Sieben Fakten über Italien, die nichts ändern

Ich hatte das Vergnügen, in dieser Woche mit Philipp Heimberger über Italien zu diskutieren. Die angedachte Rollenverteilung war klar. Ich sollte der uninformierte deutsche Nationalist sein, der Vorurteile über Italien verbreitet und keine Ahnung hat. Meinem Gegenpart, Ökonom am Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) and am Institute for Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (Johannes Kepler University Linz), kam die Rolle zu, mich und das Publikum aufzuklären.

Eine Zusammenfassung des Gesprächs bringe ich am kommenden Sonntag (20. Juni 2021) in meinem Podcast.

Das Problem bei der Diskussion ist, dass es zwei verschiedene Diskussionen sind: Da ist zum einen die Frage, wie gut die italienische Wirtschaft dasteht und ob es wirklich die „faulen Italiener“ sind und zum anderen die Frage, ob es richtig ist, Transfers zu leisten und ob Letztere etwas in Italien bewirken können. Die letzten Aspekte stehen für mich im Vordergrund, die Antwort auf die erste Frage spielt dabei nur eine nachgeordnete Rolle. Denn die grundlegenden Probleme Italiens sind so massiv, dass man sie mit Geld nicht lösen kann.

Doch schauen wir uns zunächst die „sieben Fakten“ an:

„Italy is the second largest producer of industrial goods in the EU, has been running export surpluses over recent years and has often adhered more strictly to the European Union’s fiscal rulebook than Germany, Austria or the Netherlands.“ – bto: bekannt. Aber unzureichend als Begründung, um Geld nach Italien zu überweisen. Schauen wir sie uns dennoch an:

1. Italy is living below its means

- „‘Italy is living beyond its means!’ This omnipresent claim is readily supported by pointing to Italy’s public debt, which amounts to 135 per cent of its economic output. Yet this means only that the public sector is highly indebted—it says nothing about the Italian economy as a whole.“ – bto: Hier wird nebenher etwas ganz Wichtiges gesagt: Es ist ein Staatsschuldenproblem. Und es gibt noch viele weitere Probleme, wie ich später zeigen werde.

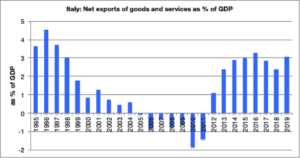

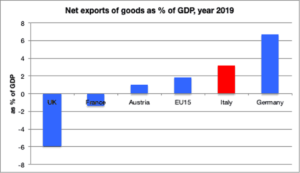

- „A country lives beyond its means if it imports significantly more goods and services than it exports over the long term. A country that exports as much as it imports is not however living beyond its means, as production and consumption are in line. Indeed, Italy has been recording export surpluses since 2012. (…) The Italian economy therefore consumes less than it produces—it lives below its means.“ – bto: Auch das stimmt und trifft bekanntlich ebenfalls auf Deutschland zu. Wenn man genauer hinschaut, ist es nicht nur zu wenig Konsum, sondern vor allem sind es zu wenig Investitionen im Land. Auch leider eine Parallele zu Deutschland.

Quelle: Heimberger

2. Private debt is not a problem in Italy

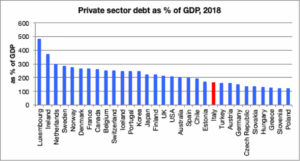

Auch das ist Lesern von bto seit Langem bekannt. Die Schulden der Italiener sind sehr gering und liegen deutlich unter den Schulden der privaten Haushalte hierzulande. Heimberger zeigt dazu diese Darstellung:

Quelle: OECD, Heimberger

3. Public debt is high because of errors made 40 years ago

Sodann zeigt Heimberger auf, dass die hohe Staatsverschuldung das Problem falscher Politik vor Jahrzehnten gewesen ist. Das ist übrigens immer so. Hohe Schulden müssen per Definition die Folge früherer Defizite sein.

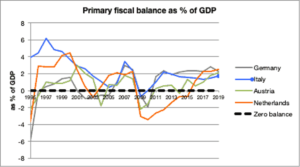

- “(…) the mistakes that were made 40 years ago took place in an international environment of increasing interest rates. Since then, the Italian state has been carrying a heavy interest-rate backpack. If we exclude the burden of interest rates, however, the Italian state has been consistently running budget surpluses since 1992 (with the exception of the crisis year 2009).“ – bto: In der Tat hat Italien in den Konvergenz-Jahren zum Euro nicht genug getan, um den Haushalt wirklich zu stabilisieren. Der Zinsrückgang hat den Anpassungsdruck damals gesenkt. Eine weitere Parallele zu heute.

- „Even Germany, Austria and the Netherlands have recorded a comparable positive ‘primary’ budget surplus less frequently than Italy. The Italian state has not been as ‘profligate’ as is often claimed: it has consistently collected more in taxes than it has spent.“ – bto: was ebenfalls Lesern von bto wohlbekannt ist und vermutlich eine der Ursachen für das geringe Wirtschaftswachstum, was wiederum die Schuldenproblematik verschärft.

Quelle: OECD, Heimberger

4. Italy’s economy has suffered since joining the euro

- „In 2000, Italy’s average standard of living was virtually equal to that of Germany (98.6 per cent of its GDP per head). But after the introduction of the euro in 1999, the country fell behind the UK (in 2002) and France (in 2005) once more. By 2019, Italian per capita income was more than 20 per cent below that of Germany.“ – bto: was sicherlich damit zu tun hat, dass die Italiener nicht wie früher regelmäßig abwerten konnten. Sie haben an Wettbewerbsfähigkeit verloren und deshalb würde ich die Rückkehr von Handelsüberschüssen nicht als Indikator für Wettbewerbsfähigkeit sehen, sondern als Folge von Verzicht. Das ist nicht positiv.

- „Whether Italy can ever regain economic momentum within the eurozone will to a large extent depend on the willingness of Germany and ‘frugal’ countries such as Austria and the Netherlands to reform the euro architecture—especially where European fiscal rules are concerned.“ – bto: Das sehe ich anders. Die Probleme lasen sich nicht mit mehr Schulden und mehr Transfers lösen. Doch dazu morgen mehr.

5. Italy has carried out many market-liberal reforms

- „In 2015, the OECD assessed Italy’s ‘reform efforts’ as significantly stronger than those of Germany and France. The Dutch economist Servaas Storm takes a similar line. In an in-depth study he finds that Italy has adhered much more closely to the EU’s policy rulebook than Germany or France.“ – bto: Das stimmt und zeigt nur, dass wir noch mehr Probleme haben: Frankreich mit deutlich höherer Gesamtverschuldung und wir mit dem Kaputtsparen des Landes.

- “In 2014, Matteo Renzi’s government reduced workers’ protection against dismissal, extending labour-market deregulation which began in the 1990s. According to Storm, making the labour market more ‘flexible’—also in line with European requirements led to a sharp increase in fixed-term contracts, pushed back the trade unions and contributed to a decline in real wages, compared with Germany and France. ‘Structural reforms’ from the market-liberal playbook not only reduced inflation in the 1990s. They may also have contributed to reducing unemployment, as the rate in Italy was lower than in Germany and France when the financial crisis hit in 2008. But cheap labour also diminished incentives for Italian companies to make labour-saving investments, key to the productivity improvements which are the basis for long-term growth and rising incomes. Both austerity and market-liberal reforms have inhibited Italy’s productivity growth and, on balance, may have brought more macroeconomic damage than benefits.“ – bto: Es ist eine schlüssige Argumentation, was nicht bedeutet, dass sie stimmt. Wir haben es weltweit mit einem Rückgang der Produktivitätsfortschritte zu tun. Es ist eine mathematische Zwangsläufigkeit, dass die Produktivität gedämpft wird, wenn man Menschen mit geringer Qualifikation in den Arbeitsmarkt integrieren möchte. Dann hat man zunächst weniger Produktivität, aber eben auch weniger Arbeitslose. Über Zeit sollten dann die Löhne wieder steigen – in Deutschland am überproportionalen Anstieg der Löhne im Niedriglohnbereich vor Corona zu beobachten.

6. Italy is the second most important industrial country in the EU

- „(…) Italy is still the second most important EU location, behind Germany, for industrial production, mainly due to the economic structures in the northern regions. And it ranks third in exports of goods, just behind France, leading on mechanical engineering, vehicle construction and pharmaceutical products. This order is almost identical to Germany’s export structure, and the OECD classifies the industries concerned as ‘medium-high-tech’ to ‘high-tech’.“ – bto: Das stimmt, aber die Basis erodiert (wie auch bei uns).

Quelle: AMECO, Heimberger

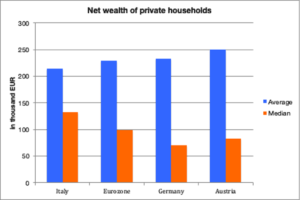

7. Italians are not richer than Germans or Austrians

Kommen wir zu dem Argument, wegen dem ich zum Streitgespräch eingeladen wurde: die Frage, ob die ärmeren Deutschen die reicheren Italiener retten sollen (wie ich immer wieder geschrieben habe) oder ob das falsch ist:

- „Finally, one often hears the argument that Italians are wealthier than, for instance, Germans or Austrians and should therefore pay for their investments themselves. The median Italian household, that located exactly between the richer upper half and the poorer lower half of the population, is indeed wealthier than the corresponding German or Austrian household. But the average Italian household—obtained by dividing the total net wealth by the total number of households—is clearly less wealthy than in Germany or Austria.“ – bto: Das stimmt, spring aber zu kurz, wie ich morgen an dieser Stelle erklären werde.

Quelle: EZB, Heimberger

Die Frage ist, wenn man den Punkten 1 bis 6 zustimmt (7 besprechen wir morgen), was ich tue (warum sollte ich auch Fakten widersprechen, in Details mag man anderer Ansicht sein), was ist die Schlussfolgerung?

Für Heimberger ist sie:

- Reform der EU-Fiskalregeln – Klartext: Wir machen mehr Schulden bzw. lassen mehr Schulden zu.

- Aktive Rolle der EZB – Klartext: EZB garantiert Italien und Co. dauerhaft tiefe Zinsen und einen geringen Spread über deutschen Anleihen.

- Transfers: Er betont zwar, dass er den Wiederaufbaufonds für einmalig hält (tue ich nicht, ich halte ihn für einen großen Fehler der deutschen Politik), wünscht sich aber ein dauerhaftes Instrument.

- Europäische Industriepolitik: Italien (und einige andere, denke ich) soll durch eine europäische Industriepolitik schneller wachsen (und damit wohl auch die Schulden besser verkraften).

Ich halte das für eine Illusion.

→ socialeurope.eu: „Seven ‘surprising’ facts about the Italian economy“, 25. Juni 2020