Chinas Schuldenboom ist keine Neuigkeit

Die Studie „The History and Future of Debt“ der Deutschen Bank ist ein wahrer Fundus. Wir haben die Schlussfolgerungen bezüglich der weiteren Politik in den westlichen Ländern („Helikopter“) schon besprochen. Nun geht es um China. Ich habe immer wieder auf die Gefahren der dortigen Entwicklung hingewiesen. Ich erinnere an:

→ China: Schuldenwirtschaft nach westlichem Vorbild

Die Gefahr ist eindeutig, wie die Zahlen zeigen:

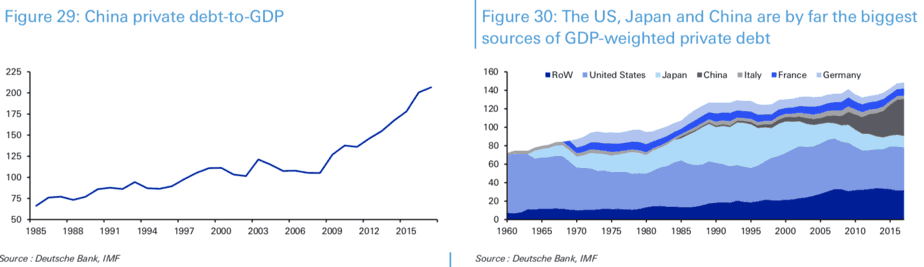

- „China has been a substantial marginal debt contributor to the global debt pie since the GFC, especially in the private sector (…). As growth slowed during the GFC, China opened the spigots to try to prop up global demand while the RoW recovered. This was probably meant to be a temporary phenomenon, but DM growth struggled to return to its pre-crisis levels and it was difficult for China to reverse course. This has led to the private debt/GDP ratio rising from c.105% in 2008 to 207% in 2018. Without China, global private sector debt would have dropped notably since the GFC. However, would global GDP growth have been much slower without it?“ – bto: Zweifellos, würde ich sagen. Letztlich hat China beim Deleveraging des westlichen Privatsektors geholfen und steht auch hinter dem Rückgang der Schulden in Deutschland.

Wie groß der Effekt Chinas war, zeigen diese Abbildungen:

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

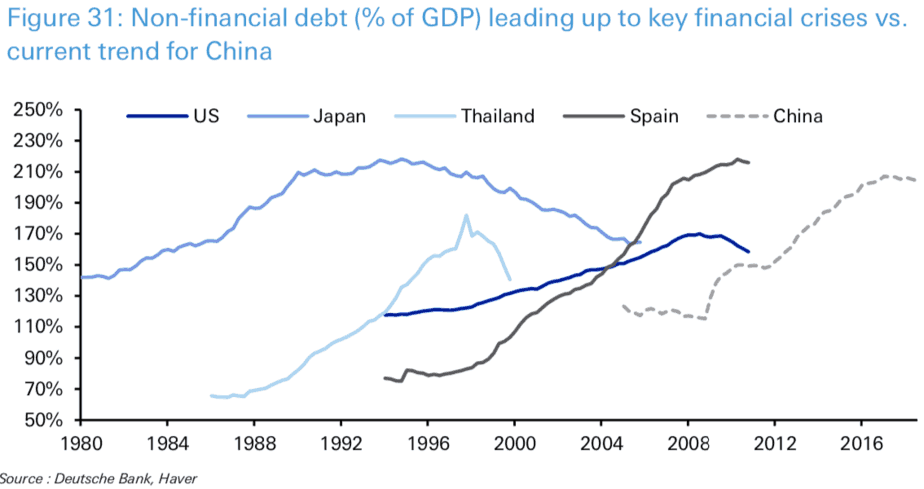

- Dann machen die Analysten den wohl entscheidenden Vergleich. Immer, wenn Schulden besonders schnell wachsen, ist die Gefahr von Fehlinvestitionen besonders groß. Die Abbildung vergleicht „(…) this debt accumulation against some countries that have previously seen private sector debt boom/bust cycles. At this stage, it’s not clear whether China can avoid the fate that has eventually created a credit crisis in these countries, but the rapid credit growth deserves close monitoring. On the negative side, it’s widely appreciated that a lot of this debt funds unprofitable SOEs with the risks of zombie status prevalent alongside decreasing productivity. On the other hand, the state has control over its economy and the debt is not as exposed to investor flight as other markets that have gone through debt crises.“ – bto: Das wirft dennoch die Frage auf, wie sich das Problem dann bemerkbar macht. Denn man kann doch nicht davon ausgehen, dass es sich ewig unterdrücken lässt. So oder so ist die Abbildung spannend, wobei Korea in der Darstellung leider fehlt. Dort war es ähnlich:

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

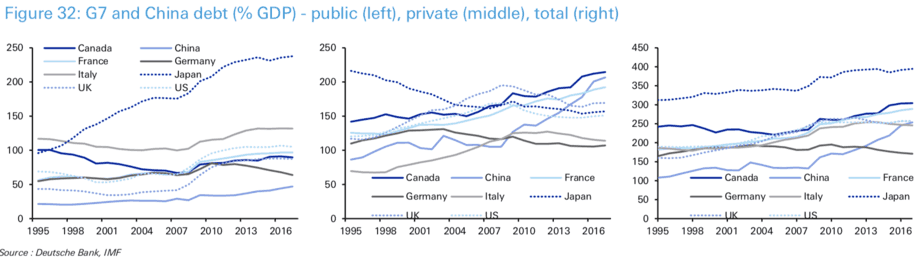

„This rise in debt rightly appears alarming but one could say that in aggregate, China’s total economy-wide debt/GDP is actually at the lower end of the G7 range with only Germany and Canada at lower levels. So within a relatively closed economy, it would seem that China could in theory control any private sector credit crisis. There is scope for government debt (currently 47% of GDP) to increase before it is at similar levels to that of its G7 peers.“ – bto: Natürlich kann China die verdeckte Staatsschuld (bei SOEs) in offizielle Staatsschulden wandeln. Andererseits dürfen wir nicht vergessen, dass auch China vor einem spürbaren Rückgang der Erwerbsbevölkerung steht. Dieser hat wie schon in Japan und zunehmend bei uns entsprechend negative Wirkungen auf Wachstum und Schuldentragfähigkeit.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank