Private und staatliche Schulden und Finanzkrisen

Steve Keen fasst in einem Beitrag nochmals zusammen, wie private und öffentliche Schulden wirken:

- “(…) private debt causes crises, and public debt, to some extent, ends them. But conventional economic theory gets this completely wrong, by ignoring private debt, while seeing government debt as a problem rather than a solution. The conventional economic argument is firstly, that private debt simply transfers spending power from one private person to another—the debtor has more money to spend when money is borrowed, the creditor has more to spend when debt is repaid. In the aggregate, this cancels out: the borrower’s spending power rises when debt is rising and falls when it is falling, but the lender’s spending power goes in the opposite direction. They claim, therefore, that changes in the level of private debt have very little impact on the economy.” – bto: Das ist unzweifelhaft falsch. Wir wissen ja, dass Kredite neues Geld darstellen.

- “On the other hand, they see government debt as ‘crowding out’ the private sector, by competing with private borrowers for the available stock of ‘loanable funds’, and thus driving up the interest rate—the price of borrowed money. Excessive government deficits add to the demand for money, drive up interest rates, and therefore reduce private investment, and hence the rate of economic growth.” – bto: Auch dies stimmt nicht, wie wir wissen. Auch hier erhöhen die Schulden das Geldangebot.

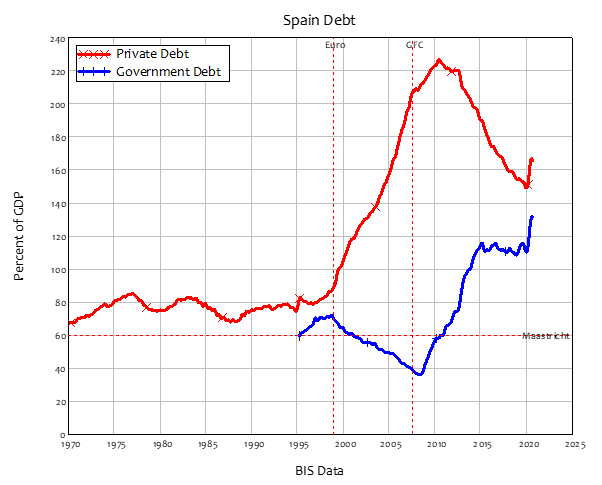

- In diesem Chart sieht man sehr schön die Entwicklung in Spanien ab der Euroeinführung bis zur Krise. Die Staatsschulden stiegen erst, als der von Privatschulden getriebene Boom am Ende war:

Quelle: Steve Keen

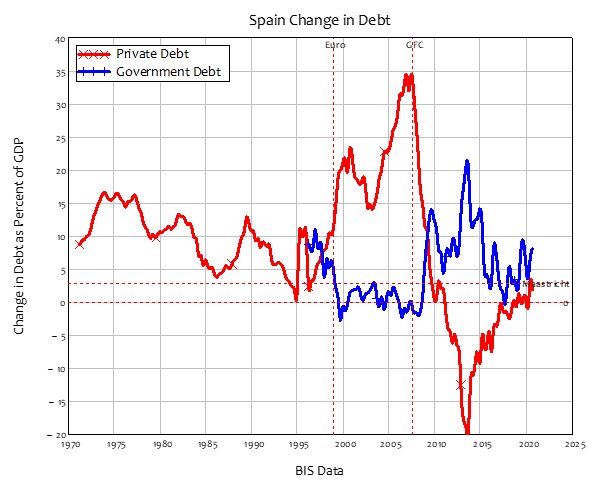

- “Looking at the annual change in debt, the same picture emerges: while Spain congratulated itself for staying below the Maastricht target of government deficits being below 3% of GDP, credit (the annual change in private debt) rose from zero before the Euro began to as much as 35% of GDP during the boom. It then fell to as low as minus 20% of GDP in 2014.” – bto: Das ist der Kern des Problems. Wir haben mit dem Euro eine Verschuldungsmaschine geschaffen und die Schulden sind vor allem unproduktiv verwendet worden.

Quelle: Steve Keen

Quelle: Steve Keen

- “If conventional economics were correct, then there shouldn’t have been a crisis at all in 2007—and this is exactly what mainstream economists said at the time. (…) Since there was a crisis there must be something wrong with conventional economic thought. And there is, because it asserts that the actual details of money don’t matter to macroeconomics—that the macroeconomy can best be understood by ignoring money, and treating the economy as a barter system.With this belief, they have never built a framework for analysing how money is actually created. Instead, they developed a ‘supply and demand’ model of lending called ‘Loanable Funds’, where savers lend more when interest rates are high, and borrowers demand more when interest rates are low, and the market sets both the quantity lent and the interest rate.” – bto: Das ist der Kern der sehr berechtigten Kritik.

- “In 2014, the Bank of England categorically declared that this model was wrong: banks do not take in deposits from some customers and lend them out to others, but instead, ‘Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits’. This means that private lending doesn’t cancel out, as the mainstream still believes. Instead, rising bank debt creates new money and causes a rising amount of spending, while falling bank debt destroys money and contracts spending. This is obvious in the data: when credit is positive and rising, unemployment falls; when credit is negative and falling, unemployment rises.” – bto: Deshalb ist es heute auch so bedeutsam, dass die Geldmenge wächst, denn damit kommt es zu wirklicher Nachfrage und vermutlich auch höherer Inflation.

- “(…) rather than bank loans shuffling existing money between savers and borrowers, bank lending increases the money supply; and rather than government deficits adding to the demand for money, they add to the supply of money. (…) To create money therefore, you have to do something that adds to bank deposits. Both bank lending and government deficits qualify, but in different ways.” – bto: Deshalb kommt es so sehr darauf an, wofür das Geld verwendet wird.

- “Since people borrow in order to spend, rising private debt stimulates aggregate demand and asset prices, making the economy—and the government—look great to conventional eyes. The economy booms, unemployment falls, and booming tax receipts make the government look like it is responsible by running a surplus. But if the rate of growth of private debt—otherwise known as credit—turns negative, then everything unravels. The economy goes into a recession, unemployment rises, asset prices fall, and government debt increases—and if it didn’t, the recession would be far deeper.” – bto: Das stimmt. Zugleich sehen wir aber, dass die Produktivität neu geschaffener Schulden immer mehr abnimmt, was zu höherer Verschuldung und damit Schuldenquoten zwingt. Dies bedingt dann immer tiefere Zinsen. Dennoch ist ein Prozess, der nicht ewig weitergehen kann.

- “(…) the mainstream is also wrong about government deficits and government debt. Rather than deficits meaning that the government has to take money away from the private sector—which is what the mainstream thinks the government does when it sells bonds to cover a deficit—the deficit creates money by increasing the bank deposits of the private sector.” – bto: Dies ist die Logik der doppelten Buchführung. Die Frage ist jedoch auch hier, wie sich die Geldmenge relativ zum Produktionspotenzial entwickelt und wofür das Geld verwendet wird.

- “So all the arguments they make have it back the front: deficits crowd in private spending and investment by increasing the supply of money and, if anything, they drive down the interest rate, rather than driving it up.” – bto: einfach deshalb, weil die Geldmenge entsprechend zunimmt. Geld wird nicht knapper, sondern freier verfügbar.

- “The bonds that Treasury issues to cover the deficit are also sold in the first instance to the banking sector, and this lets them swap the excess Reserves that the deficit creates with Bonds. Bonds earn interest income, while normally Reserves don’t. So it’s a sensible thing for banks to buy them when Treasury offers them for sale: they get to swap a non-tradeable and non-income earning asset (Reserves) for a tradeable and income-earning asset (Bonds). That’s why bond issues by governments of countries that have their own currencies are always oversubscribed.” – bto: weil die Regierung zuvor das Geld geschaffen hat, mit dem die Banken die Anleihen kaufen konnten.

- “Unfortunately, governments belonging to the European Union gave up both these differences when they created the Euro. Draghi’s ‘whatever it takes’, and the EU ignoring its own silly rules on the maximum levels of government debt and deficits during the crisis, meant that the ECB reduced the severity of the crisis to some degree, but nowhere near as much as did America, which ran huge deficits because it wasn’t subject to the EU’s silly rules.” – bto: Wir haben bisher keine Lösung gefunden, wie wir damit umgehen wollen. Vor allem hat unterschiedliche Geldschaffung der Mitgliedsländer eine Umverteilungswirkung.

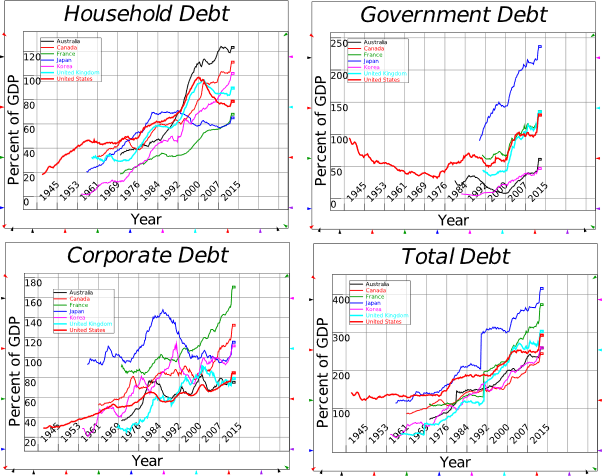

- “(…) private debt is so high now, in virtually all Western countries, that credit—the annual change in debt—is likely to be small, while people will spend the money they currently have slowly because they want to hang onto whatever money they currently have to service their existing debts. The result is what I call “credit stagnation” rather than a crisis.” – bto: Hier denke ich aber, dass die Klimapolitik die beste Basis bietet, um zu einem echten Kreditwachstum zu kommen. Siehe auch Russel Napier am letzten Montag.

Quelle: Steve Keen