Exportweltmeister ohne Gewinn

In meinem kommenden Podcast (8. August 2021) ist Moritz Schularick mein Gast. Er forscht und lehrt am Institut für Makroökonomik und Ökonometrie der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn. In seiner Forschung beschäftigt sich Schularick mit der monetären Makroökonomik, der internationalen Ökonomik und der Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Seine Studien zu den Ursachen von Finanzkrisen und zur Transformation des Finanzsystems gehören zu den international meistzitierten makroökonomischen Aufsätzen des letzten Jahrzehnts.

Grund genug für mich einige seiner Studien, die bei bto in der Vergangenheit bereits vorgestellt wurden, erneut zu diskutieren. Heute eine Studie zu den Erträgen unseres Auslandsvermögens:

Ein Team von Ökonomen hat sich den Erfolg der deutschen Kapitalanlage im Ausland gründlich angeschaut. Wer es gern dynamisch erklärt haben möchte, dem empfehle ich die Aufnahme der Präsentation von Professor Schularick – einem der Autoren – im ifo Institut.

Die Studie kann man auch nachlesen: → EXPORTWELTMEISTER: THE LOW RETURNS ON GERMANY’S CAPITAL EXPORTS

Es lohnt sich, die Studie zu lesen, wenn man bereit ist, sich mit einer der prominentesten Ursachen für unser geringes Vermögen – Stichwort „Märchen vom reichen Land“ – zu beschäftigen. Zunächst die Feststellung: Die Dimensionen sind gigantisch!

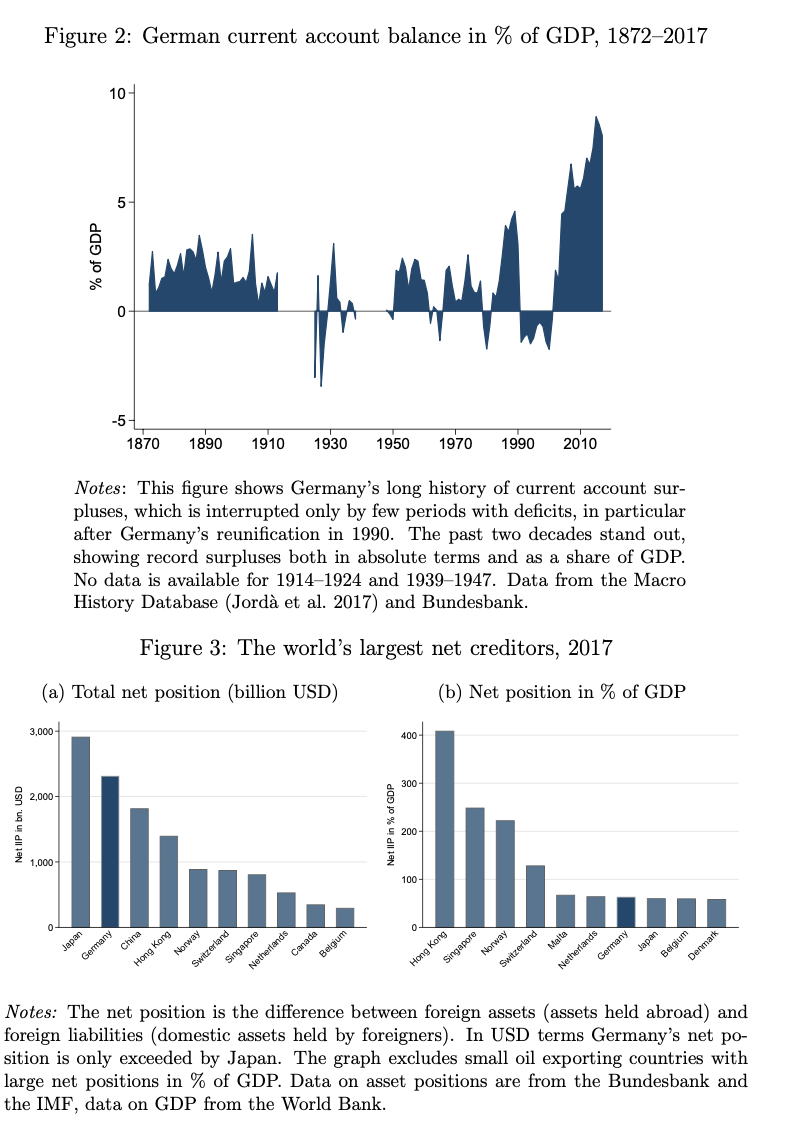

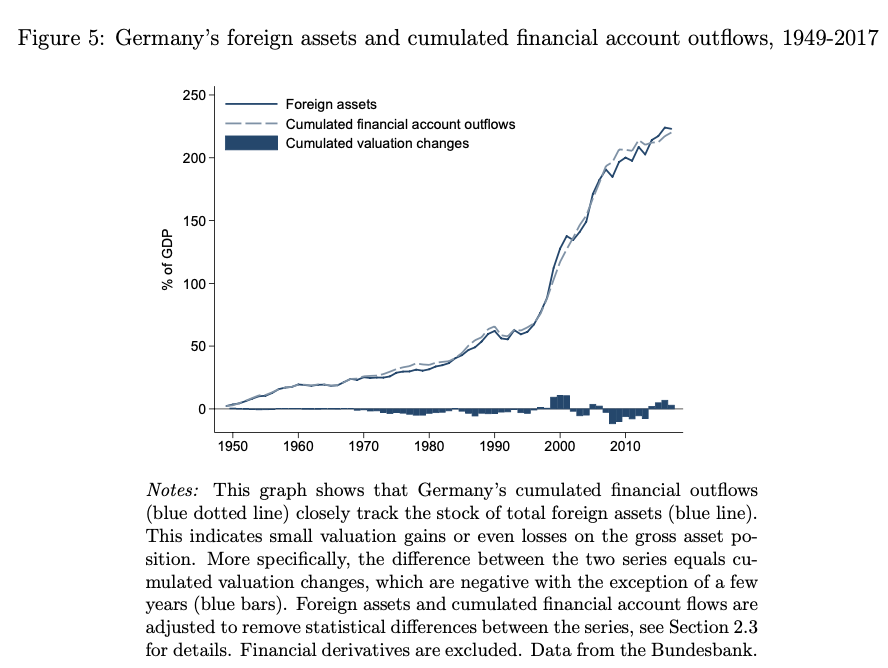

- “(…) the last decade is characterized by exceptionally high surpluses, even by historical standards. The recent surpluses were about three times higher relative to GDP than in gold standard times and during the so-called economic miracle in the 1950s and 1960s. As a result of consistently high capital exports, Germany ranks among the worlds top external creditors, both in absolute numbers and relative to GDP, as Figure 3 shows.” – bto: Das ist unser aller Vermögen und deshalb betrifft es uns alle, was wir daraus machen!

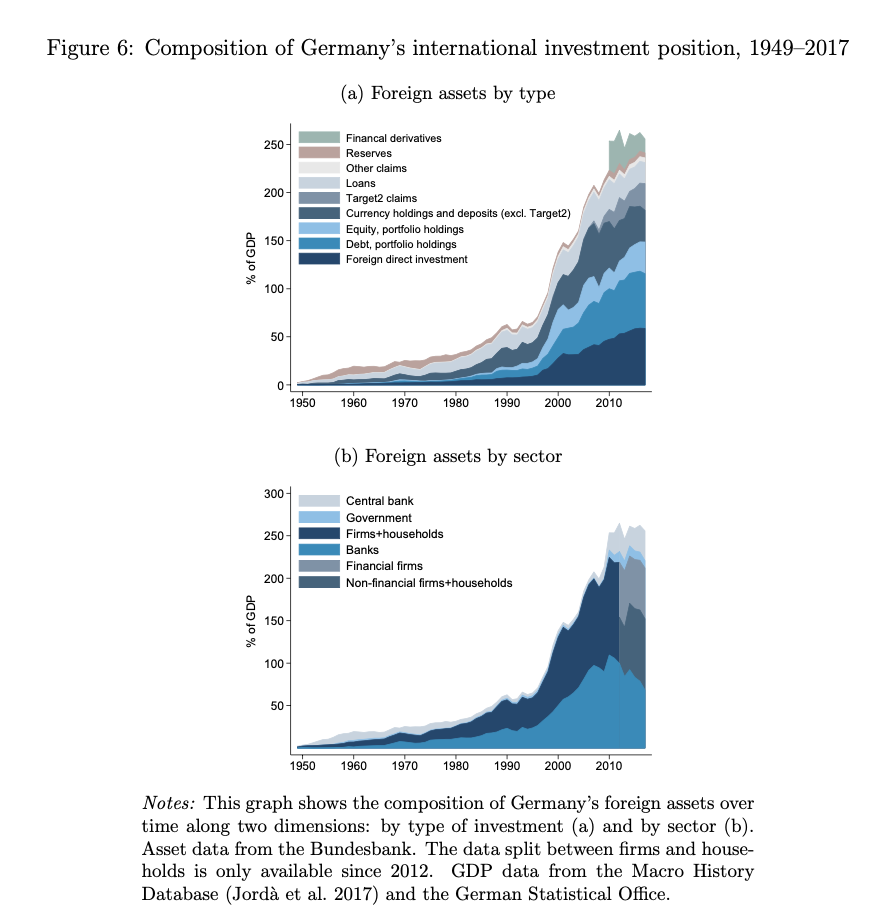

- “Furthermore, Figure 4 shows that Germany not only has a large net position but also a large gross position. Both the asset and liability positions rose strongly since the mid- 1990s and now amount to 256 % and 197 % of GDP respectively. While they initially grew in tandem leaving the net position at relatively small levels, the gap has been increasing since the mid-2000s and especially in recent years. While the net position has been positive over the entire post-war period with few exceptions, it currently stands at above 50 % of GDP. This reflects Germany’s sustained past current account surpluses.” – bto: Hier zeigt sich die ungesunde Hatz auf den Exportweltmeistertitel!

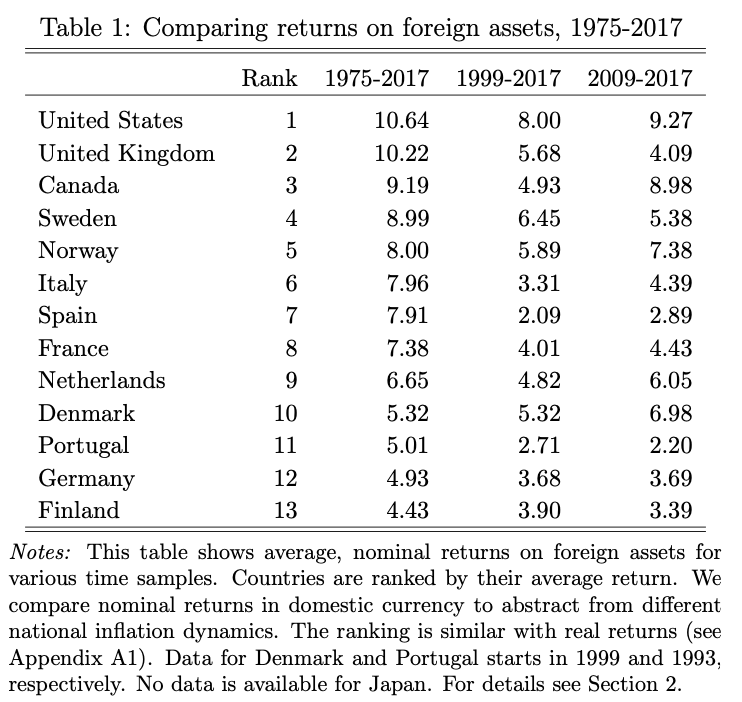

- “How does Germany’s international investment position (IIP) compare to accumulated capital exports? In a simple framework, one can think of Germany’s external asset portfolio as a savings account. Adding up all the payments that have flown into this account corre- spond to the historical book value of gross investments. The difference between historical costs and market value then reflects valuation gains on that portfolio. In other words, the larger the difference between the accumulated flow measure and the current market value of external investments, the higher the capital gains. Figure 5 demonstrates that the value of Germany’s (gross) foreign asset position very closely tracks the cumulated current accounts. This implies that the valuation gains, i.e., the wedge between historical flows and current market value, cannot have been large. In light of the multi-decade asset price boom that has characterized the world economy in the past decades this is clearly noteworthy.” – bto: “clearly noteworthy”, dass ich nicht heule. Es ist ein Ausweis außerordentlichen Versagens und es betrifft – ich wiederhole mich – uns alle!

- “Germany today is the world’s foremost exporter of savings. More than 300 billion Euros of German savings are sent abroad every year. Despite the heavy losses on American and other investments in the 2008 crisis, Germany has exported 2.7 trillion Euros in the past decade alone, equivalent to about 70% of GDP. These capital outflows came from German banks, firms, and households. Unlike in China or Japan, the public sector has played only a secondary role in the build-up of Germany’s foreign asset stock, despite the Bundesbank’s much-debated Target2 claims within the Eurosystem (2018, Target2 claims accounted for about 10% of Germany’s total external assets).” – bto: Das ist doch schon mal eine Aussage! 2.700 Milliarden wurden in das Ausland exportiert. Und was haben wir daraus gemacht?

- “Various voices in the domestic debate view Germany’s capital outflows favorably. Often-heard arguments include the potential for international risk sharing and as a hedge against adverse demographic trends, in line with the traditional textbook view. An aging country like Germany (…) can benefit from investing abroad and achieve better investment returns in younger, more dynamic economies abroad. Storing wealth abroad will also help for risk sharing and consumption insurance, for example when German households are hit by a recession while other countries are not, resulting in stabilizing capital income transfers from abroad.” – bto: Wie beim privaten Sparen setzt das aber voraus, dass man sich gut um seine Ersparnisse kümmert und das Geld intelligent anlegt!

Die Ergebnisse zusammengefasst:

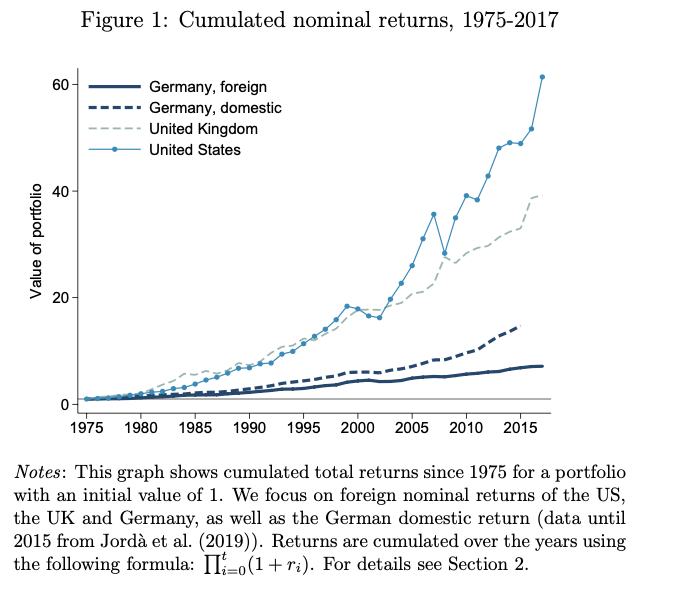

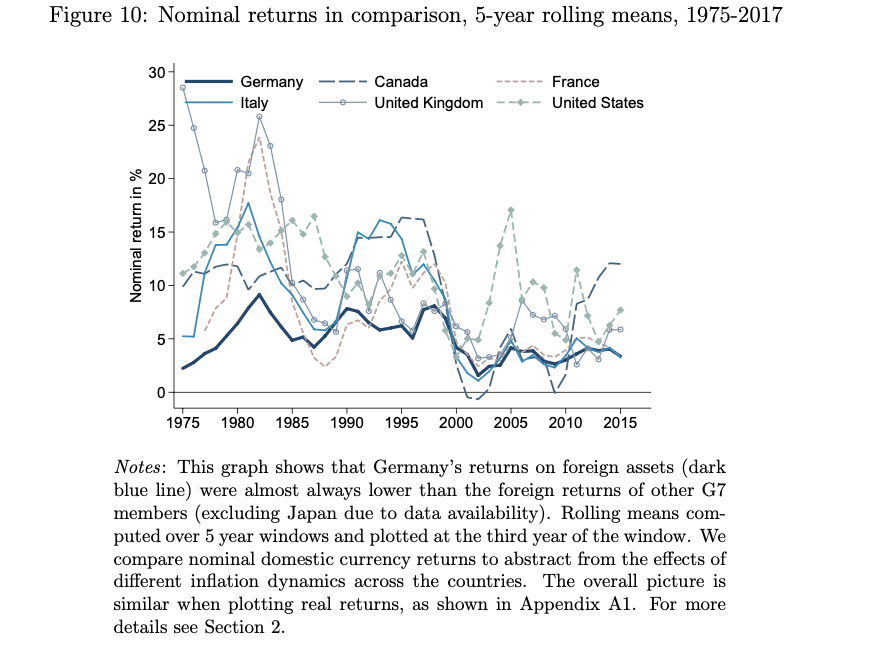

- “First, we find that the returns on German foreign assets are considerably lower than those earned by other countries investing abroad. Since 1975, the average of Germany’s yearly foreign returns was about 5 percentage points lower than that of the US and close to 3 percentage points lower than the average returns of other European countries. Germany fared particularly bad as an equity investor where investment returns under-performed by 4 percentage points annually.” – bto: Wenn ich 100 Euro anlege, werden daraus bei zehn Prozent pro Jahr von 1975 bis heute 7290 Euro, bei 5 Prozent pro Jahr 898 Euro – 6391 Euro Unterschied!

- “Second, we find that Germany earns significantly lower foreign returns within each asset category, after controlling for risk. This suggests that Germany’s weak financial performance abroad is not merely the result of a more conservative investment strategy that focuses on safer assets. The low German returns compared to other countries also cannot be explained by exchange rate effects (appreciation), nor by the recent build-up of Target2 balances. Instead, valuation losses are a big part of the explanation. The valuation of Germany’s external asset portfolio has stagnated or decreased, while other countries witnessed considerable capital gains, on average. Germany’s frequent investment losses are remarkable given that the world economy has witnessed a spectacular price boom across all major asset markets over the past 30 years.” – bto: In der Diskussion beim ifo Institut wird in diesem Zusammenhang erwähnt, dass es auch die Unternehmen sind, die falsche Investitionen tätigen und so im Ausland viel Geld verlieren. Man denke an ThyssenKrupp in Brasilien und an Bayer mit Monsanto.

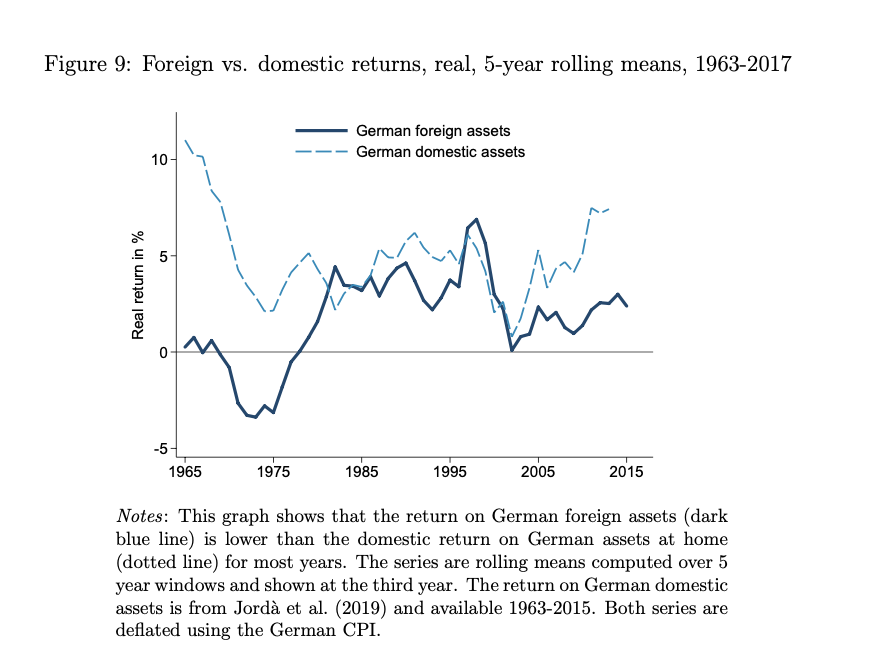

- “Third, German returns on foreign investment were considerably lower than the returns on domestic investment. This is an important insight for the policy debate on the merits of domestic vs. foreign investment. The difference was particularly pronounced in the last decade, when the average return on a domestic portfolio of German bonds, equity, and real estate was about 4 percentage points higher per year than the returns on Germany’s foreign assets.” – bto: Nun könnte man meinen, dass dies klar ist, weil man näher dran ist und es besser managed. Andererseits haben wir wie angesprochen einen weltweiten Boom der Vermögenswerte erlebt. Da muss man schon besonders doof sein, um so schlecht abzuschneiden.

- “Fourth, we find little evidence that foreign returns have positive effects for consumption insurance. The return on Germany’s external assets is highly correlated with German economic activity – even more so than domestic returns – and, thus, provides no hedge against domestic consumption shocks. Moreover, 70 % of Germany’s foreign assets are invested in other advanced economies that face similar demographic risks. In the past decade, less than 10 % of capital flows went to younger, more dynamic economies outside of Europe or North America, despite the fact that emerging markets now account for more than 50 % of world GDP.” – bto: Wobei die Assetmärkte gerade in den Industrieländern hochgegangen sind, die Schwellenländer underperformen schon eine Weile. Das heißt, die intellektuell eigentlich falsche regionale Allokation hätte in den letzten Jahren eine super Rendite erbringen müssen. Hat sie aber nicht.

- “Table 1 summarizes the main findings of the paper. The table ranks countries by their average return on foreign investments (…) Germany has the worst investment performance among the G7-countries. In the full country sample from 1975 to 2017, Germany ranks 12th, with only Finland performing worse. The picture looks similar if we consider the past decade (2009-2017), where Germany ranks on the 10th place. The same is true when we use real returns, deflating each country’s foreign asset returns with domestic inflation rates.“

- “The cumulative effects of these bad investment returns are quantitatively large, as can be illustrated with a simple counterfactual exercise. In the decade since the 2008 financial crisis alone, Germany could have become about 2 to 3 trillion Euros richer had its returns in global markets corresponded to those earned by Norway or Canada, respectively. This implies a (hypothetical) wealth loss of 70 to 95 % of German GDP (see Section 5 for details). On a per capita basis, this implies an amount of 28.000 to 37.300 Euros of foregone wealth for each German citizen (compared to the performance of Norway and Canada). These numbers are only an illustrative thought experiment, but they highlight the economic magnitude of high vs. low returns on foreign investments. (…) Figure 1 compares the total return performance of German foreign investments, US and UK external assets, as well as a portfolio of domestic German assets (stocks, bonds and houses). Assume you invested 1 Euro in global capital markets in 1975 and that you reinvest any dividends or interest gains. As of 2017, you would own 40 to 60 times of that initial investment had you followed the investment strategy of the UK or the US. In comparison, the initial investment only increased by a factor of 7 using the returns on German foreign assets (before inflation).”

Welche Rolle die Qualität der Geldanlage hat, ist übrigens auch daran ersichtlich, dass die USA seit Jahren ein Handelsdefizit fahren, sich also im Ausland verschulden und dennoch meist ein positives Auslandsvermögen haben. Nur wenn der Dollar stark aufwertet wie in den letzten Jahren, gibt es temporär ein negatives Auslandsvermögen. Bis zur nächsten – unweigerlich – kommenden Dollar-Abwertung. Insofern ist Donald Trump auf dem Holzweg mit seinem Blick auf das Handelsdefizit der USA.

Woran liegt es?

Da lohnt der Blick auf die Struktur des Auslandsvermögens und auf die Verwalter unseres Auslandsvermögens. Wiederum aus der bereits zitierten Studie:

- “The rise in the overall level in assets was largely driven by increases in foreign direct investment and portfolio investment reflecting increasing international financial integration. Reserve assets on the other hand made up 20 – 30 % of all assets until the 1970s and have become almost irrelevant today. Target2 balances have been increasing in recent years but only represent about 10 % of all assets. As Target2 balances do not generate income, they could potentially bias our estimated downwards, and throughout the paper we will pay close attention that our findings are unaffected by this.” – bto: Es liegt also nicht daran, dass wir auf die TARGET2-Forderungen keine Zinsen bekommen. Schon so sind unsere Erträge schwach.

- “In addition to the composition by functional category, one can also decompose the foreign asset position by domestic sectors. Here, the balance of payments distinguishes between four broad sectors: banks, firms and households, the government, and the central bank. In more recent data, the non-bank private sector is further split into financial firms and non-financial firms plus households. The panel shows that the increase in gross position since the 1990s was mainly driven by banks increasing their exposure relative to GDP. However, since the financial crisis the banking sector reduced its exposure. This decline has been partially offset by non-financial firms.” – bto: Dass unsere Banken nicht gerade Weltklasse sind, wissen wir schon lange. Es genügt auch ein Blick auf die Ranglisten der größten Banken der Welt, um zu erkennen, dass das Finanzwesen nicht gerade eine Stärke der Deutschen ist. Dies ist als solches nicht schlimm, nur muss man sich dann Profis holen.

Und das Ergebnis ist ernüchternd.

Zum einen würden wir mehr verdienen, wenn wir unsere Ersparnisse im Inland anlegten:

Zum anderen sind wir im internationalen Vergleich einfach nur schlecht:

Was zur Frage führt: Woran liegt es? Darüber kann man nur spekulieren. Die Forscher haben es bewusst um die Folgen von Währungsaufwertungen korrigiert. Es liegt also wirklich an der Art der Geldanlage. Wir können oder wollen es offensichtlich nicht richtig machen. Deshalb sollten wir zwei Dinge tun:

- weniger im Ausland anlegen,

- unsere Anlagen im Ausland besser managen.

Soweit ich sehe, ist Joerg der einzige, der tatsächlich versucht, einige Hypothesen zu entwickeln, warum die deutschen Auslandsforderungen so geringe Erträge erwirtschaften.

An dem risikoaversen Anlageverhalten der Deutschen kann es nicht liegen, denn der Graphik zufolge wird das Auslandsvermögen zum grössten Teil von Banken, anderen Finanzunternehmen und Nichtfinanz-Firmen gehalten.

Aber der Artikel scheint einen guten Anlass zu liefern, auf den Youtube – Kanälen junger Influencerinnen gründlich zu recherchieren.

@Rolf Peter

“Aber der Artikel scheint einen guten Anlass zu liefern, auf den Youtube – Kanälen junger Influencerinnen gründlich zu recherchieren.”

Soll ich meine dazu gehörige Hypothese ein bisschen weniger pointiert formulieren, damit sie auch von Ihnen begriffen werden kann? ;)

@Joerg

“Ein großer Teil der renditeschwachen Anlage erklärt sich mit Wertverlusten: In den meisten Jahren seit den 1970ern stagnierte oder sank der Wert des deutschen Anlageportfolios, während die Portfolios anderer Länder tendenziell Wertsteigerungen hatten. Wechselkurseffekte können dieses Resultat nicht erklären.”

https://www.ifw-kiel.de/de/publikationen/medieninformationen/2019/deutschland-verdient-weniger-mit-auslandsanlagen-als-andere-laender/

Man denke z.B. nur an die deutschen Landesbanken… oder Thyssen in Brasilien, Bayer kauft Monsanto , Deutsche Bank kaufte Bankers Trust )(lange ist es her) für fast 10 Mrd $ und war beim Corona Tief 2020 als gesamte Bank nur noch rd 10 Mrd € wert…

Ändert aber nichts daran, dass D Privatanleger langfristig auch besser investieren sollten

Heute kann man ja nachlesen, auch in der Schweizer Presse, wie “erfolgreich” Deutschland sein Geld “anlegt”…Ups

https://www.20min.ch/story/die-zahlungen-an-budapest-und-warschau-muessen-gestoppt-werden-261705481799

Nebenbei:

Man beachte, am Ende des Artikels, die kleine Umfrage …..”Wärst du für einen EU-Beitritt der Schweiz?”

In der Branche gab es dafür früher einen treffenden Ausdruck: “stupid German money”.

Ich denke, es liegt erstens an der fehlenden finanziellen Bildung in buchstäblich allen Bevölkerungsschichten, auch den vermeintlich gebildeten oder sich selbst dafür haltenden. Vom sich selbst überschätzenden Juristen, der glaubt, dass etwas eingehalten wird, nur weil es in seinem Vertrag steht, über die sprichwörtlichen renditesuchenden Zahnärzte am grauen Kapitalmarkt bis zu den Studienfächern mit Ökonomie, bei denen vor allem die Theorien und statistische Modelle im Vordergrund stehen. Sie können problemlos BWL studieren, ohne mit den Problemen einer “asset allocation”, der österreichischen Schule der Nationalökonomie oder den praktischen Problemen des Aktienmarktes wie z.B. einer geringen Marktkapitalisierung konfrontiert zu werden, wissen aber im Gegenzug viel über Regressionsanalysen, strategisches Controlling und zwölf Definitionen des Wortes “Marketing”. Bringt Ihnen nur bei der Geldanlage hinterher nicht viel.

Am schlimmsten sind aber zweitens in Deutschland die gesellschaftlichen Extreme. Der eine Teil der Bevölkerung ist sicherheitsbesessen (z.B. reine Sparbuchinhaber, Kapital-LV-Besitzer mit Mindestverzinsung, Riester-Sparer, etc.) und bekommt deswegen keine Rendite; der andere ist zu gierig und fällt auf Schneeballsysteme, Phantasierenditen und vermeintliche Steuersparvorteile herein.

Es fehlt also an einer entsprechenden Kultur. Sie können auf einer beliebigen gesellschaftlichen Veranstaltung (z.B. Geburtstagsparty, Firmenjubiläum, Einweihungsfeier, etc.) über Ihre Krankheiten, asiatische Religionen, die Vor- und Nachteile der aktuellen Kanzlerkandidaten oder die Schulnoten Ihrer Kinder sprechen. Der Geräuschpegel wird sich nicht ändern. Aber wehe, Sie stellen Fragen nach dem Motto: “Und wie legst Du gerade Dein Geld an?” oder “Wie hoch ist Deine ETF-Quote?” Da geht der Geräuschpegel im Raum aber zeitnah runter…^^

Die Deutschen werden dann erfolgreicher, wenn bei Friseuren auch mal Zeitschriften ausliegen, die sich statt mit Mitgliedern europäischer Königshäuser mit Aktiendepots beschäftigen. Und wenn die Frage “Was machst Du so beruflich?” ohne besondere Vorkommnisse von der Frage “Und wie legst Du Dein Geld an?” begleitet werden kann. Vorher meines Erachtens nicht.

“Doppeldaumen hoch”

@Wolfgang Selig

“Es fehlt also an einer entsprechenden Kultur.”

Zustimmung !

“Kultur” ist aber eng mit Bildung, Eigenverantwortung usw. verknüpft und um Diese steht es ja bekanntlich immer schlechter.

Wer diese fehlende Anlage”kultur” schon bei der älter Generation feststellt nzw. vermisst, der kann sich ja ausmalen, wie es “kulturell” bei den jungen Generation steht.

Herr Kraus, der ehemalige Vorsitzende des deutschen Lehrerverbands (DL),prangert diesen Bildungsverlust (nebst Heinsohn usw.) seit Jahren in seinen Büchern und Vorträgen an.

Wie man eine ehemalige Bildungsnation an die Wand fährt bzw. gefahren hat, beschreibt er eindrücklich aus seinem Arbeitsleben :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHA6VtA5fsw

Exakt, volle Zustimmung!

Eigenverantwortung ist auch als neoliberal/kapitalistisch verpönt.

Dazu ein großartiges Video von einer jungen lifestyle-linken deutschen Influencerin (übrigens mit Engagement beim Staatsfunk…), die ein bisschen die pseudointellektuelle Nische bedient und regelmäßig Videos mit Buchempfehlungen dreht. Und einmal war doch tatsächlich auch ein Buch über Finanzen auf der Liste und wurde von ihr besprochen:

https://youtu.be/7n5OpEHTBlg?t=626

@Richard Ott

Die Influencerin ist nicht mal auf dem neuesten Stand- nach meinen Beobachtungen wird viel Energie in Versuche inverstiert, als ” Model” entdeckt zu werden, beliebtes Berufsziel auch bei Abiturientinnen. Noch besser: Flirtschulen, wie-angele-ich-mir-einen-Millionär, bring´die Brunstkettte in Schwung:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQho0huOjNU

List-Strategieen zu kennen sind immer hilfreich, s. Harro v. Sengers Werke.

Naja, in der Moskauer “Luderschule” war Boris Reitschuster schon 2006, so neu ist das nicht, und im linksgrünen Berlin würden junge Influencerinnen sicher auch keinen Millionär mehr wollen, wenn er nicht wenigstens genderqueer oder noch beser transsexuell ist – schon wegen des Sozialprestiges…

https://reitschuster.de/post/einsatz-an-der-erotik-front/

Für ihre Generation hier in Deutschland ist die Influencerin allerdings typsich. Sie hat es irgendwie geschafft, einen Podcast über Politikthemen im öffentlich-rechtlichen Jugendradio zu moderieren, obwohl sie von Wirtschaftsthemen absolut keine Ahnung hat und auch noch stolz darauf ist. Allerdings findet sie es trotzdem ganz wichtig, dass es mehr Frauen in der Finanzbranche gibt, weil das so eine männer-dominierte Welt ist (und sie vermutlich irgendwo gehört hat, dass man da viel Geld verdienen kann). Da fällt mir auch nichts mehr ein.

Wenn sie nur ein bisschen faul wäre und nicht komplett arbeitsunwillig, dann hätte sie das Buch ja zumindest soweit lesen und verstehen können, dass sie sich einen MSCI World ETF Sparplan aufmacht und sich dann nie wieder um das Thema kümmert, aber selbst das ist wohl schon zu viel verlangt.

Tja, stupid German money, immerhin wird sie von meinen Zwangsgebühren mit versorgt.

“Target2 balances do not generate income, they could potentially bias our estimated downwards, and throughout the paper we will pay close attention that our findings are unaffected by this.”

Die Studie stellt aber auch fest, dass die Target 2 – Salden die jährlichen Nominalerträge des Deutschen Auslandsvermögens um 0,23 Prozentpunkte senken, da sie nicht verzinst werden. Gleichzeitig werden die Sparguthaben im Inland mit minus 0,5 % p.a. belastet. Somit handelt die EZB zu Lasten Deutschlands (Negativzinsen) und die Konstruktion des Target 2 geht ebenfalls zu Lasten Deutschlands (Null Ertrag).

70 % aller “foreign assets” sind in Europa belegen, also in einer relativ statischen Umgebung mit geringen Wachstumsaussichten. Dies ist unter zwei Aspekten negativ, zum einen wegen der Festschreibung niedriger Erträge auch in Zukunft, zum anderen wegen des Erpressungspotentials über die EU-Gremien, da von Deutschland immer weitere Finanzleistungen verlangt werden können mit der Drohung: Verlust der Kredite / Darlehen / Anleihen.

Die Asset Allocation zwischen Debt und Equity ist ebenfalls falsch gewichtet zu Lasten zukünftiger Gewinnchancen.

Verständlich wäre das bei ausländischen Firmenvermögen nur dann, wenn Darlehen zur Finanzierung des Auslandsvermögens innerhalb von Konzernen dienen. Dann können Gewinne über Zinslasten und Verrechnungspreise gesteuert werden, es muss also nicht zwingend Eigenkapital im Ausland arbeiten.

Aber in der Schlussfolgerung richtig: Es fehlt an echt international qualifizierten Fachpersonal in vielen deutschen Banken. Daher geht auch Listenplatz 1 und 2 an die USA und UK. Wie ich finde zu Recht, da die besten Investmentbanken in NY und London beheimatet sind.

@Gnomae

“Gleichzeitig werden die Sparguthaben im Inland mit minus 0,5 % p.a. belastet. Somit handelt die EZB zu Lasten Deutschlands (Negativzinsen) und die Konstruktion des Target 2 geht ebenfalls zu Lasten Deutschlands (Null Ertrag).”

Niemand hindert die Privathaushalte in D daran, statt un- oder negativ verzinste Kontoguthaben mehr in Sachwerte (gerade außerhalb D) zu investieren. Dafür braucht man noch nicht einmal überbezahlte Investmentbanker. Die Einstellung der D zu Geldanlagen, die geht zu Lasten Deutschlands, ja. Daran sind “wir” aber selbst schuld,

@ troodon, 16:17

Zum Umfang der Negativzinsen: Die Kosten negativer Einlagenzinsen der EZB für Banken in Deutschland von 2015 bis einschließlich 2021 belaufen sich auf 13,21 Mrd. DM, allein in 2021 ein Betrag von EUR 4,49 Mrd. EUR.

Den Banken in Deutschland sind also 13,21 Mrd. durch die EZB entzogen worden, damit dem deutschen Sparer, ohne Rechtsgrundlage.

@ Gnomae

Was MÜSSTE die angeblich fehlende Rechtsgrundlage denn sein, damit die EZB die Banken mit Negativzinsen belasten kann?

Was hat das URSÄCHLICH mit dem „deutschen Sparer“ zu tun?

@Gnomae

Abgesehen von der Frage von Hr.Tischer, betrachten Sie die (Negativzins-) Medaille bitte von beiden Seiten.

Finanz-Szene.de hat da etliche Artikel dazu.

Durch das Tiering und die TLTRO mit bis zu -1% ist es seit 2020 nicht mehr so, dass man pauschal behaupten sollte, dass die (deutschen) Banken durch Negativzinsen netto erhebliche Belastungen haben.

Nachstehend ein Link, von dem man sich dann etliche Artikel durchlesen kann. Alternativ hilft auch die Suchfunktion auf der Finanz Szene HP

https://finanz-szene.de/banking/ezb-negativzinsen-werden-zum-milliarden-plusgeschaeft-fuer-banken/

@Gnomae

Das qualifizierte Fachpersonal findet sich in DE bei Versicherungen und Pensionskassen.

Diese sind staatlich reguliert und verwalten Anlageklassen, die öffentliche Förderung und Promotion genießen.

Wenn man die Vergangenheit kritisch betrachtet, muss man wohl zu dem Schluss kommen, dass Vermögensbildung für breite Bevölkerungsschichten nie ein vorrangiges Ziel war, sondern dass oft die staatliche Mittelakquirierung im Vordergrund stand ( Stichwort: Aufbau Ost )

Und so darf man sich nicht wundern über die hierzulande fast neurotische Sicherheitskultur und die mangelnde Kompetenz in Geldanlagen.

Hier ist man allenfalls noch in Immobilien, denn “die steigen ja immer”.

@ jobi

Alles richtig.

Und:

Man kann die „fast neurotische Sicherheitskultur“ der Vergangenheit getrost fortschreiben.

Das wirklich Fatale daran:

Wer bemüht INDIVIDUELL für sich sorgt, kann nicht anders, als die Ursache bei sich selbst suchen, wenn die Erwartungen enttäuscht werden.

Wer gutgläubig ANDERE für sich sorgen lässt, wird in diesem Fall was tun?

SCHULDIGE suchen – im Zweifelsfall der Regierung Versagen vorwerfen.

Auch so kann eine Gesellschaft degenerieren.

“Wer gutgläubig ANDERE für sich sorgen lässt, wird in diesem Fall was tun? SCHULDIGE suchen – im Zweifelsfall der Regierung Versagen vorwerfen.”

Mein Mitleid mit den enttäuschten Sicherheitsneurotikern wird sich in Grenzen halten.

Hoffentlich verliert der Staat in so einem Szenario so viel an Unterstützung, dass er in seiner Größe deutlich zurechtgestutzt wird und viel weniger Minderleister mit Parteibuch in ihm ein üppig finanziertes Auskommen finden können als es jetzt noch der Fall ist.

@ Richard Ott

>… verliert der Staat in so einem Szenario so viel an Unterstützung, dass er in seiner Größe deutlich zurechtgestutzt wird…>

Das wäre ja was – positiv, man könnte sich über die „Korrektur“ freuen.

Was aber, wenn so viel VERTRAUEN verloren wird, dass er NICHT mehr funktioniert?

Das ist nicht auszuschließen.

Nur weil das bisher nicht der Fall ist, muss es nicht heißen, dass es NIE der Fall sein wird.

Man muss zwar nicht immer mit dem Schlimmsten rechnen, sollte aber schon sehen, ob das Schlimmste mehr ins Blickfeld rückt, wenn man auf einem bestimmten gesellschaftlichen Pfad ist.

@Herr Tischer

“Was aber, wenn so viel VERTRAUEN verloren wird, dass er NICHT mehr funktioniert?”

Dann werden wir wohl eher italienische Verhältnisse bekommen als komplette Anarchie.

Mit einem Operettenstaat, theatralischen aber inhaltlich entkernten Institutionen und einem Volk, das grinsend oder auch kopfschüttelnd das Schauspiel betrachtet und ansonsten ganz viel schwarz arbeitet und Steuern hinterzieht.

@Herr Stelter

nun gab’s keinen Link zu den Orginalquellen, aber ich bin ungluecklich mit der pauschalen Subsummierung ohne die Einfluss-/Anteilaufschluesselung der einzelnen Effekte nachpruefen zu koennen.

a) die Groessenordnungen: in Fig.6a wird schon mal deutlich, dass “viel Geld” erst relativ kurzfristig (25 Jahre Globalisierung?) im Spiel ist. Die “Comparing returns” aber in Tab.1 fuer drei Zeitabschnitte (warum gerade diese Einteilung?) dargestellt werden. Gab es vielleicht Situationen (zeitlich und mengenmaessig) besonders schlechter Auslandsanlagen?

b) Dtsch Besonderheiten in den letzten 25 Jahren? Da fallen mir ein:

– Internet-Bubble: 1998-2000 investierten viele dtsch/unerf. Privatanleger (wie mich ;-)) und Firmen in den USA und befeuerten die Internetbubble mit?!

– Immobilien-Krise: 2003-2007 investierten viele dtsch Privatanleger (ohne mich), Versicherungen, Landesbanken, Geschaeftsbanken in US CDOs, CLOs, Zertifikate, etc

– Grossmanns-Sucht?: einiger unserer “besten” Wirtschaftskapitaene (Telekom(Sommer?), Thyssen-Krupp(Brasilien-Desaster), Daimler(Chrysler-Schrempp?), D.Bank, Bayer(Monsanto), etc) fuehrten zu Milliardengrab-Investition oder -Uebernahmen im Ausland

– Target2-Claims: relativ gesehen (im Vgl mit anderen EU-Staaten), ist der potentielle? Rendite-Schaden fuer uns stets groesser als fuer die europ. Nachbarn? Ist das nicht systeminnewohnend?

– MisterX hat schon auf die Unterschiede der Industrien hingewiesen

Im Nachhinein ist man immer schlauer:

Die Boersenerfahrung/wirtschaftliche BILDUNG ist bei uns in der Breite sicher immer noch unterentwickelt (aber das wird langsam?).

Sind wir als Gesamtheit eher Gier- oder Angst-anfaellig bzw UNERFAHRENER mit RISIKEN oder gar RISIKOAVERS als dtsch Charaktereigenschaft?

(Gier nach Internetbubble-Gewinnen einerseits, dann Angst vor Aktienwert-Schwankungen andererseits; Gier nach hohen Zinsen von CDOs/CLOs/Zertifikaten etc einerseits, Angst vor Unplanbarkeit und Unsicherheit beim Unternehmertum?)

Gibt’s auch einen Mental-Accounting Effekt wegen unseres Hochsteuer-Biotops? So quasi: schlechte Auslandsanlagen sind nicht so schlimm (nicht genauso intensiv hinschauen wie hierzulande), weil ich es von den hiesigen Steuerforderungen abschreiben kann (umgekehrt: zu hohe Auslandsgewinne, kann man hier gar nicht gut verstecken/repatriieren)? Oder Bloedsinn/marginal?

LG Joerg

Doch. Der Link befindet sich im Text bevor es losgeht.

Man kann es auch kürzer zusammenfassen. Die englische Sprache hat dafür den passenden Ausruck:

The German is the underdog.

>Woran liegt es? Darüber kann man nur spekulieren.>

Letztlich ja, aber man kann auch plausibel spekulieren.

>Es liegt also wirklich an der Art der Geldanlage.>

Daran liegt es nicht – sie ZEIGT nur das schlechte Ergebnis.

>Wir können oder wollen es offensichtlich nicht richtig machen.>

So ist es – empirisch festgestellt.

Plausibel spekuliert, WARUM das so ist:

Wir Deutschen sind in großer Zahl davon überzeugt, besser: mentalitätsmäßig darauf FIXIERT, dass es genügt, Weltmeister im Export zu sein, also anerkannter- und bewiesenermaßen als Top zu gelten, dadurch vergleichsweise hohe Einkommen zu erzielen und mit Steuern und Abgaben vom Staat den Anspruch erfüllt zu bekommen, bis zum Lebensende ein weitgehend gut gesichertes Auskommen haben zu können.

Was darüber hinaus gespart werden kann, fließt aufs Bankkonto oder in die Kapitallebensversicherung.

Wer will bei so VIEL Sicherheit noch RISIKEN eingehen und EIGNER von produktiven Sachwerten werden, deren Wertentwicklung – vor allem im Ausland als undurchsichtig erachtet – man nicht versteht?

Viel zu wenige.

Demografische und technologische Entwicklungen, die Verschiebung der Gewichte in Welt werden nicht mitgedacht.

Man realisiert nicht den fundamentalen Wandel – die Exportüberschüsse SIGNALISIEREN doch, dass kein uns belastender stattfindet.

Das Ausblenden wird weiterhin und vermutlich sogar verstärkt so sein, wenn mit verschärfter Klimapolitik die Unsicherheit wächst.

Abgesehen davon bin ich IRRITIERT.

Wenn die Aussage

>Wir können oder wollen es offensichtlich nicht richtig machen.>

RICHTIG ist, dann verstehe ich die Schlussfolgerung daraus nicht:

>Deshalb sollten wir zwei Dinge tun:

• weniger im Ausland anlegen,

• unsere Anlagen im Ausland besser managen.>

Wenn wir es NICHT richtig machen können und wollen, können wir diese zwei Dinge – richtige – eben auch NICHT wollen und tun.

WÜNSCHEN können wir uns das, aber das ist es dann auch schon.

Wenn der Zug auf den Gleisen fährt, werden sie nicht umgebaut.

Kann es daran liegen, dass teilweise unsere Exportindustrien, wie Automobilbau und sicher so etwas wie ThyssenKrupp (wenn man von den Fahrstühlen absieht), wie überall auf der Welt einfach immer schon wenig ertragreich waren, weil extrem kapitalintensiv ? Niedriges ROCE bzw ROIC. Weiss jeder der Aktieninvestments betreibt. In die Autobranche will man langfristig nicht investieren. Miese unregelmäßige Erträge relativ zu den Kapitalkosten. In den DAX will man nicht investieren. Die schaffen vielleicht viele Arbeitsplätze aber vergleichsweise wenig Rendite auf das eingesetzte Kapital. Ebenso der Maschinenbau in vielen Fällen. Könnte es sein, dass die Hidden Champions die vielleicht in ertragreicheren Nischen unterwegs sind, einfach mehr im Inland anlegen? Die Amerikaner haben viele sehr profitable Unternehmen insbesondere in viel profitableren Branchen, Konsumgüter, Software etc. nicht nur miese Branchen wie Autobauer, die dann eben auch in Auslandsinvestitionen mehr verdienen, weil sie immer mehr auf ihr eingesetztes Kapital verdienen. Aber vielleicht kommt ROCE in volkswirtschaftlichen Theorien nicht vor, und man glaubt da ernsthaft es macht keinen Unterschied ob man Autobauer ist und eher so 4 bis 10% auf das eingesetzte Kapital oder 15 bis 30% wie in guten Branchen. Die Apples, Softwareunternehmen etc

@ mister x

……… oder vielleicht auch, weil die gewinne durch geschickte steuer-konstruktionen versteckt und nicht mehr zurückfließen, – die belastungen aber schon?

zb. die konstruktionen über niederlande und luxenburg

……. von allen politiker gedeckt!

……… wenn dies die fließenden, kumulierten zahlen sind, welche ex- und in-fließen, dann

vermute ich mal, dass diese beinhalten,

was zb

-gastarbeiter

-wirtschaftsflüchtlinge und schlepperkosten

-transferleistungen durch versicherungsfremde leistungen aus den sozialkassen

-zahlungen und leistungen an israel

-kriegsfolge lasten und -schulden-vielleicht auch durch überhöte gebühren

-zusätzlich staatliche hilfen-rettungen zb in der EU

ans ausland fließen

ohne dies bei dem anlagekapital zu diferenzieren

…………. eine deutsche “erbschuld” ?

aus der interessenslage, könnte man dies durchaus vermuten!

*Wollen* wir denn überhaupt mit unseren Auslandsanlagen Gewinn machen?

Oder ist es nicht viel wichtiger, die Welt zu retten?

Oder das großartige Wohlstands- und Friedensprojekt EU, von dem wir Deutschen angeblich so sehr profitieren, um jeden Preis zusammenzuhalten?

@ Richard Ott

Man stelle sich vor, D würde die höchste Rendite aller Länder auf sein Auslandsvermögen erzielen. → Das wäre doch wirklich ungerecht den anderen gegenüber ;) In weiten Teilen unvermögend :) , aber trotzdem generös als Land sein, dass muss man erst einmal schaffen…

@troodon

“Man stelle sich vor, D würde die höchste Rendite aller Länder auf sein Auslandsvermögen erzielen.”

Kolonialismus! Das Buzzword, das dann hier in Deutschland käme, wäre “Kolonialismus”, denn um eine hohe Rendite auf Auslandsinvestitionen zu erzielen müsste man das Zielland selbstverständlich ausbeuten. (Wenn wir hingegen nicht im Ausland investieren, dann enthalten wir den anderen Ländern natürlich die “Teilhabe” an unserer Technologie vor und betreiben schlimmstenfalls Protektionismus, das ist auch schlecht und gibt Gemecker von links…)

Es gibt auch schon laut Selbstbezeichnung “anti-kolonialistische” Klimahüpfkids hier in Deutschland, ich hab nur keine Ahnung, was die mir mit ihren politischen Äußerungen eigentlich sagen wollen.

https://twitter.com/antikoloniale/status/1421478401580408832

(Achten Sie auch auf das großartige T-shirt bei der migrantischen Freiheitskämpfer*in rechts im Bild…)

Aber vermutlich werden da einfach wortgetreu Reden von der Antifa Portland ins Deutsche übersetzt.

@ ott

…… es gibt halt gute und böse ausbeuter! national und global!

entscheidend ist, wer es macht!