“The consequences of Italy’s increasing dependence on domestic debt-holders”

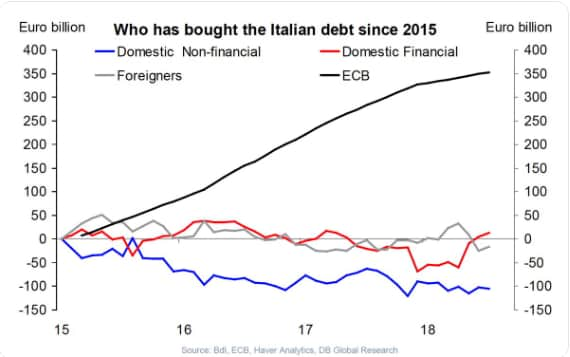

In einem meiner Beiträge zur italienischen Schuldenkrise habe ich geschrieben, dass es der italienischen Regierung darum geht, die Kosten eines Schuldenschnittes ins Ausland zu verlagern. Nicht wenige Leser kamen daraufhin mit der richtigen Feststellung, dass doch ein wesentlicher Teil der Schulden von Inländern gehalten würde und ich deshalb falsch liegen würde. Deshalb zur Klarstellung: Jeder Schuldenschnitt sollte aus italienischer Sicht so ablaufen, dass ein möglichst großer Teil des Schadens bei Nicht-Inländern eintritt. Da hilft zum einen, dass die EZB die einzige Käuferin in den letzten Jahren war:

Dazu gehört aber auch, eine Sozialisierung der Kosten einer etwaigen Bankenrettung, nachdem diese entsprechende Verluste mit Anleihen realisiert haben. Auf jeden Fall führt der Druck der Italiener bereits zum Einknicken auf Seiten der Rettungseuropäer, die nun fordern, über den ESM eine Zinssubventionierung zu erreichen, indem der Rettungsmechanismus Anleihen aufkauft, die er „im Falle einer fehlenden Verbesserung der Lage in Italien“ abschreibt. So der Vorschlag des Chefvolkswirts der Deutschen Bank und an dieser Stelle bereits gewürdigt:

→ Die Provinzen sollen zahlen – und schon wird es empfohlen!

Derweil halten sich die Auguren noch an der Tatsache fest, dass Italien derzeit ja immer mehr von einheimischer Finanzierung abhängt und diskutieren die Konsequenzen, so auch der Think Tank Bruegel:

- “The substantial increase in the proportion of Italian bonds held by the Bank of Italy since 2015 (from 5.8% to 19.3% of total outstanding debt) is an operational consequence of the quantitative easinglaunched by the European Central Bank, and is common across euro-zone countries. Beside this monetary policy-driven change, however, the portion of remaining bonds held by residents (banks and other investors combined) relative to non-residents has kept increasing since the last observation.” – bto: Nun kann man ja noch niemanden zwingen, italienische Anleihen zu nicht risikoadäquaten Zinsen zu kaufen.

- “(…) around 2005, sovereign bonds of France, Germany, Italy and Spain were each held by foreigners at a very similar level (in the neighbourhood of 50%). Since then, foreigners have owned an increasingly small share of Italian debt, in particular after the 2011-12 crisis, falling below 35% of the total outstanding debt.” – bto: was nichts anderes zeigt, als dass der Markt halt doch noch teilweise funktioniert.

- “According to Jalles (2018) and Afonso and Silva (2015), the share of sovereign debt held by non-residents increases due to several factors, such as (i) improved fiscal positions, (ii) a strong business cycle position, (iii) systemic stressand financial volatility, and (iv) a higher share of cross-border holdings of sovereign bonds by foreign monetary and financial institutions (MFI).” – bto: Man könnte auch einfach sagen, alles was die Kreditwürdigkeit stärkt, führt zu mehr Nachfrage, alles was sie schwächt, zu weniger.

- “None of these variables point to an inversion in the trendof Italian debt ownership, given (i) the planned increase of the deficit (in terms of GDP) in the Italian draft budget, (ii) the generalised economic slowdown that characterised the third quarter of 2018 in the euro zone (which translated into downright stagnation in Italy, which registered 0% quarter-on-quarter growth for the first time after 14 quarters of positive, if dismal, growth) (iii) the Italy-specific, and not systemic, stress and financial volatilityobserved up to now and (iv) foreign banks’ exposure to Italian debt amounting today to less than half the levelit reached in 2008.” – bto: Das ändert nichts daran, dass gerade die französischen Banken ganz vorne mit dabei sind und wie im Falle Griechenlands darauf hoffen, von deutschen Steuerzahlern gerettet zu werden.

- “(…) the geographical composition of a sovereign’s creditors matters because of the relationship between these creditors and a government’s (i) borrowing costs, (ii) refinancing risks and (iii) financial stability altogether, through the establishment or reinforcement of the linkage between the sovereign and resident banks.”– bto: Allerdings ist es was anderes, wenn die Risiken der Banken im Rahmen der Bankenunion von anderen getragen werden.

- “(…) foreign investors are a less stable sourceof demand for sovereign bonds. In this respect, Italy’s public finances might prove more resilientthan the size of its debt and political developments would suggest – also given the more-than seven-year average maturity of its outstanding bonds (higher than the German and American maturity, for instance).” – bto: Das stärkt auch die Verhandlungsposition der Italiener mit Brüssel.

- “(…) research seems to suggest that fiscal multipliers are relatively lower when residents own a higher share of public debt (see Priftis and Zimic 2017 and Broner et al. 2018). The underlying theoretical intuition is that there is a greater tendency towards a crowding-outof the domestic private sector when a relatively higher portion of public debt is in residents’ hands, thereby hampering domestic consumption- or domestic investment-driven expansion. This hypothesis relies on the assumption that the presence of financial frictions might limit private residents from having full access to external financing.” – bto: Im Falle Italiens dürfte das weniger ein Problem sein, ist doch die Nachfrage schon lange sehr gedrückt.

- “A lower-than-forecasted multiplier would thus increase the likelihood of higher-than-expected debt and deficit figures, and therefore of a tightening of fiscal policy. Such an outcome is even more likely since the long-run multiplier of public investments in Italy, as shown by Alessio Terzi, is among the lowest in Europe.” – bto: Glaube ich, dass die Schulden schneller wachsen als die Wirtschaft? Natürlich! Glaube ich, dass es dann ein “tightening of fiscal policy” gibt? Natürlich nicht! Es werden dann weiter Schulden gemacht und von der EZB, dem ESM oder den italienischen Banken aufgekauft. Was sonst?

- So stellt Bruegel eine ziemlich theoretische Frage und gibt eine noch theoretischere Antwort: “What could happen then, if the government indeed had to revise its estimates downward and provide a rebalancing of its fiscal position(either through increased revenues or lower expenditure)? Several signals point to the usual suspects: Italian residents, and their still substantial private wealth. (…) Some form of so-called financial repression, i.e. a more or less gentle diversion of private funds towards public debt, is therefore on the table, as suggested by the Bundesbank economist Karsten Wendorff and explicitly assumed by Moody’s. The former advocates a national fund, financed through ‘solidarity bonds’ that Italian households would be forced to purchase according to a fixed proportion of their net wealth (say, 20% in order to halve total government debt). The latter similarly motivates its stable outlook despite the Italian debt rating downgrade: ‘Italian households have high wealth levels, an important buffer against future shocks and also a potentially substantial source of funding for the government.’” – bto: Warum sollte das eine italienische Regierung tun, solange es über Target2 eine weitgehend unbegrenzte Finanzierung gibt und schon über eine Rettung durch ESM und anschließende Abschreibung nachgedacht wird?

- “Such funding might alternatively occur through a substantial one-off property tax, the so-called patrimoniale. (…) In one way or another, however, the role of Italian resident investors in determining the fortunes of Italian debt does not seem set to diminish any time soon.” – bto: So argumentiere ich auch gerne. Sehe ich doch darin eine rationale Lösung für Überschuldungslagen. Andererseits muss man einfach anerkennen, dass Politiker immer versuchen werden, den Schaden für das eigene Land zu minimieren. Zumindest tun sie das in Italien.