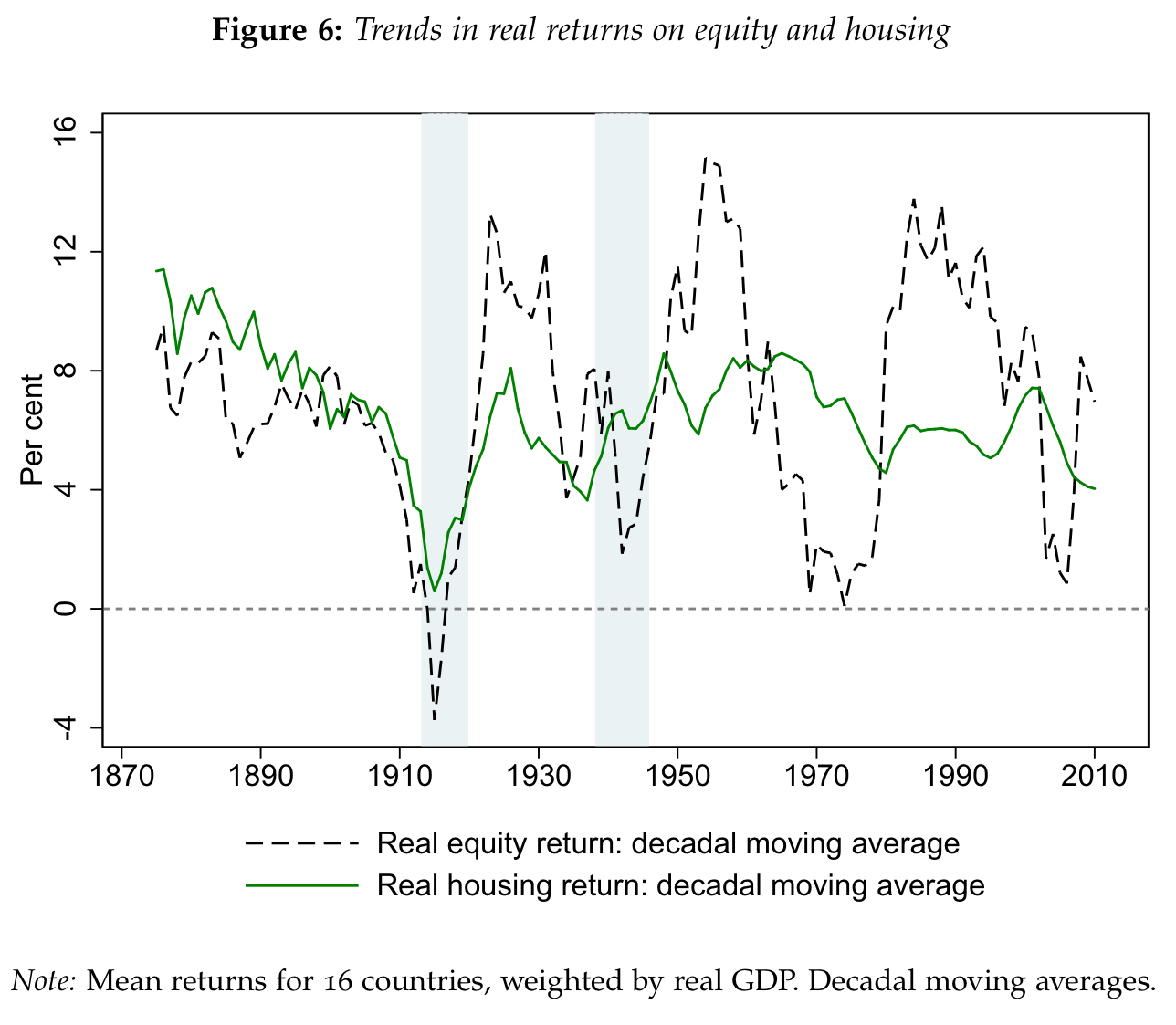

- “Over the very long run, the risk premium has been volatile. (…) In most peacetime eras this premium has been stable at about 4%–5%. (…) there is no visible long-run trend, and mean reversion appears strong. Curiously, the bursts of the risk premium in the wartime and interwar years were mostly a phenomenon of collapsing safe rates rather than dramatic spikes in risky rates. In fact, the risky rate has often been smoother and more stable than safe rates, averaging about 6%–8% across all eras.” – bto: Fand ich sehr interessant.

- “Recently, with safe rates low and falling, the risk premium has widened due to a parallel but smaller decline in risky rates. But these shifts keep the two rates of return close to their normal historical range. Whether due to shifts in risk aversion or other phenomena, the fact that safe rates seem to absorb almost all of these adjustments seems like a puzzle in need of further exploration and explanation.” – bto: Und es widerspricht der derzeitigen Diskussion zu Zinsniveau und Ursachen.

- Dann kommt noch als Zusatzanalyse die Frage nach der „Piketty-Regel“: “Turning to real returns on all investable wealth, Piketty (2014) argued that, if the return to capital exceeded the rate of economic growth, rentiers would accumulate wealth at a faster rate and thus worsen wealth inequality. Comparing returns to growth, or ‘r minus g’ in Piketty’s notation, we uncover a striking finding. Even calculated from more granular asset price returns data, the same fact reported in Piketty (2014) holds true for more countries and more years, and more dramatically: namely ‘r ≫ g.’” – bto: Das ziehe ich bekanntlich in Zweifel, weil es auch erhebliche Vermögensvernichtung gibt und der dahinterliegende Grund – der Leverage – vernachlässigt wird.

Und jetzt der tiefere Einstieg in die vielen interessanten Ergebnisse der Studie:

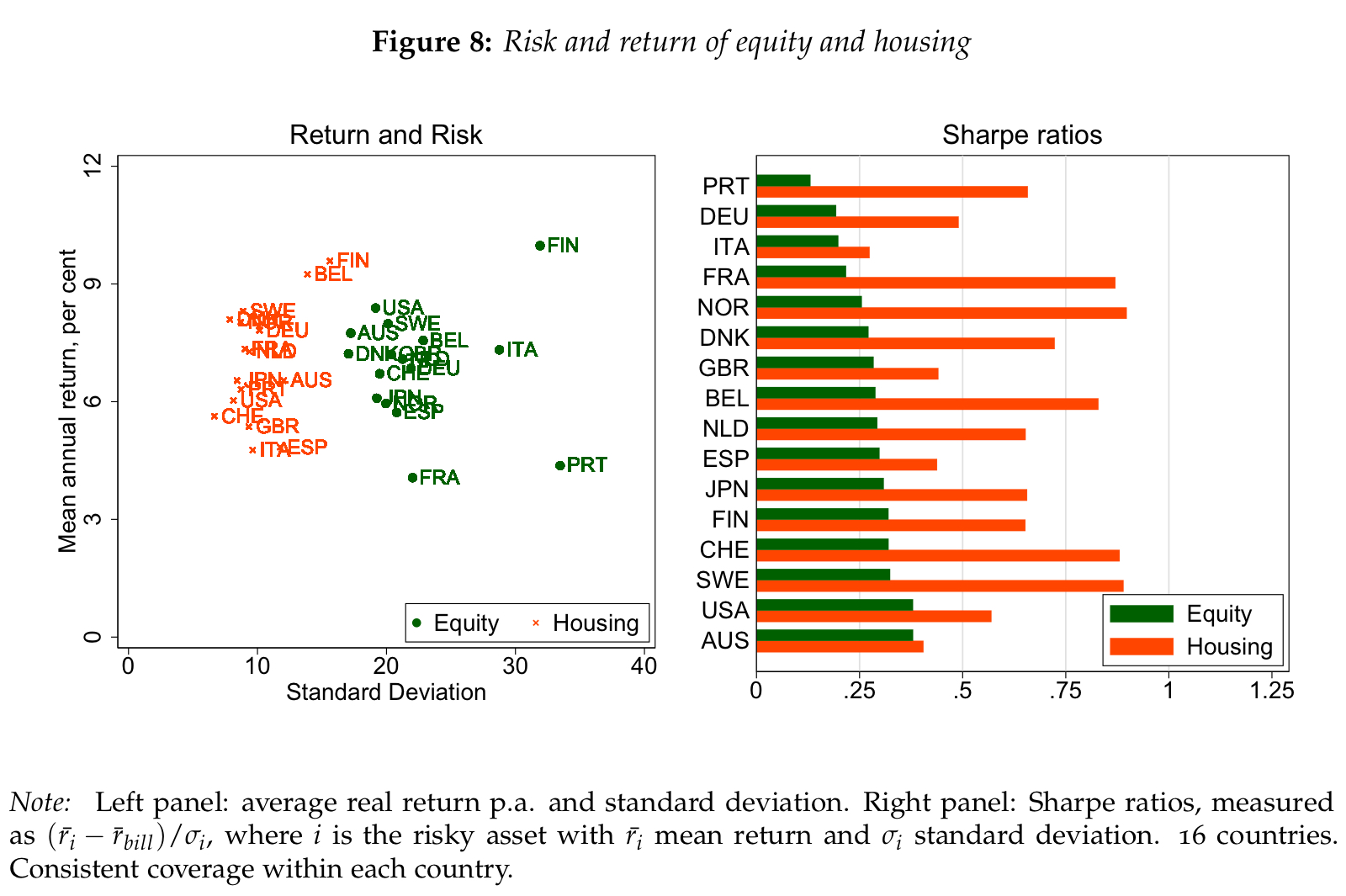

- “Although returns on housing and equities are similar, the volatility of housing returns is substantially lower, as Table 3 shows. Returns on the two asset classes are in the same ballpark — around 7% — but the standard deviation of housing returns is substantially smaller than that of equities (10% for housing versus 22% for equities). (…) This finding appears to contradict one of the basic assumptions of modern valuation models: higher risks should come with higher rewards.” – bto: wobei – wie gesagt – es nicht richtig ist, Risiko mit Volatilität gleichzusetzen. Ich denke, bei Immobilien gibt es weitaus mehr Risiken in Form von staatlichen Eingriffen und Besteuerungen.

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

- “Safe rates are far from stable in the medium-term. There is enormous time series, as well as cross-country variability. In fact, real safe rates appear to be as volatile (or even more volatile) than real risky rates, (…) Considerable variation in the risk premium often comes from sharp changes in safe real rates, not from the real returns on risky assets.””– bto: Es ist also vor allem der risikofreie Zins, der Unterschiede erklärt.

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

- “Returns dip dramatically during both world wars. It is perhaps to be expected: demand for safe assets spikes during disasters although the dip may also reflect periods of financial repression that usually emerge during times of conflict, and which often persist into peacetime. Thus, from a broad historical perspective, high rates of return on safe assets and high term premiums are more the exception than the rule.” – bto: Das ist gerade mit Blick auf die Geldpolitik sehr interessant. Es wäre dann besser, es zu akzeptieren, statt es mit immer mehr schädlichen Mitteln zu bekämpfen.

- “(…) during the late 19th and 20th century, real returns on safe assets have been low—on average 1% for bills and 2.5% for bonds—relative to alternative investments. Although the return volatility—measured as annual standard deviation—is lower than that of housing and equities, these assets offered little protection during high-inflation eras and during the two world wars, both periods of low consumption growth.” – bto: Das sollte eigentlich nicht überraschen. Es sind nun mal keine “Real-Assets” und deshalb unterliegen sie Kontrahenten- und Entwertungsrisiken.

- “(…) safe rates of return have important implications for government finances, as they measure the cost of raising and servicing government debt. What matters for this is not the level of real return per se, but its comparison to real GDP growth, or rsa f e − g. If the rate of return exceeds real GDP growth, rsa f e > g, reducing the debt/GDP ratio requires continuous budget surpluses. (…) Starting in the late 19th century, safe rates were higher than GDP growth, meaning that any government wishing to reduce debt had to run persistent budget surpluses. (…) After World War 2, on the contrary, high growth and inflation helped greatly reduce the value of national debt, creating rsa f e − g gaps as large as –10 percentage points.” – bto: Das hat natürlich auch mit der Loslösung des Geldes vom Gold zu tun! Inflation ist kein Zufall, sondern politisch erwünscht.

- “On average throughout our sample, the real growth rate has been around 1 percentage point higher than the safe rate of return (3% growth versus 2% safe rate), meaning that governments could run small deficits without increasing the public debt burden.” – bto: wie gesagt, die heimliche Steuer auf allen Ersparnissen zugunsten der „Allgemeinheit“ (oder er zugunsten der „Reichen“, die besser investieren können?)

- “Equity returns have experienced many pronounced global boom-bust cycles, much more so than housing returns, with real returns as high as 16% and as low as −4% over the course of entire decades.” – bto: was natürlich eigentlich zu höheren langfristigen Erträgen führen sollte, aber eben nicht tut. Könnte es sein, dass der Ertrag einfach der Ertrag ist und das Volatilitäts-gemessene Risiko ein anderes?

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

- “In terms of relative returns, housing persistently outperformed equity up until the end of WW1, even though the returns followed a broadly similar temporal pattern. In recent decades, equities have slightly outperformed housing on average, but only at the cost of much higher volatility and cyclicality. Furthermore, the upswings in equity prices have generally not coincided with times of low growth or high inflation, when standard theory would say high returns would have been particularly valuable.” – bto: eine sehr interessante Nachricht. Der vermeintliche Inflationsschutz ist mit Aktien nicht gegeben. Darauf habe ich in meiner Serie „Was tun mit dem Geld?“ übrigens auch schon hingewiesen.

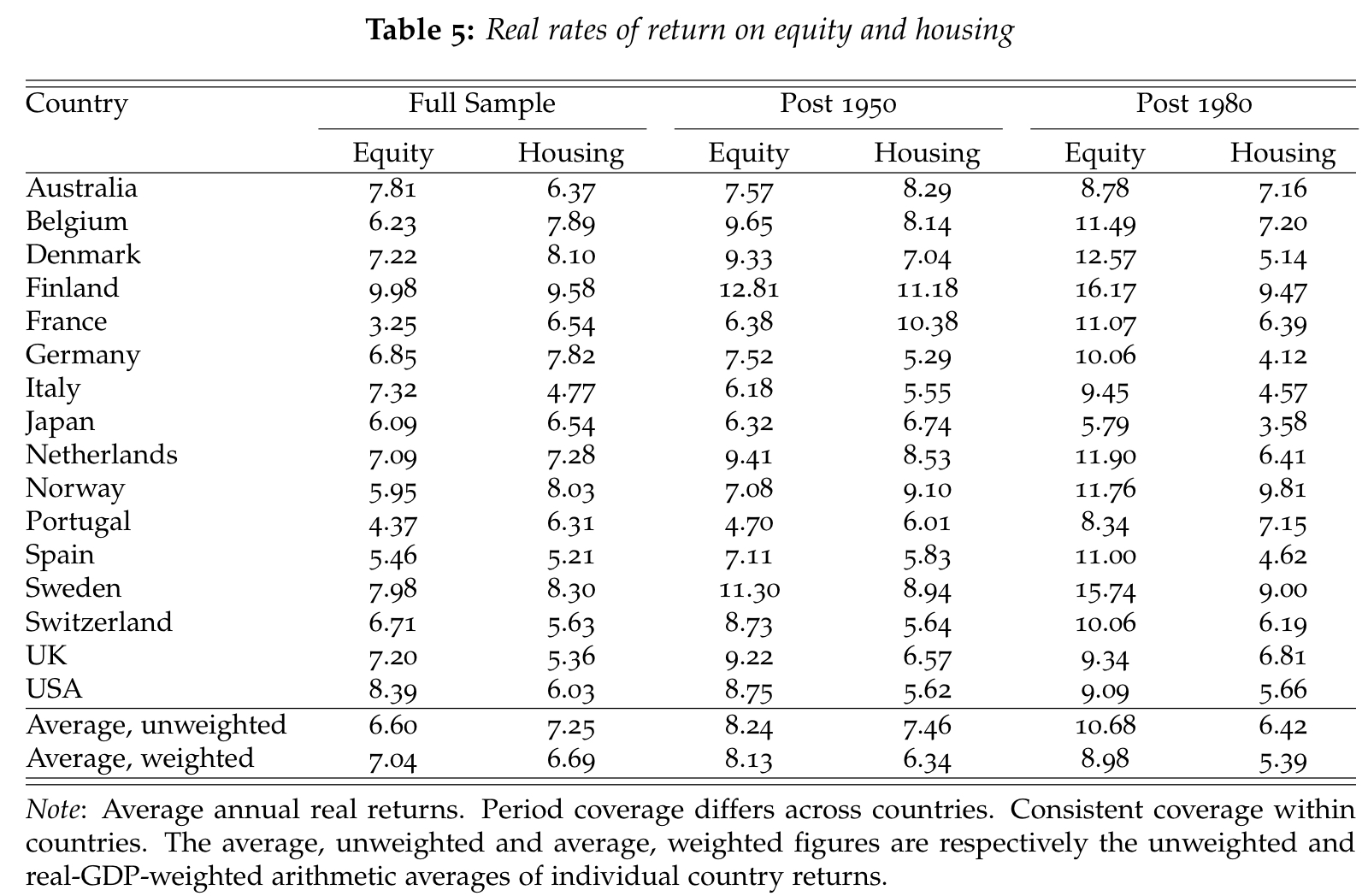

- “Table 5 shows the returns on equities and housing by country for the full sample and for the post–1950 and post–1980 subsamples. Long-run risky asset returns for most countries are close to 6%–8% per year, a figure which we think represents a robust and strong real return to risky capital.” – bto: in der Tat ein sehr erfreuliches Ergebnis. Doch auch hier kam es immer wieder zu Phasen erheblicher Vermögensvernichtung, auf die wir uns einstellen müssen. Gerade heute würde ich eine unzureichende Risikoprämie an den Märkten ausmachen. Dazu genügt ein Blick auf die Bewertungen im Bereich der High-Yield-Bonds. Wenn diese in Europa weniger abwerfen, als zehnjährige US-Staatsanleihen ist etwas nicht in Ordnung!

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

- “(…) equities do not outperform housing in simple risk-adjusted terms. Figure 8 compares the riskiness and returns of housing and equities for each country. The left panel plots average annual real returns on housing (orange crosses) and equities (green circles) against their standard deviation. The right panel shows the Sharpe ratios for equities (in dark green) and housing (in orange) for each country in the sample. Housing provides a higher return per unit of risk in each of the 16 countries in our sample, with Sharpe ratios on average more than double those of equities.” – bto: Das kann man auf dieser Abbildung sehr gut erkennen:

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

Aus Sicht des Investors stellt sich die Frage, wie man international in Immobilien diversifiziert anlegen kann. Ich denke dabei zwangsläufig an Immobilienaktien und REITS. Beides, besonders Letztere werden kritisch gesehen. Umso interessanter dieses Ergebnis der Studie:

- “Real estate investment trusts, or REITs, are investment funds that specialize in the purchase and management of residential and commercial real estate. (…) The return on these shares should be closely related to the performance of the fund’s portfolio, i.e., real estate. We would not expect the REIT returns to be exactly the same as those of the representative housing investment. The REIT portfolio may be more geographically concentrated, its assets may contain non-residential property, and share price fluctuations may reflect expectations of future earnings and sentiment, as well as underlying portfolio returns. (…) Figure 12 compares our historical housing returns (dashed line) with those on investments in REITs (solid line) in France and USA, two countries for which longer-run REIT return data are available.” – bto: Das bedeutet, dass man mit REITS (und Immobilienaktien) internationale Diversifizierung erreichen kann!

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

- Dabei vergessen die Autoren nicht ihre eigene Arbeit zum Thema Immobilienverschuldung: “(…)advanced economies in the second half of the 20th century experienced a boom in mortgage lending and borrowing. It is important to note that this surge in household borrowing did not only reflect rising house prices, but also reflected substantially increased household debt levels relative to asset values. Hence, the majority of households in advanced economies today hold a leveraged portfolio in their local real estate market. As with any leveraged portfolio, this significantly increases both the risk and return associated with the investment.” – bto: Das ist ein ganz wichtiger Punkt! Ein enormes Klumpenrisiko!

- “And today, unlike in the early 20th century, houses can be levered much more than equities, in the U.S. and in most other countries. The benchmark rent-price ratios from the IPD used to construct estimates of the return to housing, refer to rent-price ratios of unleveraged real estate. Consequently, the estimates presented so far constitute only un-levered housing returns of a hypothetical long-only investor, which is symmetric to the way we (and the literature) have treated equities.” – bto: Das bedeutet aber auch, dass die echten Eigenkapitalrenditen mit Immobilien deutlich höher waren und sind, was wiederum die ansteigenden Vermögenswerte erklärt!

- “Turning back to the trend in safe asset returns, even though the safe rate has declined recently, much as it did at the start of our sample, it remains close to its historical average. These two observations call into question whether secular stagnation is quite with us.” – bto: Also haben wir eine „normale Situation“ – naja, wenn man von der gigantischen Verschuldung absieht.

- “Interestingly, the period of high risk premiums coincided with a remarkably low frequency of systemic banking crises. In fact, not a single such crisis occurred in our advanced-economy sample between 1946 and 1973. By contrast, banking crises appear to be relatively more frequent when risk premiums are low. This finding speaks to the recent literature on the mispricing of risk around financial crises. (…) that when risk is underpriced, i.e. risk premiums are excessively low, severe financial crises become more likely. The long-run trends in risk premiums presented here seem to confirm this hypothesis.” – bto: so banal und einleuchtend!

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

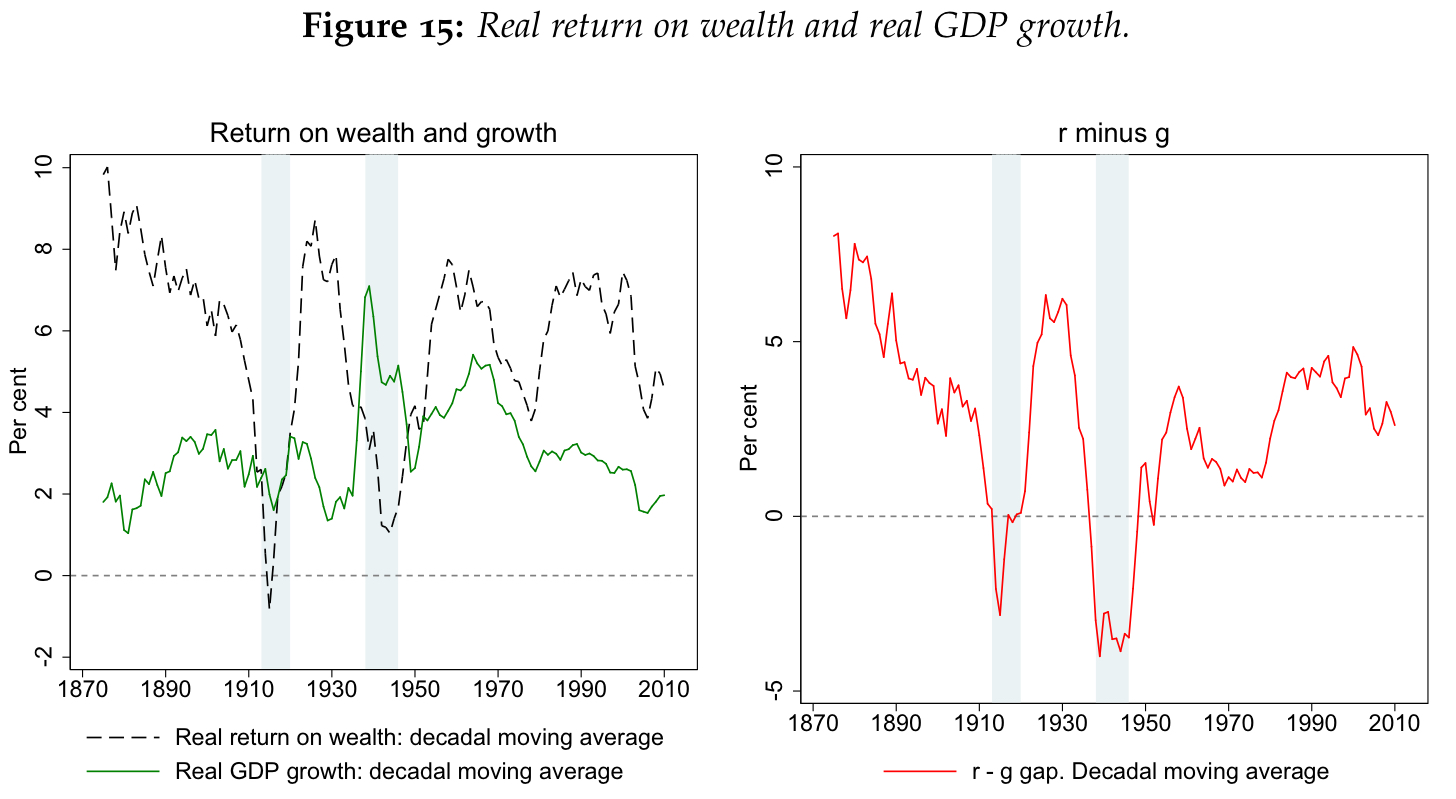

Dann geht es um die Frage, ob Piketty mit seiner Behauptung, dass der Ertrag von Kapital über der Wachstumsrate der Wirtschaft Recht hat. Kurze Antwort: Die Daten bestätigen die Analyse von Piketty, allerdings zeigen sich immer wieder Phasen erheblicher Kapitalvernichtung:

- “(…) Piketty and Zucman (2014) argue (…) that wealth inequality may continue to rise in the future, along with a predicted decline in the rate of economic growth. The main theoretical argument for this comes about from a simple relation: r > g. In their approach, a higher spread between the real rate of return on wealth, denoted r, and the rate of real GDP growth, g, tends to magnify the steady-state level of wealth inequality.” – bto: was ich in meinem kleinen Buch über Pikettys Thesen kritisiert habe. Ich denke, es kann nicht ewig so gehen, da zum einen auch Ertrag verbraucht wird, zum anderen Verluste entstehen. Wir konnten nur wegen des Leverage-Effektes den Anstieg der Vermögenswerte möglich machen.

- “Our data show that the trend long-run real rate of return on wealth has consistently been higher than the real GDP growth rate. Over the past 150 years, the real return on wealth has substantially exceeded real GDP growth in 13 decades, and has only been below GDP growth in the two decades corresponding to the two world wars. That is, in peacetime, r has always exceeded g. The gap between r and g has been persistently large. Since 1870, the weighted average return on wealth (r) has been about 6.0%, compared to a weighted average real GDP growth rate (g) of 3.1%, with the average r − g gap of 2.9 percentage points, which is about the same magnitude as the real GDP growth rate itself. The peacetime gap between r and g has been around 3.6 percentage points.” – bto: Das führte aber eben doch zu einer Gegenreaktion, sonst wären die Vermögenswerte nicht so konstant wieder zurückgegangen.

- “(…) the initial difference between r and g of about 5–6 percentage points disappeared around WW1, and after reappearing briefly in the late 1920s, remained modest until the 1980s. After 1980, returns picked up again while growth slowed, and the gap between r and g widened, only to be moderated somewhat by the Global Financial crisis. The recent decades of the widening gap between r and g have also seen increases in wealth inequality.” – bto: und waren nur mit der Verschuldung möglich!

- “As shown in Figures 15 and 13, the returns to aggregate wealth, and to risky assets have remained relatively stable over recent decades. But the stock of these assets has, on the contrary, increased sharply since the 1970s, (…) The fact that this increase in the stock of wealth has not led to substantially lower returns suggests that the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour may be high, at least when looked at from a long-run macro-historical perspective.” – bto: Das ist meines Erachtens eben nur dank der gleichzeitig erfolgten Zusatzverschuldung möglich.

Quelle: NBER Working Paper 24112

- “Real house prices have experienced a dramatic increase in the past 40 years, coinciding with the rapid expansion of mortgage lending. (…) Measured as a ratio to GDP, rental income has been growing, (…). However, the rental yield has declined slightly — given the substantial increase in house prices—so that total returns on housing have remained pretty stable.” – bto: Und ich finde, diesen eindeutigen Zusammenhang sollte man zum Gegenstand der Politik machen, statt über höhere Einkommenssteuern nachzudenken. Es ist eben nur eine Folge unseres Schuld-Geldsystems.

Und hier der Link zur Studie:

-> w24112