Studie: Tiefe Zinsen Folge der säkularen Stagnation oder der Zentralbankpolitik?

Immer wieder habe ich bei bto die Ursachen der tiefen Zinsen diskutiert und durchaus die verschiedenen Perspektiven beleuchtet:

→ Die Gründe für sinkende Realzinsen

→ Säkulare Stagnation als Grund für tiefe Zinsen?

→ Zinsen hoch oder runter – was kommt?

→ Doch Freispruch für die Notenbanken?

→ Niedrigzinsen aus Mangel an sicheren Anlagen in überschuldeter Welt

→ „Tiefe Zinsen bis der Ketchup spritzt“

→ Niedrigzinsen: Die Badewannen-Theorie springt zu kurz

→ Warum sind die Zinsen so tief?

Nun eine neue Studie von Thomas Mayer gemeinsam mit Gunther Schnabl von der Uni Leipzig, einem anerkannten Kritiker der Politik der Zentralbanken und einem ausgewiesenen Experten für Japan. Man kann so gesehen die Antwort auf die Frage, wer die Schuld für die Entwicklung trägt, ahnen, allerdings mit einer guten Begründung. Sehen wir uns die Studie an:

- „Based on Keynes (1936) and Hansen (1939), Bernanke (2005) and Summers (2014) have attributed secularly declining real interest rates to a global savings glut driven by ageing societies, a declining demand for fixed capital investment, and a declining marginal efficiency of fixed capital investment (Gordon 2012). Lukasz and Summers (2019) argue that ‘the neutral real rate for the industrial world has trended downward for the last generation and this is best understood in terms of changes in private sector saving and investment propensities’. In this view, by setting the interest rate to or below zero central banks simply adjust to the exogenous forces of the secular stagnation.” – bto: Das ist das, was ich in einem Kommentar mal die Badewannen-Theorie genannt habe. Ich finde sie allein schon deshalb nicht überzeugend, weil Kreditvergabe am Anfang der Geldschöpfung steht und nicht am Ende und deshalb diese Sicht die Wirkung der hohen Verschuldung völlig übersieht.

- „(…) from the point of view of Austrian economic theory according to Mises (1912) and Hayek (1931), human beings strive to achieve their goals rather earlier than later and therefore have a positive time preference. This makes negative interest rates under free market conditions impossible (Mises 1940). This proposition is in line with the finding of Homer and Sylla (2005) that through most of economic history real interest rates were positive. In this spirit, based on the monetary overinvestment theories of Mises (1912) and Hayek (1931) and in line with Borio and White (2004) and White (2006), Schnabl (2019) has argued that the gradual decline of interest rates in the industrialized countries has been due to asymmetric monetary policies, i.e. strong interest rate cuts during crises, which were not followed by respective interest rate increases during the post-crisis recoveries.” – bto: Vor allem Borio und White ragen hier heraus, sind bzw. waren sie doch bei der Bank für Internationalen Zahlungsausgleich (BIZ) tätig. Letzterer hat immer wieder und richtigerweise vor der Finanzkrise gewarnt.

The Keynesian and Neoclassical Interpretation of Low-Interest Rates and Growth

Die Autoren untersuchen zunächst die erste Theorie und für die Besprechung bei bto empfiehlt es sich, bei der Struktur zu bleiben:

- “Bernanke (2005) attributed an increasing US current account deficit (i.e. growing net capital inflows to the US) and the decline of world interest rates to factors outside the US (He) argued that ageing populations in a number of industrial countries and several emerging market economies such as China had shifted these countries from net borrowers on international capital markets to net lenders, thereby inflating net capital flows to the US. (…) pre-subprime crisis pull factors attracting capital flows to the US were fast productivity growth, strong property rights, and a robust regulatory environment.” – bto: Dem kann man durchaus folgen. Gerade, wenn man in einem Land mit unsicherem Rechtssystem lebt, ist es sehr attraktiv, Teile des Kapitals in einem sicheren Umfeld anzulegen.

- “Summers (2014) linked a shrinking demand for fixed capital investment to changes in technology, with IT-related companies being assumed to have a lower demand for capital. Like Bernanke (2005) and Gordon (2012) he argued that the potential of innovations to increase productivity had been structurally declining. The resulting decline in the demand for capital goods was supposed to have come along with declining prices for capital goods, therefore leading to a further decline in nominal investment. As household savings rise, they drag down, in the view of Summers (2014), expected aggregate demand and declining investments derived from these exogenously set ‘stylized facts’, the savings curve in a neoclassical capital market setting shifts to the right and the investment curve shifts to the left.” – bto: Weniger Nachfrage und mehr Angebot führen dazu, dass die Zinsen sinken. Ich könnte mir auch denken, dass durch zu viele Schulden Einkommen entstanden, die nicht mehr verwendet werden konnten und es deshalb zu einer abnehmenden Produktivität neuer Schulden kam.

- “Given a negative output gap and declining consumer price inflation (the) compiled natural or neutral interest rate declines since the 1980s. The decline accelerates since the 2007/2008 global financial crisis, turning negative recently. This trend is confirmed by the estimations of Jordá and Taylor (2019), who argue that half of the trend is due to structural factors such as productivity growth and demography and half of the trend is due to central banks.” – bto: Mit dem Modell lässt sich demnach in sich konsistent ableiten, dass die strukturellen Zinsen aufgrund dieser externen Faktoren sinken (und die Notenbanken nur einen kleinen Anteil haben).

- “In the seminal Keynesian framework, consumption is determined by real income (Y), with the propensity to consume declining over time (as in Keynes 1936). Bernanke (2005) and Summers (2014) argue that the propensity to consume (propensity to save) declines (increases), when the population is aging and the working age population is shrinking.” – bto: Prinzipiell kann man dem auch folgen. Allerdings kommt dann bald die Zeit, in der die ältere Generation mehr “entspart”, also die Zinsen steigen und die Assetpreise fallen müssten.

- “In this framework, if a society is ageing, the propensity to consume k decreases. The price level and output fall. To compensate this effect, a central bank pursuing an inflation target needs to decrease the real interest rate to increase investment, output and thereby the price level again, as explained by Laubach and Williams (2015) as well as by Rachel and Summers (2019). Interest rate cuts are necessary to maintain the inflation target and an equilibrium in the goods market.” – bto: In diesem Modell kann es nur diese Schlussfolgerung geben und ich denke, sie ist auch zumindest partiell richtig. Aber es dürfte nicht genügen, weil die Grundursache in “meinem gedanklichen Modell” die Aufschuldung der letzten Jahrzehnte war.

Kommen wir zum alternativen Modell:

The Austrian Overinvestment Framework and the Role of the Financial Sector

- “The overinvestment theory by Mises (1912) and Hayek (1931) argues that an interest rate set below the natural interest rate causes an economic upswing, which turns into an economic downswing when interest rates are lifted to contain inflation. The unsustainable boom is transmitted via credit creation of the banking sector. If interest rates are strongly cut in response to the downswing, distorted economic structures are conserved, which leads to persistently low growth.” – bto: Nun muss man sagen, dass wir keine Inflation erlebt haben, was sicherlich an dem Angebotsschock durch die Globalisierung lag. Andererseits ist die Zombifizierung nun wirklich nicht zu leugnen.

- “In the Austrian overinvestment framework (Mises 1912, Hayek 1931), a boom is triggered when the central bank sets the interest rate below the natural interest rate. The natural interest rate is the interest rate, where savings are equivalent to investment (I=S). Initially, there are no structural distortions in the economy. An interest rate set by the central bank below the natural interest rate signals higher present savings and, as a result, higher consumption in the future. This provides an incentive to increase capacities for the production of consumption goods.” – bto: und legt damit die Wurzel für den deflationären Kollaps.

An dieser Stelle möchte ich erneut auf meine kleine Serie zur Eigentumsökonomik verweisen. Da spielt die Notenbank eine ähnliche Rolle. In dem sie Geld billiger macht, erhöht sie die Konkurrenz und zwingt Unternehmen, mehr zu investieren oder neue Produkte zu entwickeln, um damit im Markt zu bestehen, selbst wenn es sich noch gar nicht rechnet. Damit fördert sie die Überkapazitäten und eine immer höhere Verschuldung im System, was wiederum die Krisenanfälligkeit erhöht und damit noch mehr Eingriffe erforderlich macht.

- “In the overinvestment theory, if some enterprises start to invest in response to a lower interest rate, they need inputs from other enterprises, which extend their production capacities as well. A cumulative upswing sets in, which is financed by credit creation of banks. This allows real investment (I) to exceed temporarily real savings (S). Banks create additional credit to keep interest rates aligned with the central bank interest rate. In the first phase of the upswing, when not the full labor force is used, wages do not increase. The profits of banks and enterprises grow, which is reflected in rising stock prices. When unemployment has declined to a low level, the negotiating power of labor unions is strengthened and wages rise. Enterprises have to lift prices to cover their costs, which pushes up inflation. When rising inflation forces the central bank to lift interest rates, the benchmark for the profitability of past and future investment projects is raised.” – bto: Nur Letzteres ist in den vergangenen 30 Jahren nie passiert. Denn aus Angst vor der Krise wurde immer wieder gerettet, was eigentlich erst den großen Kreditboom auslöste.

- “Given higher financing costs, incomplete investment projects have to be abandoned, and new investment projects become unprofitable. A cumulative downswing evolves. During the downswing – according to the monetary overinvestment theory – the central bank keeps the credit rate via the central bank interest rate above the natural interest rate, which falls as investment declines. As the central bank interest rate is kept above the natural interest rate, the downturn is aggravated. As unemployment grows, wages and prices fall. The dismantling of investment projects with low profitability as well as falling wages and prices are seen as pre- requisites for the economic recovery. The downswing entails a cleansing effect (Schumpeter (1912), as resources can be shifted to higher return investment projects.” – bto: Genau das findet aber seit 30 Jahren nicht mehr statt. Eine Bereinigung kann man sich heute politisch gar nicht mehr vorstellen. Und deshalb werden die Probleme auch immer größer, abzulesen an den immer höheren Schulden relativ zum BIP.

- “During the upswing non-financial investment grows as low interest rates set by central banks signal higher present savings and thereby higher future consumption (Mises 1912, Hayek 1931). Resources are redirected from the production of consumer goods to the production of capital goods. Alternatively financial investment increases (…) speculation may set in, with the valuation of stocks becoming delinked from their fundamentals. A credit boom evolves, with prices of non-financial and financial investment rising. The speculative boom may also attract additional funds from abroad, as observed during the 2003 to 2007 US subprime boom and the boom in the southern European countries during the same time period.” – bto: Das klingt nach einer ziemlich plausiblen Beschreibung dessen, was wir in den letzten Jahren erlebt haben.

- “If central banks change interest rates in an asymmetric way – i.e. interest rates are cut more during the recession than they are lifted during the recovery after the crisis to prevent unemployment, interest rates will gradually decline towards zero (…) Also, the average productivity of investment would be affected (…) and growth dynamics would be weakened.” – bto: Die Zombifizierung führt dann zu dem, was als “säkulare Stagnation” oder als “Eiszeit” bezeichnet wird.

Und dann versuchen die Autoren, dem Problem empirisch auf den Grund zu gehen:

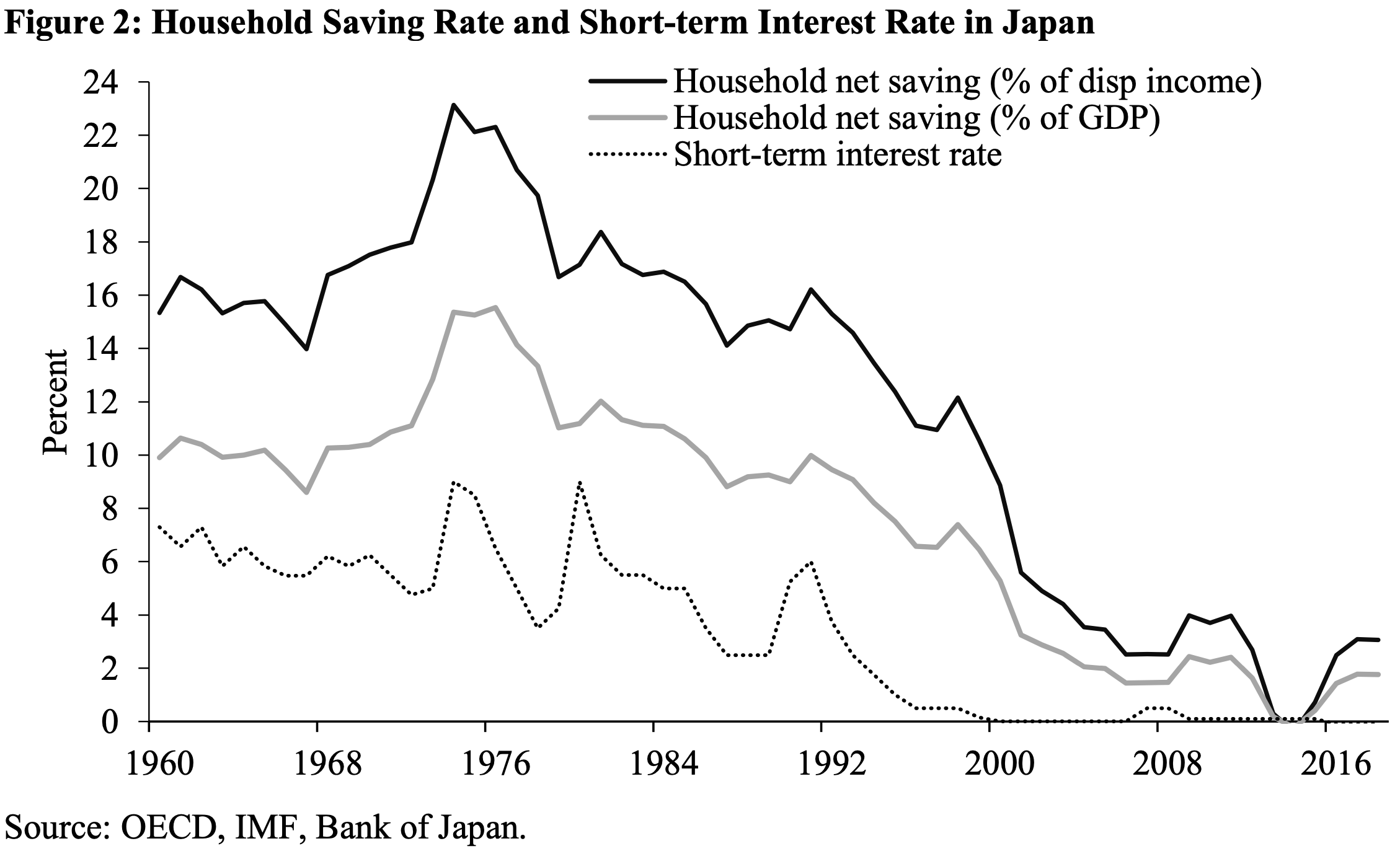

- “Empirically the link between ageing populations and household savings rates is weak. The most prominent example is Japan, where since the 1980s the fast ageing of the society has come along with declining household savings rates. Figure 2 shows that together with the short-term interest rate, which has been pushed down by the Bank of Japan to zero, household net savings in percent of GDP and of disposable income have declined as well.” – bto: Stimmt, das Bild passt dann natürlich nicht zur Theorie. Offensichtlich wurde weniger gespart (was angesichts der Alterung verständlich ist), andererseits sind die Zinsen dennoch gefallen. Wir wissen, dass die Unternehmen in Japan in dem Zeitraum deutlich gespart haben und der Staat sich massiv verschuldet hat. In Summe dürfte sich so die Ersparnis Japans nicht groß verändert haben. Es war und ist eine Bilanzrezession.

Quelle: FvS

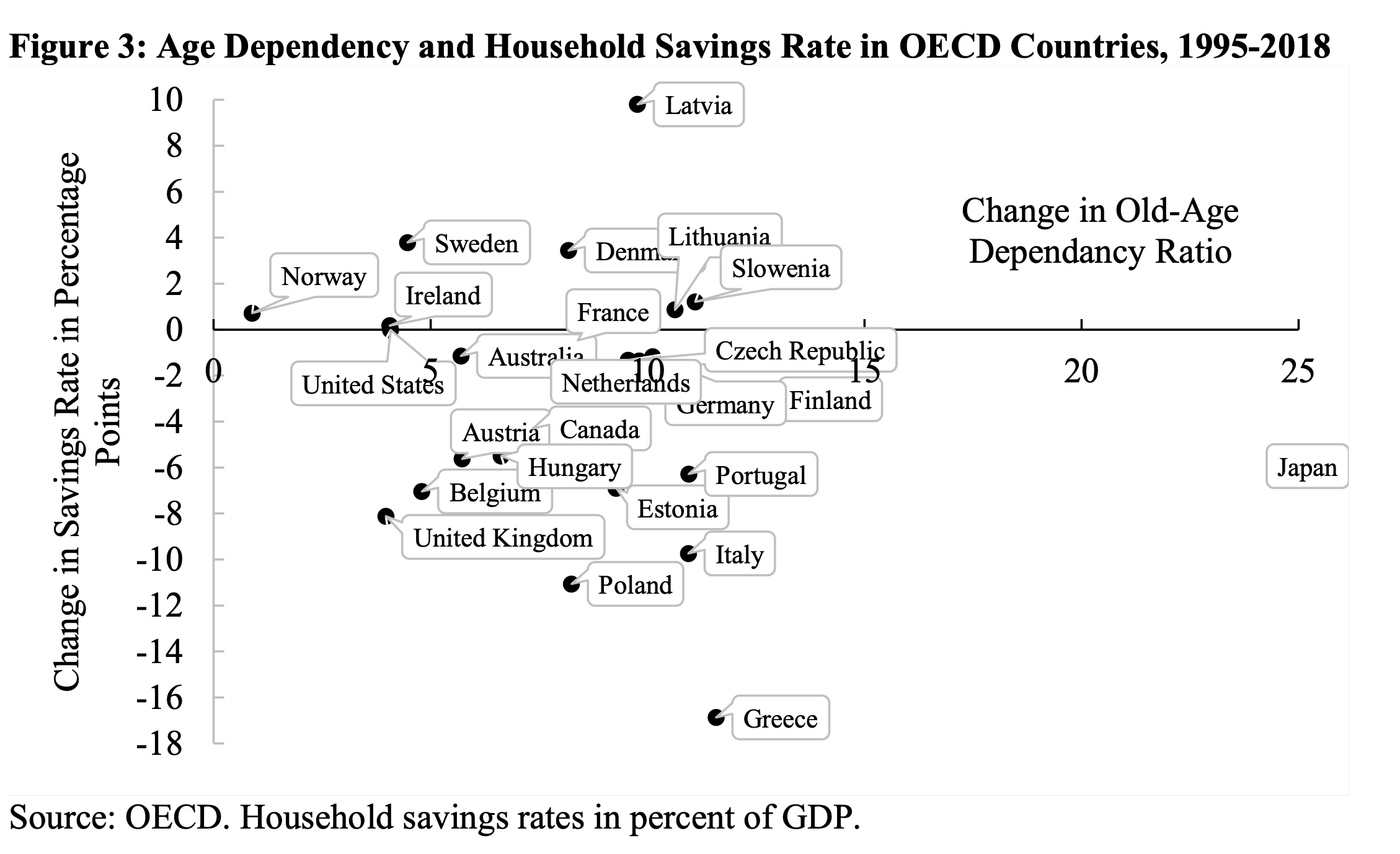

- “Also, for a broader sample of OECD countries, there is no robust evidence for a correlation of ageing societies and growing household savings rates. Figure 3 shows for the OECD countries on the x-axis the change in the old-age dependency ratio since 1995, proxied by the old-age dependency ratio in 2018 minus the old-age dependency ratio in 1995. A positive value indicates an aging society. For all OECD countries in the sample the societies have aged based on this measure. Japan stands out as a particularly fast aging society. The y-axis shows the difference in the household savings rate between 2018 and 1995 in percentage points. A negative (positive) value indicates a declining (increasing) household savings rate since 1995. Based on this measure the majority of countries experienced a decline in the household savings rate. The aging-society-savings-glut hypothesis would imply a close positive relationship between the two indicators in form of an upward trending line moving from the south-western to the north-eastern part of the Figure 3. But there is no correlation at all.” – bto: Jetzt müsste man allerdings auf die gesamtwirtschaftliche Ersparnis blicken. Länder mit einem Handelsüberschuss würden nach der Hypothese zu viel sparen und nicht nur ihre Waren exportieren, sondern auch ihr Kapital und so zu mehr Angebot führen. Jetzt wissen wir aber, dass auch bei dieser Betrachtung die Frage offen ist, was zuerst da war: die zusätzliche Verschuldung in den Abnehmerländern oder die Exporte und in Folge das Kapitalangebot?

Quelle: FvS

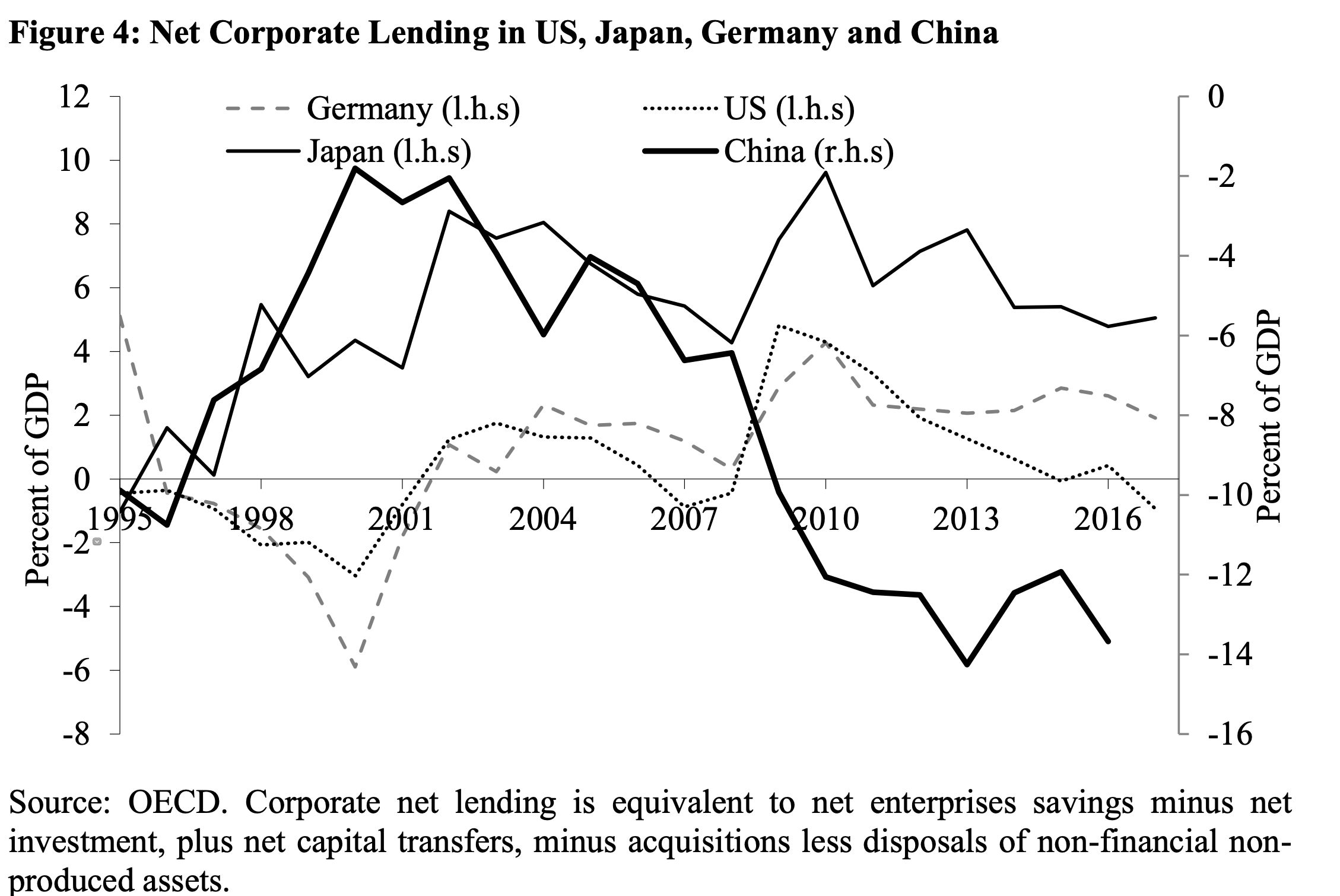

- “Instead of household savings rates, enterprise savings rates have increased in some industrialized countries such as Germany and Japan (Figure 4), due to three reasons. First, interest rate cuts reduced the financing costs of enterprises, which traditionally have been borrowers in capital markets. (…). Second, for the enterprises of export-oriented economies such as Japan and Germany depreciations of the domestic currencies caused by strong monetary expansions generated windfall profits. Third, fixed capital investment as percent of GDP tended to decline. This could be explained in the tradition of Hansen (1939) by slowing population growth (Summers 2014) and slowing technological innovation (Gordon 2012). More likely, however, enterprises anticipated slowing real wage growth because of relaxed interest rate constraints.” – bto: Diese Punkte sind nachvollziehbar. Zugleich erklärt es aber die Entwicklung der Unternehmensersparnisse, die in die Betrachtung einbezogen werden müssen.

Quelle: FvS

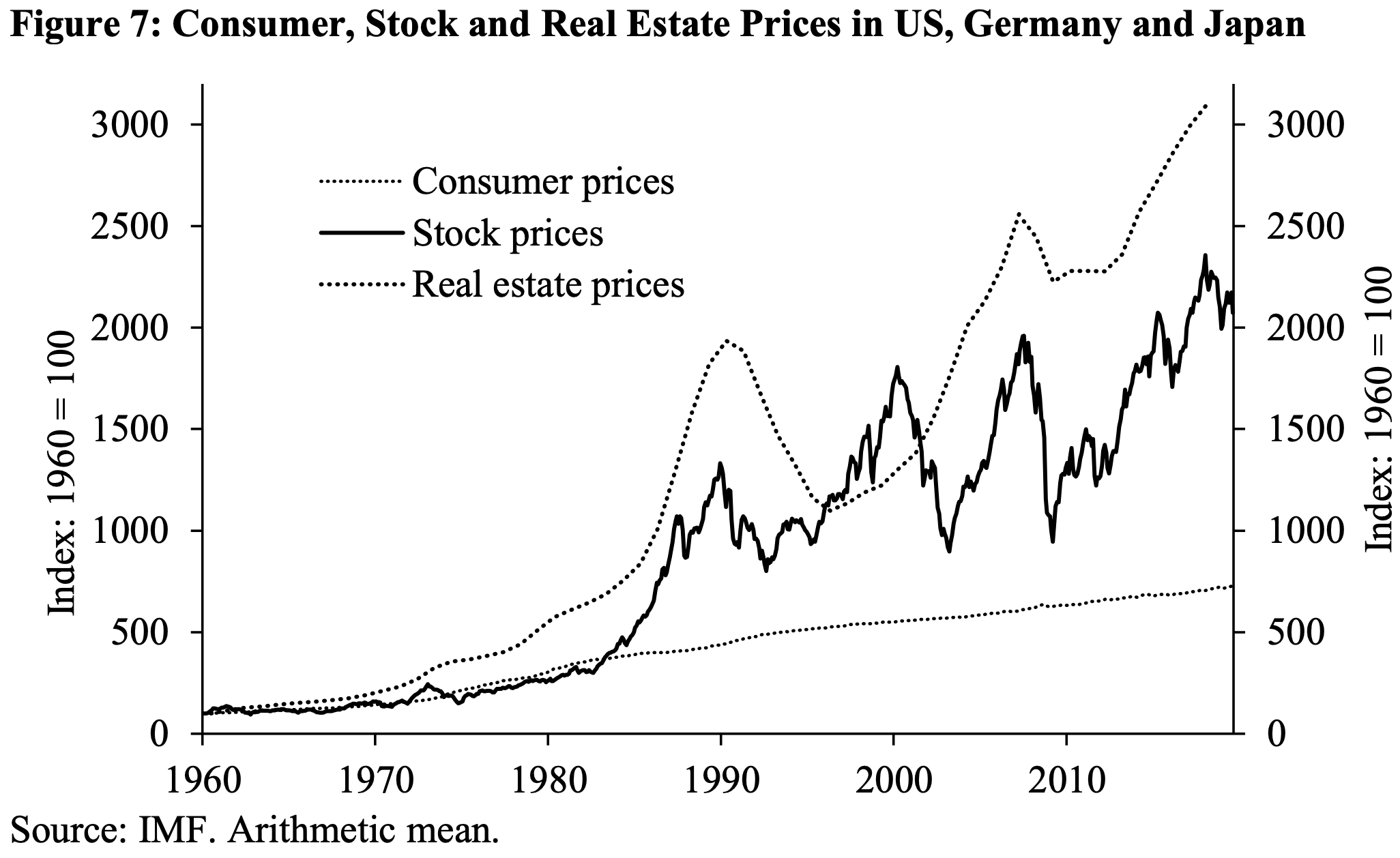

- Die Autoren zeigen dann, dass die Grenzproduktivität neuer Investitionen in den Kapitalstock in den letzten Jahrzehnten in der westlichen Welt stabil war, dass Geld der Notenbanken hier also keinen Effekt hatte. Umgekehrt ist die Entkoppelung der Finanzmärkte von der Realwirtschaft offensichtlich: “(…) the gradual decline of interest rates seems to have boosted real financial investment, with financial markets expanding. (…) Since the late 1980s, the arithmetic mean of stock and real estate prices in the US, Japan and Germany have – with fluctuations – increased strongly relative to consumer prices. With asset prices being inflated, the marginal productivity of financial investment seems to have declined as, for instance, indicated by increasing price-to-rent ratios in many real estate markets.” – bto: Das ist etwas, was Leute wie Piketty nicht verstehen wollen.

Quelle: FvS

- “When interest rates are pushed ever lower, possibly below the growth of real income, increasing levels of debt become sustainable. It becomes more attractive for enterprises to raise their return on equity through financial leverage than through non-financial investment aimed at increasing productivity. (…) Indeed, enterprises have raised their indebtedness substantially, in particular in the United States and China. In China, the additional credit has been used to build up a large capital stock. In Germany, since 2008 in particular large enterprises have strongly expanded the amount of outstanding bonds, encouraged by low interest rates and by corporate bond purchases of the European Central Bank. The additional funds have served different purposes, not least take-overs and acquisitions. (…) Mergers and acquisitions increased the market and pricing power, thereby creating monopolistic rents.” – bto: Es ist offensichtlich, dass Transaktionen wie der Kauf von Monsanto durch Bayer in einem normalen Zinsumfeld nicht stattgefunden hätten. Dass Unternehmen vor allem in den USA auf Financial Engineering setzen, ist ebenfalls offensichtlich.

- “If low interest rates induce enterprises to raise financial instead of fixed-capital investment and keep enterprises in business that would have been unprofitable otherwise, growth will decline (…) Schnabl (2015) shows for Japan that an ultra-loose monetary policy has continued to cause financial instability and sluggish growth. (…) persistently low interest rates have constituted a (…) ‘perverse’ incentive to keep low-return investments alive via a misallocation of credit to low return enterprises. (…) postponed restructuring in depressed industries (leads) to lower productivity growth, caused by what they call ‘zombie enterprises’. The distorted allocation of funds comes along with distortions in the financial sector, as the ultra-loose monetary policy reduces the incentive to clean bank balance sheets from bad loans. Furthermore, the margins of the traditional banking sector are squeezed (…).” – bto: was alles nicht nur offensichtlich und auch sehr einleuchtend ist.

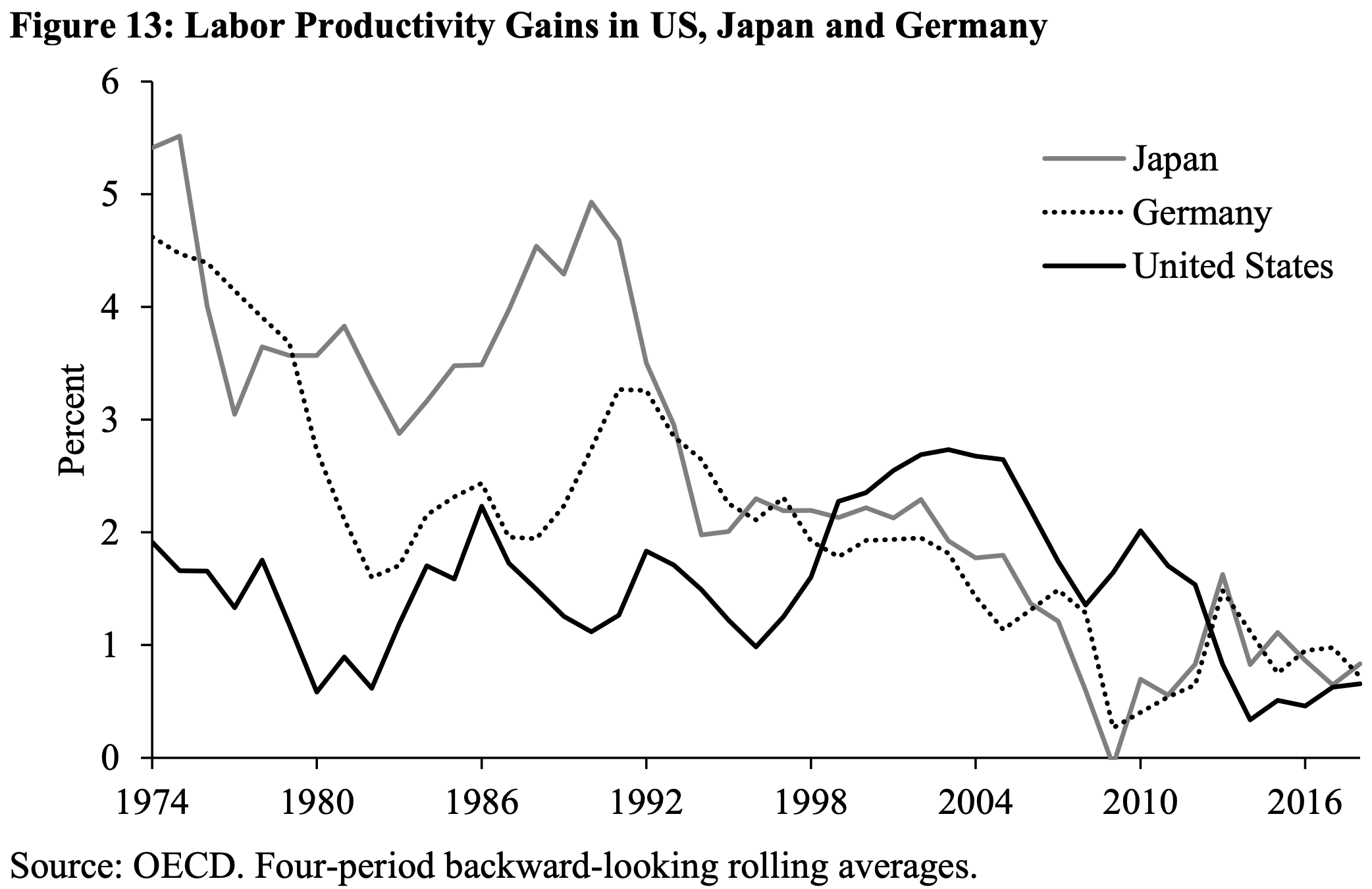

- Diese fehlende Bereinigung der Wirtschaft genügt aber nicht zur Rückkehr zu alten Wachstumsraten, zeigen die Autoren (was auch an der überbordenden Schuldenlast liegt, wie ich immer wieder erkläre). Deshalb gibt es einen anderen Effekt: “(…) increasingly loose monetary policies have prevented or even reduced unemployment by preserving distorted economic structures. Even more, in many countries, such as Japan and Germany, the number of employed increased as real incomes declined and more people entered the labor market. Therefore, the increasingly expansionary monetary policies of the large central banks have come along with declining labor productivity gains.” – bto: wobei man das ja durchaus als einen Erfolg ansehen könnte.

- “In neoclassical theory, labor productivity gains are the prerequisite for real wage increases. If the persistently loose monetary policies have reduced the incentives for banks and enterprises to innovate and create productivity gains, real wage levels are depressed. This effect is most pronounced in Japan, where real wages are trending downwards since 1998.” – bto: Ich finde es interessant, dass Japan sich in den letzten 20 Jahren dennoch besser geschlagen hat als Deutschland.

Kommen wir zum Fazit der Autoren:

- “We also find no empirical evidence for the savings glut and secular stagnation hypotheses. (…) the Austrian model incorporates a banking sector which either finances real fixed capital or financial investment. Interest rates have been depressed by a pro-active monetary policy when technological progress, closer trade ties, and overinvestment in China exerted downward pressure on prices. The global deflationary pressure originating from China can be linked to subsidized credit and overinvestment in China. Thus, expansionary monetary policies have boosted asset instead of goods prices and contributed to growing income inequality. Moreover, the Austrian view suggests that the depression of interest rates lowers productivity gains and trend GDP growth via quasi “soft budget constraints” for enterprises. It leads to an inefficient allocation of resources (…).” – bto: So kann man es zusammenfassen. Das große Problem ist allerdings, dass wir nun zwar wissen, wie wir diese Probleme bekommen haben, aber noch lange nicht, wie wir da wieder rauskommen.