Produktivität, Automatisierung, Protektionismus und Migration

Immer wieder ranken sich Diskussionen bei bto um ähnliche Themenkreise:

- geringe Produktivitätszuwächse in Folge zu geringer Investitionen und daraus abgeleitet das Szenario der ökonomischen Eiszeit mit geringen Wachstumsraten;

- die Notwendigkeit – angesichts geringer Produktivitätszuwächse und demografischer Entwicklung – die sich abzeichnende Welle der Automatisierung nicht als Gefahr, sondern als Chance zu begreifen;

- die zunehmende Gefahr von Protektionismus im verzweifelten Versuch einen nicht umkehrbaren Trend der Arbeitsplatzverluste durch Globalisierung und Automatisierung doch umzukehren;

- die irrige Annahme, Migration könnte in diesem Umfeld die Probleme verringern. Das Gegenteil ist der Fall. Sie erhöht das Heer der Arbeits- und Perspektivlosen.

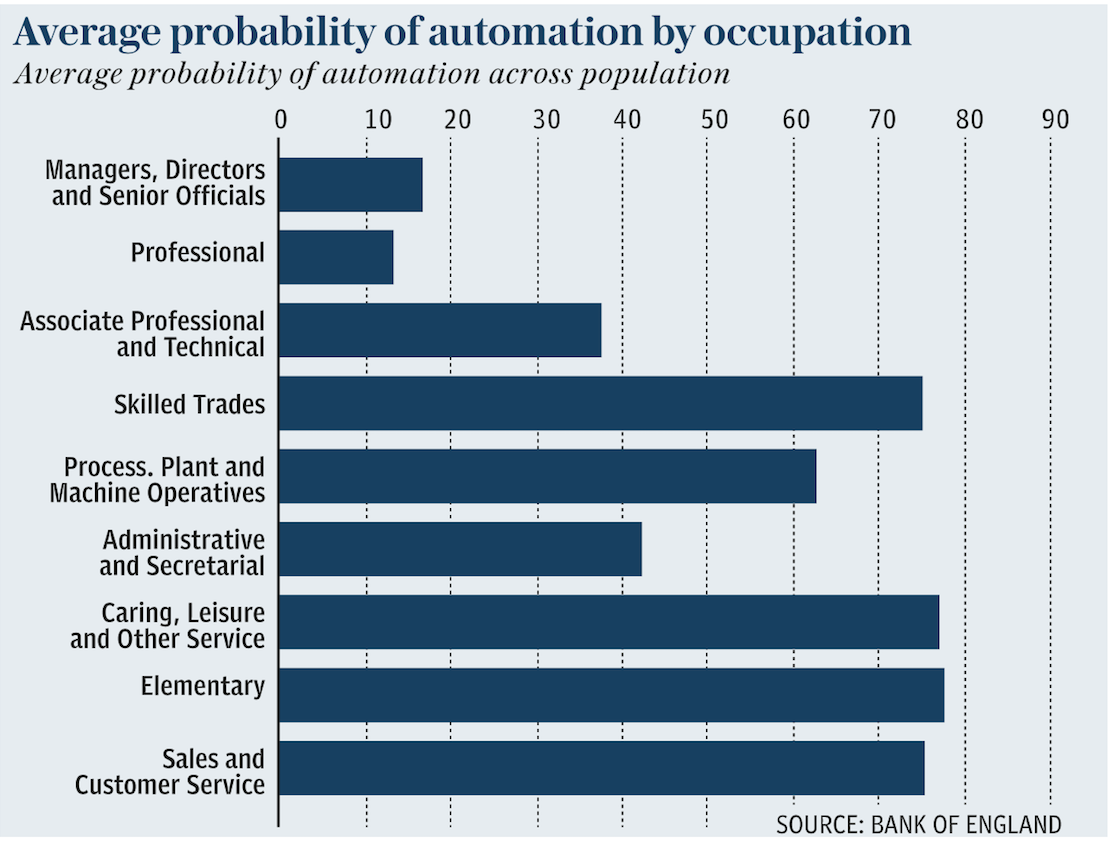

Dies alles gehört zusammen, wie die FT in einer kleinen Serie verdeutlicht hat. Bevor ich auf die Kernaussagen eingehe, eine grafische Zusammenfassung der Herausforderung:

Quelle: The Telegraph

Doch nun zu den Überlegungen der FT:

Die Roboter kommen

- “The more you look, the more opportunities you find for greater productivity through automation or simply better work practices. The possibilities range from the frivolous, such as the pizza delivery robots to be tried out in Germany and the Netherlands, to the exotic, such as the rise of investment funds that let computer algorithms rather than human analysts pick which securities they hold.” – bto: was wir auch der obigen Darstellung entnehmen können.

- “That raises the questions of how automation fits in with stalling economy-wide productivity, and the vexed debate on how much automation, rather than trade and globalisation, was to blame for the loss of well-paid blue-collar jobs in recent decades.” – bto: Das ist wirklich die Frage. Wenn es solche Innovationen gibt, weshalb steigt dann die Produktivität nicht. Das kann natürlich am Messverfahren liegen, wie hier diskutiert: → Kommt der große Produktivitätsschub?

Zeigt sich nicht in der Produktivität

- “It was Robert Solow who first quipped — in 1987! — that ‚you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics‘.” – bto: Und das ist auch so geblieben, abgesehen von einem Boom in den 1990ern.

- “The Solow paradox was to a certain degree resolved by the late 1990s productivity boom in the US — though that did not last very long, and what growth has been seen in manufacturing productivity has predominantly been down to more efficient production of computing equipment itself, rather than in the use of information technology to produce other things.” – bto: Das wusste ich noch nicht. Es war also die Effizienz in der Herstellung der IT-Infrastruktur und nicht in der Gesamtwirtschaft.

- “Perceptions can deceive: behind all the anecdotal observations of a new machine age dawning, the reality is that, for now, most advanced economies are failing to invest in new capital. IMF (…) point to a lack of capital as the main cause of slow productivity. It can be read in conjunction with a new McKinsey report that synthesises recent evidence (and adds some of its own) covering similar ground. The overall finding is that in the US in particular but in advanced countries in general, investment in capital has been exceedingly weak in the past decade. McKinsey finds that in the US, capital intensity — measured as capital services available to workers per hour worked — has fallen since 2010.” – bto: Die Unternehmen haben es zum Teil auch nicht nötig zu investieren, wegen der oligopolistischen Strukturen in einigen Märkten und des billigen Gelds. Finanzoptimierung bringt mehr.

(Noch) investieren die Firmen zu wenig

- “Productivity-enhancing machines will not enhance productivity if they are not actually given to workers to use, which is what low investment and stagnant (or worse) capital intensity indicate. (…)the IMF blames weak capital growth for not just poor labour productivity but also poor ‚total factor productivity‘.” – bto: Und da wäre die Frage, ob wir nicht doch eine Bereinigungskrise brauchen, bevor es richtig losgeht.

- “McKinsey finds (…) the sectors that are the best at digitising their work processes, and also often the most productive, are not the biggest; and conversely, the sectors making up the largest shares of economic activity typically lag behind in digitisation.” – bto: Das deckt sich mit meiner Erfahrung. Könnte aber gut sein, dass es dann wie bei einem Tsunami funktioniert.

- “To the extent this simple explanation is correct, it should be seen as cause for optimism, not pessimism. Investment can be boosted with better policy — a combination of more intensive demand stimulus with a policy framework that gives companies a sense of predictability.” – bto: also, für Optimismus mit Blick auf die Produktivität.

Wer hat die Jobs vernichtet?

- “Who stole the jobs — was it robots or foreigners? Or less tendentiously, was the falling number of manufacturing jobs in rich countries caused by trade liberalisation or by automation and other productivity-enhancing technological change?” – bto: Das verstärkt sich gegenseitig ist das Fazit der FT.

- “(…) both trade and automation play a role. But second and more importantly, that the two cannot be neatly separated — automation-driven productivity growth and attendant job loss may be both an ultimately unavoidable part of economic change and be accelerated by trade liberalisation. Rich economies with highly-skilled labour forces are well placed to respond to greater trade by specialising in higher-value added products — just those where automation can do the most to increase productivity.” – bto: Das bedeutet aber auch, dass die Menschen umso besser ausgebildet sein müssen, um überhaupt mitzuhalten!

- Danach geht es um die Frage, ob Protektionismus hilft. Klare, wenig überraschende Antwort – nein: “The best responses, rather, involve domestic policies. Those will have to be policies that harness the benefits of automation, not ones that try to stop it (such as a robot tax).” – bto: Nein, das würde nur sicherstellen, dass das Land, dass diese einführt, noch schneller den Bach runtergeht.

Bedingungsloses Grundeinkommen als Antwort

- “In the area of radical reform to achieve this, there are two rivals currently receiving a lot of attention. One is universal basic income (UBI) — an unconditional income from the state to all, regardless of job or other status and intended to replace much of the welfare state’s existing income support.” – bto: zur Erinnerung: Das schreibt die FT. Ich bin übrigens auch ein Anhänger und habe dies in Der Billionen-Schuldenbombe erstmals erläutert, damals noch aus dem Blick der Staatseffizienz.

- Dann zur Abgrenzung von der Idee, für alle Menschen Jobs im öffentlichen Sektor zu schaffen: “Over the long term, however, the fact that UBI leaves job creation to the private sector means it can meet the goals of the job guarantee proponents better than the job guarantee itself. It is important to recognise that one function of UBI is to create demand for jobs that serve the UBI recipients themselves — because that’s what they will be spending their money on.” – bto: Das kann ich nachvollziehen, denke aber, wir brauchen beides. Auf keinen Fall sollten zu viele Leute ohne Aufgabe zu Hause rumsitzen, da dies ebenfalls Sprengstoff darstellt. Das führt mich dann auch zu dem Thema Migration. Letztere bedeutet in der heutigen Welt nichts anderes, als die Anzahl der Transferempfänger zu erhöhen.

→ FT (Anmeldung erforderlich): “Money can buy you work”, 6. April 2017