McKinsey fasst zusammen: (fast) alles schlimmer als vor zehn Jahren

Meine Ex-Kollegen haben das Thema Finanz- und Schuldenkrise schon vor Jahren ad acta gelegt. Einer der Gründe für meine Entscheidung, BCG vor fünf Jahren zu verlassen. Wie die Zeit vergeht! Hatte BCG in den Krisenjahren mit der Analyse der Ereignisse und der richtigen Prognose der kommenden Trends die Diskussion geprägt – ich durfte da meinen Beitrag leisten – so ist das Thema heute fest mit McKinsey verbunden, die nicht nur die Disziplin hatten, an dem Thema dranzubleiben, sondern – wenn auch verspätet – auf die unangenehmen Szenarien hinzuweisen:

→ „McKinsey sieht die Eiszeit“

→ McKinsey für Vermögensabgabe und Monetarisierung

Seither wird regelmäßig aktualisiert, wie sich die Schuldensituation entwickelt. Dabei machen die Kollegen nichts anderes, als die öffentlich verfügbaren Daten optisch ansprechender zusammenzufassen, was allerdings zu dem gewünschten Effekt der medialen Präsenz führt. Kaum ein Artikel zum Thema, der nicht die McKinsey-Darstellungen nutzt. Zurecht.

Hier nun das letzte Update:

Immer mehr Schulden

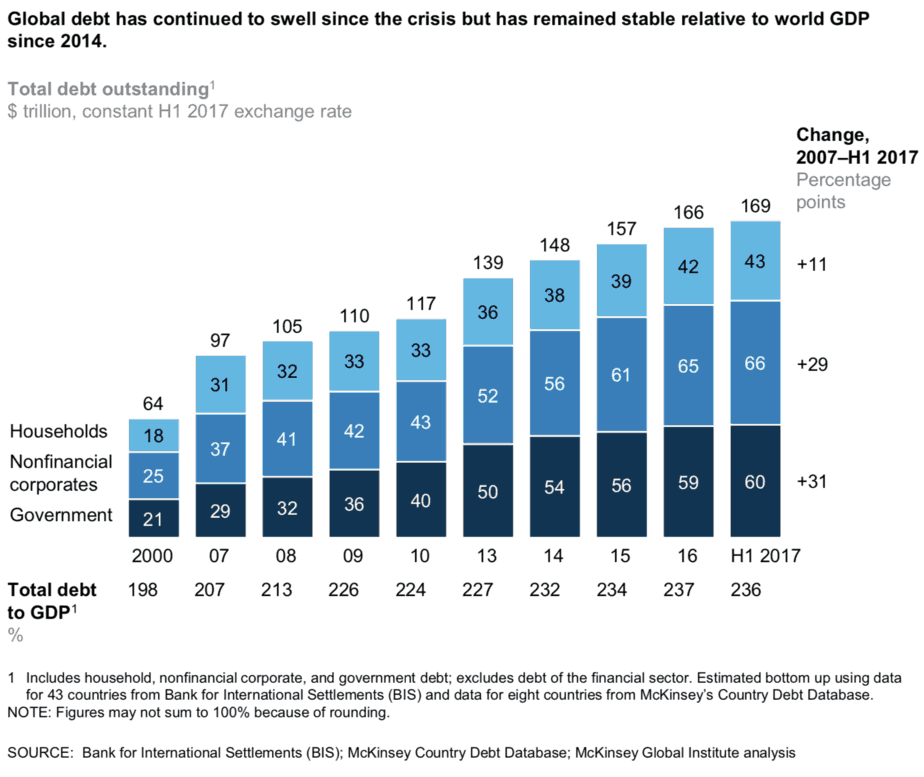

- “As the Great Recession receded, many expected to see a wave of deleveraging. But it never came. Confounding expectations, the combined global debt of governments, nonfinancial corporations, and households has grown by $72 trillion since the end of 2007 (Exhibit 1). The increase is smaller but still pronounced when measured relative to GDP.” – bto: Das wissen wir alles, aber die Abbildung ist schön.

- “Governments in advanced economies have borrowed heavily, as have nonfinancial companies around the world. China alone accounts for more than one-third of global debt growth since the crisis. Its total debt has increased by more than five times over the past decade to reach $29.6 trillion by mid-2017. Its debt has gone from 145 percent of GDP in 2007, in line with other developing countries, to 256 percent in 2017. This puts China’s debt on a par with that of advanced economies.” – bto: mit den hier kürzlich (erneut) diskutierten Risiken.

Quelle: McKinsey

Staatsschulden steigen

- “Consistent with history, a debt crisis that began in the private sector shifted to governments in the aftermath. From 2008 to mid-2017, global government debt more than doubled, reaching $60 trillion. Among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, government debt now exceeds annual GDP in Japan, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Rumblings of potential sovereign defaults and anti-EU political movements have periodically strained the eurozone. High levels of government debt have set the stage for pitched battles over spending priorities well into the future.” – bto: womit wir eine globale Großkoalition von Inflationisten und Bankrotteuren haben, weshalb es selten dämlich ist, dass wir hier so viel sparen.

Schwellenländer gefährdet

- “In emerging economies, growing sovereign debt reflects the sheer scale of the investment needed to industrialize and urbanize, (…) Countries including Argentina, Ghana, Indonesia, Pakistan, Turkey, and Ukraine have recently come under pressure as the combination of large debts in foreign currencies and weakening local currencies becomes harder to sustain.” – bto: auch hier besprochen. Sich in einer fremden Währung zu verschulden, ist immer hochgefährlich.

- “The International Monetary Fund assesses that about 40 percent of low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa are already in debt distress or at high risk of slipping into it.” – bto: Allerdings spielen die für Weltwirtschaft und -finanzsystem keine große Rolle.

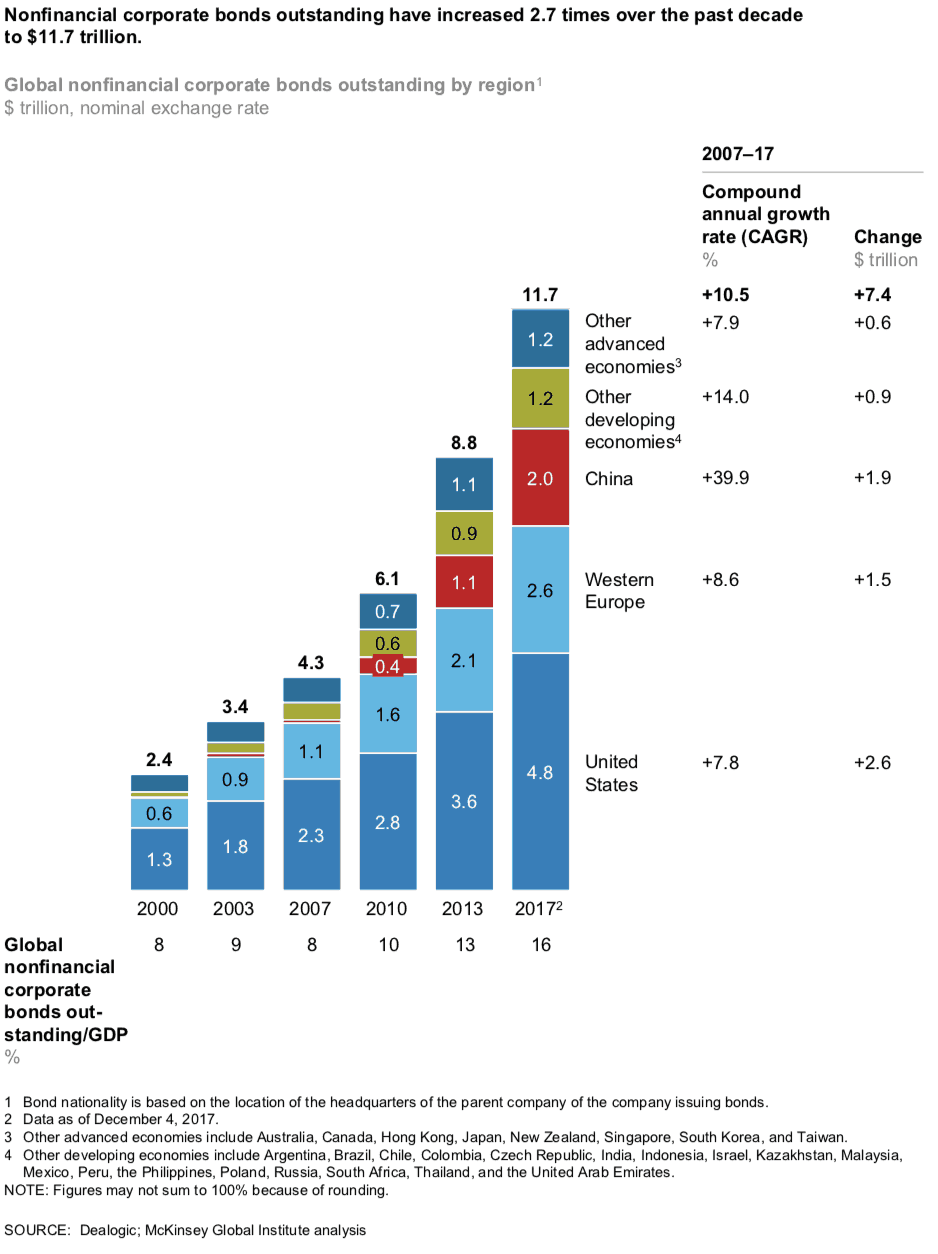

Unternehmensschulden als Hauptrisiko

- “Global nonfinancial corporate debt, including bonds and loans, has more than doubled over the past decade to hit $66 trillion in mid-2017. This nearly matches the increase in government debt over the same period. (…) This poses a potential risk, particularly when that debt is in foreign currencies. Turkey’s corporate debt has doubled in the past ten years, with many loans denominated in US dollars. Chile and Vietnam have also seen large increases in corporate borrowing.” – bto: Und damit ist es ein Problem- und Krisenherd. Egal, was man nun dazu sagen möchte, es ist ein Thema, sobald Zinsen steigen oder die Wirtschaft sich abschwächt.

- “China has been the biggest driver of this growth. From 2007 to 2017, Chinese companies added $15 trillion in debt. At 163 percent of GDP, China now has one of the highest corporate-debt ratios in the world. We have estimated that roughly a third of China’s corporate debt is related to the booming construction and real-estate sectors.” – bto: Klartext – unproduktiv und vermutlich zu einem guten Teil faul.

- “Companies in advanced economies have borrowed more as well. (…) corporate lending from banks has been nearly flat since the crisis, while corporate bond issuance has soared. The diversification of corporate funding should improve financial stability, and it reflects deepening capital markets around the world. Nonbank lenders, including private-equity funds and hedge funds, have also become major sources of credit as banks have repaired their balance sheets.” – bto: Da wundere ich mich allerdings sehr. Weil gleichzeitig die Banken weniger Eigenhandel machen dürfen, sind diese Märkte sehr illiquide. Hinzu kommt der hohe Anteil der “leveraged loans”, siehe Diskussion bei bto letzte Woche. Das ist dann schon ein erhebliches Risiko und das Gegenteil einer “improved financial stability”…

Quelle: McKinsey

Haushalte (versuchen zu) sparen

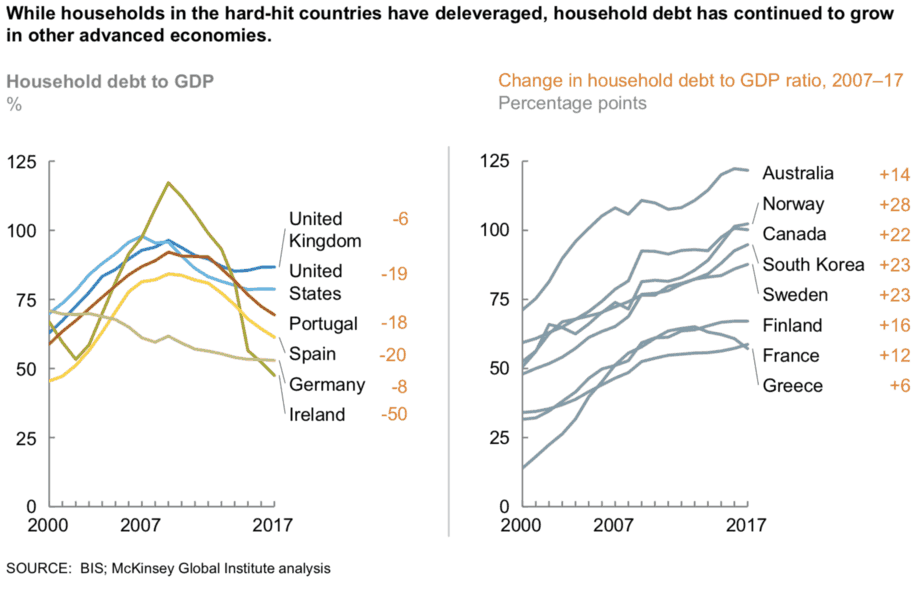

Die privaten Haushalte – Quelle der letzten Krise wegen zu hoher Schulden vor allem für Immobilien – versuchen derweil zu sparen:

- “Having slogged through a painful period of repayment, foreclosures, and tighter standards for new lending, US households have reduced their debt by 19 percentage points of GDP over the past decade (Exhibit 4). But the homeownership rate has dropped from its 2007 high of 68 percent to 64 percent in 2018 — and while mortgage debt has remained relatively flat, student debt and auto loans are up sharply.” – bto: vier Prozentpunkte in zehn Jahren!!! Das war es? Klarer kann man nicht machen, dass es eben nicht möglich ist, zu deleveragen. Erklärt übrigens auch Donald Trump als POTUS.

- “Household debt is similarly down in the European countries at the core of the crisis. Irish households saw the most dramatic growth in debt but also the most dramatic decline as a share of GDP. (…) Spain’s household debt has been lowered by 21 percentage points of GDP from its peak in 2009—a drop achieved through repayments and sharp cuts in new lending. In the United Kingdom, household debt has drifted downward by just nine percentage points of GDP over the same period.” – bto: Ja, es gab einen Abbau. Die Staatsschulden stiegen derweil in diesen Ländern deutlich.

- “In countries such as Australia, Canada, South Korea, and Switzerland, household debt is now substantially higher than it was prior to the crisis. (…) Today, household debt as a share of GDP is higher in Canada than it was in the United States in 2007.” – bto: was wiederum vor allem mit Immobilien zu tun hat. Klare Folge unserer Geldordnung.

Quelle: McKinsey

Gesündere Banken?

Danach erklärt McKinsey, weshalb das Bankensystem heute gesünder ist. Der Teil der Analyse, den ich gerne glauben will, wo ich mir aber nicht so sicher bin. Ich denke, wir haben noch mehr Probleme – gerade in Europa –, als wir wahrhaben wollen.

- “The Tier 1 capital ratio has risen from less than 4 percent on average for US and European banks in 2007 to more than 15 percent in 2017. The largest systemically important financial institutions must hold an additional capital buffer, and all banks now hold a minimum amount of liquid assets.” – bto: Diese Definition ist für Außenstehende schwer erklärlich. Wenn wir an die Non-Performing Loans in Italien und die zweifelhafte Qualität der Stresstest in Europa denken, so ist das nicht beruhigend.

- “In the past decade, most of the largest global banks have reduced the scale and scope of their trading activities (including proprietary trading for their own accounts), thereby lessening exposure to risk.” – bto: Aber dafür haben wir weniger liquide Märkte, was die Stabilität eher gefährdet als sichert.

- “But many banks based in advanced economies have not found profitable new business models in an era of ultra-low interest rates and new regulatory regimes. Return on equity (ROE) for banks in advanced economies has fallen by more than half since the crisis. The pressure has been greatest for European banks. Their average ROE over the past five years stood at 4.4 percent, compared with 7.9 percent for US banks.” – bto: was zum einen an der Geldpolitik liegt, zum anderen an der ungelösten Schuldenproblematik in der Eurozone.

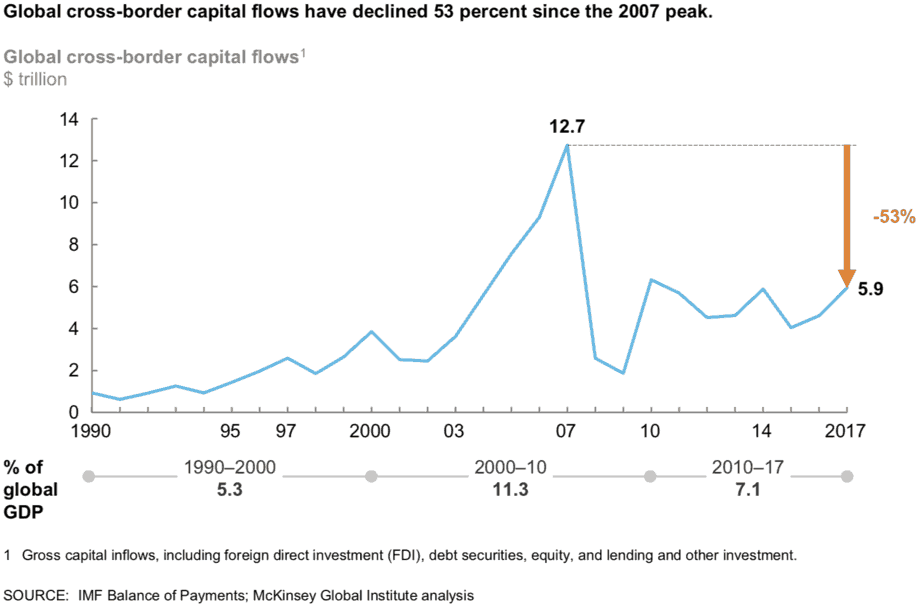

- “One of the biggest changes in the financial landscape is sharply curtailed international activity. Simply put, with less money flowing across borders, the risk of a 2008-style crisis ricocheting around the world has been reduced. Since 2007, gross cross-border capital flows have fallen by half in absolute terms.” – bto: was übrigens auch die Target2-Problematik erklärt!

Quelle: McKinsey

- “Eurozone banks have led this retreat from international activity, becoming more local and less global. Their total foreign loans and other claims have dropped by $6.1 trillion, or 38 percent, since 2007 . Nearly half of the decline reflects reduced intra-eurozone borrowing (and especially interbank lending). Two-thirds of the assets of German banks, for instance, were outside of Germany in 2007, but that is now down to one-third.” – bto: Wie ich sagte, spiegelbildlich wuchsen die Target2-Forderungen der Bundesbank.

Die Risiken

McKinsey kommt damit zu dem vorsichtig optimistischen Schluss, dass das Finanzsystem stabiler sei. Andererseits weisen sie auch auf die Risiken hin:

Hohe Unternehmensschulden:

- “The growth of corporate debt in developing countries poses a risk, particularly as interest rates rise and when that debt is denominated in foreign currencies. (…) There has been notable growth in noninvestment-grade “junk” bonds. Even investment-grade quality has deteriorated. Of corporate bonds outstanding in the United States, 40 percent have BBB ratings, one notch above junk status. We calculate that one-quarter of corporate issuers in emerging markets are at risk of default today — and that share could rise to 40 percent if interest rates rise by 200 basis points.” – bto: Und das trifft immer sofort beides: die Finanzwelt und die Realwirtschaft.

- “Another development worth watching carefully is the strong growth of collateralized loan obligations. A cousin of the collateralized debt obligations that were common prior to the crisis, these vehicles use loans to companies with low credit ratings as collateral.” – bto: so ist es, siehe letzte Woche bei bto.

Immobilienblasen

- “Since the crisis, real-estate prices have soared to new heights in sought-after property markets, from San Francisco to Shanghai to Sydney. Unlike in 2007, however, these run-ups tend to be localized, and crashes are less likely to cause global collateral damage. But sky-high urban housing prices are contributing to other issues, including shortages of affordable housing options, strains on household budgets, reduced mobility, and growing inequality of wealth.” – bto: Ja, denke dennoch, dass Krisen in Kanada und Australien und dem einen oder anderen lokalen Markt ausstrahlen.

China – was sonst

- “While China is currently managing its debt burden, there are three areas to watch. First, roughly half of the debt of households, nonfinancial corporations, and government is associated, either directly or indirectly, with real estate. Second, local government financing vehicles have borrowed heavily to fund low-return infrastructure and social-housing projects. In 2016, 42 percent of bonds issued by local governments were to pay old debts. This year, one of these local vehicles missed a loan payment, signaling that the central government might not bail out profligate local governments. Third, around a quarter of outstanding debt in China is provided by an opaque ‚shadow‘ banking system.” – bto: gute Zusammenfassung.

Andere Risiken

- “The world is full of other unknowns. High-speed trading by algorithms can cause “flash crashes.”(…) Cryptocurrencies are growing in popularity, reaching bubble-like conditions in the case of Bitcoin, and their implications for monetary policy and financial stability is unclear. And looming over everything are heightened geopolitical tensions, with potential flash points now spanning the globe and nationalist movements questioning institutions, long-standing relationships, and the concept of free trade.” – bto: Auch hier kann man nur zustimmen.

Fazit: Zehn Jahre später sind wir bei nüchterner Betrachtung nicht weiter. Und das Thema ungelöste Krise der Eurozone klammert McKinsey auch aus. Klar, denn dafür haben auch die Kollegen keine machbare und schmerzfreie Lösung.