Wo bleibt die Inflation? (I)

Eine der Kernfragen dieses Aufschwungs bleibt unbeantwortet: Wo bleibt die (Lohn-)Inflation angesichts tiefer Arbeitslosigkeit und aggressiver Geldpolitik? (USA: zumindest, wenn man die offiziellen Zahlen nimmt.) Eigentlich müssten wir doch schon längst höhere Inflationsraten haben und damit die erhoffte Entwertung der Schulden. Eine mögliche Erklärung könnte in den geringen Produktivitätszuwächsen liegen.

Das diskutiert Ben Hunt mit Blick auf die Politik der Notenbanken, die nun beginnen die Geldflut einzudämmen, so seine Meinung:

- “The question, then, isn’t whether the barge of monetary policy has turned around and embarked on a tightening course — it has — the question is how fast that barge is going to move AND whether or not the market pays more attention to the actual barge movements than what the barge captain says. I promise you that the barge captains of both the Fed and the ECB believe they can tighten and taper without killing the market so long as they jawbone this constantly. (…) It WILL absolutely work unless and until we get undeniably “hot” inflation numbers – particularly wage inflation numbers – from the real world.” – bto: weil, dann müssten die Notenbanken schneller die Zinsen erhöhen und die Märkte würden in Erwartung, dass dies funktioniert, den Zinsanstieg vorwegnehmen und damit crashen – der ultimative Margin Call.

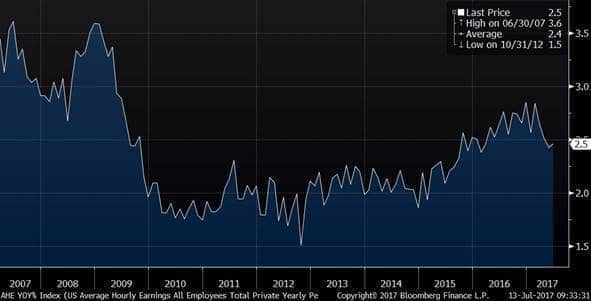

- “How can we have wage inflation running at a fairly puny 2.5 % (Chart 1 below) when the unemployment rate is a crazy low 4.3 % (Chart 2 below) and other indicators, like the NFIB’s survey of ‚Small Business Job Openings Hard to Fill‘ (Chart 3 below) are similarly screaming for higher wages?” – bto: Das ist die Frage, die sich Draghi & Co. schon lange stellen. Es dürfte auch daran liegen, dass die Beschäftigungsquote deutlich gesunken ist.

Chart 1: US Average Hourly Earnings, annual % change

Chart 2: US Unemployment Rate

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P. as of 7/13/17. For illustrative purposes only.

Chart 3: NFIB Small Business Job Openings Hard to Fill

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P. as of 7/13/17. For illustrative purposes only.

- “The answer, I think, can be found in Chart 4 below: vanishing labor productivity. (…) You can have productivity growth for good reasons like in the 1980s and 1990s and early 2000s (more stuff made per hour worked as companies invested in things like the personal computer or the Internet) or bad reasons like in 2009 and 2010 (massive layoffs, so making a bit less stuff but over waaay fewer hours worked).” – bto: was eine natürliche Reaktion der Unternehmen ist.

- “Productivity growth for the right reasons is just about the most important economic goal that policy makers have, because it’s how you get your economy growing in a sustainable, non-inflationary way, and for the past seven years we’ve had none of it.” – bto: Deshalb sprechen wir auch von säkularer Stagnation.

- “By the way, if new technologies were really responsible for keeping wage inflation down (something I hear all the time), we would have seen that through increasing labor productivity. We haven’t.” – bto: Das ist eine der Kernaussagen. Die neuen Technologien schlagen sich nicht wie gewünscht in der Wirtschaft nieder. Vielleicht kommt das noch, hatten wir hier auch diskutiert. Noch sieht man es nicht:

Chart 4: US Labor Productivity Growth (2-year moving average)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics as of 7/13/17. For illustrative purposes only.

- “How is it possible — with the most accommodative monetary policy in the history of the world, with the easiest money to borrow that corporations have ever experienced, with all the amazing technological advancements that we read about day in and day out – that companies have not invested more in plant and equipment and technology to improve their labor productivity, to make more with the people they’ve got?” – bto: Ich denke, es liegt einfach daran, dass die Unternehmen es nicht mussten. Sie konnten so gutes Geld verdienen und zudem über Financial Engineering weitaus mehr erreichen.

- “The reason companies aren’t investing more aggressively in plant and equipment and technology is BECAUSE we have the most accommodative monetary policy in the history of the world, with the easiest money to borrow that corporations have ever seen. Why in the world would management take the risk – and it’s definitely a risk – of investing for real growth when they are so awash in easy money that they can beat their earnings guidance with a risk-free stock buyback? Why in the world would management take the risk – and it’s definitely a risk – of investing for GAAP earnings when they are so awash in easy money that they can hit their pro forma narrative guidance by simply buying profitless revenue? Why in the world would companies take any risk at all when the Fed has eliminated any and all negative consequences for playing it safe?” – bto: Und warum sollte man investieren, wenn die Wettbewerber auch ohne Investitionen mit billigem Geld im Markt gehalten werden?

- “As the Fed slowly raises rates (…) it will force companies to play it less safe. It will force companies to take on more risk. It will force companies to invest more in plant and equipment and technology. It will force companies to pay up for the skilled workers they need. You want wage inflation? You want productivity growth? Then raise rates!” – bto: Theoretisch bin ich dabei, allerdings haben wir das Problem, dass wir zu viele Schulden haben, was dann zu (mindestens) einer Rezession führt.

- “In exactly the same way that QE was deflationary in practice when it was inflationary in theory, so will the end of QE be inflationary in practice when it is deflationary in theory.” – bto: Das ist eine sehr interessante Aussage.

- In the Bizarro-world that central bankers have created over the past eight years, raising rates isn’t going to have the same inflation-dampening effect that it’s had in past tightening cycles, at least not until you get to much higher rates than you have today. It’s going to accelerate inflation by forcing risk-taking in the real world (…).” – bto: Ich denke schon, dass das dann eine Schuldenkrise auslöst.

- “(…) as the tide of QE goes out, the tide of inflation comes in. And the more that the QE tide recedes, the more inflation comes in.” – bto: Das führt dann aber wieder zu Rezession und noch mehr (deflationärem) QE im Kampf, den Schuldenturm irgendwie zu stabilisieren.

→ Epsilon Theory: “Gradually and Then Suddenly”, 18. Juli 2017