Rekordbörse bedeutet nichts anderes als geringe künftige Erträge

Die Kapitalisierung der Weltbörsen liegt bei über 100 Prozent des BIP, nach Warren Buffet ein klares Blasensignal. Ob er deshalb Gold kauft? Nun, ich denke, in einer Welt wie der heutigen, wo man mit einer Monetarisierung der Extraklasse rechnen muss, kann man schlecht sagen, wo das noch hinführt. Daran ändert auch die kleine Korrektur an der NASDAQ in der letzten Woche nichts.

Wenn man wie John Hussman noch an die Rückkehr zu fundamentalen Daten glaubt, kann man sich in der Tat keine so großen Hoffnungen auf Erträge machen. Denn – wie kürzlich am Beispiel der Duration gesehen – je tiefer die Zinsen, desto höher muss der Preis sein. Vor allem von Dingen, deren Wert sich erst am Ende des Betrachtungszeitraums ergibt.

Doch kommen wir zu Hussman und seiner – altertümlichen? – Fundamentalanalyse:

- “Given any set of future cash flows, the higher the price you pay today, the lower the long-term rate of return you can expect on your investment. Nothing about this relies on mean-reversion. It’s just arithmetic. For any given set of expected future cash flows, knowing the price immediately tells you the expected return. Knowing the expected return immediately tells you the price. It’s just arithmetic. You don’t need to ‘adjust’ these calculations for the level of interest rates. Now, once you calculate the expected investment return, you can certainly compare it with the level of interest rates, but the idea that valuations have to be ‘corrected’ for interest rates reflects a misunderstanding of basic finance.” – bto: Deshalb ist der Preisanstieg nichts anderes als ein vorgezogener Ertrag. Wobei man natürlich schon sagen kann, dass man angesichts des tiefen Zinsniveaus Cashflows höher bewertet. Das bedeutet aber: “well, future stock returns are likely to be dismal, but dismal returns on stocks are justified because you’re going to get dismal returns on bonds too”. – bto: woran man wenig ändern kann. Was sind die Alternativen? Cash? Wohl zum Teil ja.

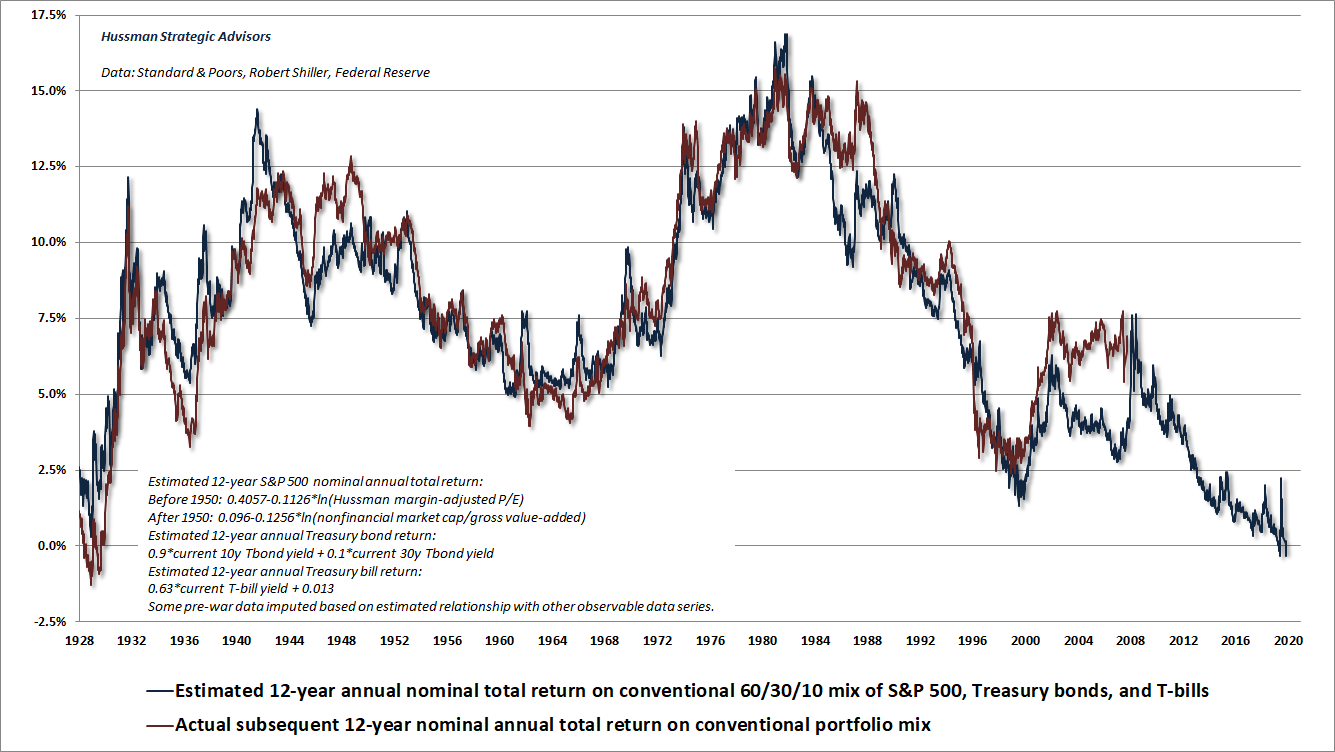

- “Worse, by our estimates, the likely 10-year total return of the S&P 500 from current valuations is about -1.4% annually. The chart below illustrates the situation that passive investors face here. The blue line shows our estimate of 12-year prospective returns on a conventional passive asset mix invested 60% in the S&P 500, 30% in Treasury bonds, and 10% in Treasury bills. The red line shows actual subsequent 12-year returns on this portfolio mix.” – bto: Das Modell hat zumindest die Vergangenheit gut abgebildet.

Quelle: Hussman

- “Our most reliable valuation measures now match or exceed 2000 levels. Over the completion of the current market cycle, I expect that the entire S&P 500 total return since 2000 will be wiped out. Specifically, I continue to expect the S&P 500 to lose about two-thirds of its value. Even a 50% market retreat would bring valuations only to levels matching the 2002 low, which was the highest valuation level ever observed at the completion of a market cycle.” – bto: Jetzt muss man festhalten, dass Hussman schon seit Jahren warnt – und er hat bisher nicht Recht bekommen.

- Dann kommt er mit einem Beispiel, das auch ich verwende: “Suppose you buy the piece of paper for $68, and overnight, investors suddenly become willing to pay $100 for it. Well, instead of your 4% return occurring over 10 years, as you wait for your $100 payment, you’ll instead accrue an unexpectedly large return all at once. Of course, since the price is now $100, you’ll ultimately get nothing additional for continuing to hold. The sudden spike in the price has compressed your entire long-term expected return into an overnight windfall. Simultaneously, the new, higher valuation of $100 ensures that your future return will be zero.” – bto: So ist es und da hilft es auch nicht, wenn man wie bto-Leser Herr Tischer in einem Kommentar auf die tiefere Inflation verweist. Das würde nur dann stimmen, wenn die Zinsen nicht unter die Rate des nominalen Wachstums gedrückt würden.

- “Even during the bubble period, there has been no breakdown of the inverse relationship between valuations and long-term market returns. We don’t know what market returns will be over the coming decade, but the arrow shows where present valuations stand. Investors should be fully prepared for a decade of zero stock market returns.” – bto: Das leuchtet mir ein

Quelle: Hussman

- “(…) our most reliable market valuation measures presently match the 1929 and 2000 extremes, and our gauge of internal uniformity is also unfavorable. Present conditions are characterized by an extreme ‘overvalued, overbought, overbullish’ syndrome, which would notbe enough encourage a bearish outlook if our measures of internals were favorable, but certainly adds to our concerns at present.” – bto: Was uns allerdings wenig hilft, denn bekanntlich kann das lange andauern.

- “Current valuations are essentially triple those that would be consistent with historically run-of-the-mill stock market returns of about 10% annually. This already implies that probable long-term investment returns will be dismal for passive investors. Notice also that this doesn’t assume any mean reversion at all. If there is mean-reversion in valuations, as there has been during every market cycle in history, including those since 2000, the outcome will be catastrophic for investors over the completion of this cycle, because it implies a nearly two-thirds loss in the S&P 500 simply to reach pedestrian historical norms.” – bto: Auf diese Rückkehr zum langjährigen Durchschnitt warten wir allerdings ebenfalls schon seit Jahren.

Womit wir bei der Rolle der Notenbanken wären:

- “In the face of zero-interest rate policy and other Fed interventions, historically reliable ‘overvalued, overbought, overbullish’ conditions failed to impose any useful ‘limit’ to investor speculation. (…) So don’t expect us to ‘fight’ Fed-induced speculation in periods when our measures of market internals become uniformly favorable. Some conditions may be sufficiently extreme to warrant a neutral outlook, but in general, when our measures of market internals are favorable, our market outlook – at least near term – is likely to be constructive (…).” – bto: Solange andere Indikatoren wie die Risikobereitschaft der Investoren nicht zu optimistisch werden, muss man angesichts der Geldpolitik mittanzen – und zwar ohne Pause.

- “We know very well from 2000-2002, 2007-2009, late-2018, early-2020, and indeed all of market history, that U.S. stocks have lost value, sometimes profoundly, in periods when the Fed has been easing but divergent market internals have indicated risk-aversion among investors. There’s a simple reason why easy money fails in those environments. When investors are risk-averse, low interest liquidity is a desirable asset, not an inferior one. So creating more of the stuff doesn’t encourage speculation.” – bto: Das setzt voraus, dass die Maßnahmen der Fed als nicht mehr nutzbringend angesehen werden oder andere Faktoren, wie beispielsweise die politischen Rahmenbedingungen, ungünstiger werden.

- “The Fed’s brazen step into illegal actions has certainly encouraged a market rebound from the March lows. (…) Recently, the Fed has started to discuss the possibility of ‘yield curve control,’ which would essentially amount capping interest rates – a form of price control where the Fed would commit to buying Treasury bonds to keep their yields from rising. Jerome Powell has mentioned ‘short term’ yield control, but with short-term yields at the lowest levels in history, the Fed’s tendency toward mission creep would likely target longer-term Treasury yields as well. Fortunately or unfortunately, we already have a good idea of how such a policy would end. It’s worth examining the outcome when the Fed tried the same thing in 1942, in an attempt to enable the enormous deficits of World War II. By 1948, inflation shot to 10% and a recession ensued, despite a 2.5% cap on long-term Treasury yields. As the Fed’s balance sheet expanded, the interest rate caps became untenable, and the Fed was ultimately forced to abandon the cap in 1951 amid a second inflation surge toward 10%.” – bto: Und die darf ja bekanntlich nicht kommen, weil sie nicht kommen kann und die Notenbanken heute stärker gegensteuern. Oder nicht?

- Übrigens: Die illegalen Aktionen der Fed sind der Kauf von Unternehmensanleihen auch zweifelhafter Qualität, was sie laut Gesetz nicht darf. “The Fed has announced the intention to ‘leverage’ the funds approved by Congress with additional money creation, in an amount ranging between 3-10 times what Congress actually allocated, in order to buy unsecured corporate bonds from private investors. Aside from the violations of law involved here, and the shift of private risk onto the public balance sheet, it’s important to understand is that the financial effect is to amplify speculation and the issuance of low-grade debt.” – bto: So ist es. Es wird Spekulation belohnt und gefördert, nicht der Realwirtschaft geholfen.

- “(…) the only way to sustain elevated valuations is to sustain depressed future investment returns. You have to understand that propping up low-grade securities vastly increases their issuance to unsuspecting investors. You have to understand that the Fed is literally printing and allocating purchasing power in return for unbacked assets that may prove to be worth far less. (…) Overvalued markets can only be protected by destroying future investment prospects and by misallocating capital.” – bto: Das bedeutet genau das Gegenteil für die Realwirtschaft.