Demographics and markets: The effects of ageing

Bereits im März 2015 habe ich eine Studie der Bank für Internationalen Zahlungsausgleich zu den Wirkungen der demografischen Entwicklung an dieser Stelle besprochen. Darin kamen die Forscher zu dem Schluss, dass es keineswegs eine zwangsläufige Folge der (Über-)Alterung ist, dass es zu Deflation und tiefen Zinsen kommt. Im Gegenteil, die entscheidende Größe der Anteil der Abhängigen (unter 15 und über 65) wäre relativ zu den Erwerbstätigen. Jetzt käme eine Zeit, in der die Zahl wieder stiege, nachdem wir lange Zeit von weniger Kindern “profitiert” haben.

Hier nochmals der Link dazu:

→ Demografie ‒ Inflation oder Deflation als Folge alternder Gesellschaften?

sowie der zu einer guten Zusammenfassung aus der FINANZ und WIRTSCHAFT:

→ Demografie treibt bald Zinsen in die Höhe

Heute nun greift die FT eine neue Studie der US-Fed zu dem Thema auf und diskutiert die verschiedenen Szenarien sehr überzeugend:

- “The Federal Reserve (…) suspects that the world’s shifting demographics, as longer lifespans and reduced birth rates combine to increase the proportion of the aged within western societies, have rendered central banks powerless to raise long-term interest rates. That was the conclusion of a paper published this month.” – bto: Natürlich kann man das als einen weiteren Versuch der Notenbanken sehen, von der eigenen Verantwortung abzulenken.

- “Citing an example based on the changing age structure of the US population, they said: ‚The model suggests that low investment, low interest rates and low output growth are here to stay, suggesting that the US economy has entered a new normal.‘ (…) But there is an intense debate among investors and economists over how the pattern will play out.” – bto: Da ist etwas dran und gilt auch hier in Europa. Wenn die Erwerbsbevölkerung um 0,6 Prozent pro Jahr schrumpft und die Produktivität vielleicht mit 0,6 Prozent wächst, kommt null raus.

- “All agree that society’s choices over how they treat the old will go beyond the obvious moral and social implications, but could also determine whether deepening inequality can be reversed, and whether the world can escape from low yields and low growth.”

- “‚But demographics is not destiny. We need political courage to do this, and we need more of it.‘ Measures such as later retirement, incentives for carers and part-time workers and more immigration can all mitigate the effect of an ageing population.” – bto: Vor längerer Zeit zeigte ich schon, dass man damit zwar Zeit kaufen kann, den grundlegenden Trend jedoch nicht ändern.

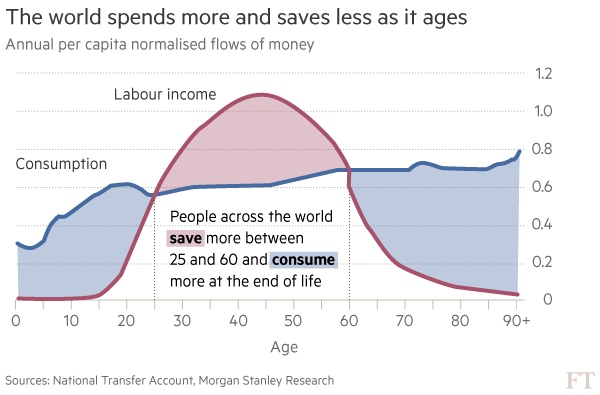

- “People save most during their working years. This prompts them to buy bonds either directly or mostly through pension contributions, pushing down yields. Then in retirement they consume more than they save — (…) This tends to push yields upwards.” – bto: Das leuchtet als Modell durchaus ein.

Quelle: Financial Times

- “When there is a bigger proportion of workers in the population, there is more competition for work. This pushes down labour’s negotiating power, and reduces both wages and inflation (…) investors will accept a lower yield from their bonds.” – bto: Das leuchtet ein und entspricht dem Ergebnis des bereits angesprochenen Papers der BIZ.

- “The new Fed paper suggests that ‚demographic factors alone account for a 1.25 percentage point decline in the natural rate of real interest and real gross domestic product growth since 1980‘. This is a huge claim, as it implies that demographics — rather than fiscal or monetary policy, technology or other changes in productivity — are responsible for virtually all of the decline in economic growth over the past 35 years.” – bto: Also wieder der Versuch, die eigene Schuld zu mindern. Ich denke, ohne das eifrige Zutun der Notenbanken wäre es nicht soweit gekommen.

Quelle: Financial Times

- “As this period also saw increased savings activity as baby boomers scurried to get ready for retirement, slow economic growth was accompanied by long bull markets in both stocks and bonds in the US. Thus the phenomenon of ageing baby boomers helped to explain rising inequality. Increasing asset prices raises the wealth of those who already have savings, while a lack of bargaining power kept wages down for the rest.” – bto: Dies ist eine gute Ergänzung zur Ursachenanalyse zum Thema Verteilung. Ich habe ja vor allem auf das Thema “Leverage” abgehoben.

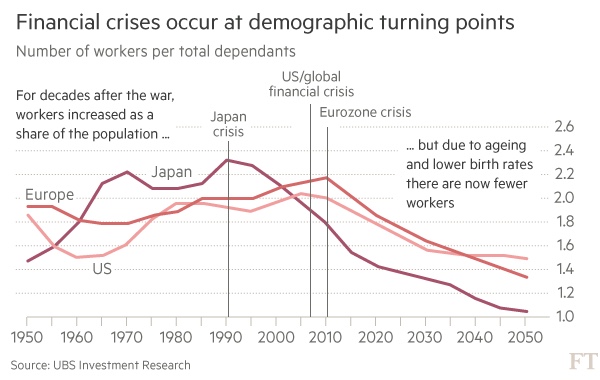

- “(…) the US, western Europe and Japan have all reached the ‚tipping point‘ when the numbers of people in work compared with old and young dependants has peaked and started to fall. In all three examples, that moment came just as the country suffered a major market crash.” – bto: Das ist ein Punkt, den man mal genauer untersuchen sollte.

- “The Fed economists warned of a ‚risk that permanent effects of demographic factors could be misinterpreted as persistent but ultimately transitory downward pressure on the natural rate of interest and net savings stemming from the global financial crisis‘.” – bto: Die Fed geht also davon aus, dass es so bleibt.

- “Their suggestion that the ‚scope to use conventional monetary policy to stimulate the economy during typical cyclical downturns is more limited than … in the past‘ makes deeply uncomfortable reading for central banks already throwing everything they have at obdurately low growth.” – bto: Es gibt aber noch weitere Gründe zur Sorge. Die Überschuldung ist keineswegs unter Kontrolle, geschweige denn bereinigt. Deshalb ist es sehr bedenklich, dass uns keine Instrumente mehr bleiben.

- “Last year, a team of economists at Morgan Stanley headed by Charles Goodhart, a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, argued that the rising number of retirees would ‚reverse three multi-decade trends‘ by reducing inequality, pushing up yields and raising equilibrium growth rates. ‚Both the young and the old are inflationary for the economy,‘ they said. ‚It is only the working age population that is deflationary.‘ With the working age population shrinking, inflation could return.” – bto: der Punkt der BIZ.

- “China’s rising population helped keep global growth going for the past two decades. Now, as the ‚one child‘ policy which was imposed in 1979 works its way through the age cohorts, there is an imminent demographic tipping point in China where the number of people aged between 15 and 64 peaked in 2013. That could mean less of a savings glut, and therefore less appetite to buy bonds — which will push up yields.” – bto: und übrigens auch weniger deflationären Druck aus China, weil die Löhne dort steigen. Allerdings ändert das vorerst nichts an den Überkapazitäten, die auf den Weltmarkt drücken.

- “Morgan Stanley faced withering criticism but the critical point at issue is the deal that society is prepared to offer the elderly. If they hold on to their current package, then rates could rise fast. But many believe that package is no longer viable and must be reduced.” – bto: Natürlich müssen die reduziert werden. Das Problem ist nur, dass die Alten die Wählermehrheit darstellen, siehe die Politik der Bundesregierung.

- “If the elderly are forced to accept a poorer deal, with later retirement ages and less help with healthcare and other costs, then rates could stay low and the economy stay trapped in a “new normal”. With an uncertain future ahead, workers would feel obliged to save at a greater rate while they were still employed. By working for longer, saving would continue for longer.” – bto: Ja, das ist die große Frage.

- “Joachim Fels, an economist at Pimco, responded with his own paper earlier this year entitled ‚70 is the new 65: demographics still support ‘lower interest rates for longer‘. Mr Fels said: ‚If you look at the data in more detail, people retire later and later in life and it’s those people who do the bulk of the savings who retire the latest. It’s the Warren Buffetts of the world, to take an extreme example. But there are many more people like that. (…) Dividing the US labour force by income, he showed that the participation in work by the top 20 per cent after the age of 65 had increased dramatically in the past two decades, and was likely to continue.‘” – bto: Das ist natürlich ein sehr interessanter Punkt, der auch bei uns zutreffen dürfte. Ich finde, das führt natürlich auch dazu, dass die ganze Ungleichheitsdebatte eventuell aus einem anderen Blickwinkel geführt werden muss.

- “All concede that broader cuts in what the state promises to pensioners are very difficult. As Mr Fels puts it: “Raising pension ages pushes down yields. The same argument applies to cutting payouts. Some call this ‘pension reforms’. Others call it ‘default’.”– bto: Natürlich ist es ein Default, wenn man finanzielle Versprechungen nicht erfüllt.

- “‚Capitalism rewards scarcity, and labour will become comparatively scarce,‘ warns (George Magnus), adding that low rates will not be a long-term phenomenon. ‚That will raise the return on labour relative to capital. That will turn into a redistributive mechanism within society. That won’t happen in the next 12 months, but it is a logical consequence, and does mean higher rates eventually.‘” – bto: Das leuchtet alles ein.

bto: Was in der Diskussion jedoch fehlt, ist der Gesamtkontext mit der Überschuldung von Staaten und Privaten. Schon in “Die Billionen-Schuldenbombe” und nun in der “Eiszeit” habe ich auf die fatale Kombination beider Faktoren hingewiesen: Zu hohe offene Schulden, unbezahlbare Versprechen und schwaches Wachstum werden zu einem explosiven Gemisch.

→ FT (Anmeldung erforderlich): “The 1890s and the end of the great bond bull market”, 25. Oktober 2016

Wenn man die UBS-Grafik auf China übertragen kann, dann müsste der demographische Wendepunkt 2013 doch in den nächsten Jahren dort zu einer Finanzkrise führen, oder? Wie sehen Sie das?

Ich sehe das genau so!

Wenn ich mir den chinesischen Immobienmarkt so ansehe, scheint sogar der Auslöser der kommenden Finanzkrise der gleiche wie in den USA zu werden…

>„‚But demographics is not destiny>

Das ist bullshit.

Wir müssen die demografische Entwicklung allerdings NICHT schicksalsergeben hinnehmen. Das ist etwas anderes.

>People across the world save more between 25 and 60 and consume more at the end of life>

Das ist richtig, wenn man das Mehr als prozentuales Mehr bezüglich des individuelle Einkommens versteht.

Bezogen auf die GESAMTNACHFRAGE stimmt das m. A. n. nicht.

Denn in einer alternden Gesellschaft fallen die Arbeitseinkommen trotz längerer Lebensarbeitszeit und wegen der speziell im Alter geringeren Einkommen wird von den Alten weniger konsumiert.

Heißt:

Die Nachfrage bleibt tendenziell niedrig, weil a) die Arbeitenden (unter 60, sagen wir) viel sparen und daher relativ wenig konsumieren und b) die nicht mehr Arbeitenden aufgrund geringen Einkommens zwar bezogen auf ihr Einkommen relativ viel konsumieren, was aber bei geringen Altersbezügen wenig ist.

Ich glaube auch, dass Arbeit nicht TROTZ abnehmender Nachfrage, sondern WEGEN Knappheit an Arbeitskräften im leistungsfähigsten Alter (sagen wir unter 60) teurer wird.

Damit wir des Inflation geben, die m. A. n. durch die unvermeidlichen Verteilungskämpfe verstärkt werden wird. Damit werden auch die Zinsen steigen. Das hat mit dem Kauf von Bonds erst einmal nichts zu tun.

Die Gesellschaft wird den Alten keinen „Deal“ anbieten, sondern was es geben wird, ist Verteilung, die durch Konflikte bestimmt wird: Die Alten in der Mehrheit (heute schon) und daher in Demokratien die Politik dominierend. Die Jungen haben dagegen den Zugriff über das BIP: Wenn sie nicht genug davon bekommen, werden sie Arbeit verweigern bzw. auswandern.

Auf allem obendrauf:

>Zu hohe offene Schulden, unbezahlbare Versprechen und schwaches Wachstum werden zu einem explosiven Gemisch.>

… das sich spätestens dann entzündet, wenn sich die Ersparnisse (= Ansprüche an das BIP) in Luft auflösen.