Welche Reformen der Kapitalismus braucht

Michael Sandbu von der FINANCIAL TIMES (FT) stellt dort sein neues Buch mit dem Titel “The Economics of Belonging: A Radical Plan to Win Back the Left Behind and Achieve Prosperity for All” vor. Auf jeden Fall kann man feststellen, dass er den Zeitgeist gut trifft und nicht wenige seiner Kritikpunkte sind berechtigt. Wie immer muss die Frage aufgeworfen werden, ob die Ursachen vollständig erfasst sind und daraus abgeleitet, die Medizin. Die Kernaussagen:

- “As an economic commentator for the FT, I have spent years trying to understand the causes of economic polarisation in the western world, its effects and what policies might reverse it. Like many others, I have worried that when our societies divide economically, they also fall apart culturally and politically.” – bto: Das ist in Deutschland bekanntlich weitaus weniger das Thema als in den angelsächsischen Ländern. Bei uns wird es umso lauter diskutiert.

- “(…) will Covid-19 remake society? (…) It is tempting to think we could be at a 1945-style moment, a year remembered as ushering in a new era. As Branko Milanovic, the economist known for his work on global inequality, writes, it is ‘utterly wrong to believe that history does not matter and that the social and political changes wrought by the pandemic can be ignored’. The political forces it has set in motion, he suggests, ‘will fundamentally affect how economies behave in the future’.” – bto: Milanovic hat das Elephant-Chart erstellt, was zeigt, wie der Wohlstand weltweit gestiegen ist, nur eben nicht in der Mittelschicht im Westen. Er hat auch illustriert, dass jene mit Vermögen nicht selten die sind, die auch viel verdienen, weil sie gut ausgebildet sind.

- “Donald Trump, the architects of Brexit and populist movements across Europe all advanced by appealing to groups that felt forgotten by elites and saw the economic system as rigged against them. They have, in effect, been promising to restore the post-1945 era and bring about the sort of moral reordering we glimpsed in the lockdown.” – bto: Nicht wenige Politiker wollen die Krise aber auch nutzen, um ihre ideologischen Vorstellungen durchzusetzen.

- “There is a ‘rhetoric of how the golden days were better’, says political scientist Catherine De Vries. (…) By happy accident as well as by policy design, the postwar industrial economy of the west was particularly well-suited for most people to share in economic growth. The three decades the French call les trente glorieuses produced a remarkable convergence in income and wealth levels between rich and poor, between workers of different educational levels, between countryside and city.” – bto: Dieses Gleichgewicht wurde aber auch durch die bildungsmäßige Polarisierung gestört. Wenn Bildungsstandards sinken und die Zuwanderung überwiegend in den bildungsfernen Bereichen stattfindet, dann hat man eine Störung des Gleichgewichts.

- “(…) having grown up in Norway in the 1970s and 1980s — a time and place that arguably came as close as any modern society to the ideal of an economy with a place for everyone. Few have ever had lower economic inequality or a shorter social distance between top and bottom, and managed to combine it with high productivity and strong growth.” – bto: Ölreichtum hilft allerdings.

- “When I was living in New York in the 2000s, one mundane activity struck me as embodying the economic difference between the US and Norway: having your car cleaned. On entering a New York car wash, you would be set upon by a group of workers — often immigrants — who proceeded to clean your car by hand. In my childhood in Norway, your choice was between an automated car wash or doing the job yourself.” – bto: weil in den USA gearbeitet werden muss, um das Leben zu finanzieren, vor allem auch als Migrant. Damit zieht ein Land auch jene an, die aus eigener Arbeit ihr Glück versuchen wollen.

- “It was the difference between an economic model employing low-productivity, low-wage labour and one where wage equality made it commercially necessary to automate to make labour more productive. It was, too, the difference between the precariat and what I think of as an economy of belonging.” – bto: Wir haben vor Hartz IV genau das gehabt. Arbeitslosigkeit wurde finanziert und für einfache Tätigkeiten war niemand zu finden. Ist das wirklich “gerecht”, dass jene, die willig und fähig sind zu arbeiten, damit die anderen finanzieren?

- “We moved from an economy of belonging to an economy divided between the successful and the left behind. (Et in Arcadia Ego: the manual car wash has had a renaissance in Norway too, courtesy of underpaid immigrants.)” – bto: Leser des Blogs kennen meine Frage: Geht es den Migranten wirklich schlecht, verglichen mit dem Leben im Herkunftsland? Muss man die Gehälter so hochsetzen, dass die Migranten nicht mehr arbeiten können, weil ihnen die Qualifikation fehlt? Oder haben Migranten den Anspruch, von der aufnehmenden Gesellschaft dauerhaft finanziert zu werden? Wie soll Integration gelingen, wenn Eingewanderte nicht am Arbeitsleben teilnehmen?

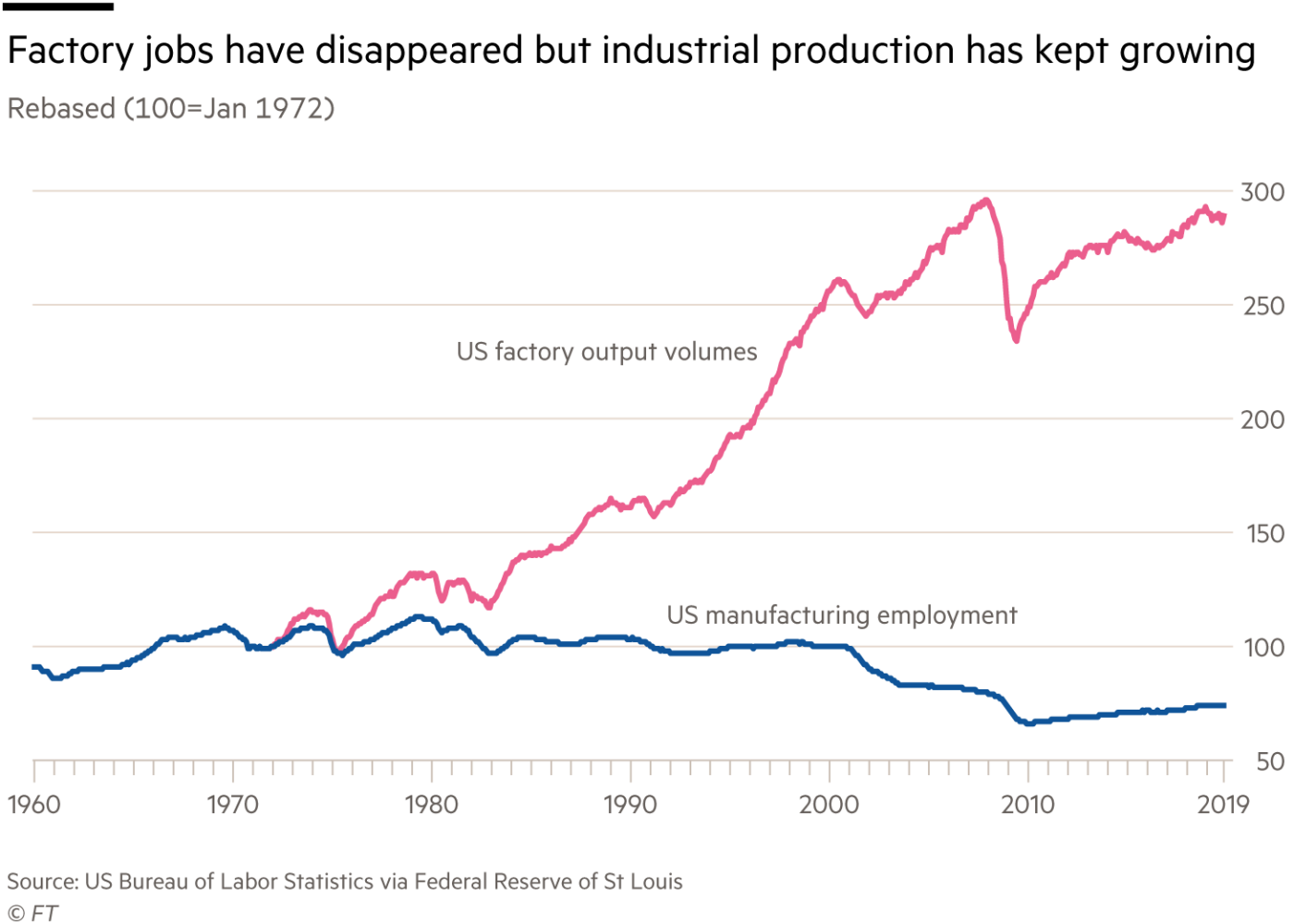

- “It is a widespread misunderstanding that the shift from industrial to knowledge-intensive economy involved manufacturing vanishing, or being whisked off to China and other low-cost countries. In fact, most rich economies produce about as much stuff today as they ever have.” – bto: weil die Automatisierung funktioniert hat.

Quelle: FT

- “Growing productivity through automation and better know-how meant ever fewer hands were needed on assembly lines. New jobs were created in services but many of these were less productive, less well paid and less secure than the ones they replaced, as well as geographically distant from them. (This also meant growth rates slowed down, since manufacturing made up a shrinking share of employment even as its own productivity kept growing.)” – bto: Das ist eine sicherlich interessante weitere Erklärung für den Rückgang der Produktivitätsfortschritte in der Welt. Die Verschiebung von Produktion zu Service.

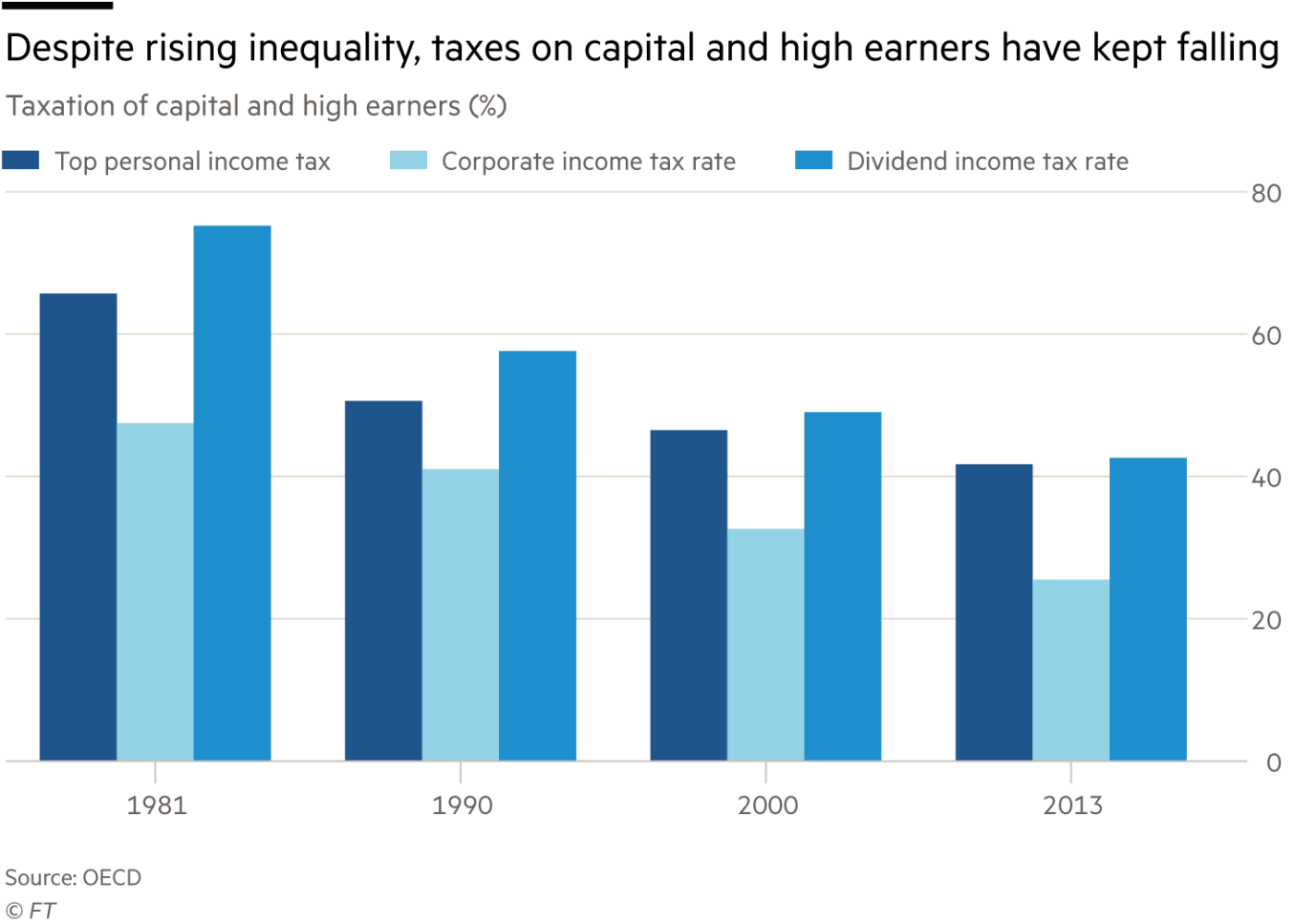

- “These changes are not, on the whole, the fault of globalisation, that scapegoat of the populist insurgency, but of technology-driven changes combined with policies that have reinforced the underlying forces of divergence. For example, western countries shifted tax burdens away from capital and high-wage incomes even as income and wealth inequality rose. Unions, which played a part in reducing income inequality, have declined almost everywhere.”

Quelle: FT

- “In many countries, median wages fell behind labour productivity after tracking it closely for decades. Income inequality and wealth inequality both started rising from around 1980. New jobs were not all created equal: manual and routine work lost out to knowledge work, as pay and job security increasingly depended on workers’ educational background and on where they lived.” – bto: a) Was ist falsch daran, wenn es sich mehr nach der Bildung richtet, vor allem wenn wir Zuwanderung haben? b) Dass die Vermögen zugenommen haben, liegt ja vor allem an der gestiegenen Verschuldung und dem Leverage-Effekt.

- “(…) I frequently argued that a Roosevelt-style ‘centrist radicalism’ (…) What would this look like today? It would not give up on globalisation. Instead, to close the economic fractures we have allowed to open in the past 40 years, I think such a programme would need to achieve five goals.” – bto: Und ich denke, es lohnt sich, genau diese fünf Punkte zu diskutieren.

- “First, it would jettison business models based on using low-productivity (and therefore low-paid) labour, and harness automation rather than resisting it. That means allowing low-productivity jobs to be competed out of existence by higher-productivity ones. Scandinavia has long shown how this can be done: high wages at the bottom of the distribution encourage employers to automate and boost productivity, while high skill levels and active labour-market policies help workers change jobs frequently and adapt to technological developments.” – bto: Das gefällt mir natürlich, weil wir aufgrund der demografischen Entwicklung genau dies brauchen. Allerdings halte ich es dann zwingend für notwendig, die Zuwanderung zu steuern. Hält diese in der heutigen Form an, wächst sonst eine noch größere Gruppe von Transferempfängern heran, die gar keine Chance haben, am Arbeitsmarkt teilzunehmen. Zu glauben, diese ließen sich so einfach qualifizieren, ist schlicht naiv.

- “Second, the programme would aim to shift more labour-market risk from employees to employers and the welfare system. That means lower tolerance for erratic earnings that make it harder for people to plan, retrain and seek new and better work. And it means avoiding aggressive means-testing of benefits, which, when combined with tax, leaves many lower-middle earners facing effective marginal income-tax rates of around 80 per cent or more.” – bto: Den zweiten Punkt verstehe ich. Gerade in Deutschland ist die Abgabenlast in diesem Bereich sehr problematisch. Andererseits wissen wir, dass es wichtig ist, einen Anreiz zu geben, schnell wieder einen Job zu finden.

- “Together, these two principles point in the direction of higher minimum wages, a universal basic income (or its less budget-heavy equivalent, a negative income tax), generous government funding for education and labour-market mobility, and strict enforcement of labour standards.” – bto: Es ist ein Programm, das Teile der Bevölkerung auf Dauer zu Transferempfängern macht. Es gibt aber der Mittelschicht keine große Sicherheit, nur mehr Belastung, denn am Ende zahlt immer die Masse.

- “Third, we can reform taxes to counteract economic divergence instead of intensifying it. That means lowering taxes that penalise hiring. To pay for this, as well as for a negative income tax and policies supporting a well-working labour market, other taxes have to go up. The best candidates are a net wealth tax — which, unlike other capital taxes, favours those who put their capital to the most productive use — and removing the gaping loopholes in multinational taxation, as well as increasing tax revenue from carbon emissions, in line with the climate challenge. A particularly promising proposal is the “carbon tax and dividend”, where revenue from higher emissions taxes would be paid out as a universal basic income.” – bto: Während ich den ersten Punkt der Entlastung von Arbeit teile, sehe ich die Themen BGE und Umverteilung über CO2-Steuern kritisch. Wiederum würden wir einen Transfer vornehmen, der vor allem bei bildungsfernen Schichten landet und dort einen Anreiz gibt, den Empfängerstatus über Generationen fortzusetzen.

- “Fourth, macroeconomic and financial sector policy can be reformed in favour of the left behind. That means sustaining a ‘high-pressure economy’ to keep job creation high, in the knowledge that those on the margins of the job market are fired first in a recession and hired last in a recovery. Governments and central banks must stimulate demand strongly for a long time after the lockdowns end, with debts restructured so they do not hold back investment.” – bto: Was bedeutet das konkret?

- “(…) greater policy efforts are needed to give regions, where possible, a critical mass of knowledge jobs so they can connect with the leading economic activity in national centres.” – bto: planwirtschaftliche Arbeitsplatzschaffung. Klar, das klappt bestimmt …

Ich denke, diese Ideen sind nicht falsch. Sie vernachlässigen aber zwei wichtige Ursachen. Bei den Vermögen die Geldwirtschaft, bei den “Zurückgebliebenen” die demografische Zusammensetzung.