“How Low Will The S&P Go? Buffett & Shiller Know…”

Im Einkauf liegt der Gewinn. Daran habe ich immer wieder bei bto erinnert, zuletzt bei meinem Blick auf die Börse in London. Dabei eignen sich die Bewertungen nicht, um Einbrüche an den Börsen vorherzusagen, sie eignen sich aber, um künftige Erträge zu prognostizieren.

Wie es für die USA zurzeit aussieht, fasst ein Analyst hier zusammen, zitiert via Zero Hedge, da das Original nicht verfügbar:

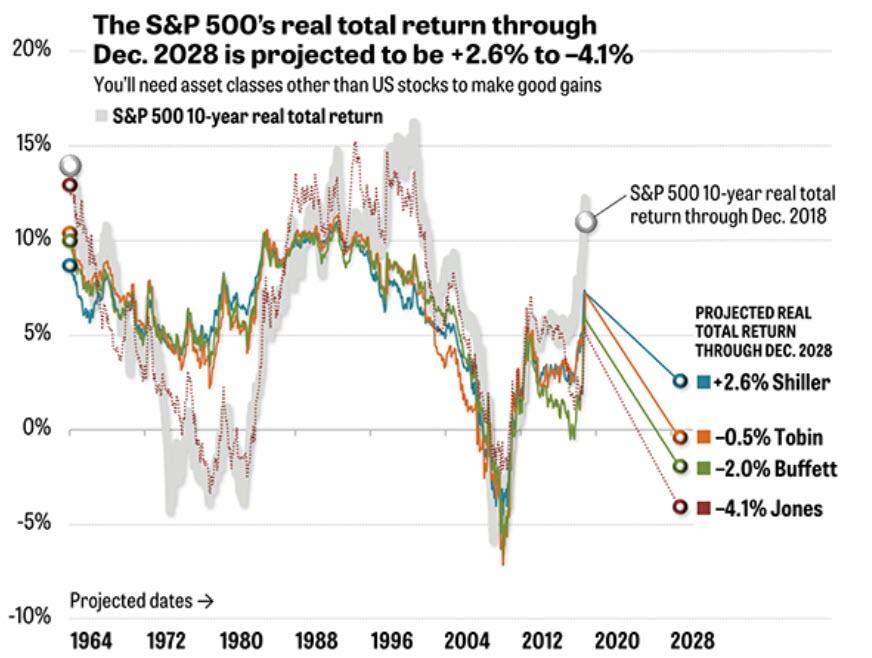

- “Financial experts like Warren Buffett and Robert Shiller are creators of long-term projection methods with data that goes back more than half a century. It’s well known that Buffett is one of the world’s richest people, and that Shiller won a 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics partly for developing his forecasting formula. Whether or not these seers actually have crystal balls, things have worked out pretty well for them.” – bto: Und deshalb werden vier Methoden auf die US-Börse angewandt.

“The graph above doesn’t show the S&P 500’s price levels. Instead, it reveals how well the projection methods estimated the market’s 10-year rate of return in the past. The round markers on the right are the forecasts for the 10 years that lie ahead of us. All of the numbers for the S&P 500 include dividends but exclude the consumer-price index’s inflationary effect on stock prices.” – bto: Es sind also reale Erträge inklusive Dividenden.

- “Shiller’s P/E10 predicts a 2.6% annualized real total return. Take today’s S&P 500 price and divide it by its companies’ average inflation-adjusted earnings over the past 10 years. This gives you a ratio that suggests whether the market is overpriced or underpriced. If you could buy one ‘share’ of the S&P 500 index, your account would be worth around $2,700. After 10 years of 2.6% gains, you’d have $3,490.” – bto: Die Annahme dahinter ist, dass das Shiller-KGV zum langfristigen Durchschnitt konvergiert. Das ist nicht implausibel.

- “Buffett’s MV/GDP says minus 2.0%. Divide the S&P 500’s market value by the U.S. gross domestic product. Buffett wasn’t the first person to suggest this metric, but he’s said on the record that it’s ‘probably the best single measure of where valuations stand.’ If the index fell 2.0% annualized, your $2,700 would turn into $2,206. Not so great.” – bto: Die Börse ist also relativ zum BIP teuer. Fällt die Quote auf den langfristigen Durchschnitt, ergibt sich sogar ein absoluter Verlust.

- “Tobin’s ‘q’ ratio indicates minus 0.5%. This metric divides the market value of all U.S. equities (not just the ones in the S&P 500) by the cost to replace all of the companies’ assets. It’s based on academic papers by economists James Tobin, a 1981 Nobel laureate, and William Brainard. This formula predicts that your S&P 500 account will drift slightly lower in real terms, not quite keeping up with inflation.” – bto: wobei ich hier noch skeptischer wäre. Die Bilanzen der Unternehmen waren früher seriöser. Heute wird zu viel gefudged.

- “Jones’s Composite says minus 4.1%. Jones uses Buffett’s formula but adjusts for demographic changes. For example, as America’s population ages, this reduces economic demand. The resulting Demographically and Market-Adjusted (DAMA) Composite has predicted the S&P 500’s 10-year returns more closely than any of the other formulas since 1964. Let’s hope he’s wrong. A 4.1% annualized loss would drive your $2,700 account down to $1,776 after 10 years. That would be a 34% decline, almost as bad as the ‘lost decade’ of 2000 through 2009.” – bto: Auch das klingt undenkbar, was aber nicht bedeutet, dass es unrealistisch ist.

“(…) these formulas (…) aren’t guarantees and can’t be used to time the market. (…) ‘The market’s return over the past 10 years,’ Jones explains, ‘has outperformed all major forecasts from 10 years prior by more than any other 10-year period.’ He attributes this to the unprecedented stimulation that the Federal Reserve pumped into the economy (and is now removing — watch out below). Markets tend to revert to their average performance over time, which is not nearly as much fun as it sounds.” – bto: Das leuchtet zu 100 Prozent ein. Es kann keine dauerhafte Abweichung von fundamental gerechtfertigten Werten geben, selbst, wenn die Notenbanken es noch so sehr versuchen. Klar, sie können das Geld völlig entwerten. Besser Sach- als Finanzwert. Dennoch bleibt real nur ein besserer Vermögenserhalt. Relativ.

Das spricht für Diversifikation: “Those diversifying assets include real-estate investment trusts, commodities, precious metals, and non-US stocks and bonds.” – bto: Das gilt aus US-Sicht. Deutsche Assets sollten das aber nicht unbedingt sein, sind wir doch die großen Verlierer des Euro-Endgames.

→ zerohedge.com: “How Low Will The S&P Go? Buffett & Shiller Know…”, 29. Januar 2019

@ Michael Stöcker, Wolfgang Selig et. al.

Zur „Gerechtigkeits-Diskussion“:

Eine Gretchenfrage gegen die andere – das ist unergiebig, weil es zu keiner Klärung führt.

Es geht anders und besser so:

Man muss eine GRUNDPOSITION einnehmen und von dieser als Prämisse bzw. Zielvorstellung argumentieren.

Die Methodik dahinter:

Wenn ich das Ziel X will, weil ich es als am vernünftigsten, vorteilhaftesten etc. ansehe, MUSS ich auch die MITTEL dafür wollen. Sie nicht zu wollen, wäre inkonsistent.

Es ist auch inkonsistent, möglichst viel von allem zu wollen (die irregeleitete Grundbefindlichkeit unserer Gesellschaft).

Meine Grundposition und davon abgeleitet als Ziel formuliert (was ein begründetes, aber kein absolut letztbegründbares sein kann, wie jedes andere auch):

Die GEGENWÄRTIGE Gesellschaft wird durch ein hohes materielles Wohlstandsniveau zusammengehalten. Fällt es erheblich, nehmen die Konflikte in der Gesellschaft zu bis möglicherweise dem Punkt, an dem sie nicht mehr funktionsfähig ist.

Um umfassende Disfunktion oder gar Zerfall der Gesellschaft zu vermeiden, muss das Wohlstandsniveau gehalten werden. Es ist ein modifizierbares Wohlstandsniveau, das z. B. auch eine andere Verkehrssituation in den Städten erlauben kann (ist hier nicht das Thema).

Es wird in einer sich global schnell und umfassend verändernden Welt durch Marktwirtschaft erhalten, weil sie über die effizientesten und effektivsten Anpassungsmechanismen verfügt.

Marktwirtschaft schafft Ungleichheit (insbesondere hinsichtlich Vermögen und Einkommen) aufgrund des ihr inhärenten Belohnungsmechanismus.

Wer Marktwirtschaft WILL, akzeptiert Ungleichheit, ohne aufgrund der Tatsache, dass es sie gibt, sich irgendwelche Vorwürfe zu machen oder sich schon dadurch mit einem schlechten Gewissen zu Kompensationsmaßnahmen verpflichtet zu sehen.

Wer Marktwirtschaft mit hohem Wohlstandsniveau will, wird insbesondere unter verschärften Wettbewerbsbedingungen – China! – viel dafür tun, dass möglichst viele Ressourcen der Gesellschaft in die Lage versetzt werden, einen Beitrag zum Wohlstand zu leisten. Deshalb ist Befähigung, die mehr als nur formale Bildung umfasst, ein vorrangiges Thema. Es ist u. a. auch Befähigung zu mehr Kindern und zur Kindererziehung. Das muss die Gesellschaft, die Marktwirtschaft mit hohem Wohlstandsniveau will, auch wollen.

Menschen, die trotz aller derartigen Bemühungen unter das Existenzminimum fallen – ein Existenzminimum, das eine wohlhabende Gesellschaft relativ hoch ansetzen kann –, MUSS die Gesellschaft helfen.

Sie muss helfen, weil sie sich für die Marktwirtschaft und ihren Belohnungsmechanismus entschieden hat und daher auch Menschen in die Lage der Bedürftigkeit kommen lässt. Im Sozialismus gibt es keine DERARTIGE Bedürftigkeit, weil das SYSTEM keine Bedürftigkeit unter ihrem Wohlstandsniveau zulässt. Dass sozialistische Gesellschaften materiell arm sind, ist ein anderes Thema.

Entlang dieser Grundlinie kann man ohne Schwierigkeiten diskutieren. Die Frage, welche Vermögen und welche Vermögen gerecht oder ungerecht sind, ist irrelevant. Sie wird durch die auf parlamentarischem Weg mehrheitlich bestimmte Steuergesetzgebung beantwortet.

Es geht auch nicht mehr um Verteilungsgerechtigkeit, ausgenommen die EINE Frage:

Wie viel vom allgemeinen Wohlstand will die Gesellschaft an die Bedürftigen (unter dem Existenzminimum) abgeben?

Natürlich gibt es zu allem noch tausend Einzelfragen, aber viele der quälerischen, verworrenen Diskussionen wären überflüssig.

Sie wären natürlich auch dann überflüssig, wenn man sich auf ANDERE Ziele einigen würde.

An den Mitteln herumzuzerren, statt sich über Ziele zu einigen, ergibt ein Bild wie bei Max und Moritz auf dem Hühnerhof:

Zeitraubend, unergiebig, spaltend.

@ Dietmar Tischer

“Marktwirtschaft…verfügt … über die effizientesten und effektivsten Anpassungsmechanismen. ”

Das kann die Marktwirtschaft nur, wenn man sie lässt.

Die Marktwirtschaft lebt von Preissignalen an Produzenten und Kunden.

Signale dürfen nicht manipuliert werden, um richtige Entscheidungen zu bewirken.

Ich bin überzeugt, dass die Marktwirtschaft über Mechanismen verfügt auch absurd hohe Steuergesetzgebung und an die Wand gelaufene Kreditgeldsysteme in einem Markt zu überführen, in dem die Verbraucher zu leben haben. Warum? Weil die Marktwirtschaft ihre Menschen braucht, alle, ausnahmslos und mit jeder Qualifikation. Ohne Menschen kein Markt. Niemanden fallen zu lassen ist nicht nur christliches Bedürfnis sondern “menschliches” Erbgut – dabei will ich nicht behaupten, dass alle Zweibeiner auch Menschen sind (vgl. Kriegsverbrechen).

Das war in Zeiten von Slaverei und Feudalismus anders und diese Zeiten überwiegen die beiden Jahrhunderte von Aufklärung bis heute.

Obwohl ich verstehe wie Sie sich um Ausgleich bemühen, ist genau diese Konsensfindung und Erinnerung an gemeinsame Ziele ein Auslaufmodell.

Warum? Weil wir schon länger nicht mehr gefragt werden, wohin die Reise geht und sämtliche fragilen Sicherungssysteme in ihrer Existenz bedroht sind durch Entscheidungen, die unser Staat in seiner Konstitution unmöglich zulassen konnte.

Es passiert dennoch und die Gewaltenteilung erscheint offline, der Zustand der permanenten Krise ist zur Legitimation selbst geworden. Der Philospoph Bazon Brock (wer das Interview noch nicht kennt) https://youtu.be/52wplIxBH0o benennt das sehr treffend.

Daher würde ich den gemeinsamen Nenner nicht beim Wohlstand anlegen, sondern bei der Freiheit selbst.

Die (*) heilige Triade der Eigentumsökonomik, weil es kürzer nicht geht

• Eigentum und Recht werden zusammen geschaffen und

gehen zusammen unter

• Eigentum und Wirtschaft werden zusammen geschaffen und

gehen zusammen unter

• Eigentum und Freiheit werden zusammen geschaffen und

gehen zusammen unter

Eigentum bedingt Recht und Wirtschaft und Freiheit

(*) 66 Thesen zur Eigentumsökonomik, Prof. Otto Steiger

@ Alexander

>Obwohl ich verstehe wie Sie sich um Ausgleich bemühen, ist genau diese Konsensfindung und Erinnerung an gemeinsame Ziele ein Auslaufmodell.

Warum? Weil wir schon länger nicht mehr gefragt werden, wohin die Reise geht und sämtliche fragilen Sicherungssysteme in ihrer Existenz bedroht sind durch Entscheidungen, die unser Staat in seiner Konstitution unmöglich zulassen konnte.>

Ich bemühe mich zuerst um Klärung und dann auch um Verständnis für ein System, was ich für das bessere, ja sogar notwendige halte in unserer gegenwärtigen Lage.

Das gehört zur Diskussion, wie ich sie verstehe.

Zum anderen – nicht mehr Diskussion, sondern gesellschaftliches Problem, das zu Problemen in der Diskussionen führt:

Wir werden zwar um Zustimmung zu einer Reise gebeten, kümmern uns aber nicht sonderlich darum, zu welchem Ziel wir fahren, solange die Fahrt hinreichend komfortabel ist.

Das ist ein Fehler, die fortwährend für überflüssige Dissonanzen in der Gesellschaft führt.

>Daher würde ich den gemeinsamen Nenner nicht beim Wohlstand anlegen, sondern bei der Freiheit selbst.>

Marktwirtschaft impliziert Freiheit, BESCHRÄNKT sie aber auch durch die begrenzten Optionen, die sie bietet.

„Freiheit“ als Postulat im Sinne eines ZIELS kann auch kontraproduktiv sein, weil man damit u. a. im Libertarismus extremer Ausprägung wie „Anarchokapitalismus“, bei dem die Grenzen zwischen dem klassischen Liberalismus und dem Anarchismus geschleift werden, zu letztlich nicht funktionalen Zuständen kommen kann.

So gibt es Anhänger dieser „Gesellschaftsordnung“, die z. B. die Verteidigung gegen externe Angriffe auf rein marktwirtschaftlicher Basis befürworten.

Da kann es dann mit der Freiheit, auch einer Minimalfreiheit sehr schnell vorbei sein.

@ Dietmar Tischer

“Freiheit ist das höchste politisch Ziel.”

Lord Acton

Um die Grenzen von Freiheit braucht man sich nicht zu sorgen und Hinweise auf Anarchokapitalismus sind missverständlich, weil Anarchie mit Anomie verwechselt wird. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anomie

Nach der Dysfunktion von Preisfindung aus den Komponenten Zins, Nachfrage und Bonittät für staatlicher Schuldner, war diese Woche hier im Bliog der nächste Stein der Dominoralley – die Rente – Diskussionsthema.

Rentenversicherer sind auf sichere Anlagen angewiesen und das sollen Staatsanleihen nun einmal sein. Herr Stöcker monierte das Problem privater Halter, die noch nicht ausgegrenzt sind…und einen Markt darstellen. Nullzins ist noch zu hoch? “Geld muss rosten”.

Ich stelle nicht die Notwendigkeit von Rente und Versorgung in Frage, aber es ist klar, dass es keine Anlageform für Sparer mehr gibt und das Rentensystem auf Umlagebasis in Kürze scheitert. (vgl. H.W.Sinn – 32 Mio zusätzliche Beitragszahler bis 2035 nötig).

Welche Freiheit werde ich als Rentner haben, wenn mein Arbeitsleben aus Deflationsdruck von Globalisierung (Einkommenstillstand), Vermögenspreisfinlation (Miete, Wohneigentum) und – keine Sparmögllichkeit – dominiert wird?

Während sie sich zu Recht Gedanken machen, dass unser Gemeinwesen nicht vor die Hunde geht, ist mir klar, dass ich kein Leben im Alter werde führen können. Schon gar kein selbstbestimmtes.

Dabei werden mir politische Zwänge präsentiert, die jeden Widerspruch verbieten. Man wird in bester Manier diffamiert, ausgegrenzt, als Looser oder einfach nur als Depp tituliert. (vgl. Stöcker – Wettbewerb for loosers). Probieren sie es selbst aus und ergreifen sie bei einer Partei ihrer Wahl das Wort….egal welche.

Mit ihrem Eingangsstatement (zitert von mir), werden sie bei jeder Partei aus dem Saal getrieben. Der Konsens ist längst bei Staatswirtschaft und Planwirtschaft angelangt.

Als ich gestern kommentierte #wir sind Zombie….war das keine Ironie.

@ Alexander

Freiheit kann unter den heutigen Bedingungen nicht das höchste politische Ziel sein.

Der Wohlstand ist das entscheidende Kriterium, das über Stabilität von Gesellschaften wie unserer entscheidet.

Und Freiheit als höchstes politisches Ziel GARANTIERT nicht hinreichend hohen Wohlstand.

Dass wir MEHR Freiheit haben sollten in unserer Gesellschaft, auch um mehr Wohlstand zu erzielen, ist unstreitig zwischen uns, aber ein anderes Thema als das, um das hier geht – die Voraussetzungen von Diskussion, die KLÄREN will.

Dazu:

Wenn schon „Freiheit“, dann die Freiheit der Marktwirtschaft, die ich als Mittel zu hinreichend hohem Wohlstand ansehe.

Warum:

In der Marktwirtschaft wird Freiheit OPTIMAL verwirklicht, weil sie idealtypisch nur durch FREIHEITLICH handelnde Menschen und nichts anderes begrenzt wird.

Aber:

Der Markt kann nicht alles lösen, z. B. nicht für eine effektive Verteidigung sorgen.

Daher muss die Marktfreiheit da begrenzt werden, wo sie das Erforderliche nicht leisten kann, u. a. auch die Verteilung von Wohlstand an andere, die das Existenzminimum nicht erreichen.

Aber eben nur DA.

Kurzum:

Der BEGRENZTEN funktionsbezogenen Reichweite einer an sich optimal freiheitlichen Marktwirtschaft wegen kann Freiheit nicht das höchste politische Ziel sein.

Unabhängig von der Wohlstandsprämisse, die auf dem Erfordernis einer stabilen Gesellschaft unter HEUTIGEN Bedingungen basiert, ist dies, auf dem Regelsystem der Marktwirtschaft beruhend, die argumentative Begründung dafür, warum Freiheit, als maximale individuelle Freiheit verstanden, nicht das HÖCHSTE politische Ziel sein kann.

@ Dietmar Tischer

Ich verstehe sie besser, als sie es für möglich halten.

Ihre Beispiele sind Maßstab für eine Zeit, die zu Ende geht. Ich würde diese Phase als sozialdemokratisches Zeitalter bezeichnen, vgl. Rolf Peter Sieferle “finis BRD” und sie endet an der Unfinanzierbarkeit ALLER Versprechen, nicht nur der Mindestsicherung.

Die Versprechen werden gebrochen im Zuge des Euroendes, target2 Verlusts mit vorherigen oder nachfolgenden Staatspleiten in Europa und der Welt.

Das exportorientierte Geschäftsmodell der BRD ist am Ende und Berlin sorgt zuvor noch für “schöpferische Zerstörung” (Stöcker) an seinen Schlüsselindustrien.

Woher Beitragsströme finanziert werden sollen, wenn die Einnahmen wegbrechen kann später nur die #whatever it takes Zentralbank erklären.

Es gibt keine Marktwirtschaft ohne FREIE Preisfindung, jede Manipulation verzerrt den Markt bis zur Funktionsunfähigkeit=Dysfunktion.

Dysfunktion drückt sich in dem 200 Jahrezinstief für italienische Staatsanleihen aus und zieht sich durch alle Finanzierungen Italiens…..als Refinanzierungen unterhalb der Rentenpapiere.

Lösung – keine.

Meine Erkenntnis ist, dass je länger wir diesen Zustand der Insolvenzverschleppung fortsetzen, je weniger wir per “Demokratie in Freiheit” zu entscheiden haben, wenn es zum Spruch kommt.

Jedes Grundrecht, das im Zuge diverser Rettungen abgetragen wird, hat seine Schutzfunktion für den Konkurs verloren. Es gibt schon jetzt keine Möglichkeit mehr gegen völkerrechtswidrige Entscheidungen juristisch vorzugehen, ohne zur Zielscheibe zu werden…..Demokratie, Freiheit, Rechte…..passé.

Gehen sie gerne auf meine Punkte zu Staatsanleihen, Rente, Grundrechten ein und schauen sie sich die heilige Triade der Eigentumsökonomie in Ruhe an. Darum dreht sich meine Position, um nichts weiter.

Freiheit ist kein Privileg für einzelne, sondern ein Grundrecht für alle – oder es ist keine.

Freiheit von Zwang – Freiheit für (Eigen-)Verantwortung.

… ist mein Rezept für die Zeit danach….

@ Alexander

Ich denke, dass die Übertreibung und Zuspitzung der ökosozialistischen Ideologie die notwendige Voraussetzung für den zeitnahen Absturz derselbigen ist.

Der normale Bürger kann doch diesen ganzen Klimascheiß schon nicht mehr hören.

Es ist wie an der Börse:

Die Hausse stirbt in der Euphorie, dem festen Glauben, dass jetzt alles möglich ist.

In Wirklichkeit malen sich die Ökobewegten die Zielscheibe für die Sündenbockrolle des unvermeidlichen Wirtschaftsabschwunges auf die Stirn.

Die Arbeitslosen werden sich schon erinnern, wer für die Zerstörung ihrer wirtschaftlichen Existenz verantwortlich ist, gerade deswegen, weil dieses Thema jetzt so dominant in den Medien ist.

@ikkyu

Ja, die ökosozialistische Propaganda ist extrem aggressiv und fällt dummerweise auch noch mit dem Eintritt Deutschlands in die Rezesson zusammen. Sehr schlechtes Timing, da waren die Grünen und ihre Hofschranzen einfach zu gierig und zu berauscht von den Umfragewerten.

Haben Sie eigentlich den netten Jakob bei “Hart aber Fair” diese Woche gesehen, der auch das freitägliche Schulschwänzen fürs Klima mit organisert? Ein ganz normaler junger Mann, eine echte Stimme des Volkes – und gleichzeitig zufällig Beisitzer im Vorstand bei der Grünen Jugend Kiel, was natürlich nicht im Fernsehen erwähnt zu werden braucht: https://www.instagram.com/p/Br5gkg9ntLD/

@ ikkyu

Auch eine private genossenschaftliche Gesundheitsversicherung weist sozialisitische Merkmale auf, die allen Kollektivismen gleich sind. Ich will die Vorzüge von Arbeitsteilung und “freiwillig” (!) gemeinschaftlich getragenenn Risiken auch gar nicht in Abrede stellen.

Deshalb ist mir der Ausdruck Ökosozialismus zu verharmlosend für eine Ideologie, die absolut zerstörerisch unserer Gesellschaft ihre Wohlstandsgrundlage entziehen will. Ähnlich hintertreiben dieselben Charaktere andere Nationen wie in Kanada, USA, Schweden, Frankreich, Italien…

Beispiel: Als Imker setze ich mich für Umweltschutz ein und nehme auch gegen Mandatsträger kein Blatt vor den Mund. Den Zirkus um das Volksbegehren Artenvielfalt in Bayern nutzen ausgerechnet örtliche Kommunisten für ihr Engagenemt, aber keine Imkervereine. Es ist wieder so eine Aktion, der man sich noch anschließen darf, deren Inhalte andernorts schon bestimmt waren..

Als Imker bin ich gegen die exzessive Landwirtschaft und angesichts der Nullzinsfinanzierungsgeschenke, könnten die Landwirte noch stärker subventioniert werden um weniger Chemie auszubringen…wenn schon, dann konsequent, aber der Zwang gegen Landwirte soll ihre Unternehmung zerstören.

Obwohl wir eine buchhalterisch/debitistische Finanzierungskrise haben sehe ich sehr wohl, dass man diese Krise als Chance nutzt um Politik zu machen. Nicht nur Geopolitik, sondern Politik gegen Eigentum/Privatwirtschaft und die sich daraus ableitende Freiheit. Das Leben ist jetzt schon so teuer, dass der normale Mensch kaum über die Runden kommt, obwohl wir historisch einmalig hohe Wertschöpfung und Produktivität schaffen. Hier stimmt etwas anderes nicht und das Phänomen kein nationales.

Allerlei Schuldgefühle schaffen die Zustimmung der Wähler für ihre eigene “Versklavung” und “Abschaffung”, während sich zeitgleich feudale Strukturen unkontrolliert ausprägen – “tina!.

Wenn sich Kinder über ihre bloße Existenz schuldig fühlen, hört bei mir jede Toleranz auf. Ich will keine Tatsachenwahrheit leugnen, aber was Tatsache ist erzählt mir kein von wem auch immer “ernannter Wissenschaftler” im Auftrag meiner Abschaffung.

“„How Low Will The S&P Go? Buffett & Shiller Know…“

Die FAANG Aktien + Microsoft verzerren alle theoretischen Berechnungen.

Alleine Amazon und Apple haben zusammen eine Mcap, die dem DAX + MDAX ungefähr entspricht.

Wenn man zukünftig negative Renditen für den US Aktienmarkt vorhersagt, dann ist es eine Wette gegen FAANG und Microsoft. Kann man machen und kann auch stimmen…

Nur als Basis für die Vorhersage z.B. des Verhältnis Mcap/ USA BIP (Buffet-Indikator) zu nehmen, macht aufgrund der WELTWEIT dominanten Stellung dieser Unternehmen m.E. wenig Sinn.

Man müsste stattdessen davon ausgehen, dass es mehr Konkurrenz für diese Unternehmen gibt und entsprechend die Margen zurückgehen oder aber sich die Internetnutzung weg von Facebook, Netflix bewegt. Bzgl. der Margen bei Apple sicherlich ohne Probleme möglich.

Aber bei Amazon, Alphabet/Google, Facebook, Microsoft müsste schon etwas wesentliches passieren, damit die ihre Marktstellung verlieren.

In trockenen Tüchern ist für mich deshalb eine negative Entwicklung der US Aktien in den nächsten Jahren immer noch nicht. Noch nicht einmal eine Underperformance in den nächsten Jahren gegenüber anderen Märkten. Trotz aller Kennzahlen.

Jüngere Menschen verzichten eher auf ein Auto etc. als nicht mehr die o.a. Unternehmen zu nutzen. Egal was man selbst von dieser Entwicklung hält…

Eine Zerschlagung der Konzerne wäre eine Variante…

Marktanteil bei PC-Betriebssystemen von Microsoft und MAC OS lt. Statista: 98%

Google Anteil bei Suchmaschinenanfragen per 2017 weltweit 92%.

Aber wir wettbewerbsfreudigen Europäer mit unseren alten Industrien untersagen eine Fusion von Siemens und Alstom im Bahnbereich. Das ist sicherlich grundsätzlich richtig, aber eben nur, wenn man auf dem anderen Auge bzgl. Marktmacht von US-Unternehmen nicht blind wäre bzw. handeln könnte.

@Ikkyu:

Die Welt geht oekologisch vor die Hunde. Daran aendert das Gefühl der Übertreibung gar nichts.

Was nervt ist, dass suggeriert wird, dass wir nicht verzichten müssen und dass das Thema (Umweltschutz) teilweise völlig widersinnig bei konträr stehenden Produkten als Marketingargument benutzt wird.

Vor allem in Deutschland wird oft um drei Ecken gedacht.

Ähnlich ist die völlig verquere Denke “wenn ich Lohnzurückhaltung übe, dann geht es meinem Arbeitgeber gut und ich werde mehr verdienen”.

@Markus:

“Die Welt geht oekologisch vor die Hunde.” –> Haben Sie dafür auch Belege?

Selbst, wenn die Welt ökologisch vor die Hunde geht: Meinen Sie im Ernst, dass Deutschland mit seinen 80 Mio Einwohnern, die bald-8-Milliarden-Menschen-Welt rettet, oder mit seiner spinnerten Umweltpolitik (insbesondere Energie) auch nur von irgendjemandem als Vorbild angesehen wird?

@Markus:

“Die Welt geht oekologisch vor die Hunde. Daran aendert das Gefühl der Übertreibung gar nichts. Was nervt ist, dass suggeriert wird, dass wir nicht verzichten müssen”

Sie können ja nach China oder Indien gehen und dort die Notwendigkeit zum Verzicht predigen. Glauben Sie, irgendjemand wird Ihnen folgen?

Wenn Sie tatsächlich glauben, dass die Welt in einem ökologisch so schlechten Zustand ist, dann sollten Sie besser Technologien entwickeln und Maßnahmen planen, mit denen wir uns zum Beispiel an künftige Klimaveränderungen besser anpassen können und trotzdem unseren Lebensstandard weiter steigern können. Dieser Gedanke läuft natürlich dem grünen Flagellantentum komplett zuwider, aber mit solchen Vorschlägen könnten Sie auch in China oder Indien etwas verändern.

@ Markus

Wenn die wirtschaftlichen und sozialen Folgen der deutschen Umweltpolitik spürbar werden, wird sich das Klima in der Gesellschaft um 180° drehen.

Dann werden wieder Politiker gewählt, die sich um eine kostengünstige Energieversorgung und Arbeitsplätzen kümmern und nicht die Rettung der Welt vor einer imaginären Klimakatastrophe als Hauptagenda verfolgen.

Die Bevölkerung hat ja jetzt schon ganz andere Sorgen, obwohl der Abschwung noch gar nicht begonnen hat.

https://www.ruv.de/static-files/ruvde/downloads/presse/aengste-der-deutschen/grafiken/StaticFiles_Auto/ruv-aengste-plaetze-1-10.jpg

@ ikkyu

Bin ganz Ihrer Meinung.

Ich glaube auch, dass dann Schülerinnen und Schüler nicht mehr protestieren, sonder im Unterricht 2 x 2 = 4 lernen, werden weil dies zu wissen besser für Ihre Zukunft ist, als unfruchtbare Rettungsparolen in die Welt zu rufen.

@meine Kommentatoren:

Ich hatte nicht gesagt, dass die jetzige Politik irgendetwas richtig macht hinsichtlich der Umweltpolitik. Ich hatte geschrieben, die Umweltprobleme sollten nicht verharmlost oder negiert werden.

Ich halte es nicht für sinnvoll Diesel zu verteufeln und Benziner zu pushen, die mehr CO2 produzieren. Ich halte nichts davon Elektromobilität ohne Konzept (Ladeinfrastruktur) zu pushen. Ich denke, es war sehr unklug erst Photovoltaik zu fördern und dann, kurz vor der Wirtschaftlichkeit, die Förderung stark zurückzufahren, damit chinesische Hersteller übernehmen. Ich halte nichts von überstürzter Abschaltung von Atom- oder Braunkohleelektrizitätswerken.

ABER:

– Wir sind in der Nähe von Peak-Öl. Es wird in Zukunft immer mehr Energie benötigt werden, um Öl aus dem Boden zu bekommen.

– Es GIBT den Klimawandel

– Es GIBT Umweltprobleme

@ Markus

Die FUNDAMENTALE Kritik:

Es gibt IMMER Probleme, d. h. Situation, die wir so nicht hinnehmen wollen, weil sie unserem Wohlbefinden – verstanden in einem weiten Sinne – schaden oder gar unsere Existenz bedrohen.

Wir haben als vernünftige Wesen die Fähigkeit, die Möglichkeiten von Veränderung zu erkunden, die Kosten – wieder in einem weiten Sinne verstanden – uns für Maßnahmen zu entscheiden und entsprechende in Gang zu setzen.

Darüber gibt es keinen PRINZIPIELLEN Disput und das tun wir auch regelmäßig.

ABER:

Was ist mit den Problemen, für die es ERKENNTLICH keine Lösung gibt?

Ohne über die Daten und Fakten zu streiten, nehme ich jetzt einmal mit Ihnen an, dass es einen der Menschheit schadenden Klimawandel gibt.

Wenn wir nun feststellen, dass der größte Teile der Menschheit nichts gegen ihn tut, sondern ihn im Gegenteil kontinuierlich beschleunigt, was tun wir dann?

Setzen wir unsere Ressourcen für ein definitiv durch UNS nicht erreichbares Ziel ein oder geben wir es auf und lassen, was uns betrifft, den Klimawandel geschehen?

Welche der beiden Optionen ist RATIONAL?

Für vernünftige Menschen ist klar, dass wir den Klimawandel geschehen lassen sollten.

Jetzt kommen aber die ÜBERVERNÜNFTIGEN und sagen:

Wenn wir mit gutem Beispiel vorangehen, werden sie uns folgen und der Klimawandel kann verhindert werden.

Was ist daran richtig oder falsch?

Weder das eine noch das andere, weil es die Zukunft betrifft, die wir nicht kennen können.

Wir wissen aber, wie in der Menschheitsgeschichte seit eh und je verlaufen ist:

NIEMAND hat sich jemals für ein übergeordnetes GANZES engagiert, wenn ein derartiges Engagement sich gegen die eigenen als Ziele richtete.

Das ist auch heute der Fall:

Die Bevölkerungen Chinas, Indiens, Russlands etc. wollen materiell reich werden. Ob das dumm oder klug ist, sei dahingestellt. Sie WOLLEN es und wenn sie dafür viel CO2 produzieren, werden sie viel CO2 produzieren. Deutschland und niemand sonst wird sie davon abbringen können, weil das für sie hieße: Die wollen unseren Wohlstand verhindern.

Kurzum:

Es ist reines WUNSCHDENKEN zu glauben, dass wir nur mit gutem Beispiel vorangehen müssten und uns dann die Welt folgen würde.

Stattdessen EVOLUTION denken:

Es gab schon immer Entwicklungen, die Arten ausgelöscht haben.

Das ist einfach nur NORMAL.

@DT:

So kann man argumentieren. Ich halte es nur für gefährlich, wenn Leute vom “angeblichen Klimawandel” reden, genauso wie ich es für gefährlich halte, wenn Menschen davon reden, dass “angeblich Arme in Deutschland gibt.” Den Klimawandel halte ich, neben der wieder auflackernden dritte Weltkriegsgefahr, für sehr gefährlich für das Überleben der Menschheit. Und ich bin nicht völlig bei Ihnen: es gibt Normen und Altruismus in der Welt. Und es gibt Vorbilder. Andererseits muss ich zugeben, dass zur Zeit viele Deutsche unglaublich naiv sind, die Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands maßlos überschätzen und nicht für die Zukunft planen.

@ Markus

Wenn man die Argumentation als nicht widerlegt oder nicht widerlegbar akzeptiert, muss man – Rationalität unterstellt – auch die Schlussfolgerung akzeptieren.

Mit Blick darauf ist es NICHT „gefährlich“ – Sie meinen vermutlich kontraproduktiv – vom „angeblichen Klimawandel zu reden.

Denn ob es, wie in meiner Argumentation angenommen, einen tatsächlichen gibt oder keinen, ist unerheblich. Denn die Schlussfolgerung, mit der Energiewende dagegen vorzugehen, ist so oder so nicht rational (allerdings mit jeweils anderer Begründung).

Sie haben recht:

Wenn es den Klimawandel tatsächlich gibt, ist er sehr gefährlich für das Überleben der Menschheit oder zumindest sehr vieler Menschen.

Gibt es ihn nicht, spielt er keine Rolle für das Überleben der Menschen oder nur insoweit, wie zu viele annehmen, dass es ihn gibt und daher Ressourcen eingesetzt werden für etwas, das nicht erforderlich ist.

>Und ich bin nicht völlig bei Ihnen: es gibt Normen und Altruismus in der Welt>

Selbstverständlich gibt es Normen und es gibt Moral. Ich erwarte und fordere daher immer wieder, mitunter auch an diesem Blog, dass sich Menschen dazu bekennen, was sie davon abgeleitet, als Ziel für die Gesellschaft wünschen.

Und selbstverständlich gibt es Altruismus in der Welt.

Meine Argumentation verbietet nicht, altruistisch zu handeln.

Wenn wir z. B. irgendwann Wasser im Überfluss haben und in Afrika mangelte es davon, hätten wir die Pflicht uneigennützig zu helfen.

Dies völlig unabhängig davon, ob es den Klimawandel gibt oder nicht.

@Markus und DT:

“Und selbstverständlich gibt es Altruismus in der Welt.”

Man sollte sich unbedingt die Frage stellen, warum ausgerechnet diejenigen, die den menschgemachten (!) Klimawandel propagieren, altruistisch handeln sollen, was sie ja mindestens implizit vorgeben. Liegt Ihnen tatsächlich am Wohl der Menschheit (= Allgemeinheit), oder handelt es sich nur um ein (gigantisches) Geschäftsmodell für die Politik und Teile der Wirtschaft? Oder ist diese Propaganda nur Angstmacherei, um die Gesellschaft in einen Ablasshandel zu zwingen und im Sinne einer Ideologie zu “transformieren”? https://conservo.wordpress.com/2019/02/07/die-grosse-transformation-ade-freiheit/#more-23492

Eine grundsätzliche Kernfrage ist immer: Warum sollte man anderen Leuten, die man nicht kennt (insbesondere Politiker), die aber auf das eigene Leben wie auch immer Einfluss nehmen wollen, vertrauen? Die Frage wird umso virulenter, wenn es darum geht, dass diese fremden Leute sich anmaßen, fremder Leute, also auch von einem selbst erwirtschaftete Mittel, per staatlichem Zwang zu enteignen und nach eigenem Gutdünken umzuverteilen. Und zwar insbesondere auch zur Aufrechterhaltung ihres eigenen, weitgehend überflüssigen Politikbetriebes, der Grundlage des Erwerbs ihres (parasitären) Lebensunterhalts ist.

@ SB

Sie verkennen, was „Altruismus“ meint.

Er ist uneigennütziges, selbstloses Handeln angesichts der SITUATION (Notlage) eines anderen, ohne mit Blick darauf, wie dieser sich in der Vergangenheit verhalten hat und sich in der Zukunft verhalten wird.

Ihre kalkulatorischen Überlegungen greifen also nicht – erst einmal.

Es kann aber durchaus sein, dass man altruistisches Handeln ändert, wenn erkennbar ist, dass die Hilfe, die man gewährt, bewusst (wissentlich) immer wieder zum KONTINUIERLICH Schlechteren missbraucht wird. Gewährte man in diesem Fall weiterhin Hilfe, dann würde man einen Beitrag zu SCHÄDIGUNGEN – vielfach auch anderer – leisten. Das kann nicht verlangt werden, dazu kann man nicht verpflichtet sein.

„sind wir doch die großen Verlierer des Euro-Endgames“

Hier wurde gestern einer der Hauptschuldigen für seine „Verdienste“ um das Euro-Austeritätsdesaster geehrt. Wie hatte bereits Hellwig in der TARGET-Debatte geschrieben: Si tacuissent… Das gilt dann wohl auch für Alesina und Bernau: https://blogs.faz.net/fazit/2019/02/06/wann-austeritat-funktioniert-10510/

Ich habe vor Ort dazu Skidelsky und Wyplosz verlinkt.

LG Michael Stöcker

@Herrn Stöcker:

Lieber Herr Stöcker, Sie sind wesentlich belesener und tiefer in der Materie drin als ich, aber wenn ich Ihren Debattenbeitrag so lese, kommt mir der oben zitierte Warren Buffet in den Sinn. Er hatte einmal mit einem Diskussionspartner zu tun, der ähnlich tiefschürfend und ausführlich argumentiert hat wie Sie. Buffet hat ihn ausreden lassen und ihm dann nur mit einer Gegenfrage geantwortet:

“If you are so clever, why aren´t you rich?”

Dem möchte ich nichts hinzufügen. Herr Dr. Stelter kann für sich selbst sprechen.

Sorry, da hat aber Warren Buffet was selten dämliches gesagt. Ich würde behaupten, dass der Großteil der wirklich cleveren Leute nicht als Hauptziel Reichtum hat.

Dann möchte ich Ihnen auch mit einer Gegenfrage antworten, Herr Selig:

Ab welchem Geld- und Sachvermögen und/oder Anzahl an Kindern und Enkelkindern gilt denn bei Ihnen jemand in Deutschland als reich?

LG Michael Stöcker

“Ich würde behaupten, dass der Großteil der wirklich cleveren Leute nicht als Hauptziel Reichtum hat.”

Das spielt keine Rolle, da es nicht darum geht, wonach clevere Menschen streben, sondern darum, welche Teilmenge der nach Reichtum strebenden Menschen damit erfolgreicher als die Restmenge ist.

Wenn bei einer hinreichend grossen Stichprobe die “Cleveren” im Vermögensaufbau nicht erfolgreicher als die “Übrigen” sind, würde ich die Definition von “clever” hinterfragen. Wobei ich nicht von vorne herein ausschliessen möchte, dass die beiden Grössen “Cleverness” und “Vermögen” nicht oder nur wenig miteinander korrelieren.

Warren Buffet, sollte das Zitat tatsächlich von ihm stammen, würde ich insofern zustimmen, dass der überwiegende Teil der Menschen sich für cleverer als der Durchschnitt hält. Bei der Vermögensverteilung sehen sich die meisten Menschen jedoch auf der völlig falschen Seite der Paretoverteilung. Beides weisst darauf hin, wie wichtig die Auswahl der Stichprobe ist, wenn man ein Ergebnis bekommen will, dass einem in den Kram passt.

@ mg

Und wie schätzen Sie die Verteilung der Bundesbank ein (Seite 65)? https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/604904/bb345ad5999c923eebdbd4fcce69914d/mL/2016-03-vermoegen-finanzen-private-haushalte-data.pdf

LG Michael Stöcker

@Markus: Ich denke, “clever” ist nicht klug oder weise. Dann würde ich Ihnen recht geben. Aber hier kann man natürlich über Begrifflichkeiten streiten bzw. über die korrekte Übersetzung.

@Michael Stöcker:

Das ist eine philosophische Frage, die sich m.E. nicht in € oder in einer konkreten Kinderzahl beziffern lässt und für deren Beantwortung mir die Worte schwer fallen; ich versuche es trotzdem. Und diese Frage trifft auch überhaupt nicht die Zielsetzung meines vielleicht zu emotionalen bzw. diesbezüglich zu sehr um die Ecke gedachten Beitrags. Denn mir ging es bei dieser Bemerkung nicht um finanziellen oder familiären, sondern um intellektuellen Reichtum. Und zwar ausschließlich.

Ich versuche mich mal, dem Thema anzunähern:

Wikipedias Aussage zu Ihrer Frage:

“Personen mit mehr als 200 % des äquivalenzgewichteten mittleren Einkommens leben in Einkommensreichtum. Diese Grenze wurde von Ernst-Ulrich Huster vorgeschlagen. Zwischen 1998 und 2004 betraf dies in Deutschland je nach Jahr und Quelle zwischen 5 % und 9 % der Bevölkerung.”

Keine Ahnung, ob das auf Sie zutrifft; es interessiert mich (und vermutlich auch die Leser dieses Blogs) ehrlich gesagt nicht wirklich und war nicht der Auslöser für meinen Beitrag.

Von Kinderreichtum spricht man laut der gleichen Quelle in Deutschland ab 4 eigenen Kindern. Und je mehr Kinder, umso höher die Wahrscheinlichkeit bzgl. einer größeren Zahl von Enkeln. Das würde mich zum besseren Verständnis Ihrer Beiträge schon eher interessieren, aber es geht mich ehrlich gesagt überhaupt nichts an, denn es ist Ihre Privatangelegenheit und daher frage ich auch nicht nach.

Was für mich der Punkt war: Ich verfolge seit längerer Zeit diesen Blog und beteilige mich regelmäßig mit manchmal mehr oder manchmal auch weniger gelungenen Beiträgen daran, wenn ich die Reaktionen von Hr. Dr. Stelter und anderen regelmäßigen Foristen wie Herrn Tischer richtig interpretiere. Andere tun dies in unterschiedlicher Intensität ebenfalls. Die meisten von uns versuchen es aber zu vermeiden (und hier zähle ich mich dazu, vielleicht nicht immer mit Erfolg), bekanntere Persönlichkeiten aus Wissenschaft, Wirtschaft, Medien oder Wirtschaftsforschung (ausgenommen Politiker) mit den von Ihnen gestern getätigten Bemerkungen wie “si tacuissent” oder “Hauptschuldigen” zu belegen. Weil wir selbst auf der Suche nach Lösungen oder auch am Austausch von kontroversen Ansichten interessiert sind, um die eigene Meinungsbildung weiter zu formen, die eben noch nicht abgeschlossen ist. Und das möchte ich selbst “großen” Namen zubilligen. Bei Ihnen habe ich durch solche Bemerkungen regelmäßig den Eindruck, dass Sie das missbilligen, da Sie selbst die Äußerungen solcher Leute schon als falsch erkannt haben und zumindest in meiner Wahrnehmung den Eindruck vermitteln, die Lösung für alle geldpolitischen Probleme schon zu haben und es daher für unnötig halten, dass solche Leute längst selbstverständliche Erkenntnisse durch von Ihnen als falsch erkannte Äußerungen noch in Frage stellen.

Sir Karl Popper sagte uns dazu mal bei einem seiner Vorträge Anfang der 90er sinngemäß, dass man in der Wissenschaft nichts verifizieren, sondern nur falsifizieren kann und die eigene These daher nur vorläufig als richtig gelten kann, bis sie beispielsweise von jemand anderem empirisch oder anderweitig widerlegt wird.

Sie sind meiner Meinung nach reich an Kenntnissen, Zitaten, Quellen und Aktivitäten. Aber – nichts gegen die Arbeit von Herrn Dr. Stelter – das ist hier ein relativ exotischer Blog für wenige an Geldpolitik interessierte Leute aus dem deutschsprachigen Raum. Wenn Sie wirklich glauben, Leuten wie Herrn Prof. Sinn und anderen in einer ähnlichen medialen Gewichtsklasse geldpolitisch bzw. intellektuell deutlich überlegen zu sein (worüber ich mir ein Urteil nicht anmaßen möchte), müssten Sie m.E. – ähnlich wie Hr. Dr. Krall, Hr. Dr. Stelter oder der von den meisten von uns nicht gerade geliebte Prof. Fratzscher es gerade tun – die intellektuelle Nische verlassen und auf der großen Bühne reüssieren und Leute überzeugen, um die Situation wirklich nachhaltig zu verbessern. Für Ihren Blog “zinsfehler.com” betreiben Sie nach meiner Wahrnehmung einen ungeheuren intellektuellen und zeitlichen Aufwand; das ist in hohem Maße anerkennenswert. Mir fehlt dafür Zeit, Kraft und evtl. auch die Intelligenz. Ich trete Ihnen aber hoffentlich nicht zu nahe, wenn ich vermute, dass Sie damit die europäische Geldpolitik bisher nicht maßgeblich beeinflusst haben, da das Netz bei der Suche Ihres Namens v.a. den verstorbenen früheren Oberbürgermeister der Stadt Rosenheim benennt. Ich will Sie mit dieser Bemerkung nicht verspotten, sondern ernsthaft zum Nachdenken anregen, weil m.E. niemand, der so viel Zeit in das Thema investiert wie Sie, nur am eigenen Wohlergehen interessiert ist, sondern immer auch in bester römischer Tradition die “res publica” im Auge hat. Davon gibt es wie so oft viel zu wenige Leute, Sie sind sicher einer davon. Eventuell wäre aber eine Vereinfachung Ihrer Sprache, verbunden mit Überzeugungsarbeit bei breiteren Bevölkerungsschichten, ein besserer Weg zur Umsetzung einer gerechteren Geldpolitik.

Und wenn Sie jetzt fragen, warum ich um diese Uhrzeit solche epischen Kommentare verfasse, kann ich nach etlichen Monaten auf diesem Blog nur antworten:

Hier stehe ich. Ich kann nicht anders. Amen (Martin Luther zugeschrieben)

Denn das Internet verleitet dazu, einen selbst irritierende Aussagen zu ignorieren und aus Bequemlichkeit wegzuklicken, bei denen man im persönlichen Gespräch mit dem Nachbarn über den Gartenzaun eher zu diskutieren beginnen würde und das wollte ich hiermit mal tun. Ich verspreche Ihnen aber, dass das letzte Mal war und ich mich nur mehr Hr. Dr. Stelters Beiträgen widmen werde, denn er hat m.E. ein moralisches Recht darauf, dass sich die Foristen mit seinen Themen beschäftigen oder sich alternativ einen anderen Blog suchen bzw. einen eigenen starten. Und dieses moralische Recht will ich ihm (mit der heutigen Ausnahme) nicht streitig machen.

@ms

Perzentile sind Ausreissern gegenüber sehr rubust.

Folglich werden Sie das Vermögen der 1% in dieser Darstellung, selbst wenn mit einer Lupe bewaffnet, kaum wiederfinden. Ein Schelm wer Böses dabei denkt.

robust ;-)

Auch wenn ich einen vermutlich grossen Teil Ihrer Ansichten nicht teile, so empfinde ich Ihre Beiträge – und die von Herrn Seelig – als die einzigen, dauerhaft lesenswerten. Es steht jedem frei, die eingestreuten Spitzen zu überlesen.

@ mg

Ich finde mich ja noch nicht einmal selber wieder. Interessant wäre das letzte 1 % unterteilt in Perzentile, so dass die 0,01 % zum Vorschein kämen. Ich vermute, dass es dann am oberen Ende doch sehr exponentiell wird, wenn auch von Kladden, Heister, Schwarz & C0. berücksichtigt würden. Aber so weit geht die Offenheit dann doch nicht, bzw. man muss sie sich selber zusammen reimen.

LG Michael Stöcker

Würde mich sehr wundern, wenn der Grafik keine Paretoverteilung zu Grunde liegen würde. Wenn man die P99 oder die P99,9 dort eintragen würde, müsste man für die y-Achse vermutlich eine logarithmische Darstellung wählen und die kleineren Vermögen wären trotzdem kaum zu sehen.

Dass Sie sich in keinem der dargestellten Perzentilen wiederfinden, überrascht mich dann doch. ;-)

Kurz nochmal zur “Cleverness”: ich nehme an, dass diese Eigenschaft bei den vermögenden Topprozent ebenfalls einer Normalverteilung unterliegt, möglicherweise mit einem nach rechts verschobenen Median (was natürlich nichts mit der politischen Orientierung zu tun hat ;-) ) und einer schmaleren Standardabweichung. Obwohl, wenn ich mir die Spezialauftritte von Herrn Trump so angucken, vielleicht auch mit einer breiteren Standardabweichung. *g*

Die deutschsprachige Wikipedia schreibt nun zur Paretoverteilung: “Pareto-Verteilungen finden sich charakteristischerweise dann, wenn sich zufällige, positive Werte über mehrere Größenordnungen erstrecken und durch das Einwirken vieler unabhängiger Faktoren zustande kommen.”

Das spricht weitestgehend fùr sich. Die von Ihnen vorgeschlagene Erbschaftssteuer, selbst wenn sie weltweit durchgezogen würde, würde an einer Paretoverteilung der Vermögen vermutlich lediglich die Steilheit ändern. Möglicherweise würde sich ein Grossteil der Menschen, die sich unterhalb der P70 wiederfinden, unverändert benachteiligt fühlen, während sich 90% der Menschen in Sachen “Cleverness” klar bevorteilt (nicht übervorteilt!) fühlen dürften.

Also vom philosophischen Standpunkt azs gesehen, muss das eine dieser merkwürdigen Paradoxien des Lebens sein.

@ms

eigentlich verwunderlich, dass im anglesächsischem Kulturkreis die Spaltung zwischen arm und reich regelrecht obszön ausfällt, Neid und Missgunst aber eher ein Problem in Deutschland und Frankreich zu seien scheint, siehe z.B.

http://www.spiegel.de/plus/millionaere-in-deutschland-der-reichtums-report-a-00000000-0002-0001-0000-000162286276

Eine wie auch immer gestaltete Erbschaftssteuer wird das vermutlich nicht ändern. Damit keine Missverständnisse entstehen, das Fallenlassen abertausender Menschen, wie es in GB und den USA gang und gäbe ist, will ich nicht als Vorbild verstanden haben. Mein Eindruck ist lediglich, dass soziokulturelle Probleme nicht durch Geld- oder Steuerpolitik gelöst oder gemindert werden.

“Mein Eindruck ist lediglich, dass soziokulturelle Probleme nicht durch Geld- oder Steuerpolitik gelöst oder gemindert werden.”

Alternativvorschläge, wie diese Disparitäten gelöst werden könnten fern der Geldpolitik (ergo des Geldes)?

Nein, zumindest kann ich keine Patentrezepte anbieten. Ich glaube auch nicht, dass es solche gibt.

Eigenverantwortlichkeit, Leistungsbereitschaft, Pragmatismus, sich selber fördern und fordern, klare Absprachen, soziales Engagement halte ich für positive Konzepte.

Die Erwartungshaltung, dass der Staat oder eine andere Authorität alles regeln müsse und auf diese Weise für Glück und Unglück seiner Bürger verantwortlich wäre, halte ich zum Beispiel für ein wenig förderliches Konzept.

Aber die Mentalitäten sind unterschiedlich… anscheinend wünschen sich die Franzosen einen starken Zentralstaat. Und in Berlin und im Ruhrgebiet scheint man auch überwiegend der Meinung zu sein, der Staat soll es richten. In den USA sieht man solche Dinge völlig anders. Dort spielt caritatives Engagement eine viel größere Rolle.

Früher waren die Gewerkschaften in Deutschland dafür zuständig, dass die arbeitende Bevölkerung eine anständige Entlohnung erhält. Heute soll (frei nach Stöcker) ein zentralbankfinanziertes Bürgergeld und eine hohe Erbschaftssteuer dafür sorgen, dass jeder ein menschenwürdiges Leben führen kann? Wo sind die Gewerkschaften eigentlich geblieben?

Wie gesagt, ich glaube nicht das Patentrezepte funktionieren. Die Verteilung der Resourcen wird jedes Land, aber auch in viel kleineren Einheiten, immer wieder neu verhandelt werden müssen.

Der Austeritätsbeitrag von Bernau bei faz.net geht m. A. n. am Problem vorbei:

Es SOLLTE immer eine Art von Austerität geben (Begriff hier nicht technisch verstanden):

So sollte es z. B. Insolvenzen geben dürfen, um damit die Wirtschaft zu quasi ORGANISCHEN Anpassungen zu zwingen. Der kontinuierlich hohe Aufbau von unproduktiver Privat- und Staatsverschuldung durch die Notenbanken (zu laxe Geldpolitik) und die Fiskalpolitik (Finanzierung von Konsum) muss soweit wie möglich verhindert werden. So verstandene Austerität ist nicht bequem, kann aber Verwerfungen mit desaströsen Folgen verhindern.

Wo mehr oder weniger ungebremste Verschuldung stattfindet, u. U. aufgrund von extrem niedrigen, nicht marktkonformen Zinsen wir in Griechenland nach Eintritt in die Eurozone, ist die Lage anders. Ein Budgetdefizit von 13% ist nicht hinnehmbar und muss mit der Brechstange (von der Troika ERZWUNGENE Austeritätspolitik) wie geschehen abgebaut werden mit parallel verlaufenden Strukturreformen. Außerdem hätte das Land weitgehend entschuldet werden müssen. Alles andere ist kontraproduktiv.

Im Sonderfall Griechenland muss das Land die Eurozone verlassen dürfen, um Dauertransferzahlungen zu vermeiden. Dem Land sollte gestattet werden, durch dauerhafte Abwertung einer eigenen Währung zu verarmen.

Kurzum:

Es kommt darauf an, einen Zustand zu verhindern, der harte Austeritätsmaßnahmen erforderlich macht.

Für die Eurozone: Wo der Wille besteht, zu restrukturieren – der Wille und nicht wertlose, nicht durchsetzbare Bekundungen – kann geholfen werden, allerdings mit zwar noch erträglichem, aber dennoch sehr schmerzaftem Umorientierungszwang.

Freiwillig geht in der Eurozone offensichtlich nichts und da Zwang nicht denkbar ist wie in den Fällen Frankreich und Italien, bleibt nur das Scheitern.

„So sollte es z. B. Insolvenzen geben dürfen, um damit die Wirtschaft zu quasi ORGANISCHEN Anpassungen zu zwingen.“

Insolvenzen gab es vor, während und nach der Finanzkrise und hat NICHTS mit Austerität zu tun. Selbstverständlich muss es IMMER einen Selektionsmechanismus geben. Austeritätspolitik vernichtet hingegen auch gesunde Unternehmen, da sie ein prozyklisches Instrument ist: Dümmer geht’s nimmer.

„Dem Land sollte gestattet werden, durch dauerhafte Abwertung einer eigenen Währung zu verarmen.“

Richtig ist, dass Griechenland niemals in den Euro hätte aufgenommen werden dürfen. GR verarmt gerade deshalb, weil es NICHT abwerten kann. Insofern müsste es richtigerweise heißen:

Dem Land sollte gestattet werden, durch dauerhafte Abwertung einer eigenen Währung NICHT zu verarmen.

„Es kommt darauf an, einen Zustand zu verhindern, der harte Austeritätsmaßnahmen erforderlich macht.“

Ja, darauf kommt es an. Leider haben Banken, Rating-Agenturen und Finanzaufsicht gepennt, obwohl hohe persistente Leistungsbilanzdefizite IMMER zu Bankenkrisen führen. Wenn das Kind im Brunnen liegt, dann sollte man nicht auch noch die Rettungsleine hinterherwerfen.

Hier der direkte Link zu Wyplosz aus dem Jahre 2012 (sic!) : The coming revolt against austerity: https://voxeu.org/article/coming-revolt-against-austerity

LG Michael Stöcker

@ Michael Stöcker

“Austeritätspolitik vernichtet hingegen auch gesunde Unternehmen, da sie ein prozyklisches Instrument ist: Dümmer geht’s nimmer.”

Sind gesunde Unternehmen nur dann zu vernichten, wenn ihr Untergang als ein bißchen schöpferische Zerstörung verstanden werden muss, wie z.B. die dt. Autoindustrie oder die Eneregiewirtschaft?

Diese Frage ist keineswegs polemisch, denn die liebe kleine Greta ist über ihre Familie mit dem CO2 Ablaßhandel verstrickt und es dreht sich keinesweg ums Klima, wenn Weltuntergang gepredigt wird….money, money, money

https://www.eike-klima-energie.eu/2019/01/01/ein-superstar-und-jeanne-darc-der-klimakonferenz-sprach-doch-der-saal-war-fast-leer/

(Ich möchte jetzt nicht wegen Quellangaben angegangen werden, niemand interessiert sich für Greta und unsere Medien transportieren Panik. That´s it.)

Meinen Sie EIKE: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Europ%C3%A4isches_Institut_f%C3%BCr_Klima_und_Energie oder den noch trüberen Rest?

LG Michael Stöcker

@ Michael Stöcker

>Insolvenzen gab es vor, während und nach der Finanzkrise und hat NICHTS mit Austerität zu tun. Insolvenzen gab es vor, während und nach der Finanzkrise und hat NICHTS mit Austerität zu tun. Selbstverständlich muss es IMMER einen Selektionsmechanismus geben.>

Das ist schlichtweg falsch – Insolvenzen haben etwas mit Austerität zu tun:

Es ist die VERHINDERUNG von Insolvenzen in GROSSEM Stil durch Geld- und Fiskalpolitik – also die Verhinderung dessen, was ein wirtschaftlich gut begründeter Selektionsmechanismus ist, die zu Zuständen der Überschuldung führt, derart, dass es letztlich zu Austerität kommen MUSS – auf welche Weise sich diese Entzugserscheinungen auch immer ausdrücken.

Und dann trifft es auch an sich gesunde Unternehmen, die sonst vermutlich nicht insolvent geworden wären.

Wer ausblendet, warum es zu Zuständen kommt, die Austerität erforderlich machen, denkt selektiv – und damit letztlich defizitär.

Und er denkt falsch, weil er versucht, Austerität zu vermeiden, wenn sie nicht mehr zu vermeiden ist.

>GR verarmt gerade deshalb, weil es NICHT abwerten kann. Insofern müsste es richtigerweise heißen:

Dem Land sollte gestattet werden, durch dauerhafte Abwertung einer eigenen Währung NICHT zu verarmen.>

Auch das ist falsch.

Griechenland verarmt, weil es auch nach einigen strukturellen Reformen a) keine Wohlstand generierende Volkswirtschaft ist: weder Bodenschätze, noch besonders attraktives Human Kapital, noch – abgesehen von verfallenden Kulturdenkmälern – Urlaubsattraktionen und b) weil es ein Land mit exorbitant hohem nominalen Schuldenüberhang ist, was Investitionsunsicherheit bedeutet.

Aufgrund der Basisbeschaffenheit würde es auch mit eigener Währung verarmen. Der Vorteil wäre, dass dies bei Austritt in eigener Verantwortung der Fall sein würde.

>Leider haben Banken, Rating-Agenturen und Finanzaufsicht gepennt, obwohl hohe persistente Leistungsbilanzdefizite IMMER zu Bankenkrisen führen.>

Wenn man richtig regulieren würde – etwa durch ein Trennnbankensystem – müssten auch Banken insolvent werden können.

Wenn man das anscheinend Undenkbar als normal ansieht, hat man zwar keine schöne, heile Welt, ist aber viel weiter von Austeritätserfordernissen entfernt.

@ Michael Stöcker

Mein Zitat:

“Ich möchte jetzt nicht wegen Quellangaben angegangen werden”

Ihr Zitat:

Meinen Sie EIKE… oder den noch trüberen Rest?

Aber genau null Antwortversuch zur Frage:

Sind gesunde Unternehmen nur dann zu vernichten, wenn ihr Untergang als ein bißchen schöpferische Zerstörung verstanden werden muss, wie z.B. die dt. Autoindustrie oder die Eneregiewirtschaft?

Sie überraschen immer weniger.

Wenn wir keine AfD hätten, müsste man sie erfinden, des Pluralismus wegen. Leider war der Gründer Lucke ökonomisch auf einem sehr Stöcker ähnlichen Holzweg unterwegs, seine Interviews zur Ökonomie waren reiner mainstream.

@Herr Tischer

“Es ist die VERHINDERUNG von Insolvenzen in GROSSEM Stil durch Geld- und Fiskalpolitik – also die Verhinderung dessen, was ein wirtschaftlich gut begründeter Selektionsmechanismus ist, die zu Zuständen der Überschuldung führt, derart, dass es letztlich zu Austerität kommen MUSS”

Sehr richtig – in der Finanzkrise hätten es viel mehr Unternehmen, insbesondere Banken und Versicherungen, verdient gehabt, insolvent zu gehen. Die wurden aber stattdessen vom Staat gerettet und mit billigen Krediten vollgepumpt, und die Konsequenzen daraus sind Zombifizierung, perverse Anreize für weiteres hochriskantes Wirtschaften mit Aussicht auf das nächste Rettungspaket, und eben Austerität.

@Dietmar Tischler

“Es ist die VERHINDERUNG von Insolvenzen in GROSSEM Stil durch Geld- und Fiskalpolitik – also die Verhinderung dessen, was ein wirtschaftlich gut begründeter Selektionsmechanismus ist, die zu Zuständen der Überschuldung führt, derart, dass es letztlich zu Austerität kommen MUSS – auf welche Weise sich diese Entzugserscheinungen auch immer ausdrücken.”

Sie spielen vermutlich auf Schumpeters schöpferische Zerstörung an. Er hatte dabei jedoch Innovationen als Auslöser im Hinterkopf, keine externen Schocks durch Austeritätspolitik. Insolvenzen sind nötig, aktiv herbeigeführte jedoch nicht (für Geschäftsführer ist die aktive Herbeiführung sogar strafbar).

“Griechenland verarmt, weil es auch nach einigen strukturellen Reformen a) keine Wohlstand generierende Volkswirtschaft ist: weder Bodenschätze, noch besonders attraktives Human Kapital, noch – abgesehen von verfallenden Kulturdenkmälern – Urlaubsattraktionen und b) weil es ein Land mit exorbitant hohem nominalen Schuldenüberhang ist, was Investitionsunsicherheit bedeutet.”

Bodenschätze sind historisch gesehen wohl eher ein Garant für geringen Wohlstand, und so schlecht ist das Bildungssystem nicht, dass die Griechen kein Humankapital hätten. Verarmung findet wohl eher statt, wenn das Land aufgrund mangelnder Kaufkraft in eine Negativspirale kommt und Produktionskapazitäten wegen der geringen Nachfrage abgebaut werden.

Nutznießer sind die Chinesen, welche sich aktuell in Griechenland etablieren und eine einfache Möglichkeit gefunden haben, ihre Ideologie auch in der EU zu verbreiten. Wir müssen aufpassen, dass sie sich nicht zur faktischen Vetomacht entwickeln.

“Wenn man richtig regulieren würde – etwa durch ein Trennnbankensystem – müssten auch Banken insolvent werden können.”

Zustimmung in dem Punkt

@ Christian

Ich denke nicht nur an Schumpeter und die schöpferische Zerstörung.

Ich denke z. B. auch daran, dass kein großes Automobilwerk in Deutschland schließen darf, auch wenn es 20% Überkapazität der Produktion gibt.

Das oder die unrentabelsten müssen schließen, d. h. im Extremfall Insolvenz anmelden, weil sie keine Gewinne erwirtschaften und daher Ressourcen volkswirtschaftlich unproduktiv einsetzen.

Das wird durch Subventionen vermieden und führt zu Verschuldung, übrigens auch von Unternehmen.

Wird das lang genug betrieben, landet man bei Überschuldung.

DANN – als FOLGE dieser Vermeidungsstrategie – kommt es zu korrigierender Austerität, weil der Weg eben nicht ewig beschritten werden kann.

Nochmal, um nicht missverstanden zu werden:

Insolvenzen sind kein Zuckerschlecken, sondern verursachen Ungemach und auch Leid.

In einer sich WANDELNDEN Wirtschaft ist das unvermeidlich.

Hier geht es lediglich darum, wie AUSTERITÄT vermieden werden kann.

Sie kann vermieden werden, aber auch das hat einen Preis, u. a. Insolvenzen und die stetige Bereitschaft, sich u. U. umorientieren zu müssen.

Schon wieder eine TARGET2-Diskussion?

Dazu ist doch mittlerweile alles gesagt: Die Target-Salden sind so lange irrelevant, bis ein Land aus dem Euro austritt und sie dann, laut offizeller Auffassung der EZB, ausgleichen muss. Aber da mit dem Euro ja alles super läuft, wird so ein Euro-Austritt garantiert nie passieren… ;)

@ Richard Ott

“Die Target-Salden sind so lange irrelevant, bis ein Land aus dem Euro austritt….”

Das sieht HWS anders: https://www.cesifo-group.de/DocDL/sd-2018-24-fuest-sinn-target-risiken-2018-12-20.pdf

ad Michael Söcker:

Der IWF hat Griechenland gerettet. So zumindest Ihr gestern verlinkter FAZ-Artikel.

Zum Thema Banken-Run:

Sind die Bunker der NZB voll mit Banknoten, werden die Automaten aufgefüllt in einem solchen Szenario, ist diese Operation neutral, da nach Abheben-Aufheben-Ausgeben-Wieder-Einzahlung die Banknoten eingezogen werden (hat sich die Hysterie gelegt)? Gibt es hierzu Vereinbarungen zwischen EZB/NZB und den Geschäftsbanken (Vermerk der Seriennummern der Banknoten für einmalig einzusetzende Zwecke)?

@Horst:

“..da nach Abheben-Aufheben-Ausgeben-Wieder-Einzahlung die Banknoten eingezogen werden…”

Vielleicht kommt der ein oder andere auch auf die Idee, dass so viel Bar(papier)geld von starkem Wertverlust bedroht sein könnte, insbesondere, wenn viele anfangen und damit einkaufen gehen. Was dann?

w/Target

Im Januar sind die deutschen Target Salden nach Beendigung von QE so stark wie noch nie zurückgegangen. Minus 98 Mrd. auf 868 Mrd Euro. Rückgang war zu erwarten, Ausmaß aber doch überraschend hoch. Deutet aber eben auf den hier mehrfach angeführten Zusammenhang zwischen QE und Target Salden hin. Dies nehmen hoffentlich auch die Target Kritiker zur Kenntnis.