Gedanken zur Sanierung des europäischen Bankensystems

Das europäische Bankensystem ist in keinem guten Zustand, allen Beteuerungen vom Gegenteil zum Trotz. Wie schlimm es aussieht, erkennt man alleine schon an den Aktienkursen. Weit von den Höchstständen entfernt, deutlich schlechter als die Wettbewerber in den USA. Gerade auch bei uns in Deutschland haben wir es mit einem Bankensystem zu tun, welches systematisch zu wenig verdient. Daran wird auch eine Fusion von Deutscher Bank und Commerzbank nichts ändern.

Dabei wäre ein gesundes Bankensystem ein wichtiger Baustein zur Überwindung der Krise in der Eurozone – ja, ich weiß, dazu gehört noch viel mehr! – und der Vermeidung eines japanischen Szenarios. Deshalb haben Analysten der Deutschen Bank einmal aufgeschrieben, was denn zu tun wäre, um die europäischen Banken zu sanieren. Interessante Lektüre:

- “The banking systems of Europe and Japan already exhibit a startling symmetry. First, households and corporates have a similar level of over-reliance on banks. Corporations in Europe and Japan tap banks for three-quarters of their financing requirements while the regions’ households rely on them for nine-tenths of funding needs. That is double and triple the proportion seen in the US, respectively.” – bto: wobei man sagen könnte, dass die geringere Ertragskraft der Banken in Deutschland den Kunden zu Gute kommt, und zwar genau den kleineren Unternehmen, die davon profitieren – im Unterschied zu den USA, wo der Nutzen des Kapitalmarktes nur die Großen begünstigt.

- “Yet although banks in Europe and Japan are leaned upon so heavily to support the real economy, falling returns leave them less able to support the sectors of the economy that need it the most. This is a serious problem, particularly as small and medium enterprises employ two-thirds of the European workforce, whereas equivalent US firms employ only about half the American workforce.” – bto: was natürlich stimmt. Nur wenn die Banken gesund genug sind, können sie dieser Aufgabe nachkommen.

- “‘(…) low profitability weakens a bank’s ability to accumulate capital‘ while drawing the connection between a sustainable business and the safety and soundness of the system. The increasing gap in profitability between European and US banks is a function of declining customer margins and, increasingly, the ECB’s ongoing negative rate environment. This has, in effect, imposed a tax worth about €8bn on the European banking industry (…) The theoretical opportunity cost of not being able to pass negative rates to household customers, based on overnight deposits, is €16bn, or five per cent of system net interest income and about ten per cent of pre-tax profit.” – bto: auch eine dieser negativen Nebenwirkungen der EZB-Politik!

- “The unintended consequence is that itacts as a fiscal transfer mechanism and redistributes cash from core Europe to the periphery. The periphery banking system is also the primary beneficiary of the €700bn TLTRO programme which can remunerate borrowing at 40 basis points.” – bto: unbeabsichtigt? Es ist Bestandteil des großen Rettungsprogramms, wo es auf allen Ebenen darum geht, eine Transferunion zu schaffen, ohne dies offiziell zu sagen.

- “Ultra-loose monetary policy is a good example of how European policymakers are copying the Japanese. While it is true that low rates mean lower provisions and higher capital gains, these effects are temporary while the compression of net interest margins is ongoing. Indeed, persistent low rates in Japan have led to net interest margins falling from 1.5 per cent in 2000 to 0.9 per cent now. In this regard, Europe is already heading down the Japanese path. While European banking margins have flat-lined at 1.65 per cent since the financial crisis, persistent low rates could significantly impact margins over time. Of course, lower margins can be good for an economy up to a certain point. But at low levels, it damages the credit transmission mechanism.” – bto: Und da darf nicht vergessen werden, dass die Banken noch faule Kredite bewältigen und das Eigenkapital stärken müssen. Beides nicht leicht, wenn man kein Geld verdient.

- “The Japanese experience proves that it is possible to keep monetary policy ultra-loose for decades and still fail to stimulate inflation while the health of the banking system deteriorates. The window to raise policy rates to address bank profitability is narrowing and the continent’s banks are at dire risk of being permanently weakened. The failure to achieve ‘escape velocity’ in Japan, and the staunch adherence to low rates, is a key reason why Japanese banks fail to cover their cost of equity.” – bto: Das System ist halt durchgehend faul.

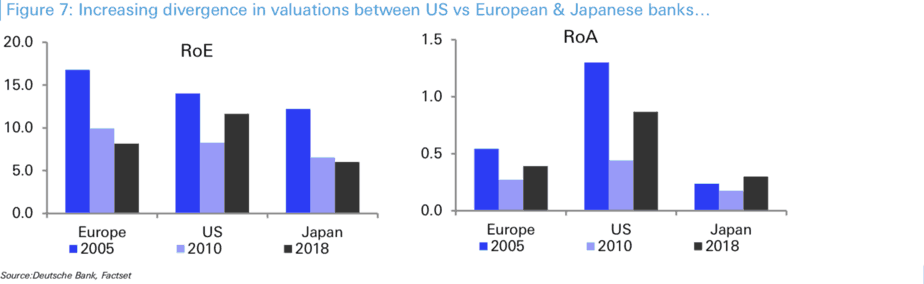

- “The negative deposit rate compounds the fundamental problem that European banking returns are not sustainable. Take return on assets. As a rule of thumb, a well-functioning banking system should allow banks to make one per cent on their assets. US banks are very close to this mark. In contrast, European and Japanese banks both return under half a per cent on their assets (…) If we narrow down returns to what investors recoup, return on equity, European and Japanese banks generate eight per cent and five per cent respectively, well behind their US peers at 12 per cent. It is also telling that returns on equity in Europe and Japan have fallen since the aftermath of the financial crisis while in the US they have risen.” – bto: In Europa haben wir also eine schlechte Situation verschlimmert, während in den USA die (erzwungene) Rekapitalisierung, aber vor allem die weitergehende Konzentration helfen. Damit will ich keineswegs sagen, dass das US-System über den Berg ist. Vermutlich braucht es nur eine weitere Krise, um auch dort das japanische Szenario einzuleiten.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

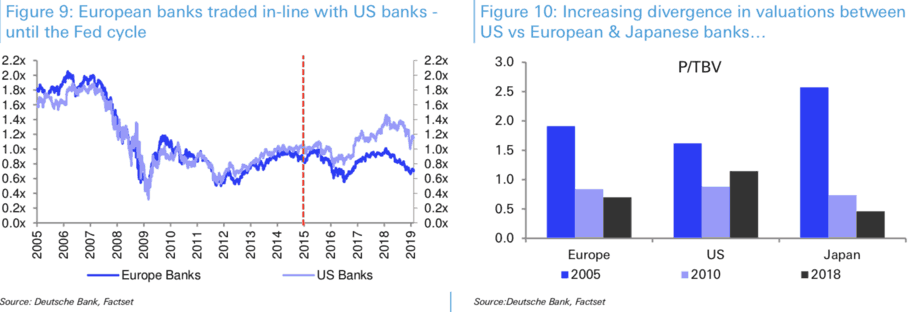

- “Given the situation in Europe increasingly mirrors that in Japan, it is no wonder that the share prices of European banks trade at just over half their book value, closer to Japanese valuations, while US banks trade over their book value. Of course, US banks have received a boost from nine interest rate hikes in the current cycle. In fact, since the cyclical low of three per cent in 2015, US bank net interest margins have improved to 3.5 per cent supported by the Fed rate cycle.” – bto: was nochmals zeigt, wie schlecht die Politik des billigen Geldes ist. Man verschleppt und verbreitert die Krankheit und macht das Problem damit größer, statt kleiner.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “It is a scary prospect that Europe may follow Japan. If the ECB can’t find ‘escape velocity’ on the path of rate normalisation, margin pressure could doublefrom five basis points last year to ten basis points. Over the next two to three years, that could drive down returns on equity from about nine per cent to seven per cent.” – bto: Man macht damit die Banken noch kränker. Kein Wunder, dass die Börsianer die Finger davon lassen.

Was tun? Die Analysten der Deutschen Bank zeigen die Hebel auf.

Der erste Hebel ist aus Sicht der Deutschen Bank eine Bereinigung des Marktes. Wie wir gleich sehen werden, gilt das besonders für Deutschland, wo nicht nur weniger Banken besser wären, sondern auch eine Reduktion des Staats- und Genossenschaftsanteils. Größere und mehr am Gewinn orientierte Einheiten wären nach dieser Logik zu bevorzugen.

Dass dies ökonomisch auch stimmt, zeigen ein paar Analysen:

- “If we look at the US, the five largest banks share between them half the assets of all US banks. In contrast, the five largest European banks share less than one-quarter of banking assets. In other words, the top end of the US banking market is more than twice as concentrated as the market in Europe. And this is before considering that the US is a single market whereas Europe does not have a full banking union and thus banks operate in an environment fragmented by 19 different markets, each with their own unique requirements. This fragmentation leads to structurally lower returns.” – bto: Und dies bedeutet nicht unbedingt bessere Konditionen für die Kunden. Richtig ist, dass die Banken höhere Preise schlechter durchsetzen können. Umgekehrt führen die ineffizienten Strukturen zur Notwendigkeit höherer Preise in der gesamten Branche. Mehr Effizienz (auch) durch größere Einheiten kann also durchaus beiden helfen: den Banken und den Kunden. Das gilt übrigens nicht für die Idee einer Fusion von Deutscher und Commerzbank. Das liegt daran, dass der Markt in Deutschland weiter fragmentiert bleibt und öffentliche und genossenschaftliche Anbieter dominieren.

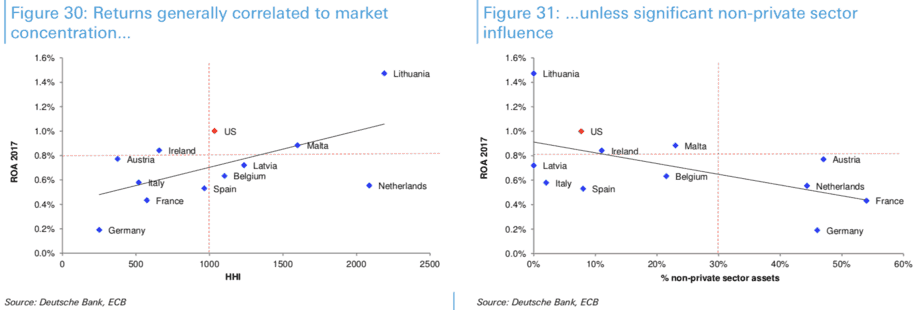

Das zeigt dann auch die Deutsche Bank. Links die Bedeutung der Konzentration und rechts die Folge eines hohen „nicht-privaten“ Anteils am Markt:

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

Deshalb lautet die zweite Forderung der Analysten, “(…) policymakers need to take steps to break down the barriers of non-private sector banks to encourage more consolidation both within the sector as well as with private-sector banks. Over time, the shift to greater market ownership of such assets is likely to benefit the banking system by raising market discipline, providing capital flexibility (…)” – bto: Das ist alles richtig. Es wäre – wie gesagt – auch im Interesse der Kunden. Weil heute nur Ineffizienz und Inkompetenz die Kosten treibt.

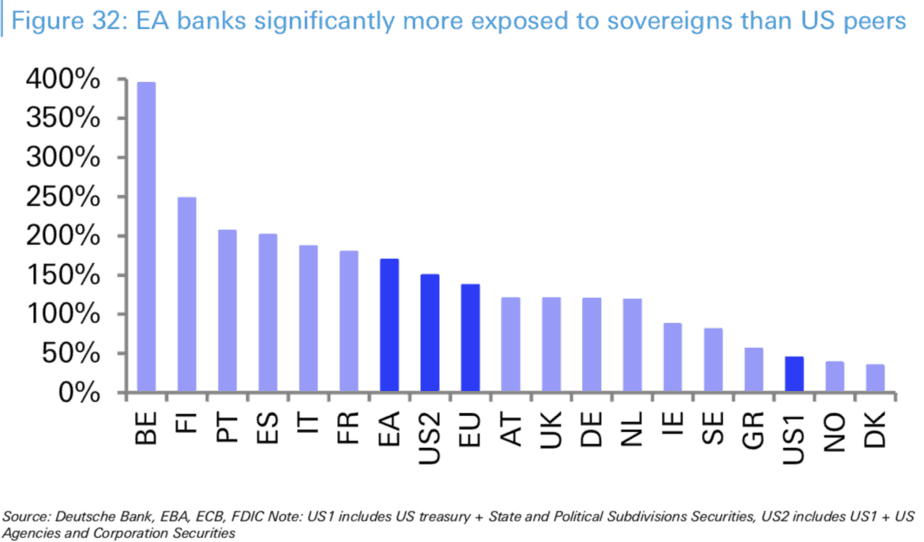

Danach geht es der Bank um die verhängnisvolle Verbindung zwischen Banken und Staaten. Wenn Staaten in Probleme kommen, verlieren die Anleihen des Staates in der Bankbilanz an Wert und bringen die Bank in Schwierigkeiten, was dann wiederum den Staat schwächt, soll dieser die Banken „retten“: “If Europe’s banks are to have a productive future, it is essential that any hidden surprises be brought out into the open. In this regard, regulators must reform the rules around sovereign debt, to which European banks are worryingly exposed and prevent the economy from falling into a doom loop. As the following chart shows, the average European bank has sovereign debt exposure equal to 170 per cent of its core tier one capital. That is more than triple the exposure of US banks.” – bto: Ich möchte anmerken, dass es noch weitere verdeckte Risiken gibt bei den Banken: die vielen faulen Kredite an den Privatsektor.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

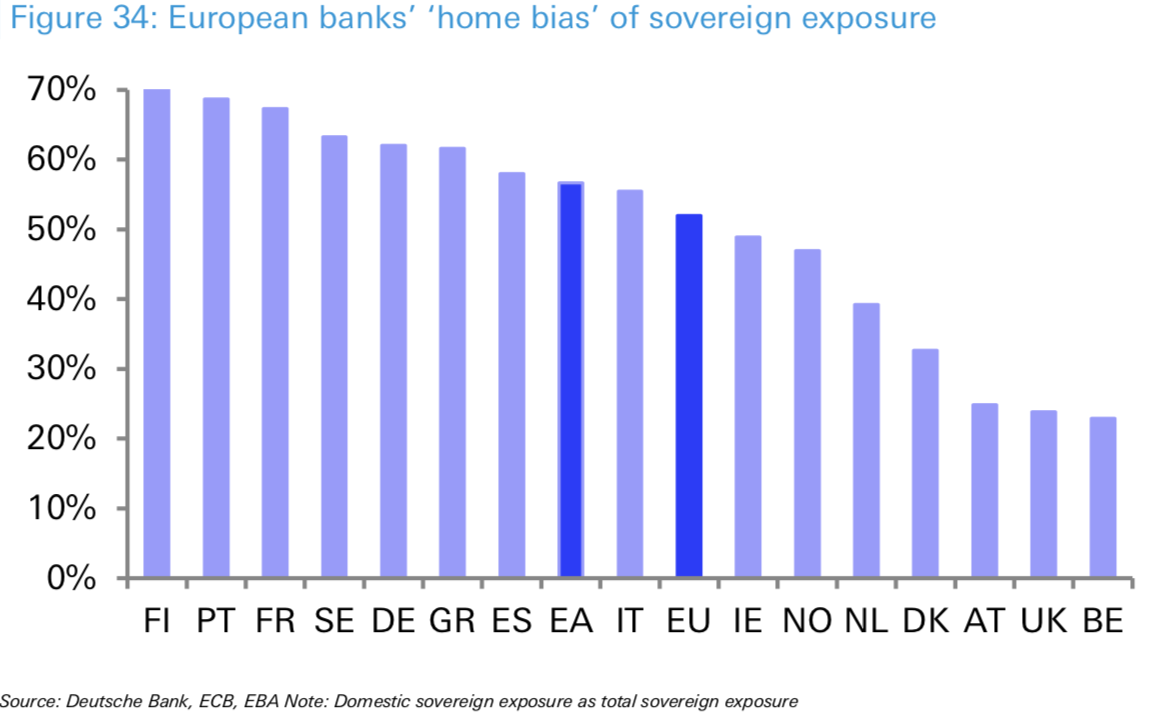

“Just as concerning as the overall scale of sovereign exposure is the significant ‘home bias’ of European banks. That is, about 60 per cent of an average European bank’s sovereign exposure is to their home government’s debt, as shown on the following chart.” – bto: Es gibt ja viele Ideen, wie man die Banken zu mehr regionaler Diversifizierung zwingen könnte. Dennoch muss man schon die grundsätzliche Frage stellen, ob wir nicht einfach eine falsche Geldpolitik und Geldschöpfungspolitik betreiben.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- Die Deutsche Bank sieht die Non-Performing-Loans nicht mehr als so ein großes Problem an: “(…) it is true that NPLs still comprise three per cent of European banks’ loans, triple the rate of US banks, and certain countries, including Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Ireland, still hold double-digit rates of NPLs. However, progress in Europe has been strong and the current three per cent rate is almost down two-thirds on the level six years ago. Furthermore, in recent years and quarters, NPL disposals have accelerated, notably in Italy, as bid-offer pricing ‘gaps’ have closed as a result of higher provisioning and an improvement in collateral values. Indeed, problem assets fell one-fifth between early 2017 and early 2018.” – bto: Das sind in der Tat gute Nachrichten, wenn man sie glauben kann.

- Was dann zu der – unweigerlichen – Empfehlung führt, die Bankenunion endlich zu vollenden: “A closer banking union will help break down some of the barriers that currently inhibit consolidation. For example, current European regulations mandate liquidity requirements be met at the subsidiary level in each country rather than at the parent domicile level. The common justification for this is the protection of national deposit insurance schemes. The downside is that banks are constrained in their ability to move funds across borders from one entity to another, while managing liquidity centrally. Thus, Europe needs to set effective cross-border capital and liquidity waivers to encourage cross-border consolidation. If Europe doesn’t trust itself, who will?” – bto: Ja, das klingt gut. Aber es gibt doch mehr als gute Gründe, sich nicht zu trauen. Deshalb haben wir ja auch die TARGET2-Salden.

- “The key stumbling block remains the creation of a fully-fledged European Deposit Insurance Scheme.” Und um das zu überwinden, schlagen die Analysten vor:

- “An ex-ante fund paid for by the banking industry, not unlike the FDIC in the US; (…)” – bto: unkritisch.

- “Ex-post ‘top up’ contributions should the fund be depleted (in an extreme scenario)” – bto: Das wirft die Frage auf, wer bezahlt. Hier geht es den anderen ja vor allem um das dumme deutsche Geld, weil wir doch denken, wir seien so reich.

- “Differentiated deposit insurance premium rates, unlike the US, to reflect differences in ‘riskiness’ not dissimilar to the risk-factor adjustment applied in calculating SRF risk-adjusted contributions but which also potentially reflect differences in insolvency and foreclosure frameworks; (…)” – bto: genau. Und morgen wirtschaften alle solide und ehrlich. Selten so gelacht. Haben wir nicht gerade in Europa genau diese Mechanismen alle ausgehebelt?

Sodann kommt eine weitere entscheidende Forderung der Analysten. Eine weitaus tiefergehende Kapitalmarktunion:

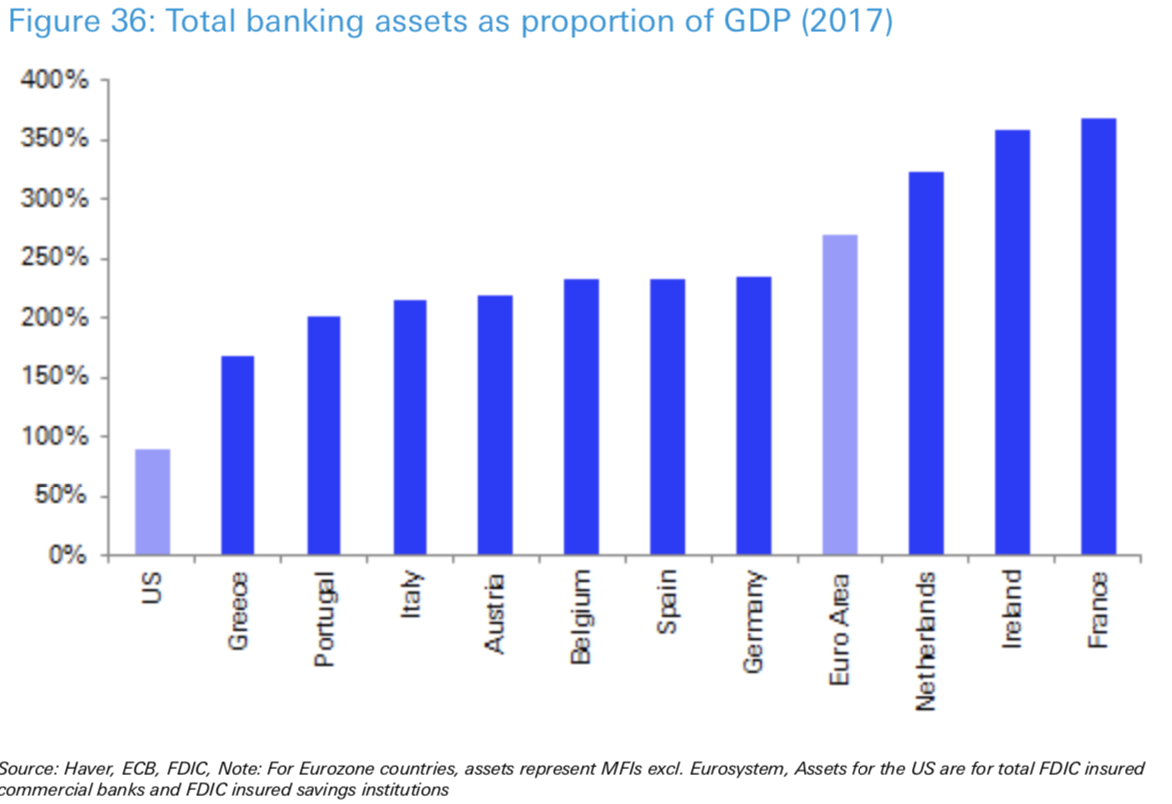

- “The size of Europe’s banking system introduces a frightening level of risk into the continent’s economy. Indeed, the banking market is 2.7 times larger than the entire eurozone economy, a vivid contrast with the US where the banking market is slightly smaller than the economy. In this regard, Europe’s overreliance on bank funding remains a key weakness of its financial system.” – bto: Man kann natürlich sagen, dass es nur daran liegt, dass wir keinen so ausgeprägten Markt für Verbriefungen haben wie die USA. Man könnte aber auch sagen, dass wir einfach mit zu vielen Schulden arbeiten. Ich denke, es ist beides, und nur der Weg der Verbriefung und der Erleichterung der Kreditschöpfung kann es nicht sein. Wir müssen die Schuldenlast verringern. Interessant ist, dass es vor allem ein Problem der Franzosen ist, deren Banken ein besonders großes Rad drehen und dann von deutschen Steuerzahlern – siehe Griechenland! – gerettet werden.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

- “The European securitisation market today stands at just €0.5trn, compared with $11.5trn in the US. Securitisation offers banks a diversified funding source and can facilitate the transfer of credit risk to others in the market, thereby providing capital relief that can be used to generate new lending to the real economy. In the process, it improves bank capital efficiency and profitability.” – bto: Da würde ich nicht widersprechen, erinnere aber daran, dass wir in der Finanzkrise gesehen haben, dass das mit der Risikoverteilung so eine Sache ist.

- “Experience in the US proves that the diversification of funding sources makes an economy more resilient throughout business cycles. During the financial crisis, the greater diversification of funding sources allowed the American economy to support the subsequent recovery. For example, the agency residential mortgage-backed securities market supported the ongoing financing of the housing market when private securitisation markets dried up.” – bto: Hm, das lag aber an der Staatsgarantie und nicht an der Verbriefung – oder?

- “In contrast, Europe’s recovery from the crisis was hampered by its dependency on bank lending. Right at the time when the economy was desperate for funding to provide growth, banks embarked on a deleveraging programme. A similar situation occurred during the subsequent sovereign debt crisis. (…) throughout both these crisis periods, a breakdown of monetary policy transmission due to bank stress hindered the allocation of capital in Europe.” – bto: wobei man klar sagen muss, dass dann die Verluste woanders anfallen. Anfallen tun sie aber so oder so. Richtig ist, dass die Banken lieber den Zombies Kredit geben, um Abschreibungen zu verhindern.

- “(…) given the tight relationship between economic and financial cycles, the stability and sustainability of Europe’s banking system should be one of the highest priorities for policymakers. The link between economic growth and bank credit means it is critical that the latter is stimulated by creating an environment that incentivises banks to lend rather than one that forces them to become increasingly risk-averse. The bifurcation of the US and Japanese experience over the last two decades has shown the policies that do and do not support a sustainable banking system, and thus, a growing economy. It is essential that Europe’s policymakers ensure that the continent takes a step down the same path trodden by the US and not that lumbered along by Japan.” – bto: Dazu gehört auch, anzuerkennen, dass ein guter Teil der Schulden eben nicht tragbar ist und in einem geordneten Prozess bereinigt gehört.

Es zeigt deutlich, wieso das europäische Bankensystem so krank ist und anfällig für die nächste Krise. Die vorgeschlagenen Instrumente wären sicherlich hilfreich – aber wären sie hinreichend? Da bin ich nicht so sicher …

Hier der Link zur DB-Studie: “How_to_fix_European_banking …_and_why_it_matters”

Der vielgeschmähte Dr Krall, der als einer der besten Bankenkenner gilt, hat in mehreren Vorträgen die sehr fragwürdige Rolle der EZB kommentiert, die, wie auch Dr.Stelter in seinem Blog bemerkt, falsche Aussagen macht.

So wurde das bekannt notleidende italienische Bankensystem als gesund dargestellt, weil die (laschen und getürkten) Prüfparameter der EZB dies aussagen würden.

Einer EZB, die solche irreführenden Bewertungen veröffentlicht, kann man genausowenig trauen, wie den teils kriminellen Rating-Agenturen.

Banken, wie auch die Deutsche Bank oder die Commerzbank, sind private Unternehmungen.

Die Führungen einiger dieser Unternehmen haben kläglich versagt.

Wenn in diesem Forum seit Jahren lamentiert wird, daß das Finanzsystem in Schieflage ist und die Rate der Insolvenzen ungesund niedrig ist („Zombies“), dann ist es notwendig, die Marktwirtschaft ihren Dienst tun zu lassen.

Die Allgemeinheit sollte die Versager nicht retten. Was getan werden sollte, ist folgendes:

1. Aufbau eines staatlich beaufsichtigten Systems von Einrichtungen, welche nur den Zahlungsverkehr abwickeln; keine Kredite, keine Spekulation, reine Dienstleistung etwa im Range der Versorgung der Bevölkerung und der hiesigen Industrie/Landwirtschaft etc. mit Infrastrukturleistungen wie Strassen, Schienen, Wasser, Strom (Kostendeckung aber keine Gewinnabsicht).

2. Zulassung von Banken, welche Kredit auf eigenes Risiko vergeben können, aber a) nie systemrelevant werden dürfen und b) nie gerettet werden.

D.h. strikte Trennung der Aufgaben. Das wäre ein wirklicher Neuanfang der Aussicht auf stabile Verhältnisse hätte. Das herumdoktern an Symptomen wird keine stabile Lösungen der Probleme bringen.

Nicht alle werden dieser Sichtweise zustimmen, bevor jetzt der eine od. andere zu Beschimpfungen oder Totschlagargumenten Anlauf nimmt, ist jeder aufgefordert eigene konstruktive Vorschläge zu unterbreiten, wie es in Zukunft besser funktionieren kann.

Interessante Analyse, für mich zeigt sie im Kern zwei substantielle Unterschiede zwischen den USA und EWU/Japan: die Demographie und die Größe des Verbriefungsmarkts (u.a. des Schattenbanksystems).

Diese werden besonders deutlich, wenn wir uns anschauen, wie Banken Geld verdienen:

1.) durch durch Fristentransformation. Vereinfacht kontrolliert eine Zentralbank immer nur das kurze Ende der Zinsstrukturkurve, das lange Ende wird am Markt gebildet und spiegelt die Erwartungen der Teilnehmer an die Wirtschaftsentwicklung wider.

Auch in den USA hat sich die Strukturkurve in Teilen invertiert, hier also aktuell kein großer Unterschied erkennbar. In Europa und Japan ist der demographische Faktor jedoch stark negativ, deswegen würde ich darauf tippen, dass die Kurve dort noch länger flach bleibt. Weiterhin ist die Fiskalpolitik im Euroraum eher restriktiv.

2.) durch Aufnahme von Bonitätsrisiko. Hier kommt auch die Marktmacht einzelner Banken ins Spiel, da Unternehmen aufgrund des kleinen Verbriefungsmarkts wenige Alternativen haben und Zinsnehmer sind. Eine Konsolidierung des Bankensektors könnte somit tatsächlich gegen das geringe Zinsniveau helfen, dagegen spricht jedoch eine sinkende NPL-Quote (weniger Ausfälle = geringerer Zins). Eine stärkere Investitionsaktivität der starkten Unternehmen würde außerdem zu einer geringeren Unternehmens-EK-Quote führen, wodurch Banken auch von guten (profitablen) Schuldnern mehr Zins verlangen könnten.

3.) durch Dienstleistungen. Aktuell greifen sich auf beiden Seiten des Atlantiks dynamische Fintechs und Tech-Unternehmen die profitablen Häppchen des Privatkundengeschäfts, es bleibt somit das Firmenkundengeschäft, insbesondere der Verbriefungsmarkt (Debt/Equity Capital Markets).

Hier wird in den USA viel Geld verdient, denn die weltweiten Dollarreserven (Leitwährung) suchen nach Anlageformen und amerikanische Unternehmen suchen günstige Refinanzierung. Auch der EWR könnte davon profitieren, wir generieren nämlich durch unseren Exportüberschuss ebenfalls EUR-Geldmarktreserven im globalen Ausland, welches zinstragend angelegt werden will. Dadurch könnten viele Assets die Bankenbilanzen verlassen, nur die Regulierung sollte schleunigst nachziehen, um flexibel auf Entwicklungen reagieren zu können und die tatsächliche Haftung der Akteure sicherzustellen.

Auch steigt der Bedarf an Staatsanleihen beim Anwachsen des Schattenbanksystems, da dieses System ein besichertes System ist – das verschafft Regierungen weiteren Spielraum in der Fiskalpolitik und kann auch ganz ohne EZB-Intervention zu geringen Refinanzierungskosten führen. Einlagen würden etwas weniger bei Banken gehalten (was diese von der Bürde der Wiederanlage befreit) und tendenziell mehr in produktiven Investments, für welche spezielle Vehikel gegründet werden können.

Leider sind die europäischen Institute nicht mehr stark im Investmentbanking (die Franzosen) oder durch und durch korrupt (die Deutsche Bank). An den Sparkassen als finanzielle Grundversorgung für die Bevölkerung würde ich nicht rütteln, die konsolidieren sich aktuell ja auch selbst sehr stark.

Steuernachlese: https://think-beyondtheobvious.com/stelters-lektuere/zur-besteuerung/#comment-65019

LG Michael Stöcker

Genau Herr Stöcker, das System ist völlig entartet. Leider hilft da kein “An-die-Kette-legen”. Jedes FIAT-Money-System ist irgendwann am Ende, da es nichts mehr umzuverteilen gibt. Deutschland wird genauso heruntergewirtschaftet wie die DDR und die weiteren Ostblockländer mit Planwirtschaft und Fehlinvestitionen.

Die Lösung ist eine übersichtliche Gesetzgebung, niedrige Steuern, solide Eigentumsrechte, eine stabile Geldpolitik und vor allem Investitionen in die Bildung.

@Kassandra: Ich würde nur zwei Sachen anders formulieren: “faire” Steuern statt “niedrige”. Die dürfen für wirklich große Vermögen (nicht für große Einkommen) aus meiner Sicht gerne höher sein.

Und einen solide Migrationspolitik. Sonst nützen Ihnen all die anderen Dinge nichts, denn dann blähen Sie den Sozialstaat massiv auf und landen auch im Sozialismus.

@ Susanne Finke-Röpke

” Die dürfen für wirklich große Vermögen (nicht für große Einkommen) aus meiner Sicht gerne höher sein.”

Bei > 1 Mio darf für mich auch der Spitzensteuersatz deutlich höher sein. Der war auch unter Kohl zeitweise noch bei 56%.

„Jedes FIAT-Money-System ist irgendwann am Ende, da es nichts mehr umzuverteilen gibt.“

Wann ist denn bei Ihnen „irgendwann“? Die Briten sind seit rund 325 Jahren mit ihrem Fiatgeldsystem sehr erfolgreich am Markt der Währungen.

Richtig ist allerdings, dass bislang noch jede Zivilisation früher oder später untergegangen ist. Ob es IMMER am Geldsystem gelegen haben mag, das darf wohl bezweifelt werden.

Wie immer kommt es auch hier auf das richtige Verständnis an und sodann auf die richtige Dosis von Fiatgeld und Kreditgeld. Haben Sie bereits das korrekte Verständnis und können den Unterschied zwischen Fiatgeld und Kreditgeld benennen? Das Stichwort hierzu lautet: Monetärer Dualismus.

Man kann aber nicht nur an zu viel Umverteilung zugrunde gehen (DDR & Co.) sondern auch an zu wenig (USA & Co.). Von daher gab es ja schon immer die biblischen Erlassjahre. Wer diese zukünftig nicht mehr als disruptives Ereignis möchte, der sollte einen stabilisierenden Dauerentschuldungsmechanismus etablieren. Mein Vorschlag hierzu sollte ausreichend bekannt sein:

Die Schulden werden via zentralbankfinanziertem Bürgergeld an das Bilanzkreuz der Zentralbank genagelt und ex post via Erbschaftssteuer wieder vom Bilanzkreuz genommen (Yin und Yang). Damit können wir zugleich den Finanzkapitalismus angelsächsischer Prägung zu Grabe tragen und als Rheinischen Kapitalismus wieder auferstehen lassen. Vielleicht klappt’s dann ja auch irgendwann mal mit der Demokratie.

„Die Lösung ist eine übersichtliche Gesetzgebung, niedrige Steuern, solide Eigentumsrechte, eine stabile Geldpolitik und vor allem Investitionen in die Bildung.“

Jetzt müssen Sie uns „nur“ noch erklären, wie wir rechtzeitig von A nach B kommen, damit Sie Ihrem Namen nicht alle Ehre erweisen. Ich unterstütze alle Ihre Punkte; aber ohne ein korrektes Verständnis unseres Geldsystems werden wir B niemals erreichen: https://zinsfehler.com/2019/01/23/warum-konnen-wir-unser-geldsystem-nicht-richtig-verstehen/

LG Michael Stöcker

@Herr Stöcker

“Die Briten sind seit rund 325 Jahren mit ihrem Fiatgeldsystem sehr erfolgreich am Markt der Währungen.”

Nein. Bis 1931 war das GBP konvertibel zu Gold, für je 1 GBP konnten Sie bei der britischen Zentralbank eine “Sovereign”-Goldmünze eintauschen.

Bis heute steht auf den Pfund-Banknoten “I PROMISE TO PAY THE BEARER ON DEMAND THE SUM OF [Nennwert der Banknote]”, aber seit der Aufhebung der Gold-Konvertibilität ist das eine sinnlose Phrase. Vor 1931 war das noch ganz anders.

„Vor 1931 war das noch ganz anders.“

Ihr Glaube in Ehren, Herr Ott, die Fakten sprechen mal wieder eine andere Sprache. Der Goldstandard war schon IMMER eine Schönwetterveranstaltung und wurde schon IMMER einkassiert, wenn es ernst wurde. Alle Herrscher, die halbwegs bei Verstand waren, haben sich noch NIE Goldene Fesseln angelegt oder aber wurden bitter abgestraft, wenn sie das Realignment falsch eingeschätzt hatten: https://www.gold.org/sites/default/files/documents/1925jul.pdf

LG Michael Stöcker

Sicher, Herr Stöcker, wenn es ernst wird, dann brechen Regierungen ihre Versprechen. Heutzutage sogar ganz ohne Goldstandard.

Wer damals sein britisches Papiergeld in Sovereigns eingetauscht hat, freut sich übrigens über 23400% Gewinn. Die Sovereigns haben immer noch einen Nennwert von jeweils 1 GBP, aber alleine der Materialwert des ein einer solchen Münze enthaltenen Goldes (7,3 Gramm Feingewicht Gold pro Münze) ist fast aktuell rund 235 GBP. Das zeigt, wie “sehr erfolgreich” das britische Fiatgeldsystem in den letzten knapp 100 Jahren bei der Gewährleistung der Geldwertstabilität war, oder? ;)

Ein wichtiger Punkt fehlt mir bei der heutigen Analyse. Es ist dieser Satz im Vorwort von Folkerts-Landau, der es in sich hat:

„At the same time, US banks receive about $40bn (2.4% on $1.65 trn) on their excess reserves.”

Hier ist einer der ganz wesentlichen Punkte für die höhere „Profitabilität“ des amerikanischen Bankensektors. Ein echter parasitärer Free Lunch vom amerikanischen Steuerzahler für die ausgecashten Bilanzen der unterbezahlten Hungerleider der Wallstreet.

Dass sich hierüber keiner aufregt ist wohl der Tatsache geschuldet, dass kein Außenstehender die Funktionsweise des Geldsystems versteht, geschweige denn die Funktionsweise der IOER (interest on excess reserves).

Es sind in der Tat 40 Mrd. USD, die hier direkt von der Fed an die Banken verteilt werden (letztlich also an die Eigentümer der Fed; ein klassisches Insichgeschäft)) und somit den Gewinn der Fed mindern und somit auch nicht als Ausschüttung an den Haushalt zur Verfügung stehen.

Ich frage mich seit den mehrfachen Erhöhungen seit Ende 2015, warum hier keiner aufbegehrt. Hier greift letztlich eine demokratisch nicht legitimierte halbprivate Institution in das Königsrecht des Parlaments ein: Das Budgetrecht. Ach ja, ich vergaß: GS steht natürlich über dem König und erfüllt lediglich Gottes Werk auf Erden.

Was muss noch alles geschehen, damit dieses entartete System endlich wieder an die Kette gelegt wird? Schirrmachers Anklage wird durch die Wirklichkeit leider immer wieder getoppt: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/buergerliche-werte-ich-beginne-zu-glauben-dass-die-linke-recht-hat-11106162.html

LG Michael Stöcker

@ Michael Stöcker

Wieder einmal das Thema Verteilung.

Gut, man kann sich darüber aufregen.

Was aber machen die Banken mit den $ 40 Mrd?

Ich kann nicht erkennen, warum sie den Investitionen zugutekommen sollten.

Die Banken dürften im Wesentlichen die Assetpreise nach oben treiben.

Damit wird das System anfälliger.

Vor allem darüber sollte man sich Gedanken machen.

@ Dietmar Tischer

„Was aber machen die Banken mit den $ 40 Mrd?

Ich kann nicht erkennen, warum sie den Investitionen zugutekommen sollten.

Die Banken dürften im Wesentlichen die Assetpreise nach oben treiben.“

Was meinen Sie mit „den Investitionen zugutekommen“? Denn für Investitionen der Industrie via Kreditvergabe werden diese 40 Mrd. nicht benötigt. Und zum Hochtreiben der Assetpreise benötigen sie diese Mittel ebenfalls nicht. Das geht ganz einfach über ein Eigengeschäft.

Die Assetpreise könnten allerdings mit den 40 Mrd. indirekt auf diesem Weg hochgetrieben werden:

Bonuszahlungen an die „Leistungsträger“, die anschließend damit Assets erwerben, weil kein weiterer Ferrari mehr in die Garage passt.

„Damit wird das System anfälliger.

Vor allem darüber sollte man sich Gedanken machen.“

Da bin ich ganz Ihrer Meinung. Aber Sie wehren sich ja gegen das Thema Verteilung; sogar dann, wenn WEGEN unterlassener Verteilung der Kuchen schrumpft.

LG Michael Stöcker

@ Michael Stöcker

>Was meinen Sie mit „den Investitionen zugutekommen“? Denn für Investitionen der Industrie via Kreditvergabe werden diese 40 Mrd. nicht benötigt.>

Habe nicht behauptet, dass sie dafür benötigt werden.

Sie könnten aber dafür eingesetzt werden z. B. von den hochbezahlten Leuten, an die das Geld verteilt wird.

Werden Sie doch nicht gleich nervös, bei mir müssen Sie nicht die loanable funds theory wittern.

>Aber Sie wehren sich ja gegen das Thema Verteilung; sogar dann, wenn WEGEN unterlassener Verteilung der Kuchen schrumpft.>

Sie stellen meine Position falsch dar.

Ich bin weder gegen Verteilung (in Maßen), noch bin ich für einen Schrumpfung des Kuchens.

Ich bin gegen Ihre „99% zu 1%-Umverteilungslösung“, weil ich diese für Illusion halte und zudem der Meinung bin, dass der Kuchen damit nicht wächst oder nicht so, wie er wachsen könnte.

Meine Vorstellung ist Anreize fürs Investieren von den 1% abwärts, weil das den Kuchen wachsen lassen würde, was die Umverteilung – nach (politischer) Lage der Ding für den Konsum bestimmt – nicht leisten kann.

Habe ich hier schon x-mal dargelegt.

@ M.S.

“warum hier keiner aufbegehrt.”

“Keiner” ist natürlich nicht richtig, wolfstreet hat das immer mal wieder als Thema. Aber natürlich kein Thema in der breiten Masse.

https://wolfstreet.com/2019/01/10/fed-paid-banks-38-5-billion-in-interest-on-reserves-in-2018-slickest-annual-wealth-transfer-from-taxpayers-to-banks/

bto: “…sondern auch eine Reduktion des Staats- und Genossenschaftsanteils.”

Hier möchte ich energisch gegen Ihre Verquickung des genossenschaftlichen Systems mit dem Staatssystem protestieren.

Der Genossenschaftsanteil ist gesund, mit den wenigsten Ausnahmen nicht systemrelevant, profitiert nicht von Staatsgarantien, befindet sich zum Großteil im Eigentum seiner Kunden und ist rein privat organisiert. Es besteht kein Grund, hier staatlicherseits die marktwirtschaftlichen Ergebnisse zu beeinflussen. Genauso gut könnten Sie alle kleinen Mitglieder des Bundesverbands Deutscher Banken zum Anschluss an die Großen auffordern, was den Wettbewerb ja auch reduzieren würde; seltsamerweise tun Sie das nicht.

Etwas anderes ist es beim Staatsanteil, sprich Sparkassen und vor allem Landesbanken. Hier gebe ich Ihnen recht, denn die Finanzdienstleistungen sind (abgesehen von staatlichen Förderbanken wie der KfW) keine öffentliche Aufgabe, solange der Markt auch für Randgruppen (z.B. die mit P-Konto) ausreichend funktioniert.

Sie gehen mit Ihrer Argumentation den Vertretern des systemrelevanten Großkapitals auf den Leim, die im Wettbewerb gegen die kleine, aber flexiblere Konkurrenz nicht so punkten konnte, wie sie es gerne getan hätten und tun würden. Es ist aber nicht Aufgabe des Staates, die Kundenentscheidungen am Markt zu korrigieren, was er mit unsinnigen Regularien, die aufgrund der Fehler von Großbanken entstanden sind, jetzt wegen schlechterer Fixkostendegression der kleinen Banken sowieso schon tut.

Bitte fallen Sie auf solche Dinge nicht herein, dafür sind Sie doch eigentlich zu liberal. Deutschland lebt von der Industrie UND vom Mittelstand und letzterer braucht auch mittelständische Banken. Wenn Sie nur einen Funken Interesse am Erhalt der Marktwirtschaft haben, helfen Sie die Genossenschaftsbanken schützen und nicht plündern. Schützen heißt aber einfach nur gleiche Rahmenbedingungen und keine Subventionen.

Zur Erläuterung in eigener Sache: Nein, ich arbeite nicht für eine Genossenschaftsbank, aber ich freue mich, dass große Teile meiner Familie dort Kunden sind.

@Fr. Finke-Röpke: Ich bin mir nicht sicher, ob Herr Dr. Stelter wirklich den genossenschaftlichen Sektor schrumpfen lassen will. Er analysiert ja die Meinung der Deutschen Bank:

bto: “Der erste Hebel ist aus Sicht der Deutschen Bank eine Bereinigung des Marktes.”

Aus Sicht der Dt. Bank ist es klar: Weniger Wettbewerber, höhere Margen, bessere Gewinne. Nach der Methode kann ich aber in jeder Branche jedes Unternehmen fragen, ob es nicht die Beseitung von ein paar Wettbewerbern befürworten würde. Viel Gegenwind ist bei so etwas nicht zu erwarten. Das ist m.E. nicht bankspezifisch.

@Herr Selig

Ja, es ist wirklich keine Überraschung, dass die Banken gerne weniger Wettbewerb hätten, um höhere Gewinne erzielen zu können. Das steigert die Ertragskraft und hilft den Bankern, aber niemandem sonst.

Ähnlich hilfreich: Cum-Ex-Betrug nicht zur Anklage bringen, sondern verjähren lassen. Läuft gerade vor unseren Augen ab. Damit sind immerhin 30 Milliarden Euro zu “verdienen”: https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/steuern-cumex-ermittlungen-101.html

Off the Topic:

Der “Abgang” von Holger Steltzner bei der FAZ wurde soweit ich sehe hier noch nicht thematisiert. Wäre vielleicht auch ein interessantes Thema, da man kaum etwas über die Hintergründe in Erfahrung bringen kann. Sollte hier eventuell ein weiterer kritischer Kommentator im Sinne der Ansichten dieses Blogs geräuschlos aus der Medienlandschaft aussortiert werden?

@Herrn Hans-Peter Stumpf:

Ein guter Hinweis.

Ich vermute mal, zwei mögliche Gründe kommen dafür in Frage:

1. Wer wie Herr Steltzner im Jahr 2016 einen Preis von Roland Tichy entgegennimmt, ist nicht mehr gerade systemkonform im nach links gewanderten Kollegenkreis. Vielleicht will er aber mit 56 Jahren noch rechtzeitig gehen, bevor die Auflage des Blatts noch weiter sinkt und Sparmaßnahmen ergriffen werden müssen.

2. Möglich wäre auch, dass er seinen Gesellschafteranteil (lt. Wikipedia sind die 4 Herausgeber neben der FAZIT-Stiftung alle auch Miteigentümer) rechtzeitig verkauft hat, solange er noch richtig Geld dafür bekommt. Denn ein Rückgang der Auflage von 41 % in den letzten 20 Jahren laut Wikipedia) hat den Anteilswert wohl nicht gesteigert. Und als Wirtschafts- und Finanzjournalist kann er rechnen. Die Alteigentümer der Süddeutschen Zeitung haben vor über 10 Jahren auch noch rechtzeitig den Absprung geschafft.

3. Möglichkeit: Er hat ein wirklich attraktives Jobangebot oder kann aufgrund persönlichen Wohlstands frühzeitig privatisieren und kümmert sich intensiv um seine Freizeit…^^

@ Hans-Peter Stumpf

Ich stimme den Überlegungen von @ Susanne Finke-Röper zu.

Die FAZ ist nicht so „kritisch“ wie dieser Blog, muss es auch nicht sein im Sinne einer breiteren Meinungsvielfalt. Sie ist aber keine Zeitung, die ihre Redakteure ersichtlich nach Meinung aussortiert.

Wenn doch, dann gäbe es bei der FAZ längst keinen Rainer Hank mehr.

Die FAZ degeneriert mittlerweile leider mehr und mehr zu einer taz mit interessanteren Stellen- und Todesanzeigen.

Ich glaube, das Endziel der Printmedien ist, sich mit ihrer Berichterstattung so nahe an die Regierung heranzukuscheln, dass diese wiederum eine Haushaltsabgabe für Printmedien einführt. Quasi ein Rundfunkbeitrag für Zeitungen. Wenn alles zwangsfinanziert wird, spielen sinkende Auflagen keine Rolle mehr. Widerständler wie Stelzner stören dabei natürlich, die müssen nach und nach entsorgt werden oder von selbst gehen, bis irgendwann Regierung und Medien komplett auf einer Linie sind.

Zwischen Steltzner und Hank gibt es 10 Jahre Altersunterschied. Hank (und mit ihm wohl so einige Kommentatoren hier vor Ort) erfüllt somit die Kriterien von Max Planck viel besser als Steltzner:

„Eine neue wissenschaftliche Wahrheit pflegt sich nicht in der Weise durchzusetzen, daß ihre Gegner überzeugt werden und sich als belehrt erklären, sondern vielmehr dadurch, daß ihre Gegner allmählich aussterben und daß die heranwachsende Generation von vornherein mit der Wahrheit vertraut gemacht ist.“

Steltzner hätte noch weitere 10 Jahre veraltete Lehrbuchweisheiten/Ideologie zum Besten geben können. Insofern war dieser Schritt durchaus richtig, sofern es bei der FAZ tatsächlich einen Erkenntnisfortschritt gegeben haben sollte. Sein Kollege Zschäpitz tastet sich immerhin vorsichtig heran: https://www.welt.de/finanzen/plus190610081/Modern-Monetary-Theory-Wenn-Schulden-nicht-Gefahr-sondern-Verheissung-sind.html .

Mal schauen, wann Zschäpitz das Ganze auch wirklich verstanden hat. Hier kann er sich kundig machen: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-03-21/modern-monetary-theory-beginner-s-guide

LG Michael Stöcker

Ah, Herr Stöcker, Sie sind heute ja ganz besonders charmant und bringen tatsächlich das “Meine-Gegner-sind-schon-alt-und-sowieso-bald-tot”-Argument.

Darf ich fragen: Wie alt sind Sie eigentlich?

Sie dürfen, Herr Ott: Gleicher Jahrgang wie Dr. Stelter (1964).

LG Michael Stöcker