So teuer wäre es, wenn die EU (oder Teile) zerfiele

Eine ausgesprochen interessante Frage werfen Professor Felbermayr und Kollegen in einer Studie auf: Was wäre, wenn die EU zerfiele? Zurzeit schaut die EU ja angesichts der Art und Weise, wie die Briten den Brexit managen und dank dem Einstieg in die Transfer- und Schuldenunion, stabilisiert aus. Aber, die Probleme gären weiter und es darf niemanden verwundern, wenn die nächste Krise nur einer Frage der Zeit ist. Nach Italien nehme ich nunmehr auch die Niederlande ganz nach oben auf meine Liste der potenziellen Austrittskandidaten.

- „Economists have regularly assessed the economic consequences of undoing Europe, or, conversely, the benefits of maintaining or deepening the EU. (…) By now, 27 countries form the EU (EU27). Nineteen of them are members of the European Monetary Union. Twenty-two EU members participate in the Schengen Agreement, where they are joined by some, but not all, members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Three of the four EFTA members, in turn, have joined the EU27 in forming the European Single Market. Moreover, the EU27 members’ budgets are linked through fiscal transfers, they form a Customs Union, and the EU as a legal entity has signed numerous regional trade agreements (RTAs) with countries all over the world. Therefore, a reversal of any or several steps of integration would affect European countries very differently.“ – bto: Vor allem wäre es sehr kompliziert.

- „A second source of complexity relates to the economic nature of integration. Over decades, deeply intertwined production processes in Europe and beyond have emerged, connecting firms from different sectors and countries. Hence, the economic effects of reversing an agreement would not be confined to its members, but would spill over to other countries along the demand and supply linkages that form the European and international production network.“ – bto: Auch das ist natürlich eine durchaus gewollte Komplexität der Integration, weil dies dem Anspruch nach Unumkehrbarkeit dient.

- „The estimated costs of a reversal of European integration are large, but vary greatly across agreements. Membership in the Single Market brings about 8 percentage points lower (non-tariff) trade costs in manufacturing and a 31 percentage points trade cost saving in services. Membership of the euro area yields trade cost savings of about 2 percentage points in goods and about 10 percentage points in services trade. The evaluation of the Schengen Agreement is more involved – how bilateral trade costs between two countries are affected depends on whether the transit countries between them are Schengen members (Felbermayr et al. 2016, 2018). Accounting for this complication, we find that abolishing border controls at one border reduces trade costs by 3 percentage points for goods and by 5 percentage points for services.” – bto: Wir sehen aber ganz klar, dass der Nutzen vor allem im gemeinsamen Markt liegt, nicht so sehr in der gemeinsamen Währung. Vor allem berücksichtigen die Einsparungen im Handel nicht die negative Wirkung des Euro auf die Wettbewerbsfähigkeit einzelner Staaten.

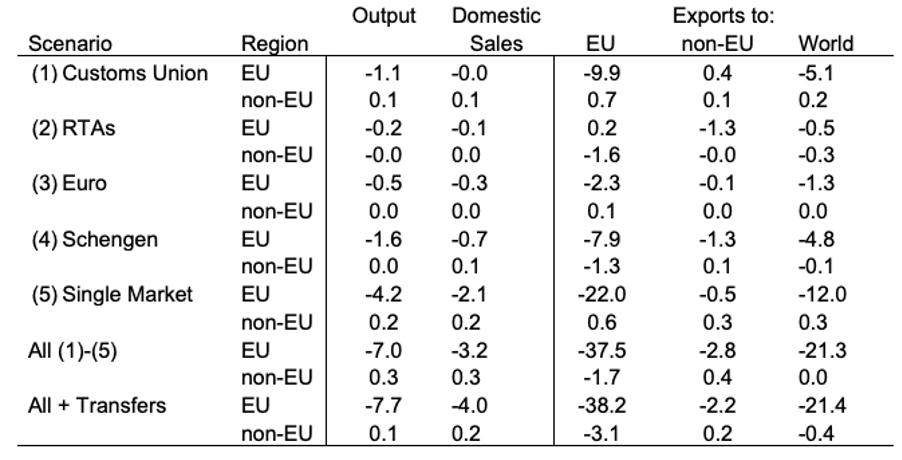

- „The simulated consequences of the trade cost hikes on trade and production in Europe are huge. Table 1 shows that a reversal of all agreements (Scenario ‘All (1)-(5)’) would slash intra-EU trade by almost 40%, compared to a 3% decline in exports to non-EU countries. Production and consumption in Europe are depressed; output falls by 7%, domestic sales (unaffected by trade cost increases!) drop by 3%. Higher border costs in Europe also destroy value chains. European value added in domestic sales drops even more than domestic sales as foreign sources become more competitive.“ – bto: Auch hier ist es interessant zu sehen, dass die Auflösung des Euro längst nicht so negative Folgen hätte.

Table 1 Aggregate agreement-specific and cumulative output and export effects

- „(…) the net effect of the sectoral adjustments resulting from undoing Europe is deindustrialisation: manufacturing in the EU loses about 0.2 percentage points of its share in total value added in the baseline simulation.” – bto: Das dürfte vor allem mit den Ecomomies of Scale zu tun haben.

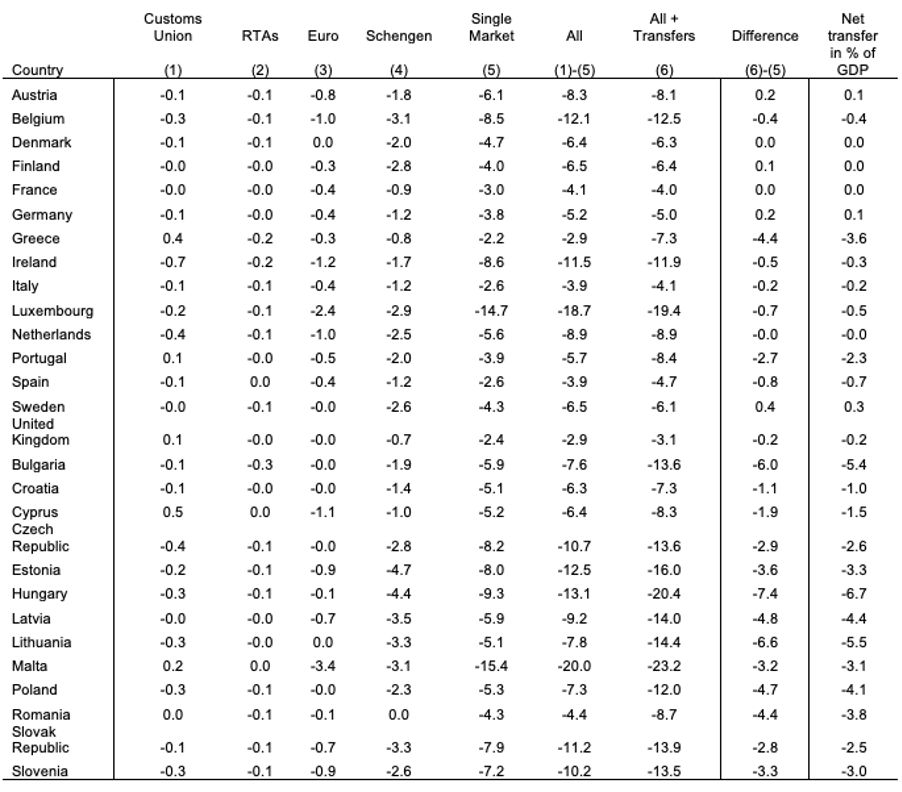

- „A complete breakdown of the EU would generate statistically significant real consumption losses for all EU members(see Table 3). Small open countries such as Malta, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Ireland would lose 20%, 19%, 12%, and 11%, respectively; larger countries such as Germany, France and Italy would lose 5%, 4%, and 4%, respectively. The least exposed EU country is Greece (-3%). Besides the small open economies, younger and poorer EU members from central and Eastern Europe have the most to lose. Being disproportionately reliant on demand from Europe and, compared for example to Germany, being less integrated in international production networks with global players such as China and the US, border barriers to intra-EU trade are hitting these states disproportionally hard.“ – bto: Irgendwie hätte man das auch erwartet. Gerade für kleinere Länder ist der Effekt größer.

Table 3 Agreement-specific and cumulative real consumption losses from reversing the European Integration (in %)

- „Putting an end to within-EU budget transfers creates further pain for the new EU members, slashing additional 7 percentage points (7 percentage points, 6 percentage points, 5 percentage points, 55 percentage points) off of real consumption in Hungary (Lithuania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Poland) (see Table 3, Column titled “Difference (6)-(5)”).“ – bto: Klar, Polen ist einer der größten Profiteure der EU.

- „Conversely, ending transfers reduces the losses from a reversal of the steps of integration for net contributors like Germany, Sweden, Austria and Finland and brings positive terms of trade effects. Yet, these positive effects are an order of magnitude smaller than the losses associated with re-establishing the border barriers in Europe.“ – bto: Auch das kann nicht so sehr überraschen.

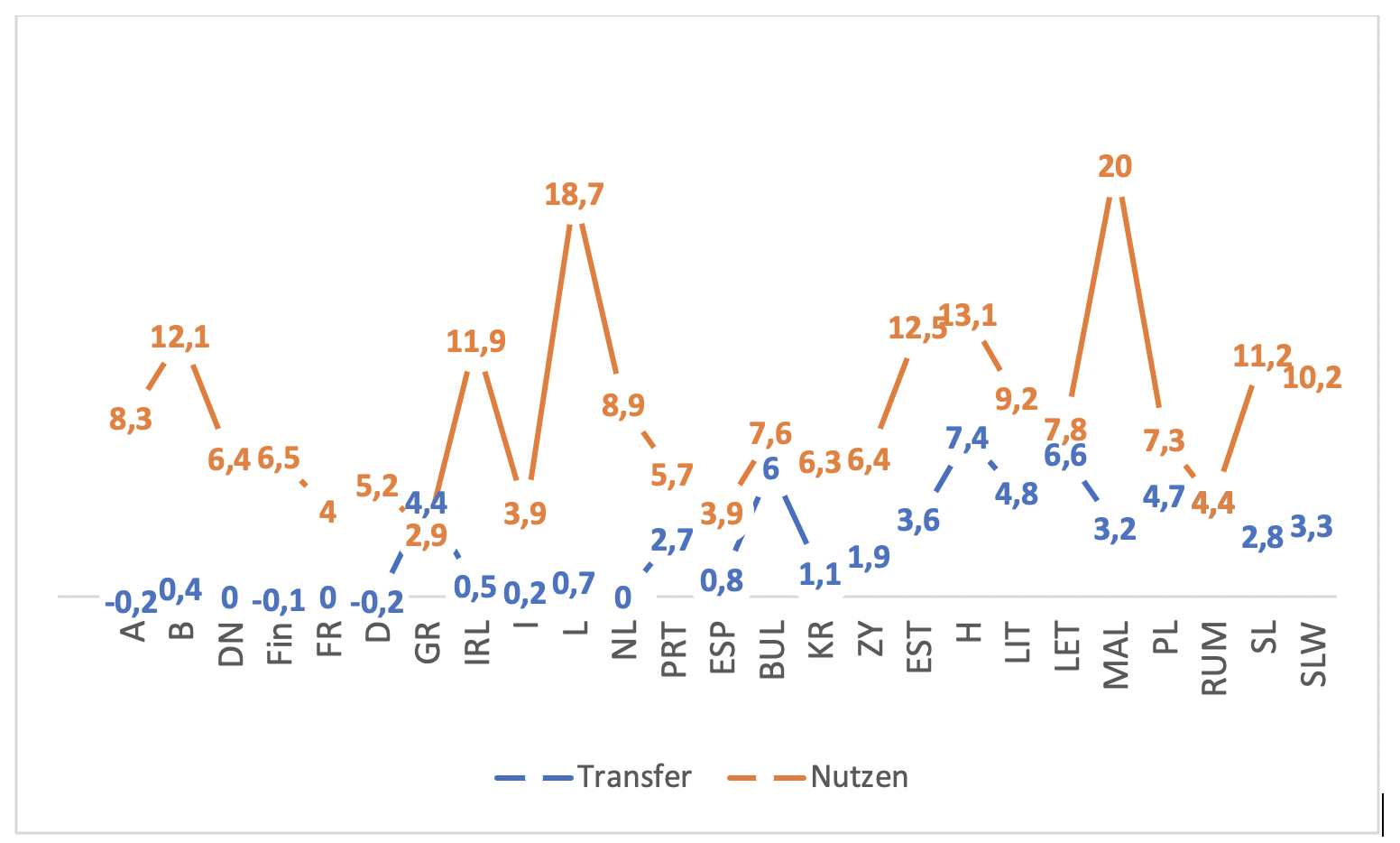

Man kann es aber auch anders darstellen:

Das liest sich dann so: Deutschland zahlt netto ein, deshalb ein negativer Wert von 0,2. Umgekehrt haben wir einen Nutzen aus dem Binnenmarkt etc., der sich in einem Wohlstandsgewinn von 5,2 Prozent gegenüber Situation ohne Binnenmarkt etc. niederschlägt. Meine These wäre dann, dass es in jenen Ländern, wo der Nutzen relativ zum eigenen Beitrag gering ist, die Bereitschaft zum Ausscheiden im Zuge von politischen und wirtschaftlichen Problemen am größten wäre. Italien sticht hier neben Spanien heraus. Großbritannien hatte gemäß diesen Daten den geringsten Nutzen aus dem Binnenmarkt.

Auffällig auch: Der Binnenmarkt ist entscheidend, nicht der Euro.

→ voxeu.org:”Complex Europe: Quantifying the cost of disintegration”, 6. September 2020