Zinsen: Trendwende ja oder nein?

Mehr als einmal habe ich mich bei bto mit dem Thema Zinsen beschäftigt. Im Vordergrund standen dabei Thesen, die besagen, dass Zinsen nicht nur wegen der Notenbankpolitik so tief sind und noch lange tief bleiben müssen:

→ Warum sind die Zinsen so tief

→ Säkulare Stagnation als Grund für tiefe Zinsen?

→ Niedrigzinsen aus Mangel an sicheren Anlagen in überschuldeter Welt

→ „Tiefe Zinsen bis der Ketchup spritzt“

Skepsis habe ich allerdings auch geäußert, vor allem davor gewarnt, sich bei der Geldanlage auf ewig tiefe Zinsen einzustellen:

→ Zinsen hoch oder runter – was kommt?

Nun eine interessante Studie, die auf dem Blog der Bank of England erschienen ist und sich mit der historischen Erfahrung mit Zinssteigerungen auseinandersetzt:

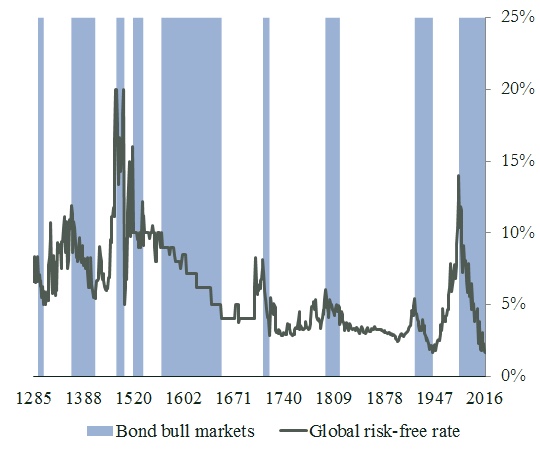

- “Looking back over eight centuries of data, I find that the 2016 bull market was indeed one of the largest ever recorded. History suggests this reversal will be driven by inflation fundamentals, and leave investors worse off than the 1994 ‚bond massacre‘.” – bto: Das kann angesichts der globalen Verschuldung nicht funktionieren. Das wäre der Crash.Chart 1: The Global risk free rate since 1285

Quelle: Bank Underground/Paul Schmelzing

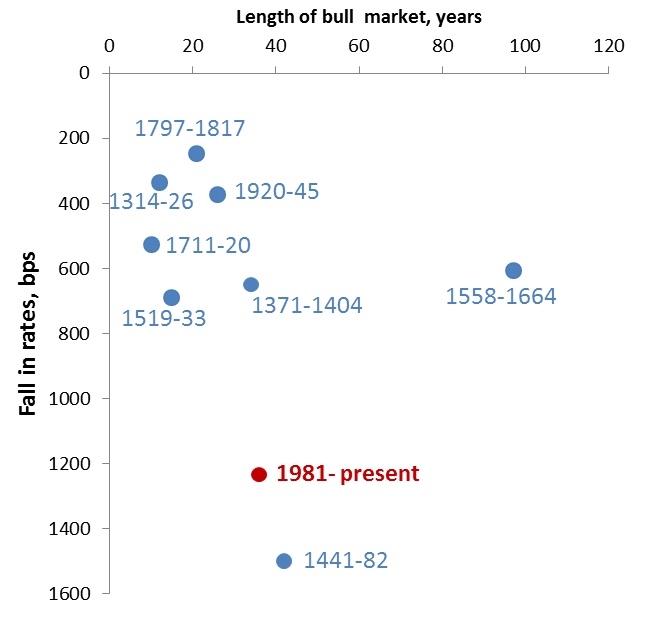

- “(…) judging purely by historical precedent, at 36 years, the current bond bull market had been stretched. As chart 2 shows, over 800 years only two previous episodes – the rally at the height of Venetian commercial dominance in the 15th century, and the century following the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559 – recorded longer continued risk-free rate compressions.” – bto: Ich finde so lange Zeitreihen immer wieder beeindruckend.

Chart 2: Length and size of bull markets since 1285

Quelle: Bank Underground/Paul Schmelzing

- “(…) on our count the United States (the current issuer of the global risk-free asset) experienced 12 modern ‚bond shock‘ years, during which selloff dynamics cost long-term sovereign bond creditors more than 15% in real price terms.” – bto: Bei über 15 Prozent könnten wir noch froh sein. Käme es wirklich zu einem Sell-off, wäre das weitaus schlimmer.

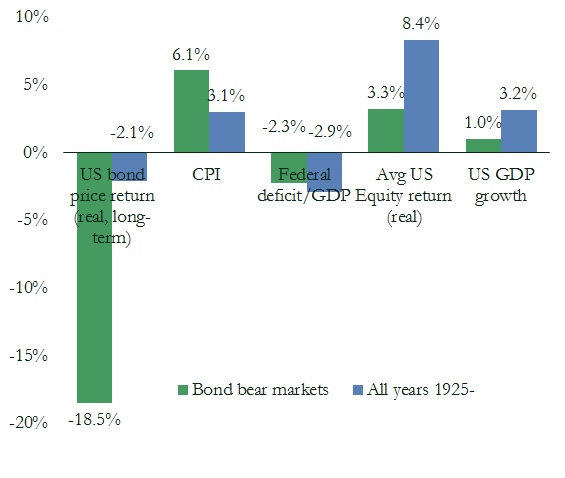

- “Aggregating these bear markets (chart 3), we find that, at 6.1% CPI year-on-year on average, ‚bond shock years‘ record inflation levels almost double the long-term trend, at 3.1%. Global growth equally is below average, though not in recession territory.”

Quelle: Bank Underground/Paul Schmelzing

Danach zeigt Schmelzing einzelne historische Perioden mit deutlichen Einbrüchen. Interessanterweise ist es jedoch so, dass es auch zu deutlichen Einbrüchen gekommen ist, OHNE dass die Inflation wesentlich zugenommen hat, so in den 1990er-Jahren, wo die Inflationserwartungen bei 3.4 Prozent den Höhepunkt erreichten. Ursache war vielmehr “the dramatic increase in leveraged bond positions by both US hedge funds and mundane money managers set in motion self-reinforcing liquidations once uncertainty over emerging markets including Turkey, Venezuela, Mexico, and Malaysia put pressure on speculative positions“. – bto: Es war also ein klassischer Margin Call.

In Japan kam es 2003 zu deutlichen Verlusten am Bondmarkt. Auch hier nicht unbedingt wegen Inflation. Stattdessen auch mehr eine Marktreaktion: “(…) markets underwent a notable rollercoaster of the term structure against the backdrop of ‚tapering fears‘ over the BoJ’s bond buying program, the Iraq War, and domestic tax hikes. (…) calibrated risk management structures, known as ‚Value-at-Risk‘ models, required banks to shed JGB assets once their price started plummeting. Since most banks followed similar quantitative signals, and exerted a traditionally strong home bias in their fixed income portfolios, a concerted dumping of government bonds ensued.” – bto: Man kann also sagen, es hat eher mit der einseitigen Positionierung der Marktteilnehmer zu tun, was wir auch heute haben.

Gerade die Beziehung zur Gesundheit der Banken scheint nicht richtig gesehen zu werden: “(…) the IMF has warned that VAR risks have risen ‚significantly‘ in Japanese financial institutions after the financial crisis, given a continued build-up of JGB concentration in balance sheets. In Europe, the trend is equally one-directional: Italian monetary financial institutions, for instance, hold 18% of their assets in domestic government loans and securities, up from 12% in 2008. In most geographies, these bonds, despite efforts to the contrary, remain mainly held in ‚available-for-sale‘ portfolio buckets, where they have to be marked-to-market.” – bto: Wow! Wir haben also einen perfekten Margin Call und vor allem wirken die Zinsen nicht so positiv auf Banken, wie man so gerne denkt.

Fazit Schmelzing: “On balance, then, more than to a 1994-style meltdown, fixed income assets seem about to be confronted with dynamics similar to the second half of the 1960s, coupled with complications of a 2003-style curve steepening. By historical standards, this implies sustained double-digit losses on bond holdings, subpar growth in developed markets, and balance sheet risks for banking systems with a large home bias.” – bto: Das wäre der Kollaps. Schwer denkbar, dass es so kommt. Lieber werden die Notenbanken “all-in” gehen und nochmals Zeit kaufen. Mehr können sie allerdings nicht.