Wege aus der Schuldenfalle

Wir stehen bekanntlich vor dem monetären Endspiel, was man eher ein Schulden-Endspiel nennen sollte.

→ Das monetäre Endspiel wird vorbereitet

→ Das monetäre Endspiel wird vorbereitet (II)

Vor einigen Tagen habe ich an dieser Stelle die Überlegungen von Steve Keen zu einem modernen Jubeljahr veröffentlicht und auch in der entsprechenden Podcast-Folge mit ihm diskutiert.

Er ist nicht der Einzige, der sich über Schulden Gedanken macht. In einer Studie zeigen Thomas Mayer und Gunther Schnabl auf, wie man die hohen staatlichen Schulden abbauen könnte. Die Highlights:

- “In the past, high levels of government debt were the origin of sovereign debt crises (Reinhart and Rogoff 2011). Therefore, a group of 110 ten economists recently proposed to devalue the government debt in the balance sheet of the Eurosystem – i.e. the European Central Bank and the euro area national central banks – to create new room for social and “green” expenditure for protection of the environment. The move has triggered a discussion about the sustainability of government debt and possible ways to reduce it.” – bto: Die Sinnhaftigkeit haben wir an dieser Stelle bereits ausführlich diskutiert. Es ist problematisch, einfach die Schulden auf der Bilanz der EZB abzuschreiben – und es wäre trotz der Aufkäufe der letzten Jahre ein zu geringer Anteil der Staatsschulden, der so entfiele.

Deshalb zu den Optionen.

Beginnen wir mit Option 1: Sparen. Ich muss gestehen, dass ich das immer ausgeschlossen habe, aber die Autoren haben doch Beispiele gefunden:

- „The most straightforward approach to reduce debt is economic austerity. Government expenditure is cut, or revenue raised, to depress public expenditure below revenue. If economic reforms reanimate growth, public debt as share of GDP declines even further.” – bto: also Sparsamkeit, während die Wirtschaft dank Reformen performt. Wir wissen aus Italien, wie schwer das ist. Trotz anhaltender Primärüberschüsse sind die Schuldenquoten nicht gesunken, sondern gestiegen. Es fehlte einfach am Wachstum. Und es spricht viel dafür, dass das Wachstum auch nicht nur deshalb so gering war, weil der Staat gespart hat.

- „Italy (…) after the World War I (…) had accumulated a huge debt amounting to around 180% of its gross domestic product (GDP) (Figure 3). The lira’s exchange rate plummeted, and inflation rose. In October 1922, Benito Mussolini (…) decreed a change of course in economic policy to what today would probably be called ‘austerity policies’ but was labelled then ‘liberal orthodoxy’. Government spending was reduced, social spending was cut, and real wages were diminished by 20 per cent between 1921 and 1929. The fascist trade unions made it possible. Taxes on consumption were increased, while taxes on corporate profits were reduced. State-owned enterprises were privatized. (…) The results of Mussolini’s policies were continuous surpluses of the state budget from 1923 to 1934 and a halving of the national debt ratio to around 76% of GDP by 1940.” – bto: Nun, es ist schwer vorstellbar, dass eine solche Politik heutzutage auch nur eine Wahlperiode durchzuhalten wäre. Man blicke auf das Schicksal Gerhard Schröders und die Gelb-Westen-Bewegung in Frankreich. Dazu sind unsere Gesellschaften zu sehr in der sozialen Illusion gefangen.

- Weiteres Beispiel: Deutschland in den letzten Jahren: „Public spending was curtailed starting in the late 1990s, and comprehensive economic reforms were launched in 2003 (under the title “Agenda 2010) by the government of Gerhard Schröder. The reforms were based on three pillars: labor market reforms, cuts of (future) social benefits, and incentives for private retirement provision. (…) As fiscal austerity depressed investment activity, growth declined, and tax revenues remained sluggish. The current account balance turned to a surplus as capital outflows strongly accelerated, boosted by strong interest rate cuts of the ECB combined with growing savings of households due to tax incentives. Enterprise savings were stimulated as the labor market reforms had created a large low-wage sector, which constrained overall wage increases. Only as of 2010 growth picked up and the general government debt level as percent of GDP started to decline.” – bto: und zwar – wie die Autoren ausführen –, weil das Ausland entsprechend mehr bei uns eingekauft hat. Es hat also deshalb funktioniert, weil wir exportieren konnten – getrieben von billigem Geld und (stark) steigender Verschuldung in den Abnehmerländern.

- Was dann zum Sparen in der Eurozone führte: „When the capital inflows into Southern and Eastern Europe abated with the outbreak of the Great Financial crisis in 2007/08, public expenditure levels and house prices proved unsustainable in the periphery of the euro area. Owing to falling house prices and soaring bad loans in domestic banks, the governments in the affected countries faced high costs of bank recapitalization. The public debt levels strongly increased. As they exceeded the Maastricht limit of 60% of GDP in most crisis countries, governments were forced to take fiscal austerity measures. (…) Membership in the European Monetary Union prevented the euro area crisis countries from improving their international competitiveness by depreciating their currencies to lower relative real wages. Thus, all crisis countries, except Italy, had to curtail their government expenditure compared to the year 2008. (…) This depressed income and GDP growth and undermined attempts to reduce public debt relative to GDP. The European Central Bank provided indirect financial assistance through its policy pf easy money. However, instead of helping necessary adjustment, this eased pressures for reform in most crisis countries. (…) Crisis countries encountered balances of payments deficits, but intra-Eurosystem credit provision through the TARGET2 payment system allowed the unlimited financing of these deficits at very low costs.” – bto: Es war also in der Eurozone eigentlich keine Lösung, sondern eine zwangsweise Kreditvergabe im Euroraum, was deshalb nötig war, weil die Wirtschaften nicht wie früher abwerten konnten, um die Probleme zu bewältigen.

- „In Germany, the loose monetary policy of the ECB in response to the European financial and debt crisis has caused (via low interest rates) a real estate and (via euro deprecation) an export boom since 2012. This boosted tax revenues and allowed to achieve a balanced budget – labeled ‘black zero’ – before the Corona crisis, despite a strong expansion of public expenditures. Debt as percent of GDP declined thanks to the benign monetary conditions, which reduced government interest payments and boosted economic activity.” – bto: Genauso ist es! Es war überhaupt keine Leistung!

Fazit aus meiner Sicht: Ja, es gab Fälle, in denen man durch Sparsamkeit die Schuldenquoten gesenkt hat. Aber dies nur, wenn das Wachstum von außen stimuliert wurde. Dies gilt besonders für die Lage in Deutschland seit 2010.

Damit kommen wir zu den „versteckten Wegen der Schuldenreduktion“: Exit Via Hidden Debt Reduction.

- Dazu grundsätzlich: „When inflation rises above interest rates, it becomes a hidden tax on holding money balances. Interest groups, which profit from inflation and financial repression, exert pressure in favor of monetary expansion. Given time lags in tax collection, higher inflation reduces the real value of tax revenues (Keynes-Tanzi effect), further shifting the focus of government financing to the central bank. The process of tax collection via inflation is arbitrary (Keynes 1920, Rothbard 1994). Keeping interest rates artificially low and inflation elevated can be an adequate exit strategy, yet at the risk of paralyzing growth via zombification.” – bto: Und diese Zombifizierung sehen wir ja schon seit Längerem, zumindest wenn man der BIZ glaubt. Die EZB sieht sie ja nicht und auch keinen eigenen Beitrag an der Verbreitung. Richtig ist aber, dass das mit der Entschuldung gar nicht so leicht ist, eben wegen des Time-Lags und dass es immer eine Art von Steuer ist. Aber eben eine nicht gerechte.

Dazu haben sich Mayer und Schnabl auch einige Beispiele angeschaut:

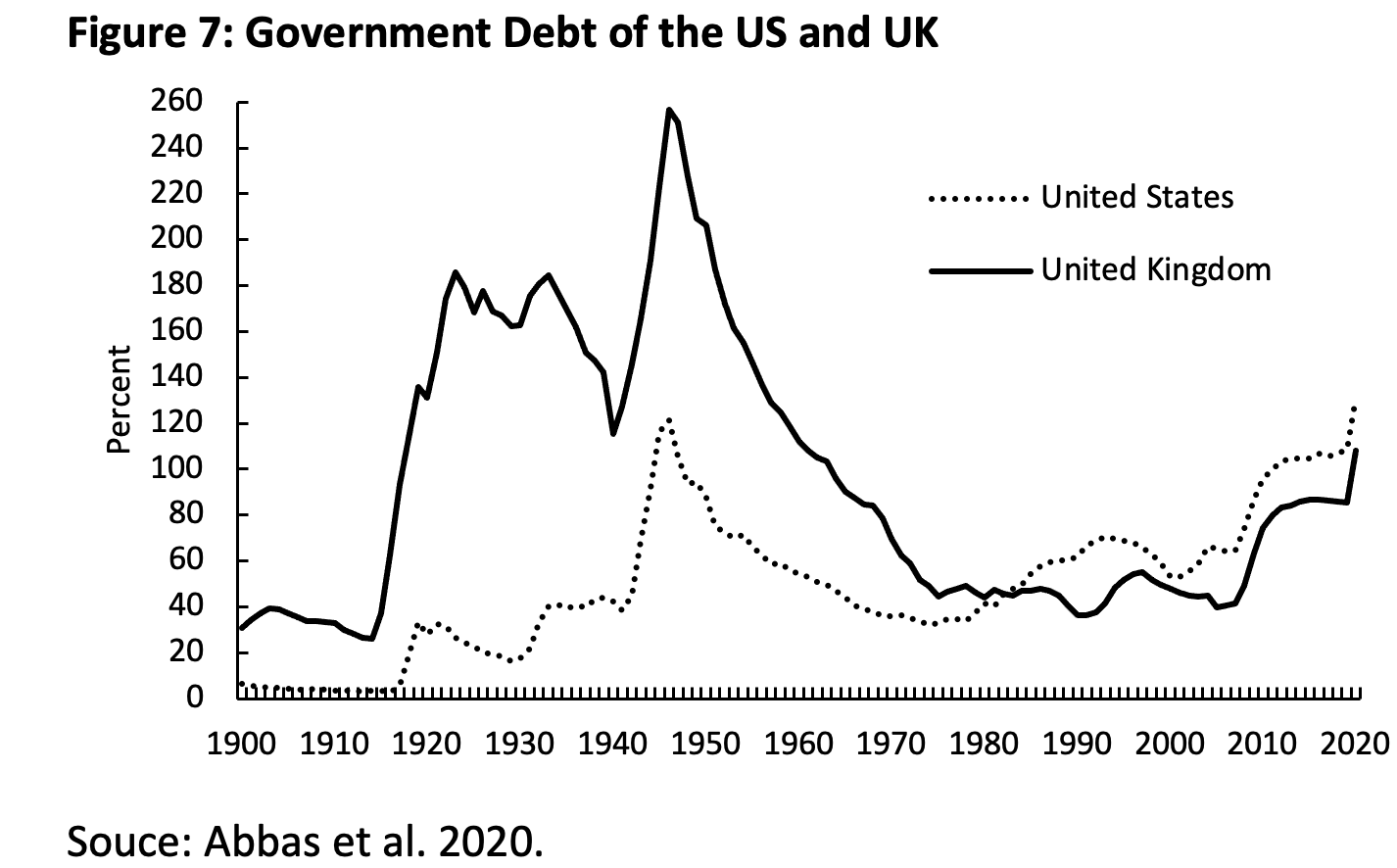

Financial Repression after World War II

- “Financial repression – i.e. policies that keep the return to savers below the inflation rate to allow banks to provide cheap loans to governments and enterprises – is a way to reduce government debt. The United States and the United Kingdom successfully reduced their post-World War-II debt burdens by keeping interest rates on government debt (i) below the growth rate g (i<g).” – bto: Das funktionierte damals und ich habe in “Coronomics” eine Studie der UCL zitiert, die nicht nur gezeigt hat, dass es klappt, sondern auch, dass es keine so ungewöhnliche Vorgehensweise ist. Ich bin sicher, dass es heute genauso probiert wird.

Figure 7: Government Debt of the US and UK

- “It was reduced again with two measures. First, the central banks of the United States and the United Kingdom pursued interest rate targets based on guidance by their ministries of finance. Government regulation capped interest rates on savings deposits and put a ceiling on banks’ lending rates. Second, multiple layers of regulation created a captive environment that directed credit to the government. Capital account restrictions and foreign exchange controls created a ‘home bias’ for financial investment. ‘Prudential’ regulatory measures required institutions to hold government debt. Transaction taxes on equities discouraged alternative investment classes.” – bto: Und auch heute kann man fest mit Kapitalverkehrskontrollen rechnen. Der IWF hat diese schon vor einiger Zeit als legitim eingestuft. Diese sind nur dann nicht nötig, wenn alle großen Währungsräume das Gleiche tun – ein Gedanke, den William White im Gespräch mit mir äußerte.

- Hinzu kam neben der moderaten Inflation vor allem reales Wachstum: „At the same time, growth was bolstered by the reintegration of military personnel in the civilian sector and the application of the technologies developed during the war. In addition, the post-war reconstruction in Europe and Japan combined with extensive market-oriented reforms gave a strong boost to the global economy. The stabilization of exchange rates combined with the liberalization of global trade provided an important growth stimulus for the member states of the Bretton-Woods-System. European countries benefitted also from the process of European integration.” – bto: So gesehen fällt diese Zeit auch etwas in das Beispiel von “Herauswachsen“. Die Frage ist nur, ob sich das entsprechend wiederholen lässt.

- „In the emerging market economies financial repression during the same time period did not reduce public debt. (…) a negative link between financial repression and economic growth, as extensive controls over the flow of money and credit were organized to serve the governments. (…) Highly uncompetitive domestic industries – often dominated by large state-owned enterprises –, were protected by high effective tariffs, which prevented them from realizing economies of scale. The outcome was low growth (…).” – bto: Das bedeutet, finanzielle Repression funktioniert nur bei einer wachstumsfreundlichen Politik. Und hier dürfte die EU nach allem, was man derzeit sieht, nicht dem Vorbild der USA nach dem Zweitem Weltkrieg folgen, sondern eher dem repressiven Kurs der Schwellenländer, weil es ja darum geht, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im gewünschten Sinne umzubauen.

- So auch die Autoren: „Today, conditions in the industrialized countries seem to converge to those in the less developed economies of the 1950s to 1970s. Financial repression, growing regulation and the gradual build-up of trade barriers has come along with low growth. Growth has declined along with interest rates. The monetary policies of the central banks introduced a quasi-soft budget constraint on enterprises, which undermines the efficient allocation of resources and paralyses growth. Therefore, debt levels do not decline despite a high degree of financial repression.” – bto: was aber nicht zu einer Umkehr der Politik führt. Im Gegenteil, sie wird verschärft.

Die Extremversion ist bekanntlich die Hyperinflation with Budget Reform in Post-World War I Germany.

- „While financial repression leads to a gradual transfer of wealth from creditors to debtors and a gradual erosion of trust in money, hyperinflation does this at a high speed. As rising inflation reduces the purchasing power of people, it often causes wage-price-spirals: Workers aim to maintain their real wages by pushing for higher nominal wages, while enterprises increase prices to maintain their mark-ups of prices over wages. With prices rising, growing demand for money prompts central banks to increase the money supply further. As the increase in inflation accelerates, domestic currency is substituted by more stable foreign currency. The resulting depreciation accelerates inflation as prices for imported goods rise. Demand for currency declines, and even more so, when high inflation provides an incentive for barter trade. Good money drives out bad money, the opposite of ‘Gresham’s Law’, which Bernholz calls ‘Thier’s Law’.” – bto: Das ist eine extreme Version der Entschuldung und aus vielerlei Gründen nur als Unfall denkbar, den selbst ich für sehr unwahrscheinlich halte.

- Sie hat aber geklappt. Mit der Einführung der Rentenmark konnte sich der Staat allen Verpflichtungen entledigen: „As a result, the government was able to buy back its many trillions of Reichsmark debt for only 190 millions of Rentenmark. Public debt fell to zero. The government gained the possibility to stop central-bank financed government expenditure.” – bto: Der gesellschaftliche Preis war bekanntlich enorm.

Auch später gab es noch “Inflationslösungen“: Inflation Without Budget Reform in Argentina.

- „Since the 1980s, Argentina has inter alia gone through five types of defaults without being able to establish sound government finances. (…) peso-denominated debt not indexed to inflation, which is for instance held by the private sector, public social security institutions and the central bank, has been devalued through inflation. The accumulation of government bonds by the central bank has usually been financed by monetary expansion. This has pushed up consumer price inflation and thus reduced public debt in real terms. Inflation has been reinforced by the depreciation of the exchange rate, as prices for imported products went up. With rising inflation, nominal GDP increased, and public debt as percent of GDP declined. This was particularly the case during the debt crisis in 1990/91, 2002/03 and since 2018. Therefore, bonds denominated in domestic currency were indexed to inflation.” – bto: Man kann es eben nicht beliebig wiederholen. Das Vertrauen der Sparer geht naturgemäß verloren.

- Sodann erklären die Autoren die weiteren Maßnahmen, die die Regierungen ergriffen hat: Kapitalverkehrskontrollen, Transfer der Dollarguthaben der Notenbank an den Staat (im Gegenzug erhielt diese uneinbringbare Forderungen) und letztlich die hohe Verschuldung in ausländischer Währung, was schiefgehen muss: „as dollar debt held in foreign countries can neither be reduced by inflation nor by exchange rate depreciation, outright defaults and debt-write-offs have inter alia occurred in the years 1982, 1989, 2001 and since 2020. The international defaults were preceded by longer periods of capital inflows and increasing international debt. Strong depreciations inflated dollar-denominated debt in terms of domestic currency. The crises were usually resolved by the restructuring of international debt and the provision of international public credit, inter alia by the IMF. By early 2020, Argentina’s debt to international multilateral public institutions stood at 73 billion US dollars. This implies that the burden of restructuring has been shifted to the taxpayers in the industrialized countries.” – bto: was auch eine “hidden debt reduction” ist, hier nun zulasten der internationalen Gläubiger.

Die nächste Option der Autoren sind die Cold Turkey Strategies. Wie der Name schon erahnen lässt, kein gemütliches Programm …

- „As long as government expenditures are high, the pressure on central banks to contribute to government financing is strong. Therefore, in the past, currency reforms were combined with a fundamental restructuring of government expenditures, a changing of the status of the central bank, and market-based economic reforms.” – bto: Dazu muss aber die Lage schon so ausweglos sein, dass es politisch umsetzbar ist. Die Beispiele fallen auch in diese Kategorie:

1948 Economic and Currency Reform in Western Germany

- “In early 1948, the German economy was in dire straits. As a result of extensive war damage, manufacturing production was less than 60% of its 1936 level and real per capita consumption was about two thirds of what it had been then; there was a severe scarcity of most basic goods. Moreover, war financing had left the ‘Third Reich’s’ public debt at the end of the war at almost 248% of 1939 GNP and had created a vast amount of excess liquidity. The Reichsmark (RM) had lost its function as a means of exchange, and barter trade had become the order of the day.” – bto: Es war ein offensichtlicher Staatsbankrott.

- “(…) currency reform was selected as the appropriate approach. The controlled reduction in the money supply would mop up excess liquidity and reduce the risk of an inflationary spiral. It would also allow accompanying measures to offset, at least in part, the redistribution of wealth resulting from monetary reform.” – bto: durch den Lastenausgleich. Ein damals gerechtfertigtes Verfahren, aber in der heutigen Zeit völlig unnötig, wenngleich die Linken es dennoch unter dem Vorwand der Corona-Krise fordern.

- „The depreciation of all monetary assets and liabilities by 90 percent would, at a given level of prices for goods and real assets, create large windfall gains for net monetary debtors possessing goods and real assets at the expense of net monetary creditors. (Therefore, the plan) proposed to tax these gains, at a rate of 100 percent payable in annual installments, in the case of all private debtors and to transfer the proceeds to a special burden equalization fund (Lastenausgleich). A further tax, at a rate of 50 percent levied in the same way, on the remaining net assets was suggested to equalize the burden of war destruction and displacement. In effect, these taxes were designed so as to redistribute purchasing power derived from past wealth to purchasing power derived from labor and business activities.” – bto: Das war smart. Und in eine ähnliche Richtung kann man argumentieren, wenn man heute Vermögen höher besteuert, dafür aber Einkommen geringer. Und zwar deutlich geringer.

Eine weitere – und wie ich finde besonders interessante – Vorgehensweise ist der Chicago Plan und Central Bank Digital Currencies.

- “An innovative technique for government debt reduction through monetary reform was proposed in the so-called Chicago plan of 1933. In the credit money system, bank money (i.e., money on bank deposits) is backed by a rotating stock of credit. It is created when banks extend credit, and it is destroyed when credit is repaid (or lost). Credit crises occur when the process of rotation is interrupted (e.g. by mass defaults of debtors). The authors of the Chicago Plan proposed to replace the rotating stock of credit by commercial banks to private and public debtors by a fixed stock of government bonds held by the central bank. In this way, a large part of (net) government debt can be taken out of the market and permanently placed on the central bank’s balance sheet.” – bto: Es entsteht ein einmaliger Gewinn, der nicht nur so groß ist, dass er die Staatsschulden deckt, sondern auch die Privatschulden noch deutlich senken könnte.

- “In the wake of the financial crisis the Chicago Plan and related ideas have received renewed attention. However, the plan comes at a price in the form of a change in the way money is created. Money creation through credit extension by private banks is replaced by money creation through credit to the government by the central bank. So far policy makers have apparently deemed this price too high to pay and have shied away from money reform. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to consider it, especially as it could be combined with the introduction of central bank digital currencies to reduce government debt outstanding in the market.” – bto: Und noch besser: Das digitale Zentralbankgeld erlaubt die Überwachung des Konsums der Bürger bis hin zur Sicherung klimaschonenden Verhaltens.

- “For instance, a digital euro fully backed by claims on governments would have five important advantages: (1) a safe European common currency without the need to create political union; (2) a monetary order less prone to investment boom-bust cycles; (3) an end to the sovereign-bank doom loop; (4) the establishment of the euro as a key international currency; and (5) a reduction of public debt outstanding in the market.” – bto: und eben (6) die völlige Kontrolle über das Ausgabenverhalten der Bürger und die erleichterte Durchsetzung von Negativzinsen. Wahrhaft ein Traum.

- “Since government debt would be used for backing money with an asset, digitization of the euro offers the possibility to reduce the gross debt of the euro states and end the sovereign-bank doom loop. Recall that the central bank buys government bonds to create the central bank money for the secure deposit, which can be transferred peer-to-peer in the blockchain. Thus, government bonds on the central bank’s balance sheet to back the outstanding (digital) central bank money are permanently taken out of the market.” – bto: Es ist eine verlockende Überlegung.

- “(…) the ECB could acquire EUR 6 trillion government bonds against reserve money in total (i.e., some EUR 3 trillion in addition to its existing holdings), and keep these bonds on its balance sheet. Since the stock of bonds is permanently required as cover for the money stock, repayment would be suspended. Moreover, as interest income from the bonds would be returned to governments anyway, coupons could be reset to zero. With a zero coupon and infinite maturity the bonds would cease to count as government debt. Hence, outstanding market debt of euro area governments would fall to EUR 5 trillion or 42% of GDP.” – bto: Wer da nicht mitmacht, ist der Dumme. Deshalb ist es falsch, hierzulande “zu sparen”.

Und was erwarten die Autoren? Hier die Highlights ihres Outlooks:

- “The historic examples show that in the past episodes of excessive government expenditure financed by central banks have led to regime changes followed by monetary and fiscal consolidation. At the current levels of government debt, an exit from low interest rates is only possible, if debt of the highly indebted governments is reduced. In addition, to exit from financial repression central banks must be shielded from the pressure to bail out shacky financial institutions.” – bto: klare Zielsetzung.

- “Therefore, a combination of debt-reduction based on central bank digital currencies combined with (…) economic and financial liberalization would seem advisable. A regime change to 100% money as proposed in the Chicago Plan has never been tried. However, in view of the digitization of central bank money it would offer a less painful way to debt reduction and monetary consolidation than all the other regime changes of the past.” – bto: Das finde ich auch. Allerdings würde ich den Ansatz von Steve Keen mit Blick auf die Privatschulden hinzufügen. Dann haben wir den Reset.

Hier geht es zur Studie: