Über-Ersparnis und Über-Exporte als Folge ungleicher Einkommensverteilung?

Eine teure Woche war das für die deutschen Steuerzahler. Mit Blick auf die “notwendige Sicherung unserer Exportmärkte” ist die Politik der Meinung, wir müssten für unsere Exporte auch selber bezahlen. So dieser (zumindest bei Twitter hoch-aktive) politische “Wirtschaftsfachmann”:

Was für ein Irrsinn! Meine Kritik an den deutschen Exportüberschüssen ist bekannt:

→ „Exportweltmeister“ – ein teurer Titel!

Vielmehr möchte ich die Verteilungswirkung der Politik in Erinnerung rufen: Wir subventionieren Eigentümer und Mitarbeiter der exportorientierten Unternehmen und nehmen als Gegenleistung Forderungen mit zunehmend zweifelhaftem Wert, mit denen wir geringe Erträge erwirtschaften (wenn überhaupt, TARGET2 beispielsweise zinslos) und müssen zugleich über eine Schulden- und Transferunion an die anderen Geld verschenken. Kein Wunder, dass wir ärmer sind.

Es geht aber auch weiter, wie ein neues Buch, “Trade Wars Are Class Wars”, erklärt. Handelsüberschüsse sind demnach getrieben durch eine falsche Verteilung von Einkommen im Inland zugunsten jener, die mehr verdienen und deshalb auch mehr sparen. Martin Wolf hat das Buch in der FINANCIAL TIMES (FT) besprochen. Auszüge:

- “‘Trade war is often presented as a war between countries. It is not: it is a conflict mainly between bankers and owners of financial assets on one side and ordinary households on the other — between the very rich and everyone else.’ This encapsulates the argument of Trade Wars Are Class Wars. Its authors Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis argue that what has been happening to trade and finance can only be understood in the context of domestic pathologies in leading economies. The result has been severe global imbalances, unsustainable debt and monstrous financial crises.” – bto: Die Frage ist die nach Henne und Ei. Ich denke jedoch, dass Anhäufen von Forderungen gegen schlechte Schuldner, wie wir das tun, ist selten dämlich.

- “‘For decades,’ note the authors, ‘real borrowing costs have been below long-term forecasts of real economic growth and remain around zero.’ This combination of extraordinarily low real interest rates with weak global demand and low inflation is a prime symptom of underconsumption or, in modern parlance, ‘a savings glut’. The explanation given by Klein, economics commentator at Barron’s, and Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, is that income has been shifted to wealthy people who do not spend what they earn.” – bto: Nun könnte man aus Klimaschutzgründen sagen, dass das gut ist, weil weniger Konsum hilft. Richtig ist allerdings, dass es spiegelbildlich zu immer mehr Verschuldung gekommen ist – und damit Geldschaffung. Dies führt auch zu einer Zinssenkungstendenz.

- “(…) the book’s core is the analysis of the history of China, Germany and the US over the past three decades. The economic success of China was the result of an extreme version of what the authors call the ‘high savings’ model of development, together with exploitation of trade opportunities, which Japan pioneered. Thus, from the early 1990s and particularly after 2000, there was a sharp decline in the share of household consumption in China’s gross domestic product.” – bto: und damit – so die Logik – der Kapitalexport in die USA, der zu den tiefen Zinsen beigetragen hat (und damit die Verschuldung befeuerte, so die Logik auch von Ex-Fed Chef Ben Bernanke).

- “Gross national savings reached a peak of close to 50 per cent of GDP. Until the global financial crisis, these savings went into domestic investment and the current account surplus. After the crisis, the decline in the surplus on the current account — the balance on trade in goods and all services — was offset by a further huge increase in credit-fuelled investment, which reached nearly half of GDP.” – bto: Aber es war mehr auf das Inland bezogen. Richtig ist, dass der Konsum in China wachsen muss, wobei der Umbau der Wirtschaft nicht leicht sein wird.

- “Now consider Germany. Since the end of the post-reunification boom of the 1990s and the labour market liberalisation of the 2000s, corporate profits have been high and domestic corporate investment weak. Remarkably, ‘[German] consumption did not grow at all between 2001 and 2005.’ Domestic spending fell far behind trade-fuelled income. The German government has, until Covid-19, also run a very tight budget. As a result, a gigantic and persistent current account surplus — excess savings, in other words — emerged.” – bto: richtig. Wenn alle inländischen Sektoren sparen, muss man Exportweltmeister sein.

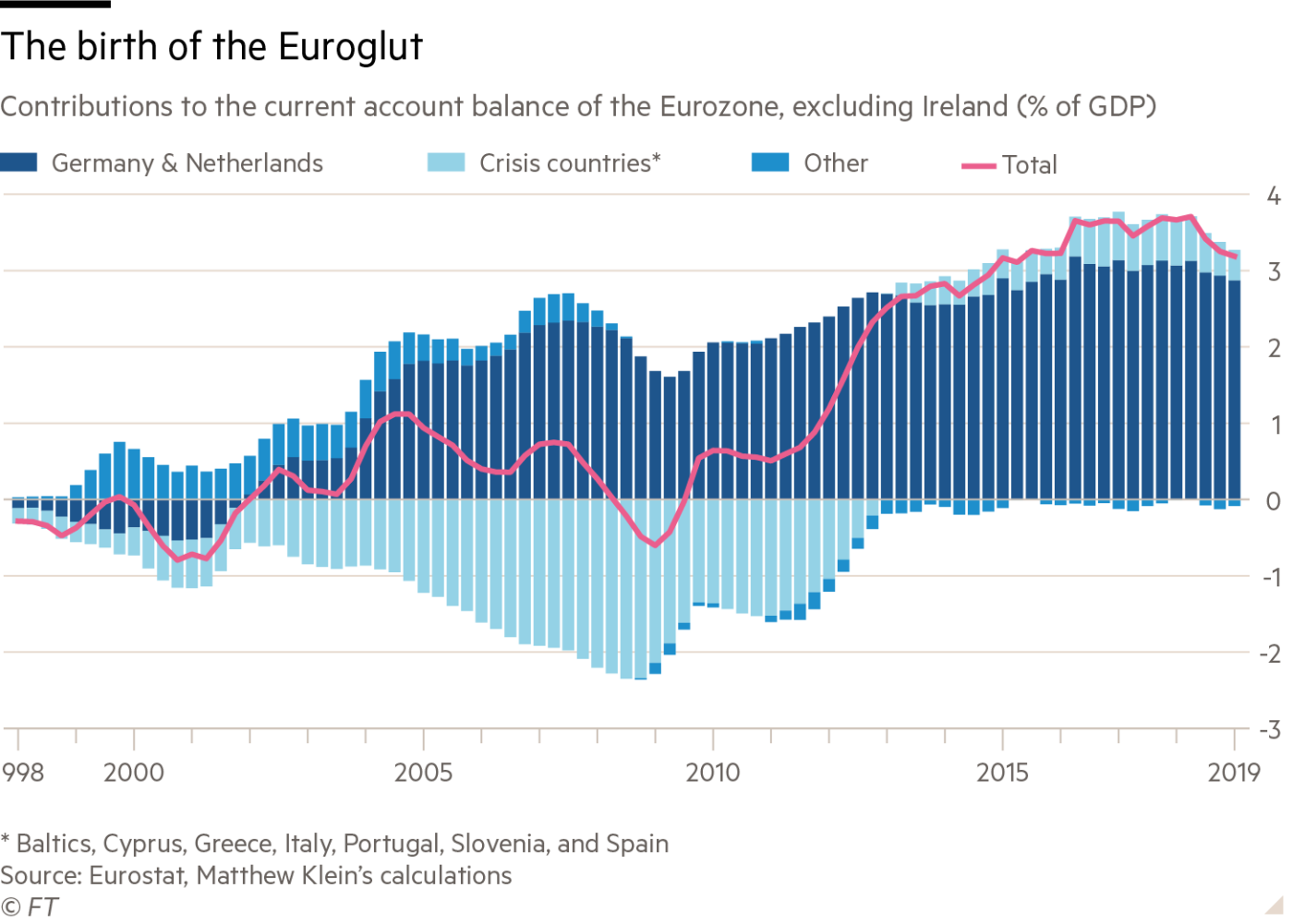

- “Until 2008, the excess savings of Germany and several other smaller European countries (such as the Netherlands) were offset by unsustainable credit and spending booms in countries such as Greece, Ireland and, above all, Spain.” – bto: So ist es. Aber es war der Verschuldungsboom, der wie ein Sauger gewirkt hat, auch angetrieben vom zu billigem Geld der EZB. Die Zinsen waren schlichtweg zu tief.

- “The global financial crisis ended that. Since then the entire eurozone has moved into a globally destabilising current account surplus, in a damaging attempt to turn the second-largest economy in the world into a bigger Germany in the midst of a global savings glut.” – bto: Natürlich ist das nicht gesund. Doch was wäre zu tun? Richtig: Wir müssen in Deutschland dringend mehr investieren und konsumieren. Das Problem ist aber die Abgabenlast und nicht die Einkommensverteilung. Der Staat nimmt den Bürgern viel zu viel ab.

Quelle: FT

- “What benefit have Germans obtained from their huge excess savings? Remarkably little. ‘Germans, who have been such avid exporters of financial capital over the past two decades, are almost uniquely bad at investing abroad,’ write the authors. ‘Since the start of 1999, the German private sector collectively spent a little over €5.1tn acquiring assets in other countries. Yet over the same period, the amount of these foreign assets grew by only €4.8tn.’ Over almost two decades, unwise purchases of US subprime mortgages and Greek sovereign debt have resulted in a valuation loss of 7 per cent. This is a fruitless form of frugality.” – bto: Genau das habe ich immer wieder kritisiert und die im obigen Link zitierte Studie zeigt, dass wir unser Geld sehr schlecht anlegen.

- “(…) the biggest and most persistent deficit country has been the US. Global supply and demand are balanced there, mainly by the Federal Reserve, in effect the world’s central bank. (…) With the current account deficit largely driven by external demand for safe US assets, the offsetting excess domestic demand has come from two sources: financial bubbles and the federal deficit.” – bto: Die USA machen vor, wie man konstant Defizite fährt und dennoch reich bleibt!

- “The housing bubble was particularly fascinating not only because of its disastrous end, but because of the way in which Wall Street generated the safe dollar-denominated assets the world wanted by alchemy: the conversion of bad mortgages into triple-A securities.” – bto: die vor allem die dummen Deutschen gekauft haben!

- “(…) the surplus savings of a number of countries drove a huge net capital inflow into the US, which resulted in a massive trade deficit and so ultimately, the loss of manufacturing jobs in the US heartland. It was the capital account that mattered. The trade balance was just the byproduct.” – bto: so wie auch bei uns der Exportüberschuss ein Abfallprodukt des Sparverhaltens ist.

- “The imbalances that caused the eurozone crisis, the debt explosions in the US and peripheral Europe, and again in post-financial-crisis China go back to two fundamental failures: the distribution of income away from the bulk of the population towards wealthy elites and the unique global role of the dollar.” – bto: In Deutschland stimmt das nicht. Es war die hohe Besteuerung der unteren und mittleren Einkommensgruppen, die den Konsum dämpft.

- “In the eurozone, this will probably require the creation of a central fiscal authority with capacity to redistribute resources.(bto: warum?? Das verstehe ich in diesem Zusammenhang überhaupt nicht) In Germany, it will require higher government spending on investment and welfare (bto: wieso das? Es bedeutet mehr Geld in den Taschen der Bürger!) In China, it will require the reform of property rights, improved rights for migrants to urban areas, a better social safety net, the ability of workers to organise and a shift of taxes on to the rich.” – bto: Da springen sie zu kurz.

→ ft.com (Anmeldung erforderlich): “Martin Wolf: what trade wars tell us”, 18. Juni 2013