Was die EU-Grenzabgabe für Unternehmen bedeutet

In meinem Podcast vom kommenden Sonntag (21. November 2021) beschäftige ich mich mit intelligenter Klimapolitik. Im Zentrum der Diskussion: die sogenannte Grenzausgleichsabgabe, die die EU zum Schutz der eigenen Industrie (und zur Sicherung hoher Kosten für Bürger und Unternehmen) einführen möchte. Vorbereitend einige Beiträge. Ich beginne mit meinen Ex-Kollegen, die – ohne die gesamtwirtschaftlichen Folgen überhaupt zu bedenken – vorrechnen, was es denn bedeutet (Auszüge):

- „The concept of ‘carbon pricing’—levying a charge for each metric ton of carbon dioxide emitted by industry—is well embedded in many countries’ climate and sustainability policies. But the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, better known as a carbon border tax, is the first time pricing will apply equally to imports. As a result, the impact will reverberate through global value chains and could redefine the competitive balance between nations in many industries. It will also provide a renewed impetus for producers around the world to accelerate efforts to slash their carbon footprints.“ – bto: Es wird sicherlich die globalen Wertschöpfungsketten beeinflussen, denn Güter, die nicht in Europa abgenommen werden, sondern in anderen Regionen der Welt, werden auch nicht mehr in Europa gefertigt. Denn einen Rabatt für Exporteure bei den CO2-Kosten wäre mit den Regeln der WTO nicht vereinbar. Ergo: Unternehmen verlagern (noch mehr als bisher) Produktion in die Abnehmermärkte. Ob es umgekehrt in der Welt zu einem Anreiz kommt, ebenfalls CO2 zu sparen? Nun, die Unternehmen werden sich dort genau überlegen, ob es sich lohnt nach Europa zu liefern.

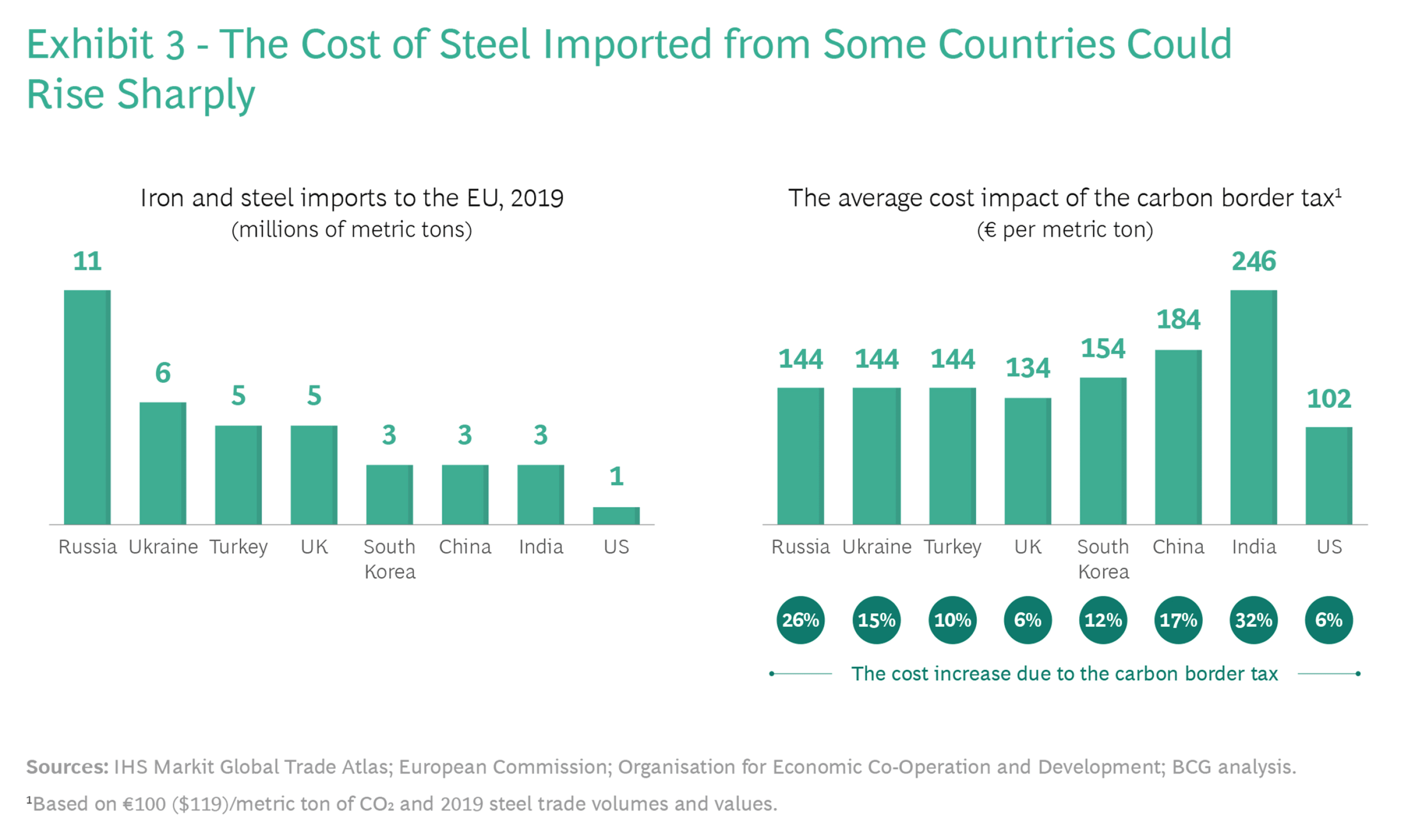

- “When the tax is fully implemented in January 2026, the biggest initial impact will be on the cost of such high-carbon inputs as steel, cement, aluminum, chemicals, and electricity; EU importers and non-EU producers of these inputs will be required to pay an estimated €75 per metric ton of CO2 emissions. This could increase the cost of materials made by more carbon-intensive producers, such as China, Russia, and India, by 15% to 30% overnight. And the effect will increase during subsequent years: the tax rate is projected to approach €100 per metric ton by 2030, and more products will likely fall within its scope at that point.” – bto: Und wie behandeln wir dann solche Fälle? Wie ein Stahlunternehmen, welches den CO2-Ausstoß in einem Lager bindet? Carbon Capture mögen wir doch nicht so. Oder anders behauptet, CO2-neutral zu sein? Es wird nur schwer im Einzelfall zu erklären sein.

- „The higher the carbon price rises, the more EU producers are put at risk of ‘carbon leakage’—losing out to cheaper imports from countries with less strict climate regulation. EU manufacturers have been receiving free carbon permits to compensate for carbon leakage. But these will now be phased out. Instead, the carbon border tax will be used to address this problem by reducing the attractiveness of offshoring as a means of avoiding EU climate costs.“ – bto: Es erhöht aber auch die Attraktivität von Offshoring aus der EU heraus für alle exportorientierten Unternehmen (nur mal so).

- „Under the new policy, importers will be required to purchase carbon import permits for each metric ton of CO2 brought into the EU through particular goods and materials. The tax liability will depend on both the carbon intensity of the import and the tax rate per metric ton—which will be the same as the domestic carbon price paid by EU producers. To avoid double taxation, goods imported from countries that have domestic carbon-pricing regimes similar to the EU’s will be exempt from the levy, subject to agreement between those countries and the European Commission.“ – bto: Da darf man gespannt sein. Die Bedeutung Europas als Markt ist hoch, aber der Anteil am Welt-BIP sinkt kontinuierlich. Die USA sind weit weg davon, einen CO2-Preis einzuführen. Und wenn es der Demokrat Joe Biden nicht macht, dann sicherlich nicht ein republikanischer Nachfolger und der muss nicht mal Donald Trump heißen.

- „The tax will be implemented in stages. January 2023 through December 2025 will serve as a transitional phase. During this time, importers of steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, and electricity must calculate and report their emissions—but will not yet have to pay a carbon tax. In the second stage, which will commence in January 2026, companies will have to purchase import permits.“ – bto: Beim Berechnen fällt dann auf, wie sinnvoll es doch ist, woanders zu produzieren. Die EU hat – vor allem dank Deutschland – noch einen Handelsüberschuss. Der wäre dann weg, wenn die Lasermaschinen etc. nicht mehr hier hergestellt werden.

- „Even though the full financial impact won’t hit until 2026, importers will start facing considerable administrative burdens in January 2023. They must develop mechanisms to calculate the emissions contained within their products and have this data independently verified. In addition, they will need to ensure that emissions are properly declared to the appropriate authorities. Importers will be held liable if they do not follow the rules.“ – bto: Das bedeutet, dass die EU hier sogenannte non-tarifäre Hemmnisse errichtet. Das nennen andere Protektionismus. Und es dürfte auch so aufgefasst werden. Wir werden entsprechende Gegenmaßnahmen erleben.

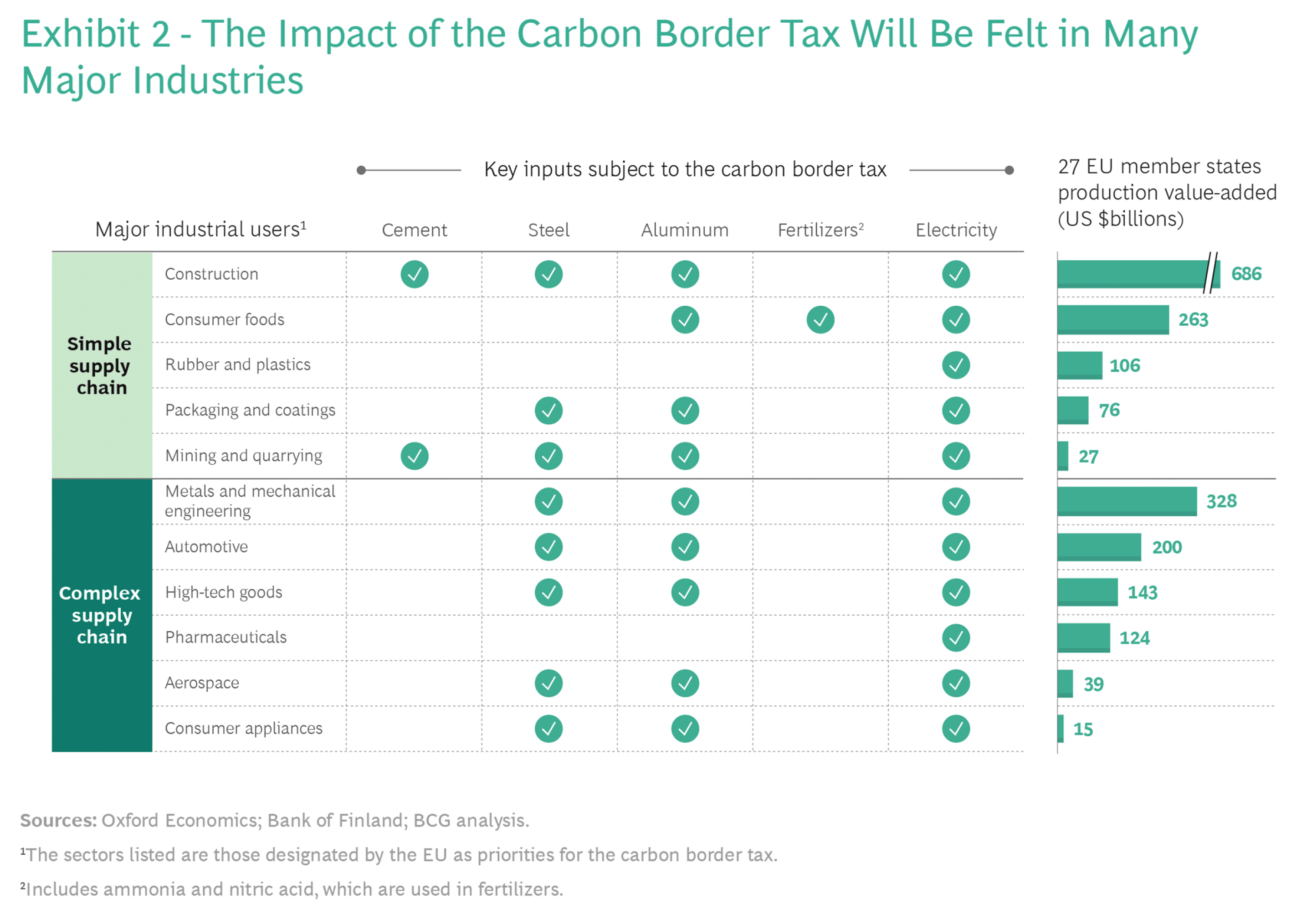

- “BCG’s initial assessment of the impact suggests that it will fall most heavily on the supply chains of such industrial sectors as automotive, construction, packaging, and consumer appliances. These industries’ costs for key inputs such as steel and aluminum will rise, and companies will need to take action to maintain competitiveness.” – bto: na ja, oder auch nicht. Wir bekommen halt Stagflation: höhere Preise und weniger Nachfrage.

Quelle: BCG

- “This cost impact will drive end consumers to change their purchasing behavior, which will affect the relative competitiveness of non-EU companies that export these products to the region. Less carbon-intensive producers will pay a lower tax rate, and their products will become more attractive in the EU market.” – bto: Das scheitert am Nachweis. Wie will die EU überprüfen, ob das chinesische Auto mit grünem Stahl gebaut wurde? Wie geht die EU mit der Situation um, dass der grüne Strom aus einem der neuen chinesischen Atomkraftwerke stammt? Denn nicht die ganze Welt verhält sich so ideologisch.

- „There are also implications for EU producers. As free carbon permits are phased out, these companies will have to pay the full carbon costs of the entirety of their production—including exports. This means they will compete in some non-EU markets with local producers that have not paid full carbon costs, leading to a potential cost differential. To address this issue, companies in some EU sectors, such as steel, have called for a carbon price rebate on exports. But the European Commission has not agreed.“ – bto: weil die WTO das verbietet. Folge: Migration in der EU zu günstigem CO2-neutralen Strom (Frankreich – Atom, Schweden – Wasserkraft) oder aus der EU heraus. Das ist ein massives De-Industrialisierungsprogramm für die EU, vor allem Deutschland.

- „Steel imported from more carbon-intensive producers will become proportionally more expensive than that from low-carbon manufacturers. While Russian steel exporters can expect to pay €147 per metric ton, for example, US steel producers will pay about €103. Based on 2019 steel prices, the average percentage increase for producers in different nations could range from 6% to 32%.“ – bto: Das führt zu einer anderen Aufteilung des Weltmarktes. Die Stahlhersteller werden so die Märkte bearbeiten, dass der mit den geringeren CO2-Kosten zu einem höheren Preis nach Europa liefert, weil der mit den höheren CO2-Kosten den Marktpreis definiert. Was für eine Freude!

- “Given that EU steel producers will also face the phaseout of free carbon permits just as the new tax comes into force, the sector’s domestic carbon costs will start rising sharply in 2026. Unless EU producers take further action to decarbonize, we estimate that carbon will cost the industry about €11 billion annually by 2030, assuming prices rise to the equivalent of €100 per metric ton by that point.“ – bto: Glücklich, wer Atomstrom in Frankreich bekommt …

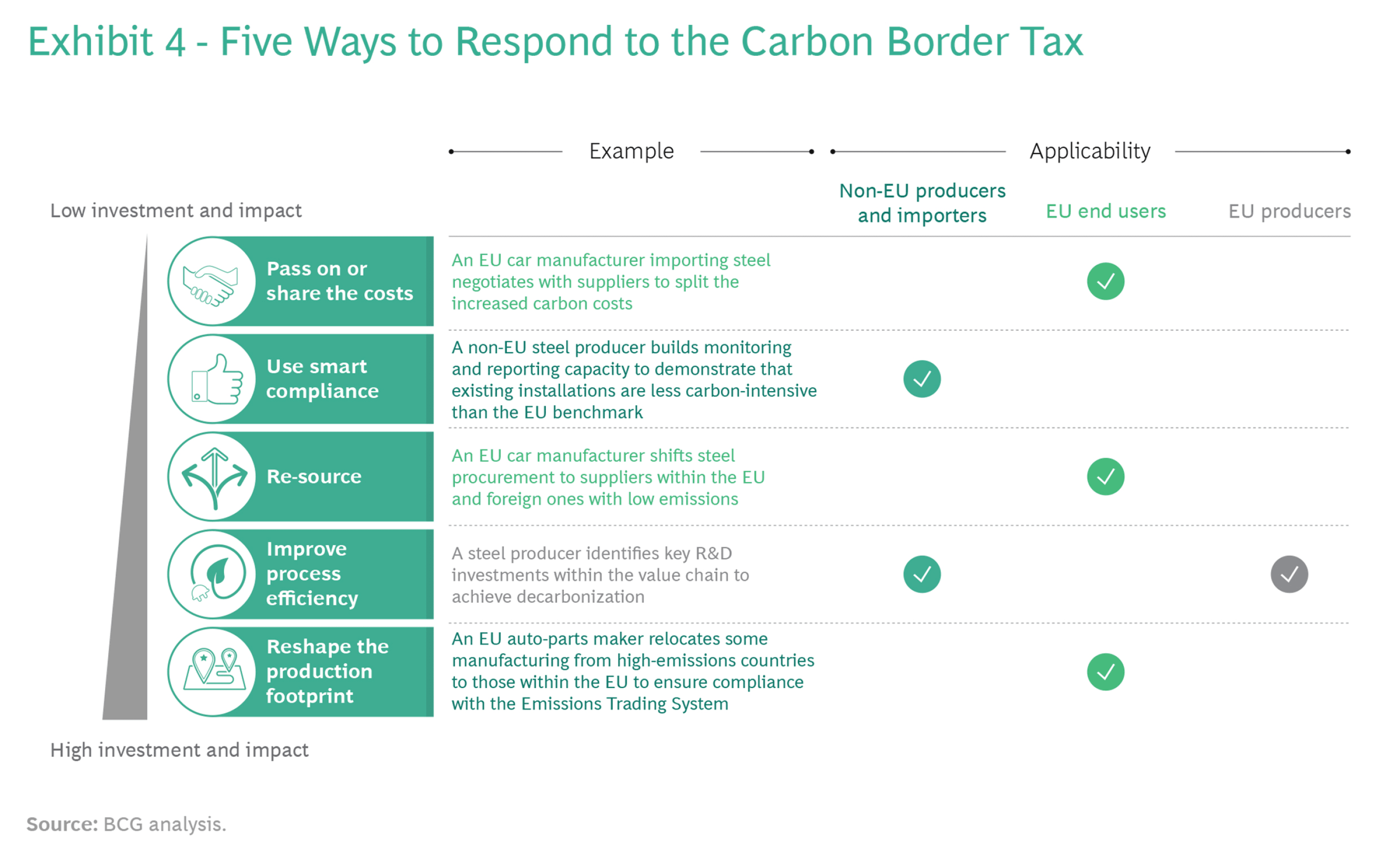

Und dann haben die Ex-Kollegen (wenig überraschende) Empfehlungen, was Unternehmen denn tun sollen:

- “Pass on or share the costs. If the impact is relatively small, companies might be able to pass the increase on to end customers.

- Use smart compliance. An accurate calculation of the carbon emissions embedded in imports will be key.

- Re-source. (…) By establishing internal processes to measure the carbon impact of different options, manufacturers will be able to identify lower-carbon suppliers, whose products will therefore attract a lower carbon border tax.

- Improve process efficiency. Investing in more efficient industrial processes, or substituting higher-carbon materials with lower-carbon ones, will reduce the overall carbon footprint of a product (…).

- Reshape the production footprint. Consider whether the tax’s introduction changes the rationale for the current production footprint. Does offshoring still make sense once climate costs are equalized, for example, or is it better to bring some manufacturing back to the EU?“ – bto: Die richtige Frage ist, was produziere ich lieber woanders?! Und die fehlt! Gute Berater arbeiten vor dem Hintergrund dieser Aussichten an einer globalen Standortstrategie für Produktion, die nur Regionalisierung bedeuten kann mit einer möglichst weitgehenden Vermeidung der teuersten Region.

- “(…) companies should accept that the EU’s carbon border tax will quickly start to change the competitive dynamics in their industries and their entire value chains. Companies in the forefront of tackling carbon emissions will have a powerful strategic advantage in the new regulatory environment—and will have a head start as other nations adopt carbon-pricing mechanisms in the fight to mitigate climate change.” – bto: nein. Unternehmen, die sich regional ausrichten, sparen Ressourcen, werden künftig mehr verdienen und profitieren von intelligenterer Klimapolitik in anderen Regionen, die auf Innovation setzt und die Entwicklung neuer Technologien.

→ bcg.com: „The EU’s Carbon Border Tax Will Redefine Global Value Chains”, 12. Oktober 2021