Best-of bto 2019: Folgt Europa Japan in das deflationäre Szenario (III)?

Dieser Beitrag erschien im Juni 2019 bei bto:

Ich habe mich vor einigen Wochen intensiv mit einer Studie der Deutschen Bank zu den Parallelen

→ Folgt Europa Japan in das deflationäre Szenario (I)?

und zu den Unterschieden

→ Folgt Europa Japan in das deflationäre Szenario (II)?

zwischen Europa und Japan beschäftigt. Heute nun der dritte und letzte Teil der Studie der Bank, der versucht, zu einem Ergebnis zu kommen:

Zunächst die Zusammenfassung der Lehren der ersten beiden Paper:

- “(…) we have compared and contrasted Europe post 2008/09 with Japan post 1990. (…) Back then, globalisation was accelerating, multilateral organisations were thriving, and the global labour supply (ex-Japan) was growing quickly. This was positive for global growth and disinflationary. Japan’s failure to normalise inflation was due not only to an inadequate policy response to the bursting of the credit bubble but also to the global disinflation environment.” – bto: Japan hatte aber nicht nur Gegenwind mit dem deflationären Druck, sondern auch Rückenwind durch offene Märkte und eine recht gute Weltkonjunktur.

- “(…) Europe’s response to its ‘turning point’ recession was more proactive. (…) A combination of a shrinking global workforce outlook, less globalisation, and more populism could lead to higher inflation in the future than Japan experienced post 1990. Fewer workers may mean more wage pricing power, and populism may reinforce this by increasingly directing policy (e.g. fiscal) towards those ‘left behind’. Also, while we live in a fiat currency era, money printing can always be used to finance this if there is political will. Inflation is a political choice that may become more attractive globally as the years of lower growth and high debt progress. So ultra-low inflation need not be inevitable despite bad demographics.” – bto: Das stimmt und vermutlich brauchen wir den großen inflationären Schub, um die Probleme irgendwie aus der Welt zu schaffen. Die Frage bleibt halt, ob es erst zur Deflation kommt oder nicht.

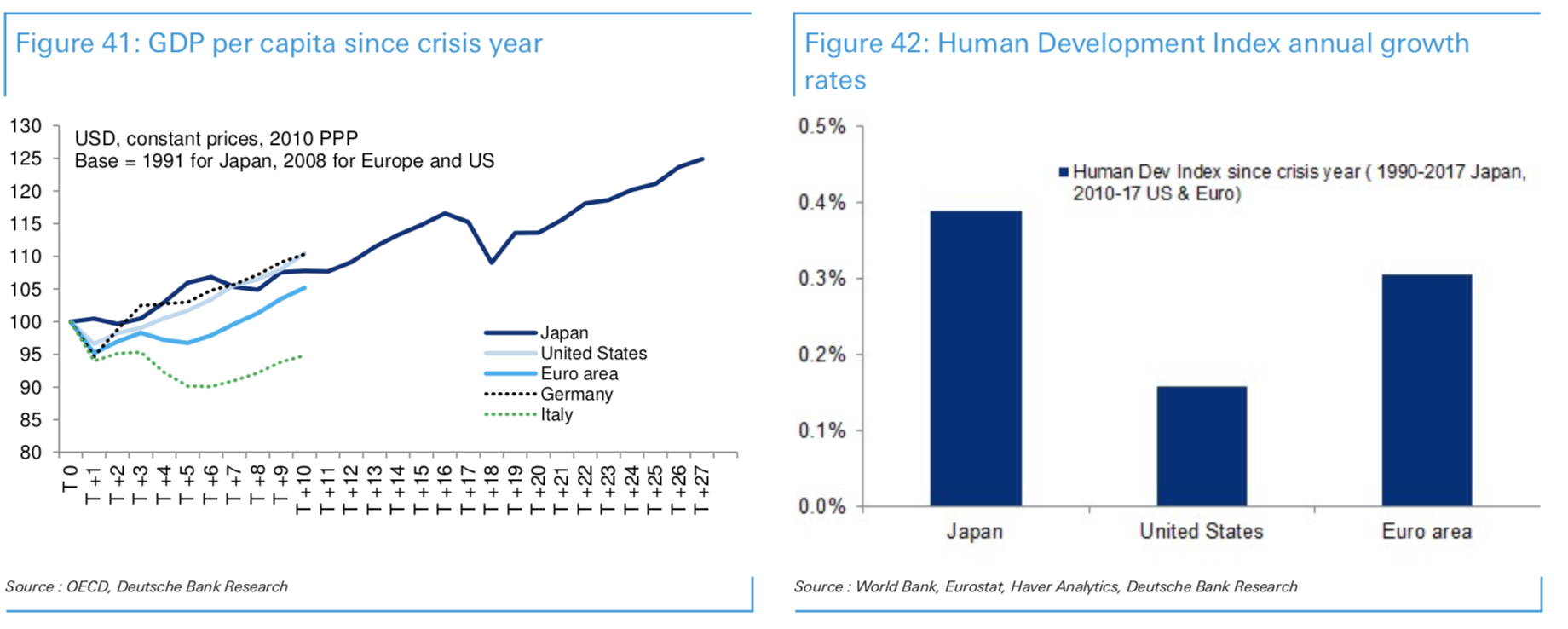

- Dann geht die Bank auf einen Punkt ein, auf den ich auch immer wieder Hinweise: “An interesting angle we consider is that on many measures (e.g. GDP per capita, human development, education, living standards, income inequality), Japan has actually had a good outcome over the last 25-30 years. Europe would be pleased to have 1% annual productivity growth!” – bto: So ist es und es wird bei uns noch viel schlimmer, wie immer wieder gezeigt! Bildung, Innovation und Investition mit Zuwanderung in das Sozialsystem sind Garanten für einen Niedergang.

- “(…) Europe remains highly vulnerable. The heterogeneity across its member states and the lack of political, fiscal and banking union mean that divergences are not internalised as they are in other large economies.” – bto: Das springt mir dediziert zu kurz. Ich denke, es hat mit den anderen genannten Punkten zu tun und widerspiegelt die Misswirtschaft auf unserem Kontinent. Hinzu kommen die Heterogenität der Bevölkerungen und die geringere Leidensbereitschaft. Das kann man nicht durch noch mehr Umverteilung heilen. Ohnehin nicht, weil derjenige, der zahlen soll, selbst sterbenskrank ist.

- “Unfortunately, a Japan-like scenario of long-term persistent low nominal GDP growth is thus not a sustainable equilibrium for Europe. (…) weak economies like Italy would be threatened by perennial stagnation or worse. At a member-state level, it is Italy that most resembles Japan. Its public debt problem is perhaps the greatest threat to the sustainability of the single currency area. (…) Despite its travails, Japan at least had the benefit of strong global growth. Not only is Europe more export-sensitive than Japan, but also globalisation is under threat, (…) and China’s economic model is under increasing scrutiny. Indeed, we argue that China has more striking parallels with Japan than Europe does. (…) Add to this the headwinds for global growth from global depopulation, retreating globalisation and perhaps lower global productivity, and Europe’s heavily export-oriented economic model feels like an increasing risk to stability and sustainability.” – bto: Und Albert Edwards würde sagen, dass wir in Wirklichkeit alle auf dem Weg nach Japan sind, auch die USA.

Die Bank fasst dann kurz die Ergebnisse der anderen Paper zusammen, dazu empfehle ich meine beiden Stücke dazu, siehe Links oben. Um dann zu sagen, was im Fokus des letzten Teils ist:

- “Demographics – Although demographics are very similar, with a 20-year lag, the global demographics are very different now than they were in the 1990s, when Japan first faced its problems. This may lead to different global policies than those seen starting in the 1990s.” – bto: und zwar – so vermutlich die These – zu mehr inflationärer Politik.

- “Geopolitics – Globalisation and mainstream global politics were the order of the day when Japan initially encountered its problems. Today, the former is in danger of reversing, and the latter is at the mercy of populism. In addition, European politics is becoming fragmented and the region currently has a lack of economic homegenity that might not even allow for a Japan-like outcome if faced with similar issues.” – bto: Genau, so ist es!

- “China and Italy more like Japan than Europe? As a curveball, on some measures China looks more like Japan. Within Europe, Italy looks worse than Japan did, highlighting the lack of economic homogenity.” – bto: Ein Deutschland mit wegfallendem Export und sterbenden Industrien sieht schneller aus wie Japan, als die Deutsche Bank sich denkt.

- “Would Japan actually be a good outcome? – 8 (…) On many measures, Japan looks like a healthy and balanced society and economy. Could Europe possibly reach such a scenario?” – bto: Ich bezweifle es angesichts der dysfunktionalen Führung hier.

Doch nun zu den einzelnen Punkten:

Demografie

- “Outside of an unlikely turnaround in the EU’s immigration policies, it is quite clear that Europe will face depopulation, and without a near equally unlikely radical overhaul of retirement ages, they’ll also face falls in the number of workers. As a minimum, this will constrain the potential rate of real GDP growth in the continent to very low levels relative to the past. Structural reforms and a global productivity rebound will likely be needed to improve this from what will be a population-constrained low level. In this respect, real growth will have similarities to that seen in Japan.” – bto: bekannt und unumstößlich.

- “Given the poor demographic outlook, the common perception is that there is an inevitability that inflation will also follow the same path. (…) with Europe about to depopulate, it will suffer the same battle against deflation that Japan has faced over the last 20-plus years.” – bto: Das macht die vorhandene Verschuldung untragbar.

- ABER: Es könnte auch anders kommen – und wie ich schon mal gezeigt habe, halte ich das für wahrscheinlicher: “(…) in theory it’s easy to create inflation if there is political will, regardless of lower population growth. High global debt and populism may be the catalyst in the future. If central banks were to print a substantial amount of money and give it to the population (via governments), that would create inflation. So, if the global challenges are different in the future than those in 1990s Japan, then the political will and preferences could be different.” – bto: und “should be”. Helikopter und MMT kommen doch nicht ohne Grund in die Diskussion!

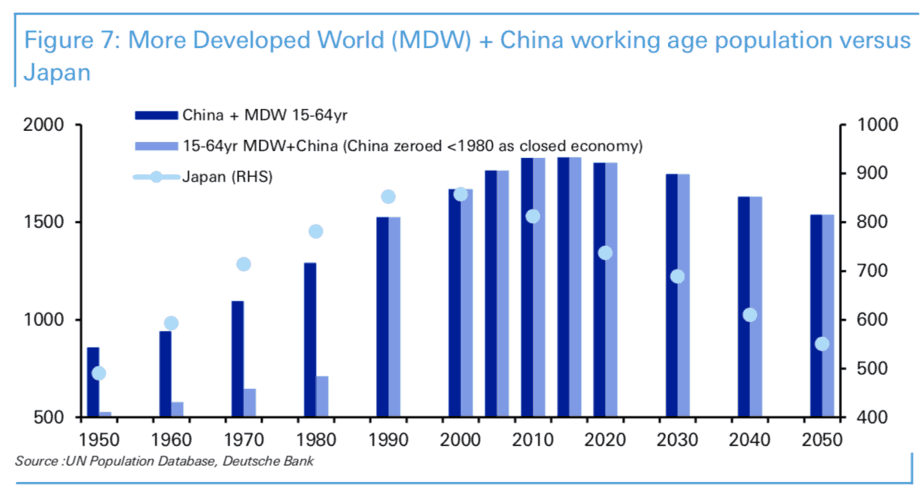

- “Figure 7 shows the working-age population in the More Developed World (MDW) plus China over the last 70 years and that expected over the next 30 years. In the light of the two bars, we have zeroed China before 1980, as prior to the late 1970s the Chinese economy was effectively closed to the outside world. China then decided to integrate itself into the global economy and over the last 35-plus years has effectively dropped over a billion cheap workers onto the global economy at a time when baby boomers in the West were already naturally helping to dramatically boost the global labour market size. Thus, labour costs – and with them a big part of inflation – have likely been exogenously controlled by this surge in the global labour force since 1980.” – bto: Und das ist auch der Grund, warum meine Krisenbefürchtungen alle falsch waren. Es gab einfach einen enormen externen Schock, den ich mir nicht vorstellen konnte.

- “(…) labour will likely regain some pricing power in the years ahead as the supply of it now plateaus and then starts to slowly fall. Any economic growth should therefore see upward pressures on labour costs, all other things being equal. (…) Indeed, if ‘bad’ future demographics are so negative for inflation, why has inflation been on such a 35- to 40-year downward trend when demographics have been so good?” – bto: Wie ich schrieb, sollten vor allem nicht handelbare Güter wie Dienstleistungen im Preis steigen, global skalierbare Dinge hingegen weiter billiger werden. Gut möglich, dass die Klimadiskussion eigentlich eine versteckte Protektionismus- und Re-Regionalisierung-Politik ist.

Globalisierung und Geopolitik

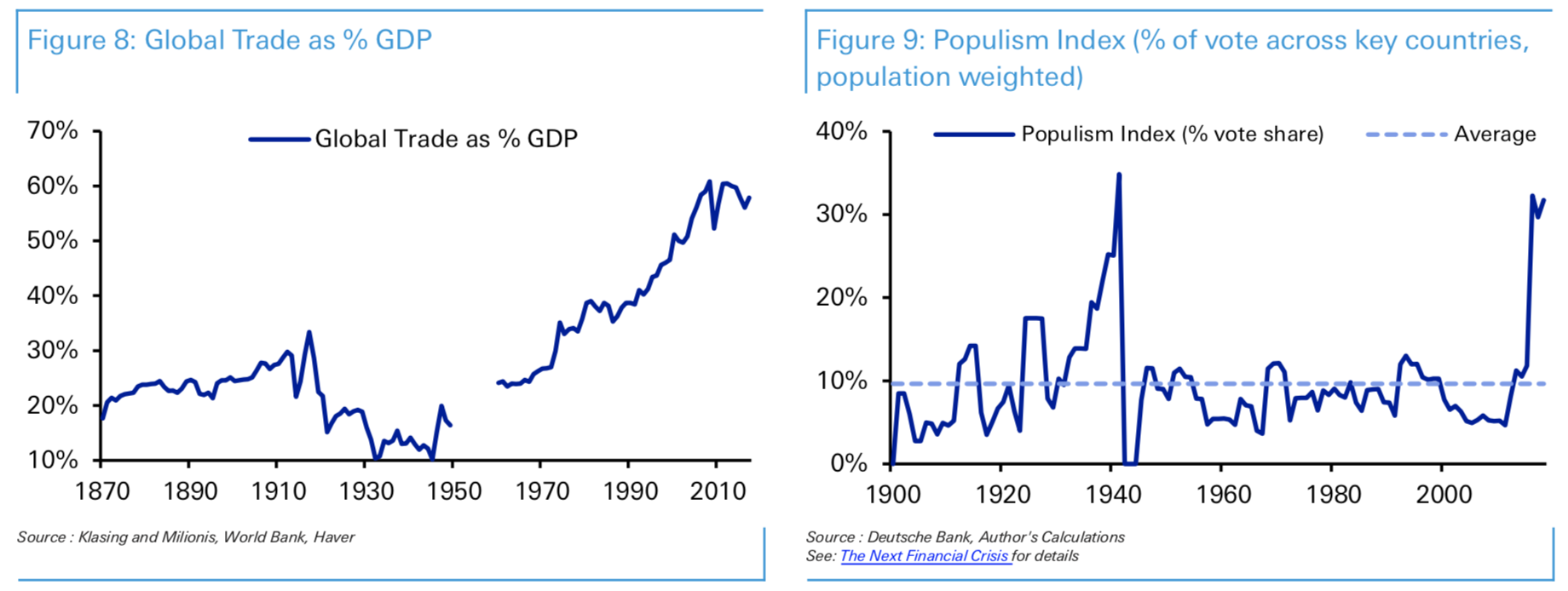

- “Figure 8 shows that global trade as a percentage of GDP (…) has leveled off over the last few years, and there are increasing signs from across the globe that globalisation is under threat as the political order changes. The most obvious example is the current trade dispute between the US and China. (…) Multilateral organisations that policed this benign world order, and which Europe relies upon, are also becoming less influential.” – bto: Und der Klimaschutz wird auch dazu missbraucht.

- “Related to this, populism is increasingly taking over from the generally mainstream/ centrist politics of the 1990s and 2000s. Figure 9 shows the rise of populism for seven of the most important economies of the world since 1900 and illustrates that it is as high as at any point in modern history outside the 1930s.” – bto: Auch das ist eine Entwicklung, die im Zusammenhang mit der bereits bestehenden Abkühlung der Wirtschaft steht.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “The risks to globalisation could mean higher inflation as barriers to trade increase, pushing prices and costs up. Rising populism could also mean more fiscal spending as politicians appreciate that to gain (or stay in) power they need to spend on the poorer half of their population – generally those left behind by the globalisation era and those now rebelling against it. This higher fiscal spending at a global level is likely to lead to a more reflationary era than that seen over the last 35-40 years.” – bto: Der Wunsch besteht auf jeden Fall, aber ob es realisierbar ist!

- “(…) given the lack of regional homogeneity in Europe, by definition ultra-low nominal growth would mean divergence across nations. Without a fully functioning political and fiscal union, it seems inevitable that such a Japan-like economic environment from here would lead to an economic crisis and/or more serious political upheaval within a few more years. (…) economic and political crises far more likely to arise in the years ahead than occurred in Japan.” – bto: Davon bin ich auch überzeugt.

China eher mit Japan vergleichbar

- “(…) Europe is excessively dependent on global growth and arguably has too much savings rather than too much debt. A common remedy would be a shift in fiscal policy to (a) reduce excess savings, (b) support domestic demand and (c) (hopefully) increase potential growth. In the absence of a fiscal union, such a policy would need to be determined at the country level – in Germany in particular.” – bto: was bekanntlich in unserem eigenen Interesse wäre!

- “So far, Germany has demonstrated little appetite for a proactive fiscal policy. To some extent, this is because its cyclical position is not dire enough to justi – fy a countercyclical fiscal stimulus.”

Und jetzt zu den Parallelen zwischen Japan und China:

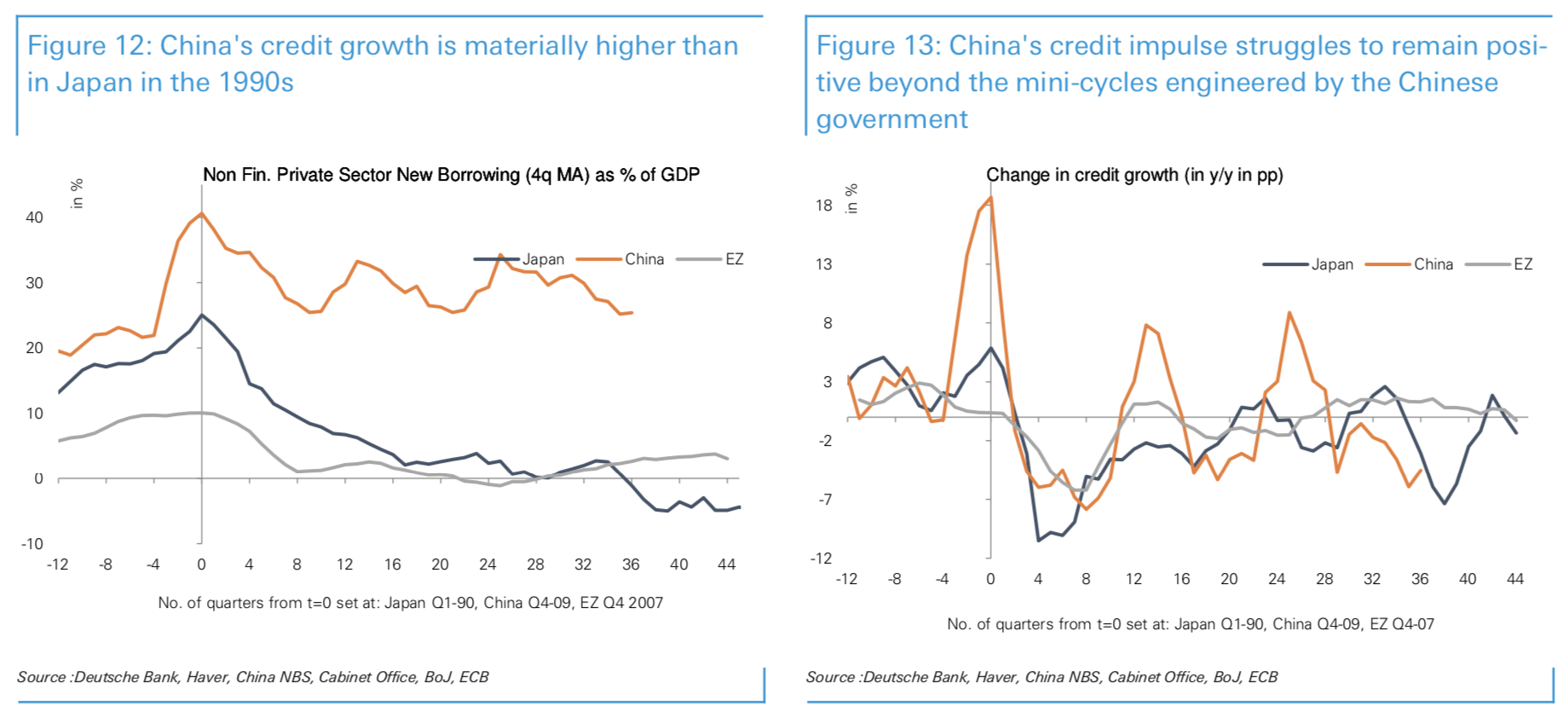

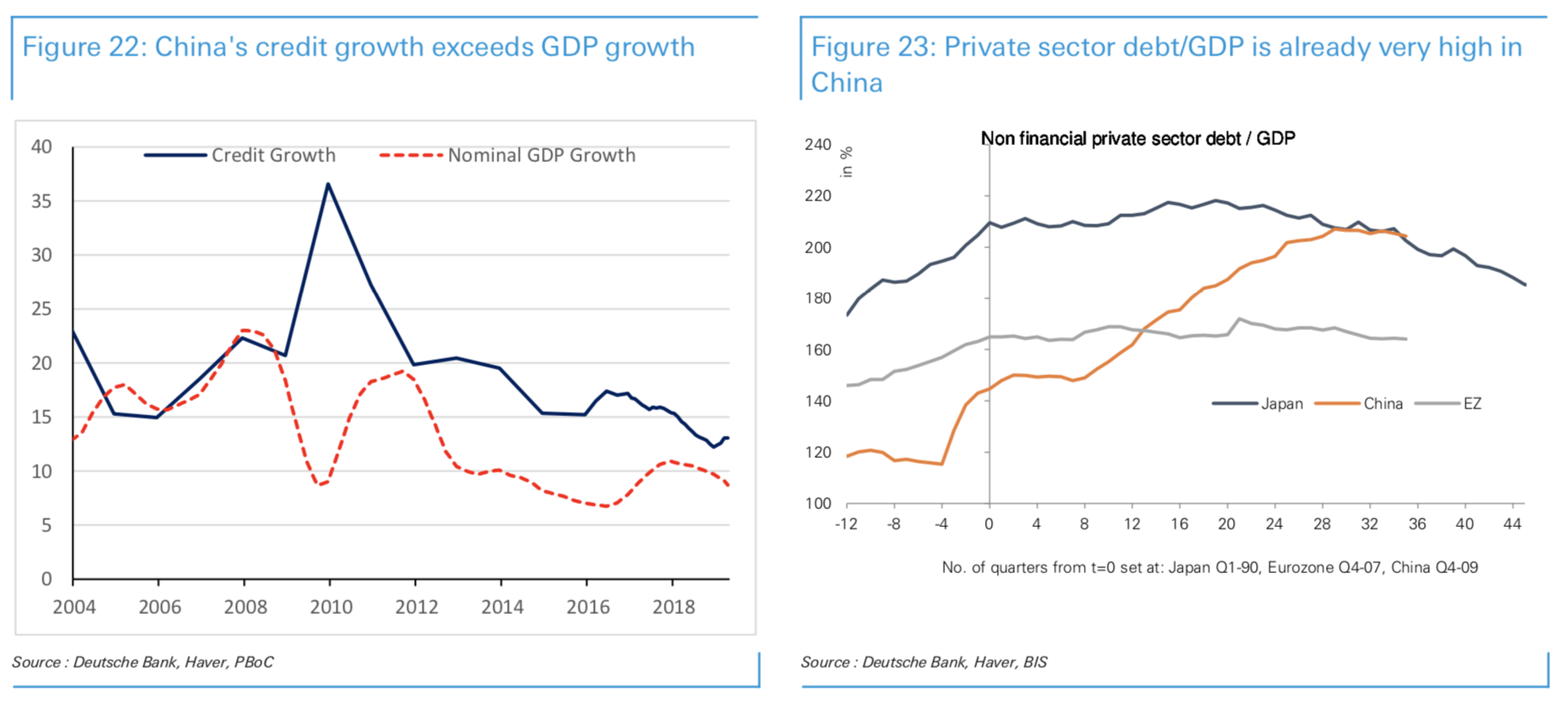

- “To assess if China has some Japanese features, we analyse the evolution of key variables in event time, setting as a reference date (t=0) the peak in credit growth (Q1-90 for Japan and Q4-09 for China). First, we focus on the dynamics of credit growth. (…) China has a significant credit overhang, which has so far not been convincingly resorbed. Indeed, credit growth in China increased from ~20% pre-crisis to ~30% post-crisis and is materially higher than in Japan in the 1990s (left graph below). The excessive credit growth is preventing a sustainable improvement in the credit impulse beyond the mini-cycles engineered by the Chinese government (right graph below).” – bto: Ich erinnere an → China: Schuldenwirtschaft nach westlichem Vorbild

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

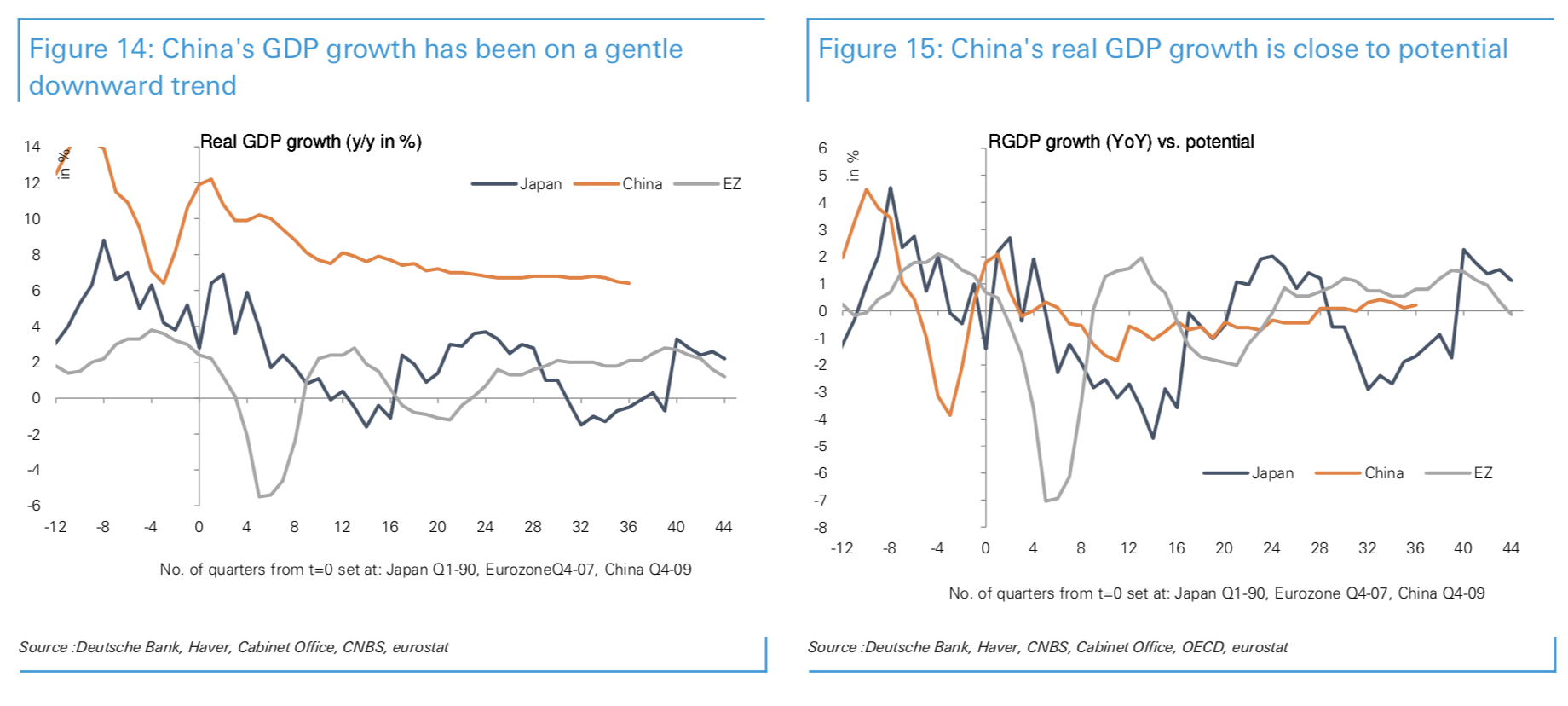

- “The excessive credit creation has resulted in investments in unproductive sectors of the economy, leading to a decline in potential growth. As a result, despite its decline, GDP growth has remained close to estimates of potential (right graph below).” – bto: Das ist die Folge der Zombifizierung. Und da holen wir bekanntlich schnell auf.

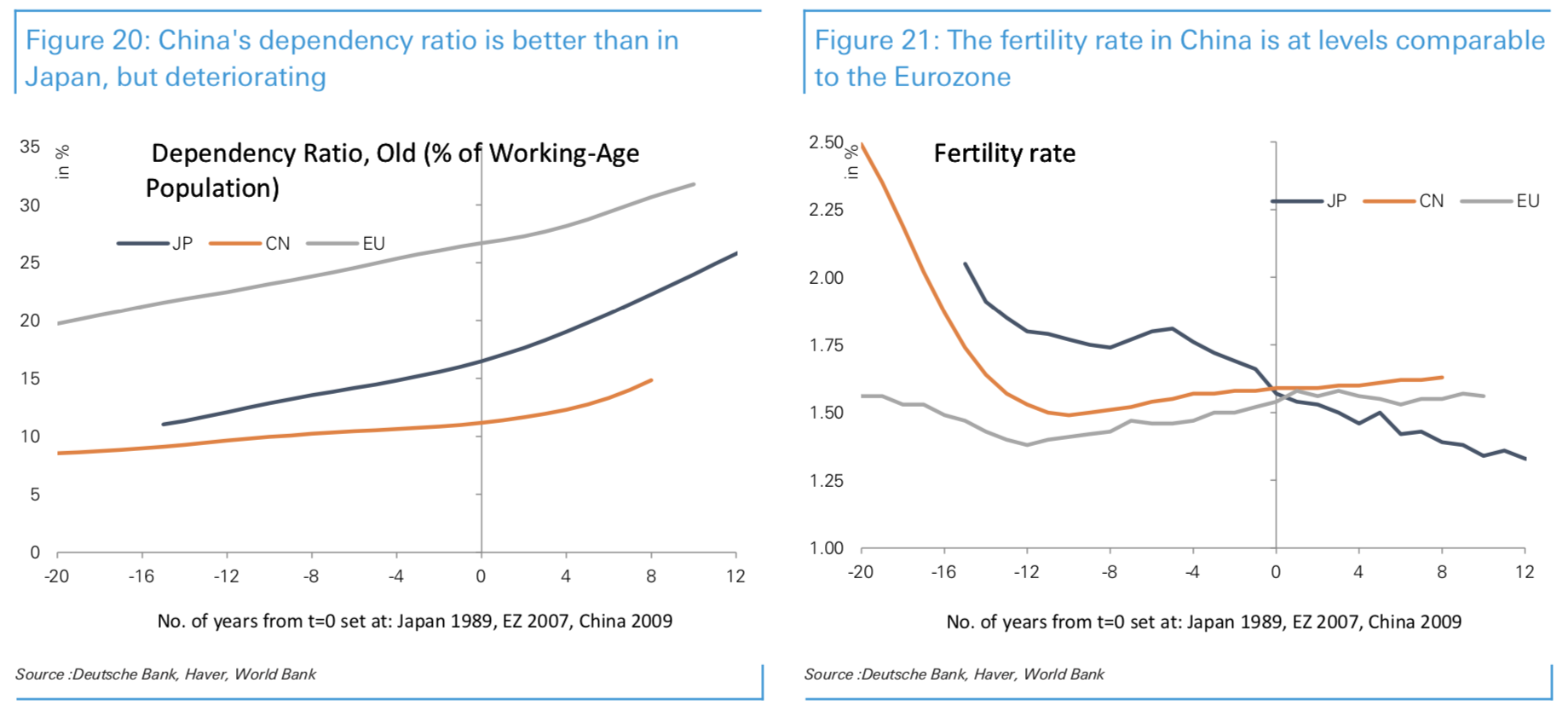

- “The demographics in China are better than in Japan at the time, but still on a deterio- rating trend. The dependency ratio is ~5% lower than it was in Japan (left graph below) but is on an upward trend. Pre-crisis, the fertility rate had already declined to levels comparable to Japan on the back of the one-child policy. It has recovered slightly (while in Japan it deteriorated further) and is at levels comparable to the Eurozone.” – bto: China wird alt, bevor es reich wird.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “(…) one key feature could put China on a Japanese trajectory: the size of its credit bubble. Ultimately, credit growth will need to decline back to levels in line with nominal GDP growth (~8%) from current levels of closer to 15% (left graph below) to avoid having its total-debt-to-GDP on a continued upward trajectory (right graph below). As long as this adjustment has not occurred, the risk of a Japan-type outcome will remain. Given Europe’s exposure to global trade and to China, how this plays out is crucial to the continent.” – bto: Wir hängen an dem chinesischen Kreditzyklus. Keine guten Aussichten! Die Verschuldung des Landes ist viel zu hoch und genauso wie wir im Westen braucht das Land eine Lösung für das Problem.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

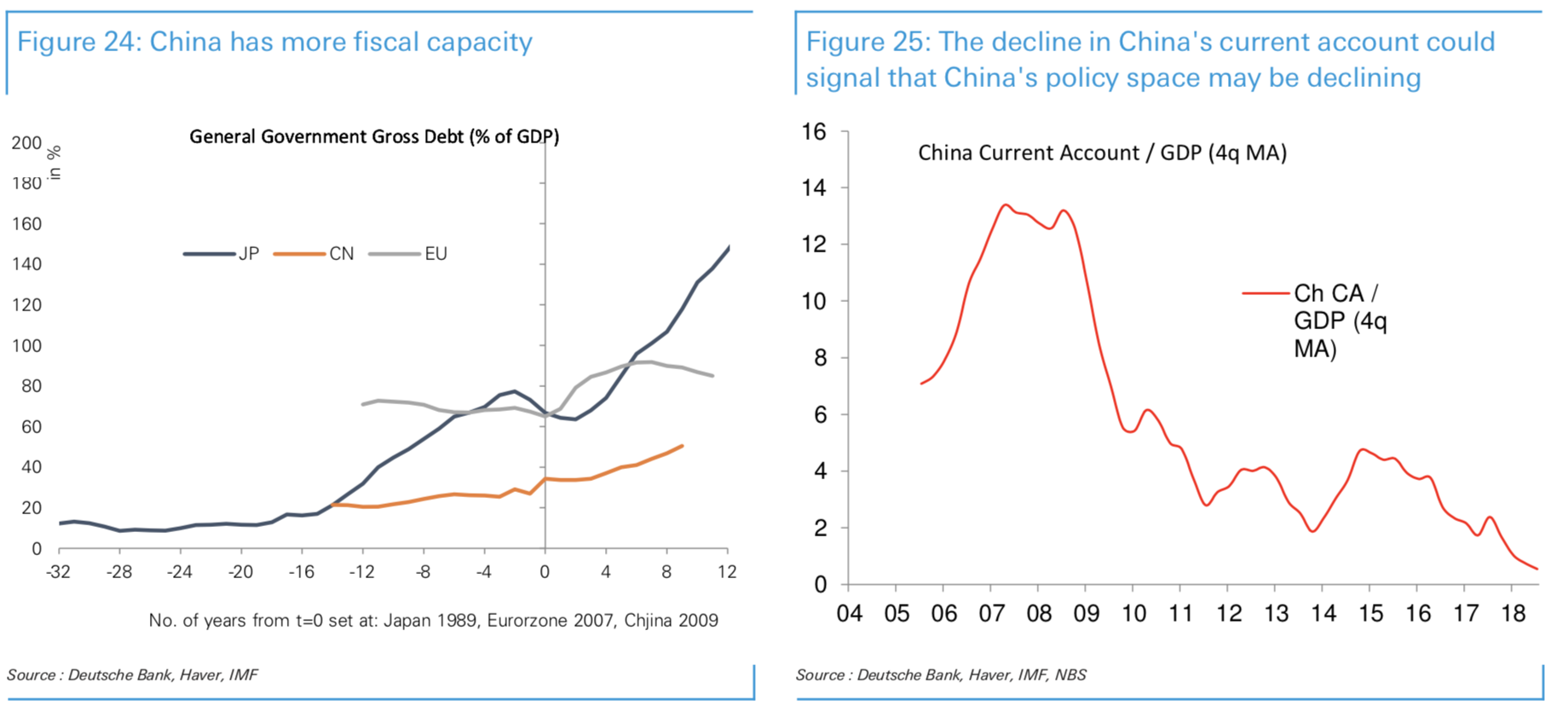

- “On the positive side, China is a ‘command and control’ economy with a lower public-sector debt- to-GDP (left graph below). This provides some capacity to manage the inevitable deleveraging. However, the decline in the current account position suggests that the policy space is becoming more constrained (right graph below).” – bto: Und da grätscht nun der Handelskrieg hinein.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

Italien als schwächstes Glied

Italien ist bekanntlich schon lange in einer Krise gefangen. Ich denke, mit Blick auf die Verschuldung steht Frankreich nicht besser da und Deutschland ist genauso krank wie Italien, merkt es aber noch nicht. Unser Märchen endet mit der Rezession und dem tödlichen Wandel unserer Industrie. Dann kann zwar der Staat mehr Schulden machen, doch das ändert nichts an den Problemen. Doch nun zu Italien:

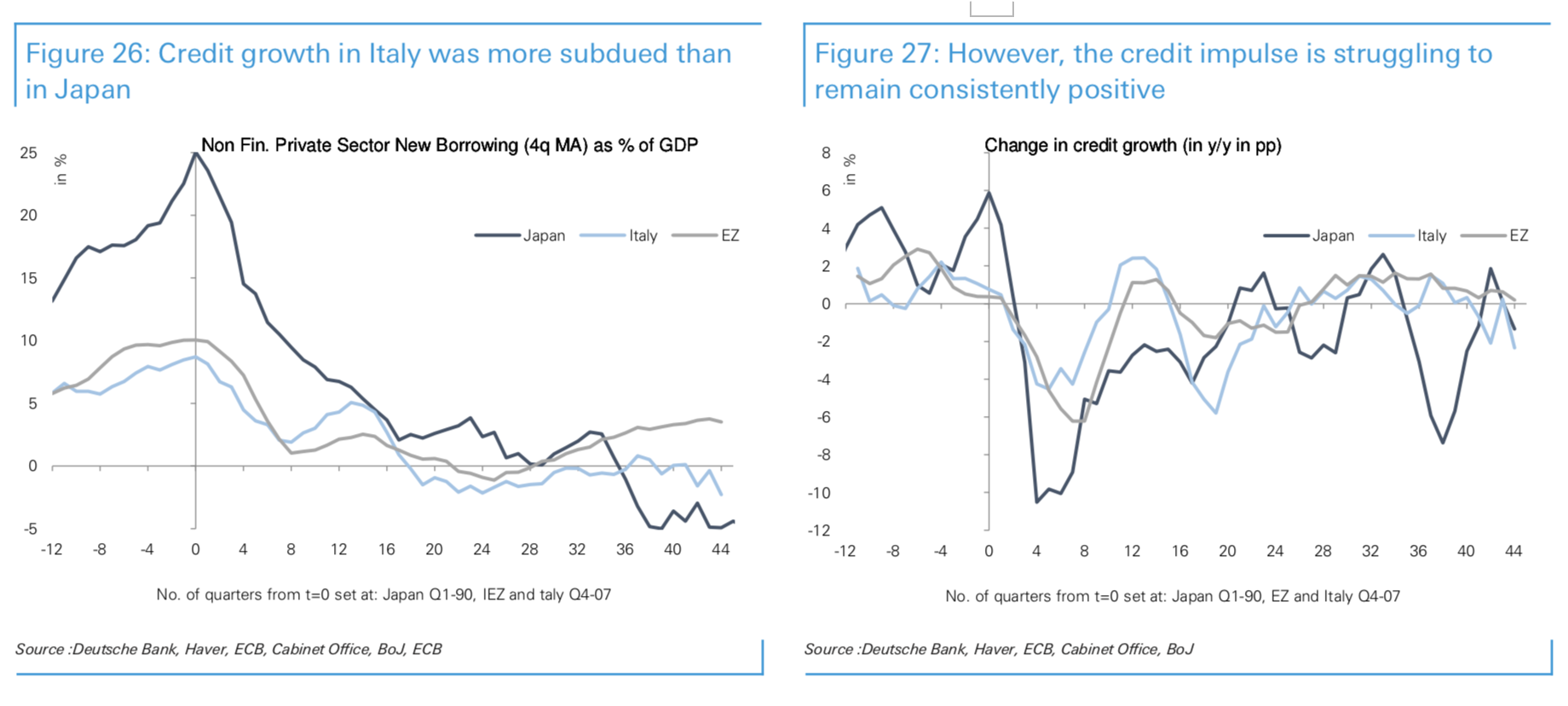

- “Italy did not witness a very large credit bubble, and in that respect it does not resemble Japan too closely (left graph below). However, even if private-sector credit excesses were relatively limited, the credit impulse struggled to turn meaningfully positive (right graph below).” – bto. Das muss man nämlich immer wieder sagen. Die privaten Haushalte im Land sind vermögend.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “Italy did manage to grow above potential for a few years and reduce its unemployment gap. However, the process of resorbing excess capacity has stalled, and monetary and fiscal policies may not be as accommodative as necessary. Demographics in Italy are worse than in Japan at the time. This leaves Italy dangerously close to the Japanese experience but perhaps without some of the benefits we discuss in the final section below. On the positive side, Italy shares some of the strengths of Japan as it has a relatively robust external position. Its current account is positive and its NIIP (adjusted for Target II) is also slightly positive.” – bto: weshalb es ja auch so attraktiv für das Land wäre, den Euro zu verlassen.

Wäre das japanische Szenario so schlecht?

Meine Antwort ist klar: Nein, es wäre ein super Ergebnis, das Europa aber nicht schaffen kann. Gründe sind bekannt.

- “The conventional wisdom surrounding Japan over the last 2-3 decades has been that it’s faced a gloomy and negative experience. Nominal GDP growth stagnated, public debt levels exploded, and policy appeared impotent. The experience has been acutely painful for investors in certain asset classes. (…) the Japanese stock market sold off over 60% between 1989 and 1991, and it has still not recovered to those levels again some 30 years later.(…) Bank stocks, which are highly cyclical and can be used as a proxy for the impact of persistently low rates, have performed even more poorly. On a total-return basis, an index of bank stocks languishes at around 10% of its peak value. Banks have been suffocated by slow growth, depressed inflation, and persistently low nominal interest rates.” – bto: und deshalb Finger weg von Bankaktien!

- “(…) Japan has been able to generate real GDP growth of ~1% thanks to productivity growth. This resulted in a relatively strong real GDP per capita performance for a country emerging from such a large (private) debt crisis. Productivity growth has remained robust.(…) in the long run, only productivity growth results in rising living standards.” – bto: Nach dem Chart sieht es bei uns in Deutschland noch recht gut aus. Ich denke aber, dies liegt an der Sonderkonjunktur, die den Rückgang des Produktivitätswachstums kaschiert, siehe die Ausführungen dazu vor ein paar Wochen.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

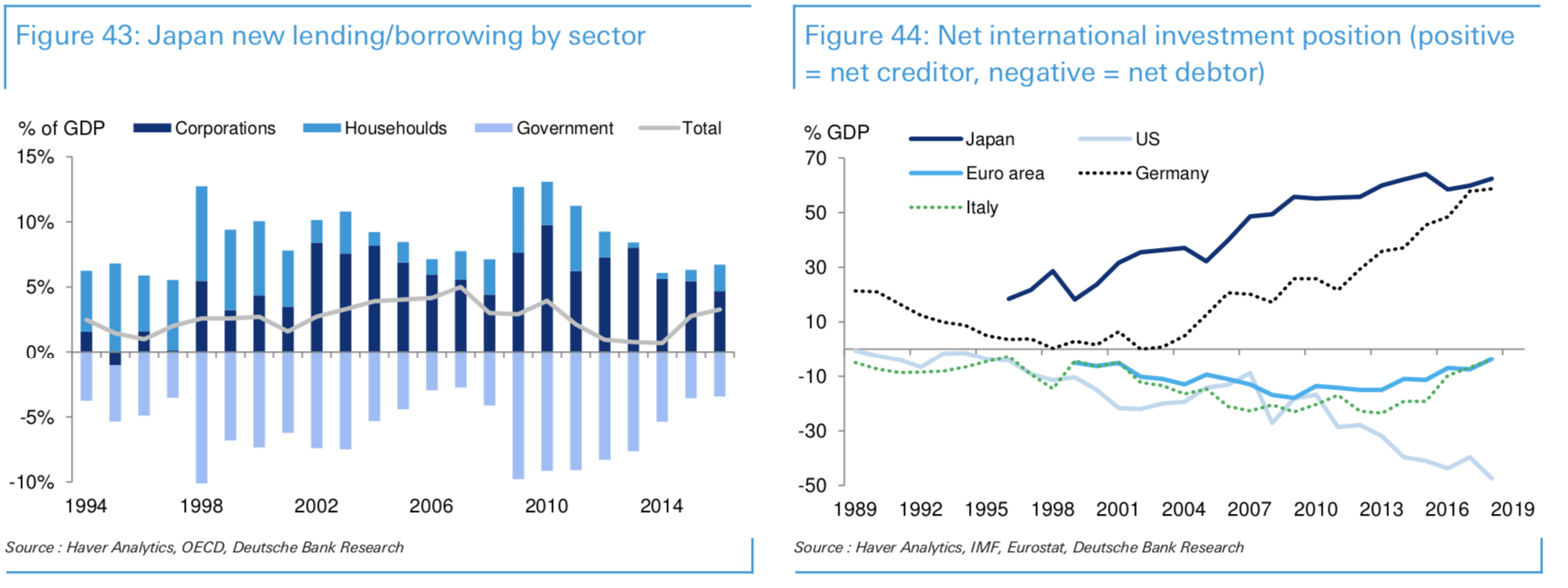

- “Contrary to popular belief, this rise in living standards did not come at the expense of large overall indebtedness. The rising public debt was accompanied by large private savings from corporates (and households); this led to increasing net savings, with Japan being one of the largest creditors in the world, as reflected by its net international investment position. While the public sector in Japan undoubtedly is a huge driver of dissavings, the chart below shows how this was more than out-weighed by the private sector.” – bto: Und die Japaner sparen besser im Ausland als wir!

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

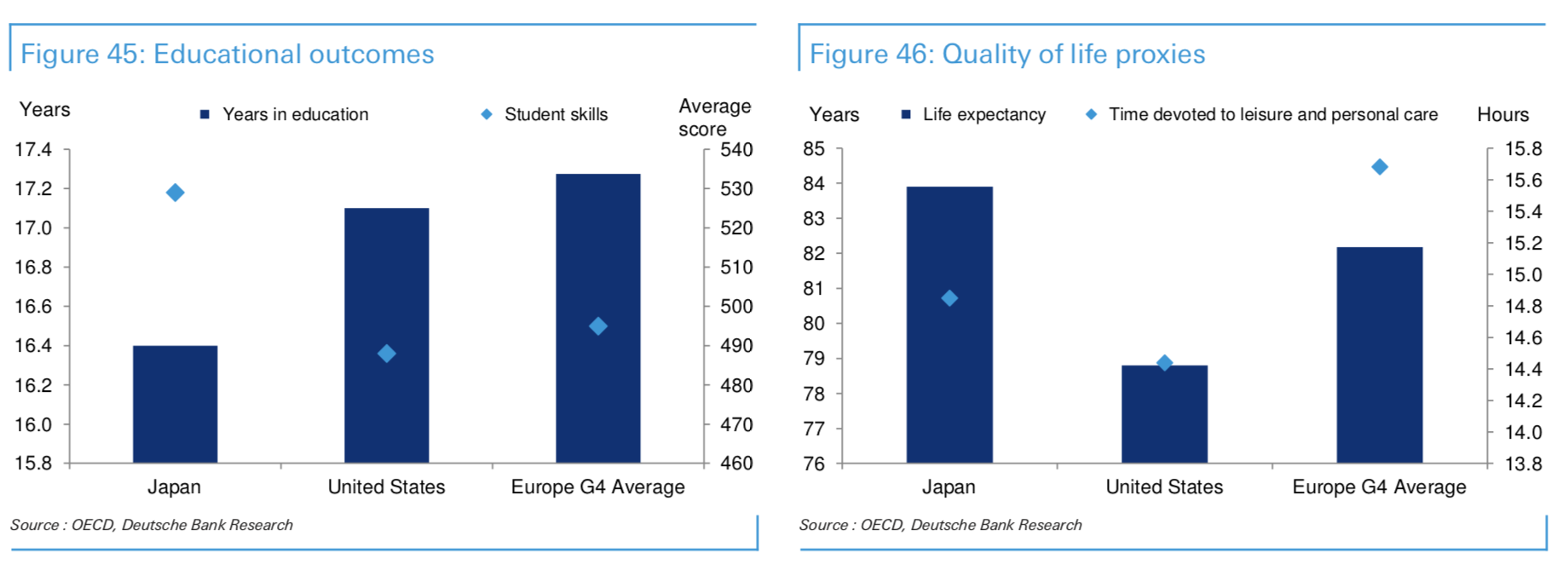

- “By international standards, the Japanese seem to have developed an efficient public education system. While they spend fewer years at school than peers in other developed nations, the teaching they receive leads to better skills, as reflected by the OECD Pisa scores. (…). Beyond human capital considerations, the Japanese population seems to enjoy healthy lives with enough time for leisure.” – bto: Ich denke, das hat auch kulturelle Gründe und eine allgemeine Lernorientierung. Die Leistungen in Mathematik sind herausragend, ebenso die Innovationskraft der Wirtschaft. Hier befinden wir uns abgeschlagen weit hinten und allein mit mehr Geld wird man das nicht heilen können. Wir brauchen eine Leistungskultur statt dem Geist der Elitenfeindlichkeit.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

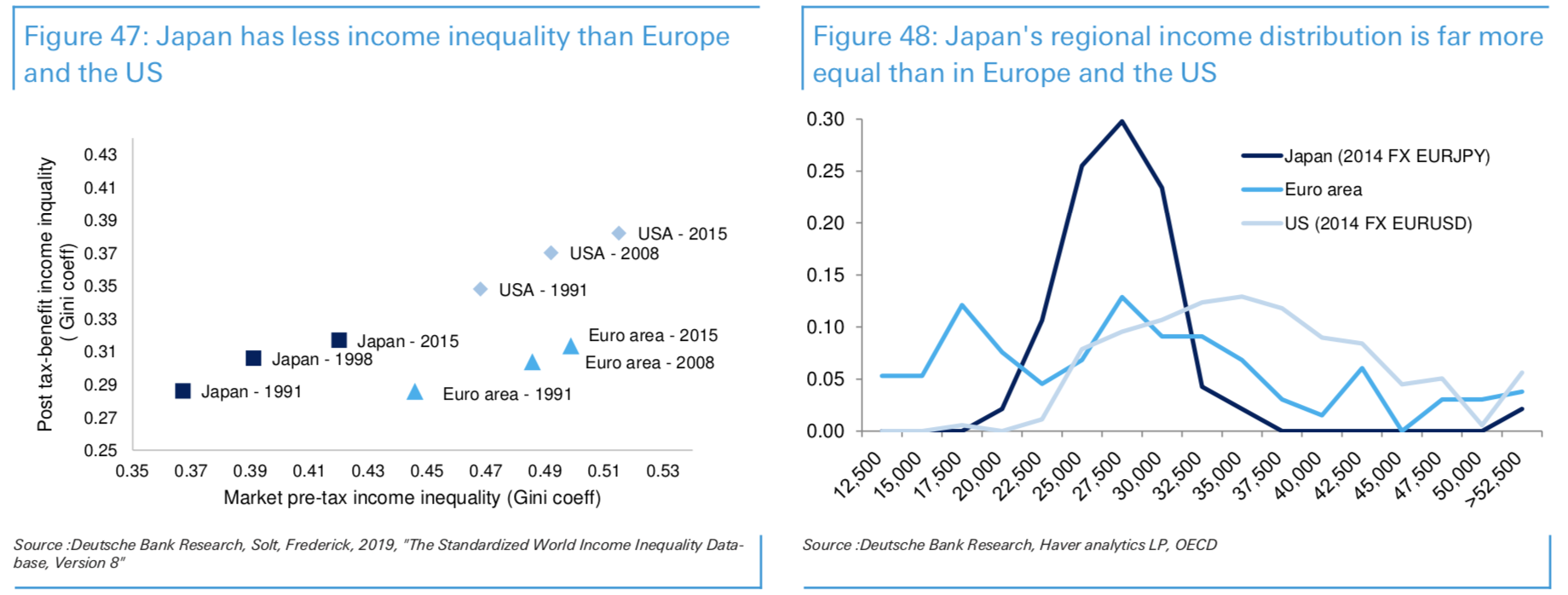

- “Japan (…) has managed to maintain impressively low levels of income equality. Figure 47, reports the Gini coefficient for pre- and post-tax house-hold income inequality at various points in time. Japan appears to achieve post-tax inequality levels of a typical Euro-area country with a much lower pre-tax level of inequality. This suggests that the need for redistribution is more limited there.” – bto: was mit der Bildung zusammenhängen dürfte!! Aber auf die Idee kommt ja niemand bei uns. Stattdessen lieber mehr Umverteilung.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “(…) the level of development in Japan is far less heterogeneous than in the US or the Euro-area. Figure 48 reports the distribution of GDP per capita of small regions in each economic area. While the levels of inequality between Japan and a typical Euro country are comparable, the heterogeneity across countries in the Euro-area leads to a large dispersion of GDP per capita in Europe.” – bto: was natürlich wieder nichts anderes bedeutet, als dass wir mehr umverteilen müssen. Scherz! Wir müssten an den Ursachen ansetzen … und das wäre mühsam und unpopulär.

Fazit: Wir sind nicht wie Japan, sondern deutlich schlimmer dran. China hat wie Japan eine Bildungskultur und eine gesamtgesellschaftliche Leidensfähigkeit, von der wir nur träumen könnten. Damit ist klar, dass wir vor einem politischen und sozialen Sturm stehen, der Europa vermutlich dramatisch verändern wird. Leider nicht zum Besseren. Folge von jahrzehntelanger falscher Politik, die nun, so sieht es aus, beschleunigt fortgesetzt wird.