Wie bekäme man die Staatsschulden in den Griff?

JP Morgan beschäftigt sich mit der Entwicklung der Staatsschulden in der Welt und wirft die Frage auf, ob man diese unter Kontrolle bringen könnte. Interessante Diskussion:

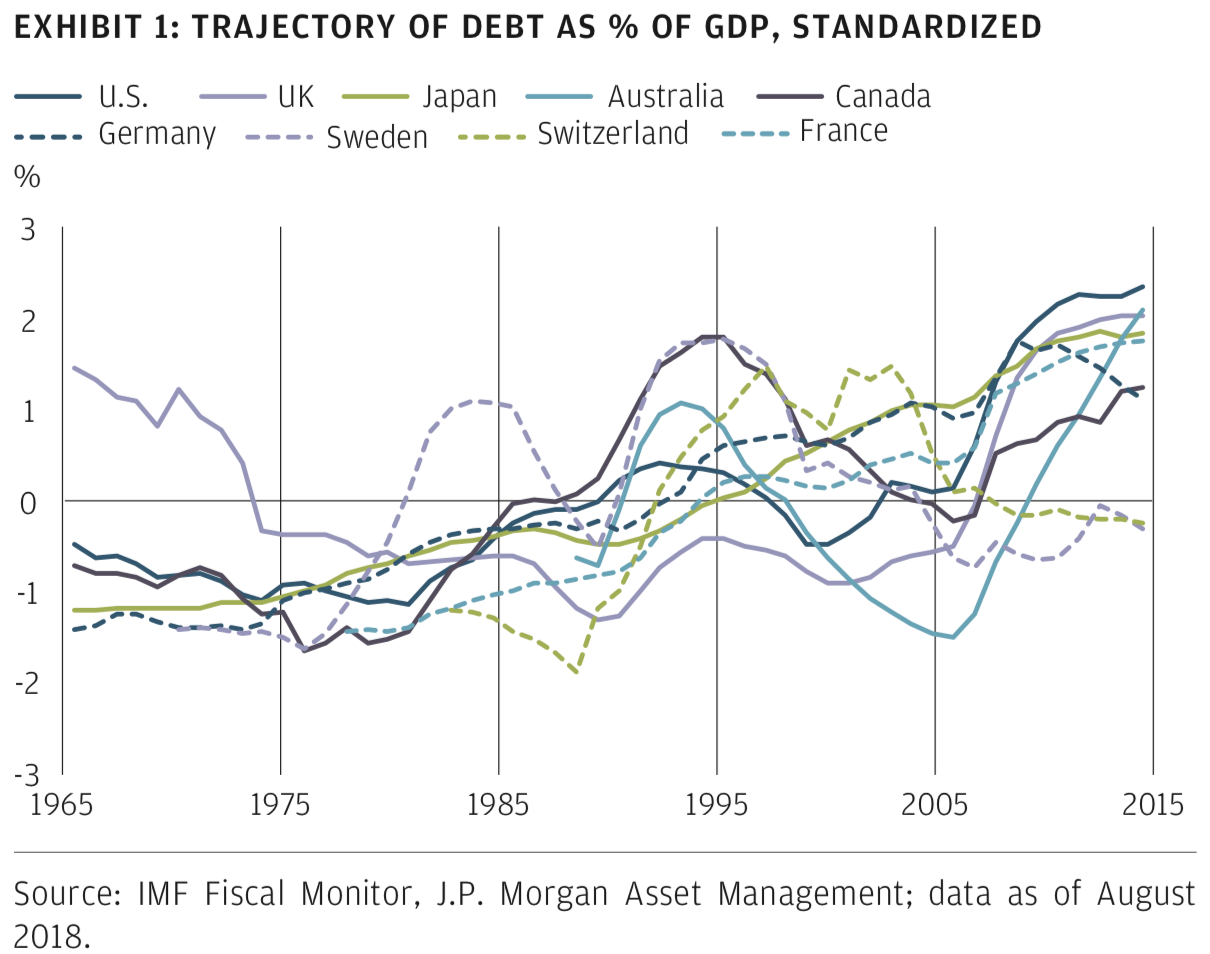

Zunächst die einfache Feststellung, dass es in den meisten Staaten mit den Schulden bergauf geht, egal, was die Politiker erzählen. Deutschland natürlich die positive Ausnahme, allerdings nur dann, wenn man kameralistisch rechnet und das tun wir ja leider alle bei dem Thema:

Quelle: JP Morgan

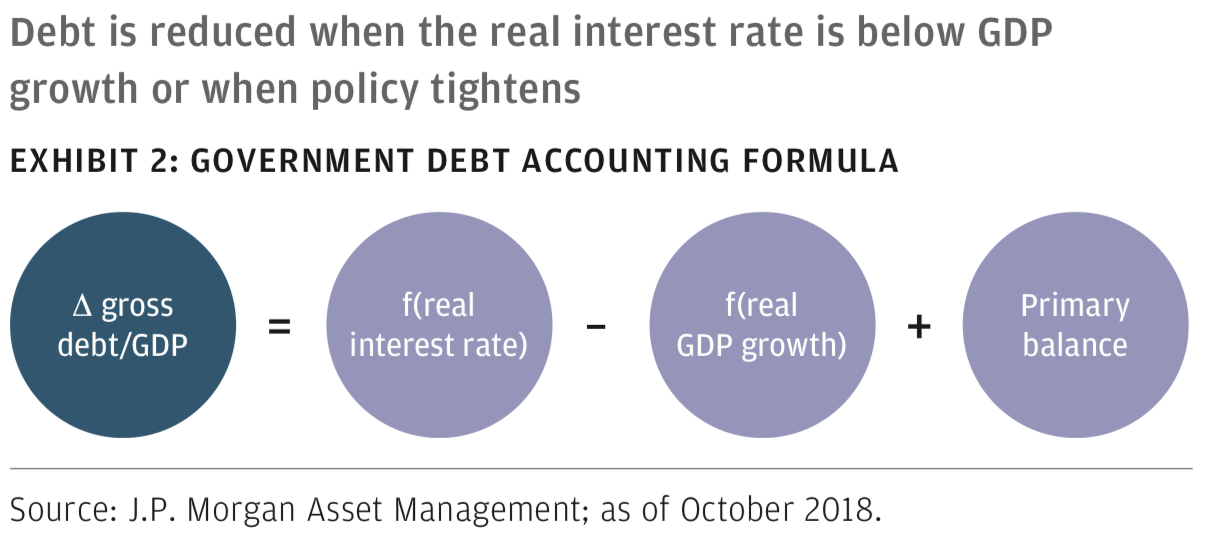

- “(…) it is helpful to disentangle its underlying drivers. To do so, we follow an accounting framework that parses changes in the debt-to-GDP ratio, separating out contributions from the real interest rate, real GDP growth and the government’s primary balance (the fiscal balance excluding interest payments) (Exhibit 2). The primary balance contains a cyclical component, reflecting how government finances deteriorate during periods of economic contraction and improve during expansions, and a structural component that more reflects the role of policy.” – bto: Das ist weder neu noch revolutionär, man muss es halt nur machen. Und gilt auch in Zukunft, weshalb der Hinweis, dass dieses Bild im Oktober 2018 gemacht wurde, mehr als überflüssig ist.

Quelle: JP Morgan

- “During the recent years of debt drift, looser fiscal policy played an overwhelming role. We know this because other factors leaned against it. For one, the balance of real interest rates and growth has generally been exerting downward pressure on debt levels. We estimate that from 2010–17 the fact that growth rates were higher than prevailing interest rates subtracted an average of 1.2 percentage points (ppt) annually from debt-to-GDP levels in each country (Exhibit 3). (…) In stark contrast, since 2010 the policy component of the primary balance has added 1.3ppt to debt levels annually, on average, for each country. All in all, monetary, growth and cyclical conditions have been generally favorable for debt consolidation, but both have been overwhelmed by sustained shifts in fiscal policy.” – bto: Wir haben also in der guten Zeit nicht konsolidiert. Wir Deutsche ja auch nicht, wie Leser von bto wissen.

- “It seems natural to conclude that government debt will necessarily restrain future growth — that lower taxes today will mean higher taxes in the future to ensure that debt is repaid — so that growth today comes at the expense of growth tomorrow. But history tells us this is not necessarily the case. In a number of instances in the past, high debt levels were tackled without significantly impeding growth.” – bto: so zum Beispiel nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg durch hohes nominales Wachstum bei gleichzeitig deutlich zu geringen Zinsen.

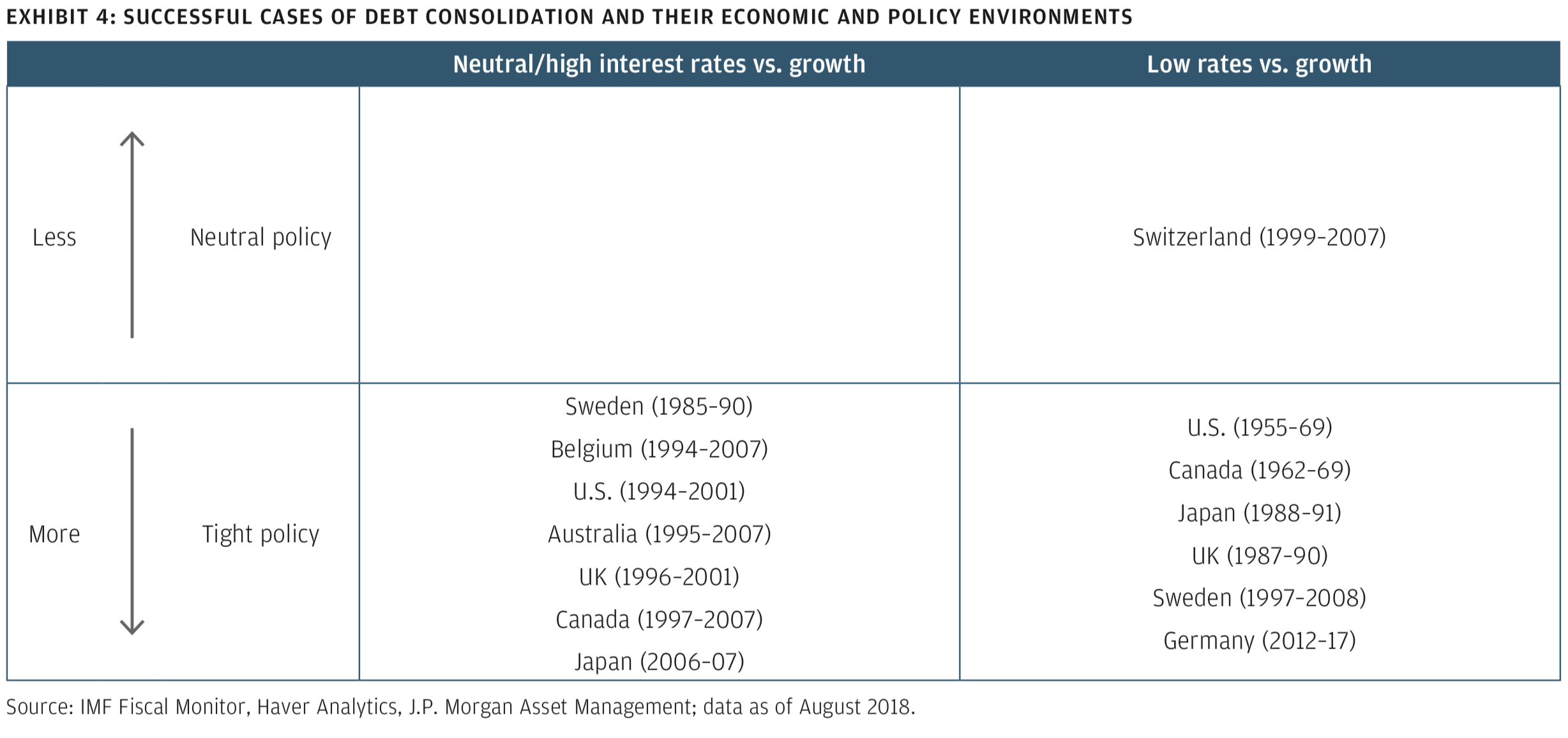

- “(…) of the 14 successful debt consolidations that we identify, 13 occurred during periods of relatively tight fiscal policy (high primary surpluses), suggesting that at least some belt-tightening is necessary. The number of consolidation experiences that took place amid relatively low vs. relatively high rates is evenly split, implying a significant — but not necessary — role for low rates relative to growth.” – bto: Also sagt JP Morgan, man kann doch sparen, um die Schulden in den Griff zu bekommen, ohne die Wirtschaft abzuwürgen. Italien ist nun sicherlich ein Beispiel, wie es nicht funktioniert. Klar dürfte sein, dass es ohne Wachstum nicht geht.

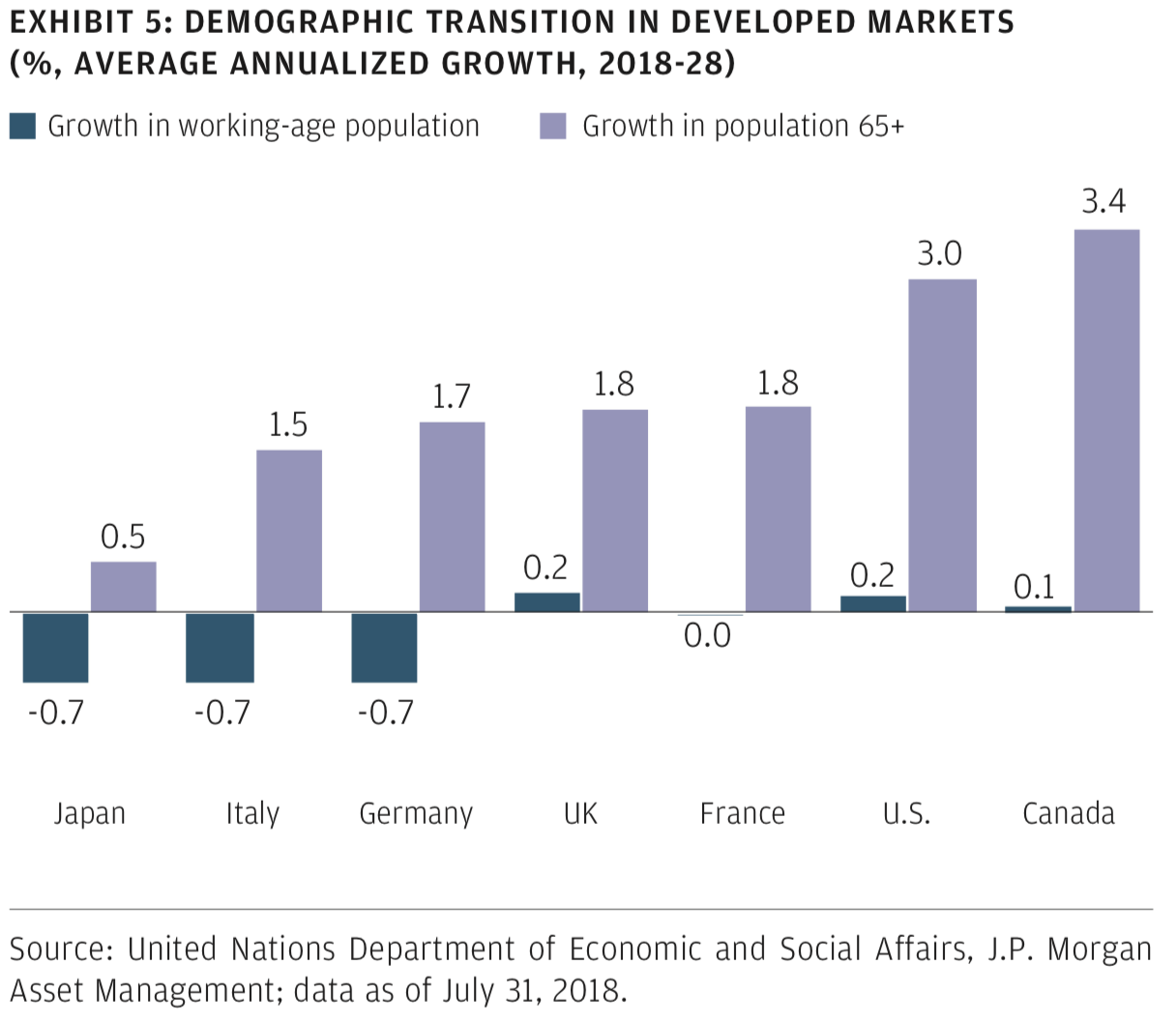

- “We conclude with a rough assessment of DM economies’ ability to replicate the successful consolidation experiences of the past and, where it is likely that they can, what conditions would be necessary. To begin, the ability of the governments in the developed world to improve their primary balance position looks challenging on a number of fronts. The most acute challenge is the demographic shift set to take place in the coming decades. While the severity of the problem differs by country, all countries in the developed world are seeing a slowing rate of growth of their working-age populations and a rapid expansion of those of pensionable age.” – bto: Und wie ich immer wieder erkläre, führt das zu weniger Wachstum und höheren Kosten. Dann explodieren die Sozialausgaben und weil man nicht vorgesorgt hat – bzw. es bei uns verschlimmert hat – bleiben dann nur Schulden, will man die Leistungsträger nicht aus dem Land vergraulen. Aber das scheinen unsere Politiker einfach nicht verstehen zu wollen. Dabei ist es ein so einfaches Bild:

- “Tax contributions peak at around 50 years of age and then slow dramatically from the mid 60s, at which point many people no longer pay income tax (…) government spending per person increases substantially from age 70 as the provision of health and social care ramps up. Given that around half of those eligible to vote in the developed world are older than 50, governments are likely to find reducing pension and health care benefits politically challenging.” – bto: Umso dümmer ist es, vor dem Renteneintritt unrealistische Erwartungen zu wecken, in dem man riesige Versprechen macht.

- “(…) we do not anticipate a significant tailwind from financial conditions. In other words, we do not pencil in large imbalances between growth and interest rates. Should the next recession cause liquidity-trap dynamics like the post-GFC period’s, leading to a sustained period when rates are lower than growth, we see little potential upside from the perspective of public debt consolidation. Such a dynamic would likely be accompanied by either a deep recession (requiring a big fiscal response) or by pressure on fiscal authorities to make up for less-effective monetary policy.” – bto: Ja, die guten Zeiten wurden nicht genutzt.

- “(…) leads us to our conclusion that if debt consolidation is going to happen in the coming decades, the bulk of the burden will need to be shouldered by monetary conditions, and we expect this would encompass both implicit and explicit pressure on central banks to provide the solution. (…) Any efforts to rein in primary balances will reduce short-term growth and lead central banks to adopt more accommodative monetary policy stances — and political pressure to keep rates low cannot be ruled out. Currency trends will redistribute demand in a way that creates winners and losers vis-à-vis public debt consolidation.” – bto: Natürlich spielt in diesem Umfeld die Handelsbilanz eine erhebliche Rolle. Weitere Möglichkeit für Deutschland, sich unbeliebt zu machen.

Und hier noch das Bild mit den Einzeldaten. Man sieht sehr schön, weshalb es in Deutschland so schön nach unten ging. In keinem Land lagen die Zinsen so deutlich unter der Wachstumsrate:

Quelle: JP Morgan

→ jpmorgan.com: “Dealing with the upward drift in government debt”