FT warnt vor einem “Doomsday Szenario” für den US-Dollar

“Und das in der FT!” schrieb mir ein Leser und brachte damit den Gedanken auf den Punkt, den ich auch hatte, als ich die (FINANCIAL TIMES) FT – meines Erachtens eine der, wenn nicht gar die beste Zeitung der Welt – in Händen hielt. Nun weiß ich, dass der Abgesang auf den Dollar immer dann erfolgt, wenn eine echte Rallye noch bevorsteht und zum anderen, dass auch die FT von Zeit zur Zeit exotische Artikel bringt, damit die Journalisten bei der nächsten Krise schreiben können, sie hätten ja auch gewarnt. So war es zumindest 2009.

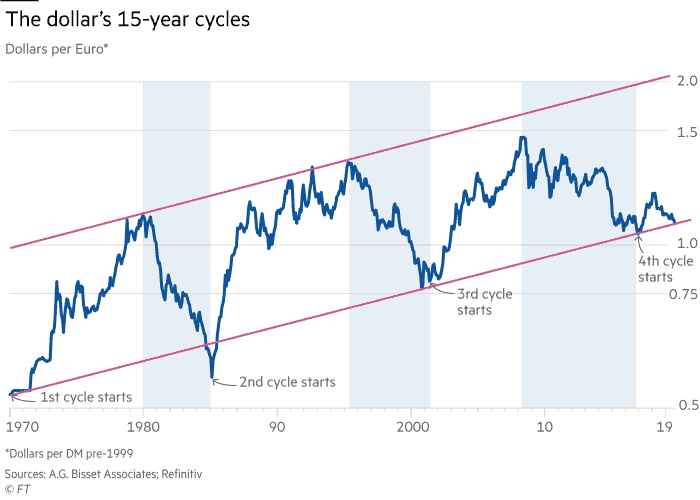

Doch kommen wir zu der durchaus überraschenden Nachricht, die übrigens auf einer Analyse beruht, die ich hier schon vor ein paar Wochen hatte: → Steigt der Euro auf 2:1 zum Dollar?

Was uns aber nicht hindern sollte, die Argumentation zu beleuchten:

- “For decades, global savers, and American retirement savers in particular, have been taught that you should put most of your money in an S&P index fund — one that tracked the fortunes of the largest US companies — and then forget about it until you were close to retirement. (…) American multinationals were, after all, the best way to buy into globalisation, and globalisation was very good for the stock prices of many big companies. But recently, I’ve begun to wonder — what would it mean if the entire paradigm for long-term investing was to change?” – bto: einfach deshalb, weil es eben nur ein Zeitausschnitt war, vor allem einer mit einer außergewöhnlichen Kombination von Faktoren. Freie Schaffung von Geld (Abkehr von der Goldbindung), explodierendes Arbeitskräfteangebot (China, Osteuropa), asymmetrische Notenbankpolitik.

- “America’s place in the world has changed, and so has the growth potential of its corporations. If that is the case, then we may be in for a correction not just in the stock prices of US multinationals, but in the dollar itself. (…) It’s a scenario that AG Bisset Associates has dubbed ‘the Doomsday Dollar’. At first glance, the idea of US stocks and the dollar going down at the same time seems unlikely. For one thing, the two often go in opposite directions, with a weak dollar making the exports of many US companies relatively more competitive in the global marketplace, as has been the case in recent years.” – bto: Dies spricht tatsächlich gegen ein solches Szenario.

- “Currency movements can happen more quickly — in fact, (…) the world’s major currencies tend to move up and down in 15-year cycles. According to his calculations, which track currency movements from the early 1970s onwards, we began a new cycle in January 2017, and despite the dollar’s strength since April 2018, that cycle is still intact. If the thesis holds, the dollar is poised to fall against the euro and yen over the next few years, and by as much as 50 to 60 per cent.” – bto: Dazu bringt dann die FT eine schönere Version des Charts, das ich schon in dem oben zitierten Beitrag hatte:

Quelle: FT

- “(…) investors outside the US, like European and Japanese pension funds, the family offices that manage the finances of wealthy individuals, and large financial institutions, would be hit hard by depreciating dollar assets. If they began to shift their investment portfolios away from dollar assets, it could exacerbate a downturn in US equities — this is something that many analysts believe is coming anyway, given that stocks are at their second most expensive period in 150 years. That would, in turn, hurt US savers who keep the majority of their retirement portfolios in those S&P index funds.” – bto: Es würde alle treffen, wenn die letzte Bastion des Vermögenserhalts kippt.

- “Some savvy investors already see the writing on the wall and have moved into gold. I would expect other commodities to rise, too. If the ‘Doomsday’ scenario plays out, investors might also pile into the euro and the yen, which would force US bond yields to rise. That is something that few expect — the conventional wisdom is that we are in an environment of low rates forever.” – bto: Es ist schwer vorstellbar, dass wir steigende Zinsen haben, ohne den ultimativen Margin Call auszulösen. Doch das wäre ein deflationärer Kollaps, der wohl kaum mit einem starken Euro einhergehen kann. Außer als kurzer Vorläufer vor dem Kollaps des Euro, der das nämlich nicht überleben würde.

- “But if yields were to rise, it could help savers who are holding bonds rather than stocks — it would also, however, penalise debt-ridden companies. And (…) there are plenty of ‘zombie’ firms out there that will have trouble servicing their debt and staying in business if rates rise. Over the past few decades, we’ve seen not only a bull market for US equities, but plenty of financial engineering. Companies have done what they could to defy economic gravity using everything from the tax code to share buybacks. Central bankers have facilitated this with loose monetary policy. That is why, in my opinion, both US stocks and dollar-denominated asset prices have remained so high, despite so many risk factors in the political economy, and the challenges for business.” – bto: Zunächst werden die Bondholder keine Gewinner sein. Denn Pleiten von BBB und schlechter werden zu Verlusten führen. Steigende Zinsen bedeuten auch Kursverluste auf Anleihen im Bestand. Erst danach wären Bondholder besser dran, aber dies wohl auch nur nominal, da es weiterhin finanzielle Repression geben wird. Siehe Studie der Deutschen Bank, besprochen letzte Woche an dieser Stelle.

- “Ultimately, if US companies are perceived as no longer being the most competitive in the world, their share price will fall, as will the dollar. Are we at that point? Not yet. But given the erosion of America’s skills base, its ailing infrastructure and lack of research investment, I wonder if we might be soon. Companies themselves seem to be voting with their feet. A recent EY report shows that the number of Fortune Global 500 companies headquartered in the US declined from 179 in 2000 to 121, while the number headquartered in China grew from 10 to 119. This signals a shift in where companies expect growth to come from in the future — Asia. If that is the case, many of us will need a new investment strategy for a new world.” – bto: Von Europa oder gar Deutschland ist da schon gar nicht mehr die Rede. Für mich war schon immer klar, dass wir uns mehr nach Asien ausrichten müssen. Das ist nicht gefahrlos, aber die einzige langfristig richtige Lösung. Ein Anfang ist, sich bei der Allokation nicht mehr am MSCI World auszurichten, sondern am Anteil am Welt-BIP. Damit hat man schon heute mehr Asien dabei.