Steigende Zinsen sind Gift für Assetpreise

Gestern habe ich das Szenario steigender Zinsen als Folge höherer Inflationsraten diskutiert. Doch wie wirken steigende Zinsen auf die Kapitalmärkte? Schlecht – lautet die kurze Antwort. Die lange (und bessere) ist fundierter und zeigt an der sogenannten “Duration” die Sensitivität. Die Experten von GMO – immer wieder bei bto zitiert, u. a. hier

→ „Quantifying the Fed’s Impact on the S&P 500“ – erheblich

→ Staatsschulden – wirklich so schlecht?

→ Maue Renditen mit allen Assets – im besten Fall

→ „Der Aktienmarkt ist abscheulich teuer“

haben ausgerechnet, wie stark die Preise verschiedener Assets vom Zins getrieben werden. Ergebnis: Alle Finanzassets sind zur “Perfektion” gepriced. Es gibt nicht mehr viel Luft nach oben.

Hier die Studie, die schon im August 2016 hier zitiert habe:

- “We believe further that it is important to realize that the strong returns to the assets that have done well over the last seven years are at best a one-off benefit and, more plausibly, will have to be given back over time. To us, this suggests that while alternatives have been a drag on institutional portfolios over the last six or seven years and privates (real estate, private equity, venture capital) have been a boost, in coming years the reverse may well be true.” – bto: Die Gewinne sind also nichts anderes als Vorwegnahmen künftiger Erträge, wie hier immer wieder betont.

- “The assets that have done well do not necessarily share that much in common, but they do all share a structure that they embody at least somewhat predict able cash flows that will occur over an extended period of time. The value of those cash flows changes materially if the discount rate applied to those cash flows changes.” – bto: Das ist der entscheidende Punkt! Stabile Cashflows werden gekauft und deshalb immer teurer.

- “(…) all of these assets can readily be valued through a discounted cash flow process, and the sensitivity of the present value to a change in the discount rate is precisely analogous to the duration of a fixed income security.” – bto: Es ist nichts anderes als ein abgezinster künftiger Ertrag, wo der Abzinsungssatz immer tiefer wird.

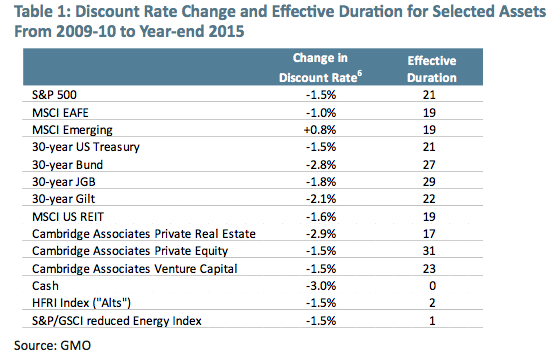

- “Table 1 shows an estimate of the change in the discount rate from a 2009-10 average to year end 2015 along with the effective duration of the asset class with regard to that change:” – bto: Das zeigt ganz klar, wie sehr die Zinsen verzerrend wirken.

- “(…) the striking discrepancy is between the first 11 asset classes and the last 3. For any asset with a long duration, the discount rate fall has been a decided positive for returns for the asset class. But for short duration assets, it has actually been a negative. This occurs because there are two sides to the fall in discount rates. It increases the present value of distant cash flows, but it also decreases the current income available on the asset. The negative side of this is simplest to think about in the case of cash. Cash is the purest short duration asset. If cash rates fall, there is no capital gain to enjoy, but the income earned in subsequent periods will be reduced.” – bto: Das gilt allerdings umgekehrt auch, was Cash dann attraktiver macht. Also vermutlich für 2018.

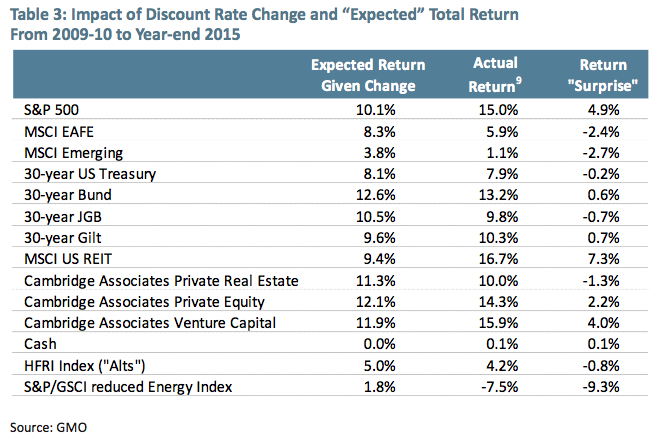

- Sodann vergleicht GMO den aus dem Fall des Diskontsatzes erwarteten Return mit dem tatsächlichen Return der Assets:

- “REITs have done surprisingly well behind pretty strong FFO (funds from operations) growth, the S&P 500 has done surprisingly well behind good earnings growth, and commodities have done impressively badly as boom turned to epic bust.” – bto: was daran liegt, dass REITs einen stabilen Cashflow versprechen.

- “In general, there has not been a particularly apparent rush into long-duration fixed income despite the strong returns, because the simple math of bonds is such that most investors realize intuitively that falling bond yields are a negative for future returns.” – bto: weil sie natürlich das Konzept des discounted Cashflows verstehen.

- “(…) the trouble with returns that come from falling discount rates is that they represent an increase in the present value of the asset without any increase to the cash flows to the asset class. The future expected return to the asset has fallen, and in a way that more or less precisely counteracts the increase in current value. In other words, the present value of the assets has risen but the future value of the assets has not.” – bto: Die Zukunft ist also heute schon da!

- “Let’s say that you will need, with absolute certainty, $1 million in 2026. The safest way to reach that goal is to buy a $1 million face value 10-year zero coupon Treasury bond maturing in 2026. Such a bond currently has a yield of 1.625%, which means it will cost you $851,127 to buy it today. Assume that tomorrow the yield falls by 1% to 0.625%. Your brokerage statement will declare the value of your bond to be $939,596, a gain of over $88,000.” – bto: Das ist aber nur ein Buchgewinn!

- “You’ve just made over half of the necessary return over the next 10 years in a single day. But the value of that bond in 2026 has not changed at all. It has a fixed maturity value of $1 million. The only thing that has changed is the discount rate being applied to that cash flow, not the cash flow itself. Assuming you still need $1 million in 2026, there is no windfall to spend. Economically, nothing has changed for you, whatever your brokerage statement says.” – bto: Dennoch dürften die Gebühren steigen, man ist ja jetzt “reicher”. Übrigens noch ein Punkt in unserer Vermögensdebatte.

- “(…) the fact that the valuation of US equities has risen guarantees that the future returns to US equities from here will be lower than they would have been otherwise, and the same is true for all of the long-duration assets whose discount rates have fallen over the period.” – bto: Und es geht genauso in die andere Richtung.

Spannend ist natürlich die Frage, was passiert, wenn die Zinsen wieder steigen sollten. Die Erkenntnisse von GMO kann man dann eigentlich nur so übersetzen: Es darf schlichtweg nicht passieren!

- “The most shocking hole that will be blown through people’s portfolios is if discount rates rise again fairly quickly. Even if the circumstance is one in which the global economy is doing well, the impact of a 1.5% increase in the discount rate on equities from here is a fall of over 30%, which would almost certainly be enough to swamp the earnings impact of the decent growth.” – bto: Die Annahme dürfte nicht falsch sein, dass in diesem Szenario die Assetpreise nach unten überschießen!

- “For a portfolio that is fully invested in long-duration assets (i. e., consists of a combination of stocks, bonds, real estate, and private equity), the possible performance implication is on the order of the falls experienced in the financial crisis – perhaps a 20-33% fall depending on the weightings – despite the fact that the global economy was doing just fine.” – bto: so viel zum Thema “sichere Assets”.

- “So what can we do to protect portfolios against this possibility? One answer would be to hold cash, which, as a zero-duration asset, would be a beneficiary of rising discount rates. The trouble with cash, of course, is that if the discount rates do not rise, it is doomed to deliver little or nothing.” – bto: Ich würde es dennoch jedem empfehlen. Cash ist ein super Investment.

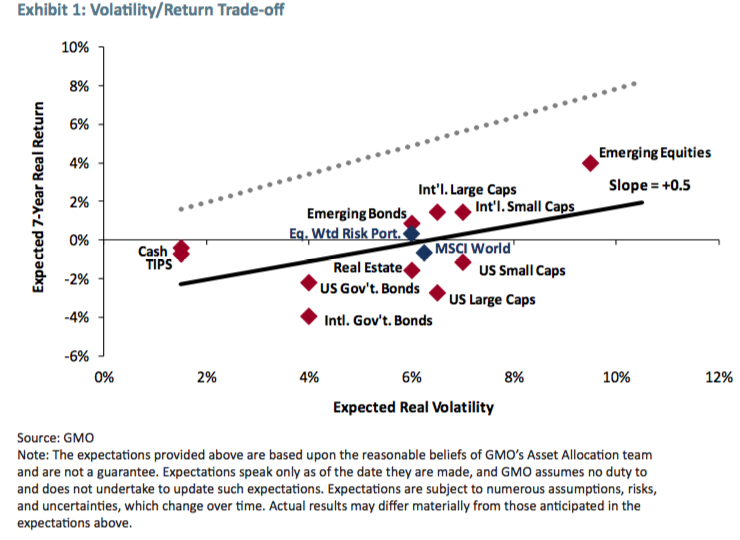

- “Today does not look like a great opportunity to reach for risk, despite the temptation in the face of unprecedentedly unattractive yields on government debt.Exhibit 1 shows a simple way of looking at the risk/reward trade-off available to investors today. It takes our seven-year forecasts for asset classes and plots the expected returns against expected volatilities for the assets.”

- “This tells us the general relationship between volatility and return available today. The slope of the line at equilibrium would be about 0.7. Today it is 0.5, although arguably even that flatters the attractiveness of risk assets because a fair bit of the slope comes from the extremely unattractive returns on offer from non-US government bonds, which today have an average yield of 0.16%, and most of the rest comes from emerging equities, which happens to be both the cheapest and most volatile asset of the group.” – bto: Die Idee, in Emerging Markets zu investieren, dürfte so blöd nicht sein.

- “The most striking thing about the chart is how low the regression line is on the page. The dotted line above shows what the line would look like at equilibrium. While it is true that today’s slope is somewhat flatter than normal, the striking difference is how much lower the line is on the page than equilibrium – four to five percentage points lower!” – bto: was übersetzt nochmals zeigt, wie stark alles überbewertet ist.

“If the shift is permanent – the ‚Hell‘ scenario we’ve written of before (bto: Eiszeit!) – returns will be lower to all assets for which the discount rate has fallen, but at least the windfall gains will have to be repaid only very slowly. If the shift is temporary, we will wind up giving back the windfalls of the last six to seven years. The temporary shift scenario is better for investors in the long run, but it would be massively painful in the interim, because it will affect almost every asset in most investors’ portfolios.”

Klartext: Wenn die Zinsen steigen, haben wir ein massives Problem.