Die Belastung durch Energiekosten ist erheblich

Energie ist erneut das Thema im Podcast am kommenden Sonntag (29. Januar 2023). Zu Gast ist Prof. Dr. Lion Hirth, Professor für Energiepolitik an der Hertie School. Zur Einstimmung ein paar Daten.

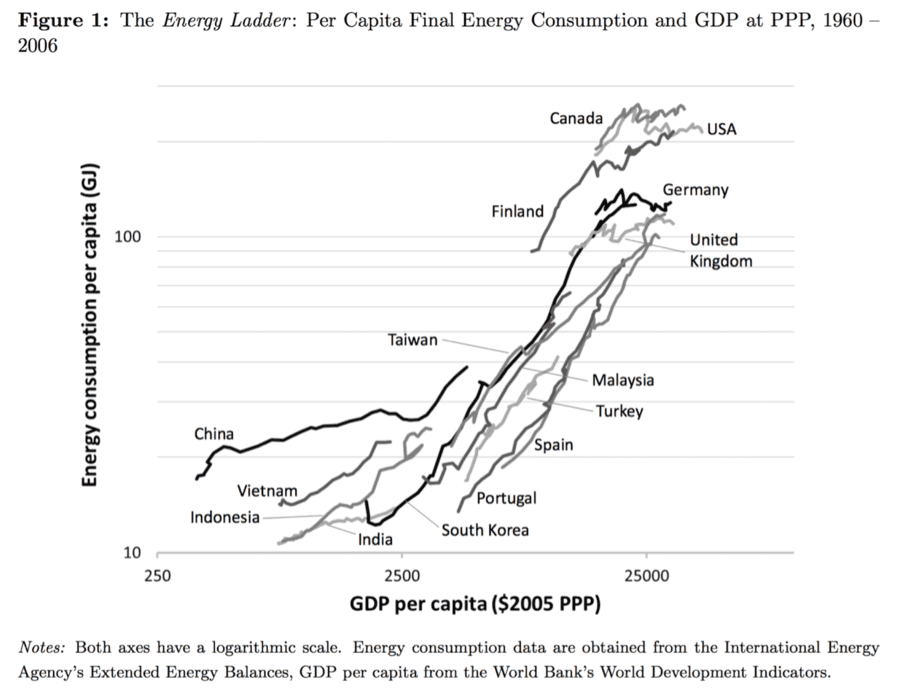

Zunächst erinnern wir uns daran, dass Wohlstand eng mit dem Einsatz von Energie verbunden ist:

Wir sehen aber auch sehr schön, dass es Deutschland in den letzten Jahren gelungen ist, ein höheres BIP/Kopf zu erwirtschaften, ohne den Energieeinsatz zu erhöhen. Wir sind also effizienter geworden. Unabhängig davon liegen wir deutlich unter den USA und Kanada.

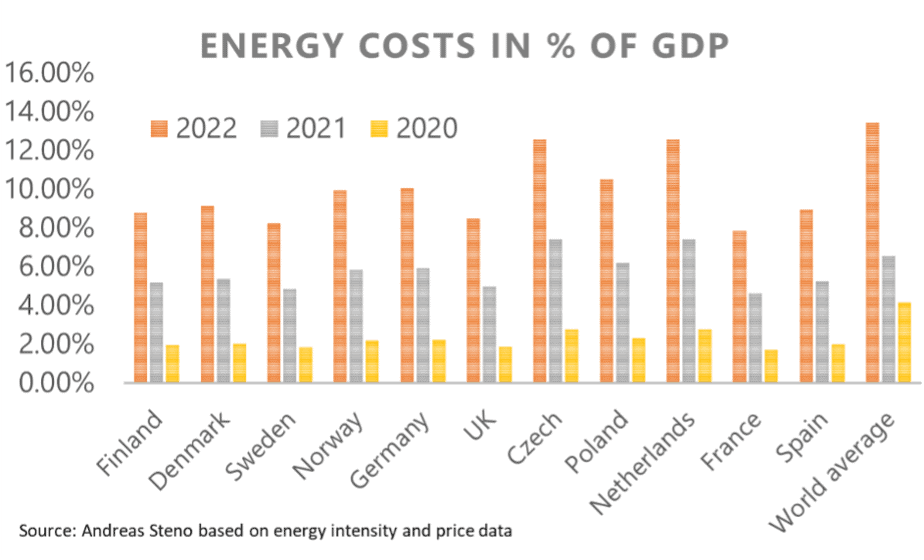

Trotzdem trifft uns der Energiekostenschock deutlich:

- „Energy costs in Europe as a percentage of GDP double signaling a persistent headwind. Energy costs as a % of GDP in 2020, 2021 and 2022 in Europe (and the world average).” – bto: Die Welt als Ganzes ist natürlich auch getroffen, weil die ärmeren Staaten relativ zum BIP mehr für Energie aufwenden müssen.

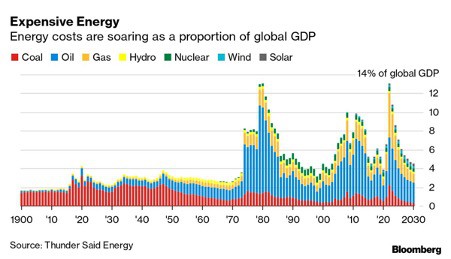

Global sieht es so aus:

Nun sieht man die Lösung in einem raschen Ausbau der Erneuerbaren Energien. Einige Klimaökonomen fordern gar den sofortigen Verzicht auf jegliche Investitionen in erneuerbare Energien:

Im Interview mit dem Blog „Treibhauspost“ äußerte sich Deutschlands bekannteste Energie-Ökonomin Claudia Kemfert über Ihren Traum für das Jahr 2023 so:

„Der fossile Energiekrieg in Europa ist beendet, am besten überall auf der Welt. Die letzte Schlacht ist geschlagen. Gewonnen haben endlich die erneuerbaren Energien. In sie wird weltweit massiv investiert. In fossile Energien oder Infrastrukturen dagegen fließen keine, wirklich gar keine Investitionen mehr. Nicht in oder aus Deutschland, nicht in oder aus Europa, am besten nirgends auf der Welt.“

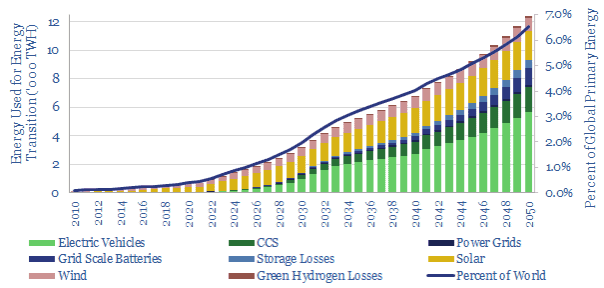

Was gerne vergessen wird: Auch die Energiewende braucht Energie.

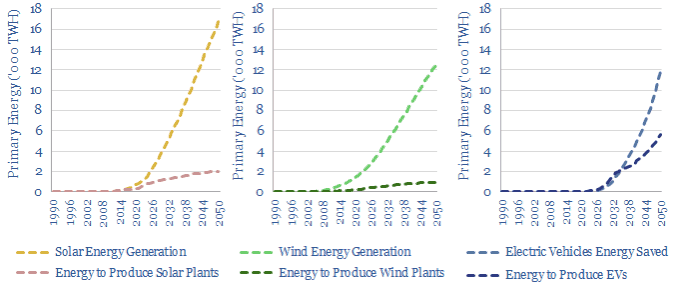

- „Reaching net zero requires building wind, solar, grid infrastructure, energy storage, electric vehicles and capturing CO2. Energy is needed to build all of these things. The total energy costs of energy transition reach 1% of total global primary energy in 2025, 2% in 2030, 4% in 2040 and 6.5% in 2050. In other words, energy transition is materially easier to achieve from a period of energy surplus.“ – bto: Je früher wir also Energie verteuern, desto schwerer wird auch der Umbau der Energieversorgung.

- „We want to achieve an energy transition, by ramping wind and solar to 25% of the world’s total useful energy by 2050 (note here), building a global fleet of over 2bn efficient electric vehicles, constructing power grid and storage infrastructure, and capturing over 6GTpa of CO2 via various forms of CCS. (…) However, building all of these things absorbs energy. There are energy intensive materials in a solar plant. There are energy intensive materials in a wind-turbine. And in electric vehicles. Around two-thirds of the energy costs for expanded power grids is embedded in the aluminium of power cabling. Finally, energy storage consumes energy in the form of round-trip efficiency losses, while CCS consumes energy in regenerating amines.” – bto: Letztlich ist das alles nicht überraschend. Dass es keine Rolle in der Diskussion spielt, ist eher überraschend.

- „These are simply enormous numbers. The 2025 number is equivalent to the total primary energy consumption of a country such as Spain or Australia. While the 2050 number is equivalent to two Saudi Arabias worth of oil production.“ – bto: Das sind wirklich beeindruckende Zahlen.

- „It is clearly going to be easier to build the important assets and infrastructure needed in the energy transition from a position of energy surplus, and it is going to be more difficult (even, inflationary) if the world is suffering from sustained energy shortages. This is why we think restoring the world’s energy surplus is the most important ESG goal of the 2020s.“ – bto: … eine These, der Klimapolitiker entschieden widersprechen.

- „Wind is already in a position of large energy surplus, because wind plants require 50-70% less up-front energy to construct than solar plants (per unit of ultimate generation, e.g., in kWh). The solar chart below is also more finely balanced through the mid-2020s, because solar additions are still accelerating sharply (note here). EV growth is seen accelerating so sharply that building ever more EVs will absorb more energy than they save through the mid-2030s.“ – bto: Immerhin bringen alle drei mehr Energie, als sie kosten.

- „The technology that looks most challenged on this roadmap is green hydrogen. Converting useful, rateable electricity into green hydrogen generates no energy savings. There are simply efficiency losses, due to entropy increases, over-voltages at the anode, storage, transport, fuel cells, etc. (…) <0.1% of the world’s useful energy in 2050 (will be) coming from green hydrogen. But if the number were 10%, then the total energy requirements of the energy transition would literally double.“ – bto: Auch das sind simple Überlegungen. Fragt sich, wieso diese nicht vorgenommen werden.

- „The technology that looks least challenged on this roadmap is natural restoration. Nature based solutions may create a 20GTpa CO2 sink with long-term pricing around $50/ton. But planting trees is not an energy intensive activity. There is even an argument that it generates energy, although consuming this energy has varying CO2 credentials.“ – bto: Auch das leuchtet ein.

- „A key objective for the new energies industry is going to be deploying new technologies that can improve efficiency and lower the energy intensity of energy transition.“ – bto: Das setzt voraus, dass man den Wandel zu neuen Technologien günstig gestaltet, nicht teuer.

Fazit: Wir haben es immer wieder mit einer Situation zu tun, in der Ideologien, Illusionen und Träume den Blick für die Realität vernebeln.

→ steadyhq.com: „‘Wir stecken längst in einem fossilen Energiekrieg‘“, 14. Januar 2023

→ thundersaidenergy.com: „Energy costs of energy transition?“