Das Produktivitätswunder kommt doch

Bekanntlich sind neben der Überschuldung und der Entwicklung der Erwerbsbevölkerung die geringen Produktivitätszuwächse einer der wesentlichen Gründe für die „Eiszeit-These“. Und hier herrscht der Streit: Messen wir nicht richtig oder steht der große Schub unmittelbar bevor oder liegen die besten Zeiten wirklich hinter uns? Die Antwort dürfte entscheidend sein für den Ausblick für Weltwirtschaft und Kapitalmärkte.

In einem Beitrag greifen Matthew Tracey und Joachim Fels das Thema interessant auf:

- “If robust productivity growth were indeed a relic of the past, the long-term consequences for investors would be profound: Lower-for-even-longer interest rates would prolong the pain for yield-starved savers, pension funds and financial institutions; equity markets might underwhelm in a low-growth world (…).” – bto: unser Eiszeitszenario.

- “The productivity question couldn’t be more important. After all, there are only two ways to grow an economy: boost productivity, or grow the labor force (demographics).” – bto: Wie immer wieder an dieser Stelle erwähnt, dürfte Zuwanderung nur den Ländern helfen, denen es gelingt, die globalen Talente anzuziehen. Länder hingegen, die ungesteuerte Zuwanderung zulassen und gar fördern, schaffen sich eine erhebliche zusätzliche Belastung und werden dadurch noch unattraktiver für die globalen Talente.

- “Fortunately, the upside potential for global productivity is growing (…) Our thesis in a nutshell: Don’t rule out a global productivity rebound in the coming years that ushers in “old normal” (4 %+) global growth.” – bto: Das wäre fantastisch, würde es doch den Umgang mit Schulden und Alterung erleichtern.

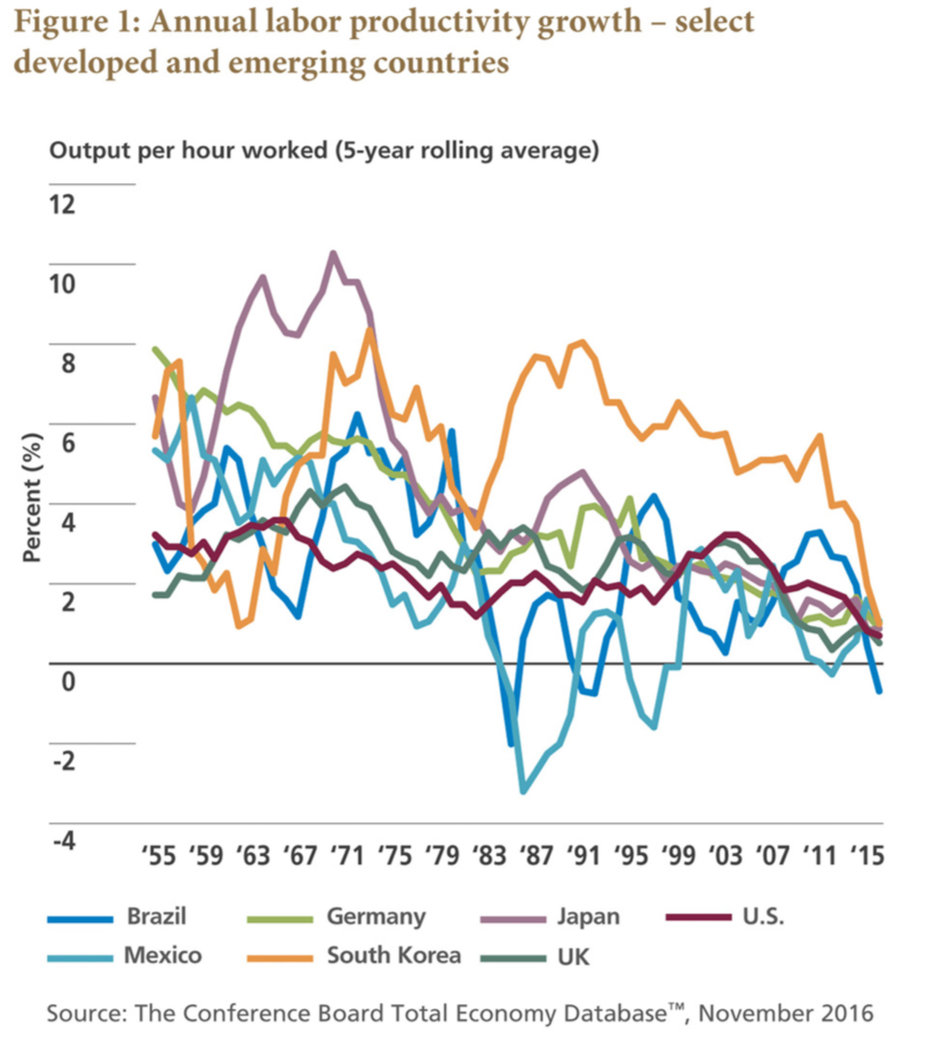

- “Labor productivity – or GDP per human hour worked – is in the dumps. Throughout the entire post-financial-crisis period we’ve observed declining productivity growth in economically significant countries worldwide.” – bto: was auch mit der Krise zu tun hat, vor allem der verhinderten Bereinigung von Überkapazitäten.

- “‚Demand-side‘ secular stagnation devotees, notably Larry, suggest that a chronic deficiency of aggregate demand and investment is responsible for the dismal productivity growth we’ve seen in recent years (…). Meanwhile, ‚supply-side‘ secular stagnationists such as Robert Gordon believe innovation today isn’t what it used to be and that (…) nothing (is) on the horizon that will rival the breakthroughs of the past.” – bto: Beides kann und muss man natürlich kritisch sehen. Es gibt ja doch Innovationen am Horizont, die deutlichen Einfluss auf viele Industrien haben werden.

- So sehen das auch die ‚techno-optimists‘: “(…) people who argue we’re on the cusp of radical breakthroughs that will drive huge gains in productivity and living standards.” – bto: was eben nicht auszuschließen ist. Profitieren dürften davon aber vor allem Länder mit sehr gut gebildeter Bevölkerung bzw. Zuwanderern.

- “A handful of technologies have emerged that are radically changing the way firms do business. These technologies – offspring of the computer revolution – include artificial intelligence (advanced robotics), simulation, the cloud, additive manufacturing (3D printing), augmented reality, big data, microsensors and the “internet of things” (web connectivity of everyday objects). These technologies are now being used, in many cases for the first time, in synergy with one another. Together, they enable businesses to experiment more effectively, better measure their activities in real time, and scale their innovations – and those of their peers – faster.” – bto: Aus meiner Arbeit mit Technologie-Start-ups kann ich diese Einschätzung nur teilen. Meine Sorge ist, dass wir gerade in Deutschland den Wandel unterschätzen.

- “Smarter experimentation plus faster scalability of winning ideas can speed up the diffusion of best practices from productivity leaders to laggards. And global ‚catch-up‘ potential is huge, especially in emerging markets (EM). The productivity gap between leading, ‚frontier‘ firms and all others has widened dramatically in recent years.” – bto: Dieser Gedanke hat etwas. Es könnte aber auch sein, dass es zu viele “The winner takes it all”-Geschäftsmodelle sind, die eben nicht zu dem Verbreitungseffekt führen, sondern zur tendenziellen Monopolisierung.

- “Haven’t computers, the internet and automation been around for years? Why should we expect a productivity rebound anytime soon? One key reason: cost. Productivity-enhancing technologies exist today that haven’t yet been put to use because their cost outweighs their perceived economic benefits. That’s changing.” – bto: Das stimmt sicherlich.

- “McKinsey & Company (…) offered projections of global sector-level productivity growth potential through 2025 based on anticipated diffusion of known technologies and existing best practices. (…) Agriculture: 4%–5% (…), Automotive: 5%–6% (…) Food processing: 3% (…) Healthcare: 2%–3% (…) Retail: 3%–4% (…).” – bto: Und das deckt sich mit meiner persönlichen Erfahrung.

- “McKinsey forecasts 4% potential annual productivity growth through 2025 – a jolt higher from the 2%–2.5% post-financial-crisis global average. (…) This 4% forecast is based only on the diffusion of existing best practices and known technologies – i.e., before giving any credit to unknowable future innovations. As the study suggests, “Waves of innovation may, in reality, push the frontier far further than we can ascertain based on the current evidence.” – bto: Das halte ich ebenfalls für denkbar. Wenn es so käme, wäre das wirklich eine Erleichterung, aber keine Lösung.

- “(…) we envision three possible scenarios for global productivity. The first is that our weak-productivity status quo – call it secular stagnation – persists. (…) The future effect of secular stagnation on interest rates is ambiguous – though we note that a continued global trend toward populism (…) could put a higher inflation term premium in nominal yield curves (causing curves to steepen).” – bto: Es ist eigentlich keine „Inflationsprämie“, sondern eine Risikoprämie für Gläubigerenteignung.

- “The other two (more optimistic) scenarios both involve a productivity rebound; (…) Either innovation reduces required inputs for a given output (through efficiencies and cost savings), or innovation boosts output for a given input.” – bto: Das dürfte von entscheidender Bedeutung sein für die politische Stabilität und wiederum für die Bewältigung von Schulden und Alterung.

- “Consider the potential long-term economic and market impact of ‚Technological Unemployment‘: Global GDP growth picks up moderately, Inflation remains low and stable, Labor market distortions and inequality worsen; chronic underemployment develops, Global interest rates rise modestly from rock-bottom levels, Yield curves modestly steepen, but only if growth impulse more than offsets disinflation impulse; otherwise, curves could flatten, Equity markets perform well given improving economic growth, muted inflation, and rising corporate profitability.” – bto: Das ist ein konsistentes Szenario, allerdings eines, das ich für höchst instabil halten würde.

- “The distribution of wealth across society could well become even more uneven given rising polarization between the ‚capital owners‘ and everyone else.” – bto: So kann man es wohl sagen!

- “Our ‚Productivity Virtuous Circle‘ scenario involves a different (and better!) type of productivity growth – one where innovation drives productivity gains without rendering human workers redundant. Here’s how. First, new technologies and processes employed in one industry generate cost savings and efficiencies in that industry. But they also create new jobs – jobs that require new skills we didn’t yet know we needed. A virtuous circle then develops: Technological growth in one industry forces related industries to innovate (or fall behind), creating even more demand for new skills. And on we go. The upshot: In this scenario there is no mass of discouraged (former) workers plodding off to the beach. Mechanically, productivity gains are driven mostly by a rising numerator (output) rather than by a falling denominator (hours worked).” – bto: was voraussetzt, dass die Menschen so gut qualifiziert sind, dass sie die neue Aufgabe wahrnehmen können.

- Das würde dann diese Folgen haben: “Global GDP growth approaches ‚old normal‘ levels (4%+) in an enduring escape from secular stagnation, Inflation normalizes but remains well-contained, Labor markets strengthen, Global interest rates rise given strong economic growth, Yield curves bear-steepen, Equity markets perform well (…).” – bto: Soso, Aktien steigen also in jedem Szenario. Davon bin ich nicht überzeugt.

Bottom line: productivity’s upside risks are growing

- “(…) we see a growing risk that we collectively underestimate the global economy’s pent-up productivity potential. (…) don’t count out a ‚Productivity Virtuous Circle‘, which – lest we forget – is not lacking in historical precedent. The Luddites of 19th century England and their ilk have been wrong for two centuries; historically, over long periods of time, technological change has been a net creator of higher-skill jobs – and has not jeopardized full employment.” – bto: Das ist in der Tat die große Hoffnung. Was mir Sorgen macht, ist der Zustrom unqualifizierter Menschen, die in dieser neuen Welt kein Platz finden könnten.

- “There may also be a nascent macro catalyst at play. Global central banks are beginning to rein in extraordinary post-financial-crisis monetary stimulus, which (…) probably has for years distorted the allocation of capital worldwide. The withdrawal of ultra-accommodative monetary policy may encourage a more efficient capital allocation throughout the global economy, potentially helping jumpstart creative destruction – the key to shrinking today’s massive productivity gaps.” – bto: weil die Notenbanken die Zombies nicht mehr schützen. Leuchtet sicherlich ein.

- “A productivity rebound could mean higher interest rates and steeper yield curves – greener pastures, indeed, for savers, pension funds and financial institutions. It could mean equity investors wouldn’t be doomed to a stagnant future of low returns. And it could boost the resilience of the global economy in the face of several looming secular risks. Productivity’s right tail is getting fatter; if history is any guide, the night often appears darkest just before dawn.” – bto: Ich finde, diese interessante Überlegung kann man nicht von der Hand weisen. Vielleicht gibt es ja doch eine Überwindung der Eiszeit?

Den ‚Productivity Virtuous Circle‘ halte ich für naives Wunschdenken (oder gar neoliberale Propaganda). Als Beispiel die absehbare Automatisierung des Straßenverkehrs: Millionen Fahrer werden arbeitslos werden, aber die (viel wenigeren) Jobs, die es dafür braucht, gibt es schon seit Jahren, und mit dem Erfolg werden auch sie überflüssig. Die Automatisierer (Informatiker) finden sicher Arbeit in weiteren Automatisierungsprojekten (vielleicht das Ersetzen von Bänkern oder Juristen), aber was machen die Fahrer? “Der Markt” wird sie nicht brauchen. Wenn wir unser System nicht grundlegend ändern, rutschen wir in eine soziale Katastrophe.

Mir ist bei dem Gedanken nicht wohl, aber wenn jedes Land nur die exzellent ausgebildeten Zuwanderer oder alternativ eben gar keine haben will, werden wir in Zeiten digitaler Medien wohl mehrere hundert Millionen Leute unterwegs haben, die erst einmal unseren Produktivitätsstandard erreichen wollen und die niemand haben will. Solange dieses Problem nicht gelöst wird, dürfte es schwierig werden, die Produktivitätssteigerung für etwas anderes als Grenzschutz, Polizei, Militär und Soziales auszugeben. Die exzellente Ausbildung organisiert sich leider nirgendwo alleine. Nur gibt es sie in vielen Ländern gar nicht oder nur für die Kinder der Oberschicht.

Hier die optimistische Einschätzung des IWF:

,Der IWF rechnet trotz Unsicherheiten über die US-Finanzpolitik mit einer Beschleunigung des globalen Wachstums.’

https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article166939499/Die-Welt-steht-vor-dem-groessten-Aufschwung-des-Jahrzehnts.html

Ist das Wunschdenken?

,Es zeichnet sich ab, dass Europa ein Treiber der Weltkonjunktur sein wird.’