Folgt Europa Japan in das deflationäre Szenario (I)?

Es ist wieder zunehmend Thema der Diskussion: Inwiefern ähnelt die Entwicklung in Europa, und zwar konkret die der Eurozone, jener in Japan? Zeitversetzt steuert der Euroraum in das eigene Szenario geringen Wachstums, deflationären Drucks und ungebremster Verschuldung.

Diese Diskussion ist vor allem deshalb so wichtig, weil es einen entscheidenden Unterschied gibt. Die Eurozone ist kein homogenes Land, sondern besteht aus verschiedenen Ländern mit unterschiedlichen Kulturen und vor allem sehr unterschiedlicher Bereitschaft der Bürger, für ein übergeordnetes Ziel persönliche Einschnitte hinzunehmen. Man blicke nur auf Frankreich, wobei es bei uns nicht anders ist, kann man doch nur so die Politik der letzten Jahre erklären.

Doch wo stehen wir mit Blick auf das „japanische Szenario“? Nun, nach einigen Studien bleiben wir fest auf Kurs. So zitierte die FINACIAL TIMES (FT) letzte Woche eine Studie der BNP Paribas, die doch glatt einen „Japanisation index“ erarbeitet hat. Der zeigt in die falsche Richtung:

Allerdings gibt sich die Bank noch optimistisch: “The eurozone’s current inflation outlookis better than Japan’s was in the early 1990s, and its labour market structures are less likely than Japan’s to allow wage growth to slow sharply.” – bto: wobei man da sagen könnte, dass dies in Deutschland bisher nicht immer gestimmt hat.

Bleibt das Problem, dass der EZB nicht mehr viele Mittel bleiben und die Inflationsrate schon recht tief liegt. Deshalb: “When a negative shock hits, the eurozone is likely to adjust ‘downwards’, towards lower eurozone-wide demand, lower inflation and lower interest rates — closer to a Japanese-style trap.” – bto: So ist es. Wobei ich skeptisch bleibe, dass man überhaupt mit Interventionen etwas gegen die Japanisierung tun könnte, auch dann nicht, wenn man der Empfehlung der BNP folgt (was man wird): “The dosage of the different medicines must change, away from excessive reliance on monetary policy and towards more fiscal and structural policies. But that gets us back to eurozone reform.” – bto: Der Zug dürfte abgefahren sein, weil wir schon seit zehn Jahren über Nebenkriegsschauplätze diskutieren.

Weit ausführlicher setzen sich Analysten der Deutschen Bank mit dem Thema auseinander. „How Europe is looking like the next Japan“ lautet der Titel der Anfang April erschienenen Studie, deren Kernaussagen ich hier kurz zusammenfassen möchte. Im ersten Teil der Studie geht es um die Gemeinsamkeiten zwischen Japan und der Eurozone, im zweiten Teil um die Unterschiede. Beginnen wir mit den Gemeinsamkeiten, Teil zwei kommt heute Nachmittag:

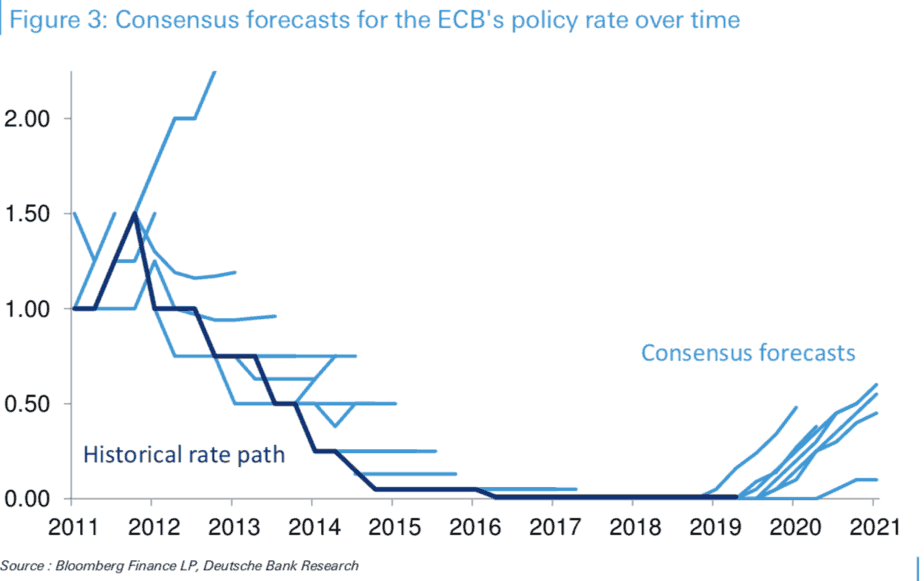

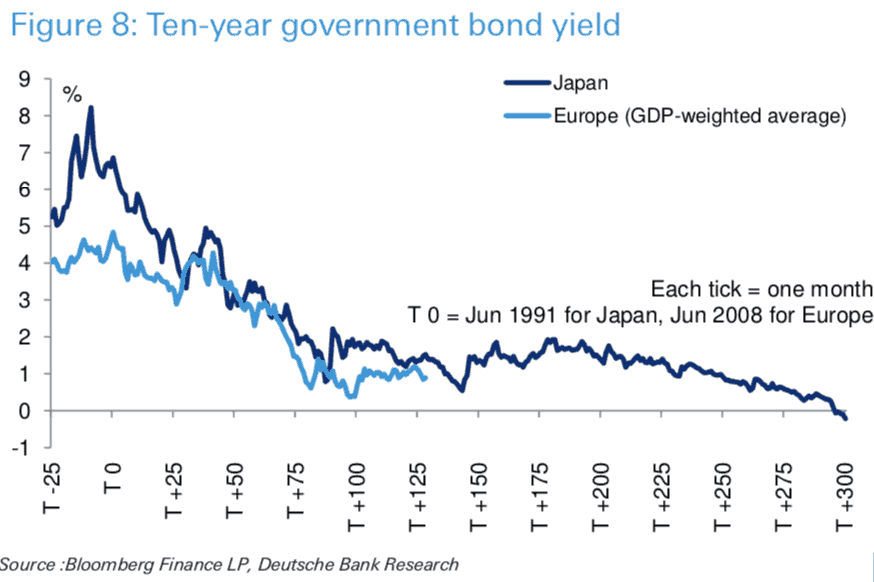

- „In February this year, the Bank of Japan celebrated an ominous anniversary: 20 years since it first cut interest rates to zero. Despite a few abortive attempts to raise policy rates, they have never again exceeded 1% and remain stubbornly stuck around zero. Likewise, Europe has seen a few false dawns but again looks set for a long period of short-term rates being stuck at or below zero. (…) As such there are ever-growing similarities between the Europe of today and the Japan of the past two to three decades.” – bto: was sicherlich stimmt. Allerdings kommt in der Eurozone die Besonderheit hinzu, dass die Währung nur bei Null-Zins existieren kann. In Japan ist es kein Problem der Währung. Dazu zeigt die Bank dann den Zinsverlauf der beiden Regionen zeitversetzt, also passend zum Beginn des jeweiligen Niedergangs:

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

Und dann ein weiteres Bild, was zeigt, dass die Analysten die Natur der Krise der Eurozone scheinbar nicht wahrhaben wollen. Denn intellektuell dürften sie sie sehr gut verstehen …

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “As a starting point for the comparisons it’s tough to look past demographics. (…) It can affect the quantity of national savings, the level of investment demand, the rate of potential economic growth, inflation, and many other macro variables. When demographic trends are unfavourable, they end up increasing aggregate savings while simultaneously reducing investment demand. Aging populations naturally tend to save more, as a greater share of the population prepares for retirement, which results in higher national savings. At the same time, as more of the population ages out of the workforce, the overall labour supply shrinks. This results in lower potential growth rates, which depress the need and demand for investment spending.” – bto: Das ist alles bekannt. Interessant ist, dass es scheinbar keine höhere Inflation bei nicht handelbaren Gütern gibt, denn dort sollte sich die Knappheit der Arbeitskräfte niederschlagen.

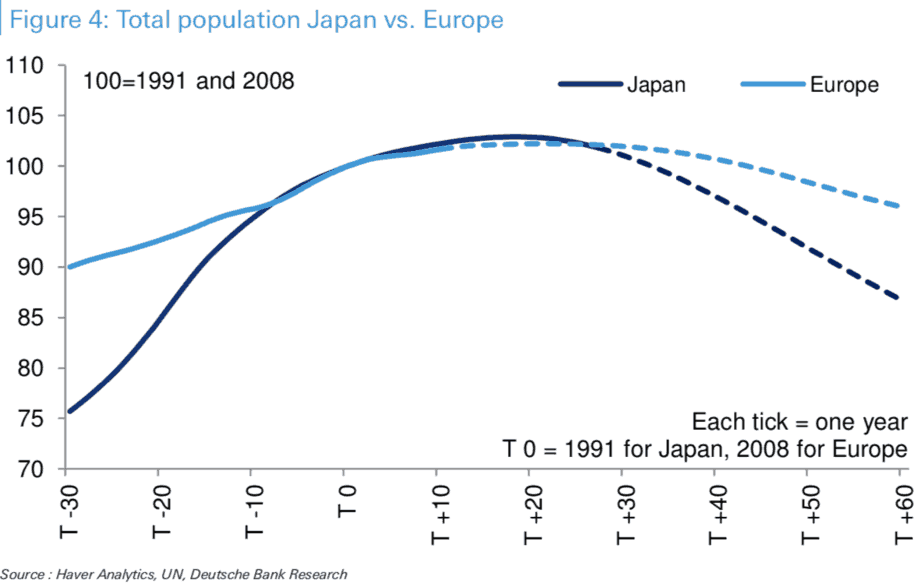

- “Figure 4 shows the total population of Japan and the euro area, indexed to their ‘turning point’ levels. For Japan, (the) UN forecasts (…) an annual rate of population growth of -0.5% over the next 27 years, or a -12% total decline. In Europe (…) the predicted path over the next 20 years looks very like Japan over the past 20 years. Interestingly, Japan is now at a point where the recent, mild depopulation is about to accelerate. Fortunately for Europe, this acceleration isn’t likely to be as bad in the more distant future, however its the next 20 years that’s worryingly similar to Japan.” – bto: Jetzt muss man natürlich wissen, dass es gerade in Deutschland besonders schlimm ist, während Länder wie Frankreich (und übrigens auch UK) weiter wachsen. Da aber die Eurozone an Deutschland hängt, ist das keine gute Nachricht.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

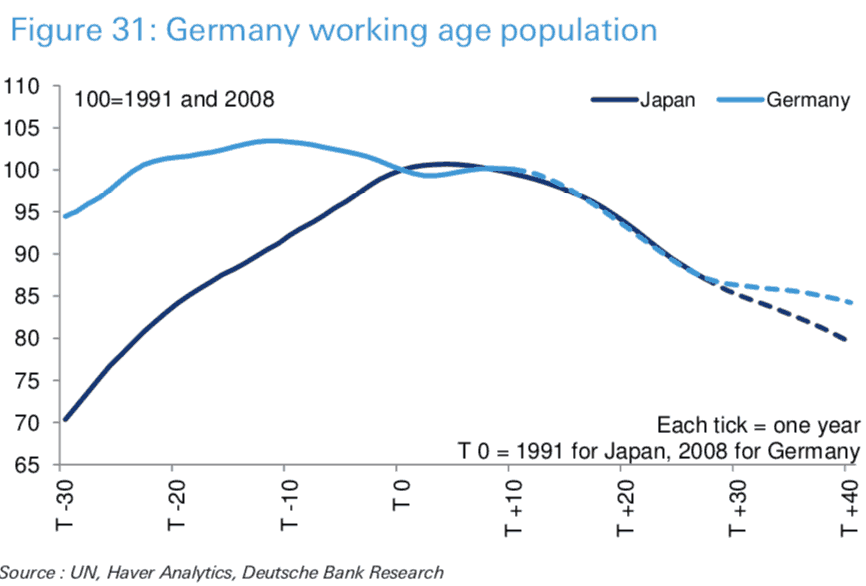

- “Even more important is the working age population, defined as people aged 15-64 years old. (…) In Japan, the working age population has already declined over 12% since 1991, an annual pace of -0.5%, and the trend is forecast to accelerate in the near future. Over the next 30 years, the UN forecasts Japan’s working age population to decline at an annual rate of -1.0%, a 25% overall decline through 2048. In Europe, the working age population (…) has evolved in a similar direction and is expected to continue to decline at a similar pace. Over the next 30 years the working age population in Europe is forecast to decline -15%, an annual pace of -0.5%. This is basically the same trajectory that Japan has been on in recent years.” – bto: Und besonders schlimm sieht es unter anderem in dem Backstop für das ganze Projekt aus. Deshalb auch gleich als nächste Abbildung die Lage in Deutschland, die nun wirklich japanisch wirkt!

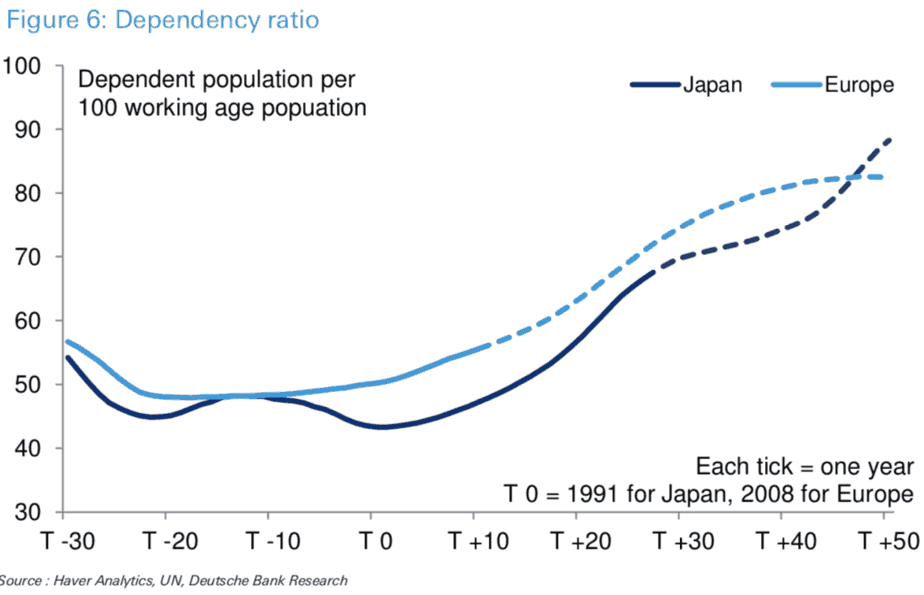

- “Another popular metric of demographics is the dependency ratio, which shows the number of people aged less than 15 or over 65 per 100 working age population (i.e. aged between 15 and 65). As more of the population shifts from working age to dependent age, investment opportunities dry up and savings increase. In both Japan and the euro area, the dependency ratio troughed right around the start of their ‘turning point’ recessions. As can be seen Europe over the next 20 years looks similar to Japan of the last 20 years on this measure.” – bto: Und weil es so schön ist gleich auch noch Deutschland dazu. Das Ganze widerspiegelt die Dramatik, beginnen wir den Prozess doch schon auf einer schlechteren Ausgangslage!

Sodann geht es um die Zinsen: “In Europe and Japan, markets priced-in a return to normalcy immediately after their “turning point” recession, and subsequently experienced some notable ‘false dawns.’ In 2011 and over the last couple of years of more decent growth, the market positioned for ECB interest rate hikes. In Japan, these moves ended up being premature and market pricing now reflects close to zero expectation of any imminent rate moves. So rightly or wrongly the rates market seems to price in a Japan like outcome over the years ahead.” – bto: in der Eurozone – wie gesagt – verstärkt durch die Notwendigkeit, die Währung am Leben zu erhalten.

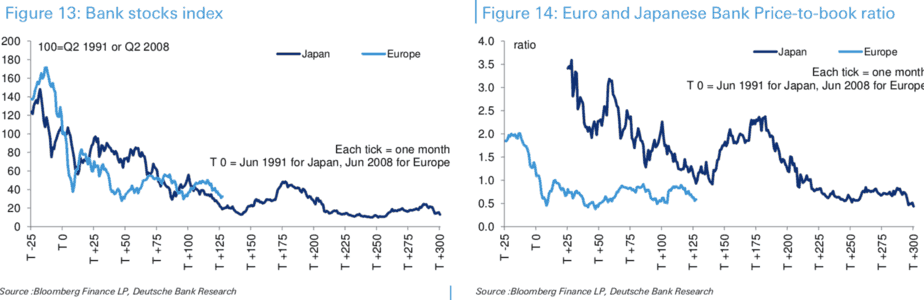

Dann kommt unweigerlich der Vergleich der Bankensysteme, beide unsaniert und insolvent: “The very low level of interest rates in both economies has also weighed on their respective banks. European bank stocks have so far tracked their Japanese equivalents with the same 17-year lag as we’ve used throughout this piece and price-to-book ratios are actually well in advance of the Japanese trend.” – bto: Das liegt natürlich nicht nur an den Zinsen, sondern an den vielen faulen Krediten, die vergeben wurden und ist deshalb problematisch, weil in beiden Regionen die Banken eine entscheidende Rolle bei der Finanzierung spielen.

Dabei zeigt die Erfahrung, dass es der Geldpolitik nicht gelingen muss, die gewünschte Inflation zu erzeugen: „The Japanese experience proves that it is possible to keep monetary policy ultra-loose for decades and still fail to stimulate inflation while the health of the banking system deteriorates. The window to raise policy rates to address bank profitability has seemingly closed and the continent’s banks are at dire risk of being permanently weakened. The failure to achieve ‘escape velocity’ in Japan, and the staunch adherence to low rates, is a key reason why Japanese banks fail to cover their cost of equity.“ – bto: Und genau dasselbe passiert hier in Europa.

Danach nutzt die Bank die Ergebnisse der Studie zum europäischen Bankensystem, die wir hier schon hatten:

Und fasst entsprechend zusammen: “Given the situation in Europe increasingly mirrors that in Japan, it is no wonder that the share prices of European banks trade at just over half their book value, closer to Japanese valuations (well ahead of the 17-year cycle lag), while US banks trade over their book value. Of course, US banks have received a boost from nine interest rate hikes in the current cycle. In fact, since the cyclical low of three per cent in 2015, US bank net interest margins have improved to 3.5 per cent supported by the Fed rate cycle. This has fed the divergence in valuations between European and US banks since that time.” – bto: Die US-Banken verdienen rund 40 Milliarden mit ihren Anlagen bei der Fed. Auch das hilft natürlich.

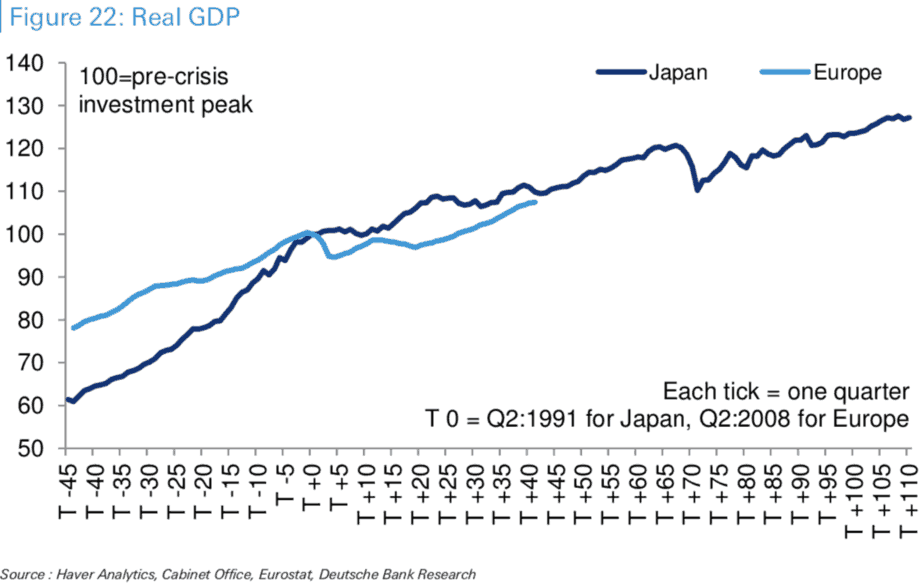

Kein Wunder, dass es mit Blick auf die Realwirtschaft schon jetzt schlechter aussieht in der Eurozone als in Japan! „(…) in terms of real GDP growth, the euro area is actually performing worse than Japan did in the 1990s. Of course, the global financial crisis and subsequent recession was a much more severe global event, but it is still remarkable that Europe’s real GDP has stagnated more than Japan’s when you use the 17-year lag.” – bto: Nein, ist es nicht. Wir haben es zu tun mit verschiedenen Ländern, die schon vor der Krise mit Blick auf Produktivität und Innovationsfähigkeit weit hinter Japan lagen! Wir könnten uns glücklich schätzen, wenn es uns so gut erginge wie Japan, aber das wird es nicht.

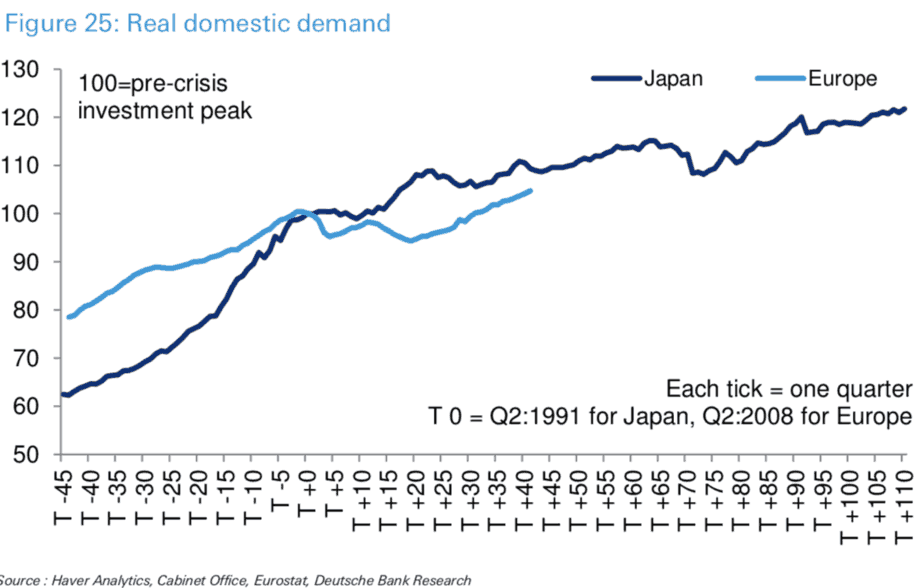

Danach zeigen die Analysten, dass vor allem die private Konsumnachfrage zurückbleibt in Europa, während es bei den Investitionen etwas besser aussieht als in Japan. Das kann man damit erklären, dass es bei uns eine Schuldenkrise vor allem der privaten Haushalte war und in Japan eine der Unternehmen. (Ja, in Spanien waren es auch Baufirmen etc., aber im Schnitt sind es vor allem private Haushalte und Staaten, die betroffen sind). In Summe liegt die Entwicklung der Nachfrage schon jetzt unter der von Japan: “Taken together, and adding in similarly tepid spending via the fiscal channel, we see that European real domestic demand is quite weak. It is only 5% above its 2008 level, growing at a similar pace as Japan did in the 1990s and 2000s. This is characteristic of chronically deficient domestic demand.” – bto: Das unterstreicht das erhebliche Problem der ungelösten Euro-Frage.

- “Given Europe’s deficient domestic demand, it may seem puzzling that its growth has held up even as well as it has. The answer is a strong performance of net exports, with real net exports more than doubling from their 2008 level. This is notably better than Japan, and accordingly suggests that domestic demand is even weaker in Europe than it has been in Japan. Can Europe’s economy continue to be export led in a world of slower Chinese growth and risks to globalisation though?” – bto: hey. Ja, alle haben sich verbessert, aber es ist doch wohl eine deutsche Geschichte mit Industrien aus dem Kaiserreich … Außerdem kann die Eurozone nicht zu einem großen Deutschland werden. Dann wird nicht nur Trump ungemütlich!

Fazit dieses ersten Teiles der Studie der Deutschen Bank: “(…) both are textbook cases of secular stagnation with a chronic lack of demandand a surplus of savings chasing too-few investment opportunities. With such a gap, and interest rates constrained by the zero lower bound, it becomes difficult for monetary policy to gain traction and boost the economy. This results in deficient domestic demand and persistent ultra low growth. These conditions apply to both Japan in the 1990s and Europe today. Accordingly, Europe is in real danger of becoming ‘the next Japan’ and, barring policy changes, the dangers will increase.” – bto: Die vielen Aspekte, wo Europa deutlich schlechter dasteht als Japan, wurden gar nicht erwähnt. Ich verweise nur auf den Kommentar von Gunnar Heinsohn zum Beitrag vom letzten Montag (29. April).

Heute Nachmittag schauen wir auf den Versuch, uns Hoffnung zu machen!

Die Studie kann ich leider nicht verlinken.