Liegt der Höhepunkt der Inflation hinter uns?

Am 8. Mai 2022 geht es – erneut – um die Geldpolitik in meinem Podcast. Zu Gast ist Professor Ottmar Issing, der erste Chefvolkswirt der EZB und ein wirklicher Kenner der Materie.

Zur Einstimmung einige Beiträge.

John Authers fasst bei Bloomberg den Stand der Inflationsdebatte zusammen:

- Zunächst der Hinweis, dass das Wachstum der Geldmenge bereits seit geraumer Zeit rückläufig ist: “After an extraordinary expansion in 2020, year-on-year changes in both the euro zone and the U.S. are back to normal ranges, though still toward the top. Extreme growth is over, and will continue to slow from here.” – bto: Und damit entfällt ein wesentlicher Treiber für höhere Inflation.

- “Chris Watling of Longview Economics Ltd. in London suggests that falling monetary aggregates in combination with rising rates mean that the steps to crush inflation have already been taken. For him the real question is: ‘Did Powell and the Fed have their `U.S. Treasury Accord’ moment earlier this year when they switched to a hawkish stance and started aggressively to bring money supply growth under control? And, with that, have they already been somewhat successful?’ His answer is yes, and he adds: ‘Typically, a central bank has two jobs: i) To control the money supply (and therefore inflation); and ii) to act as lender of last resort. The history (of wars, pandemics, and multiple monetary systems) shows that, if the central bank chooses to control inflation, it’s more than capable.’” – bto: Das ist angesichts der hohen Verschuldung und der Blasen im Finanzsystem ein schwieriger Weg, der durchaus zu einer Rezession führen kann.

- “In taking this view, Watling shows an unfashionable confidence in the ability of central banks to clean up their own mess, and more importantly he suggests that there is enduring truth in monetarism, famously summed up by Milton Friedman with the contention that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary issue. Money supply, more than anything else, in other words, drives prices.” – bto: Das denke ich auch, und es ist ein erhebliches Problem, dass die Notenbanken so überrascht waren, dass es zu Inflation kommt. Denn die Geldmenge ist so stark gestiegen, dass es zu Inflation kommen musste.

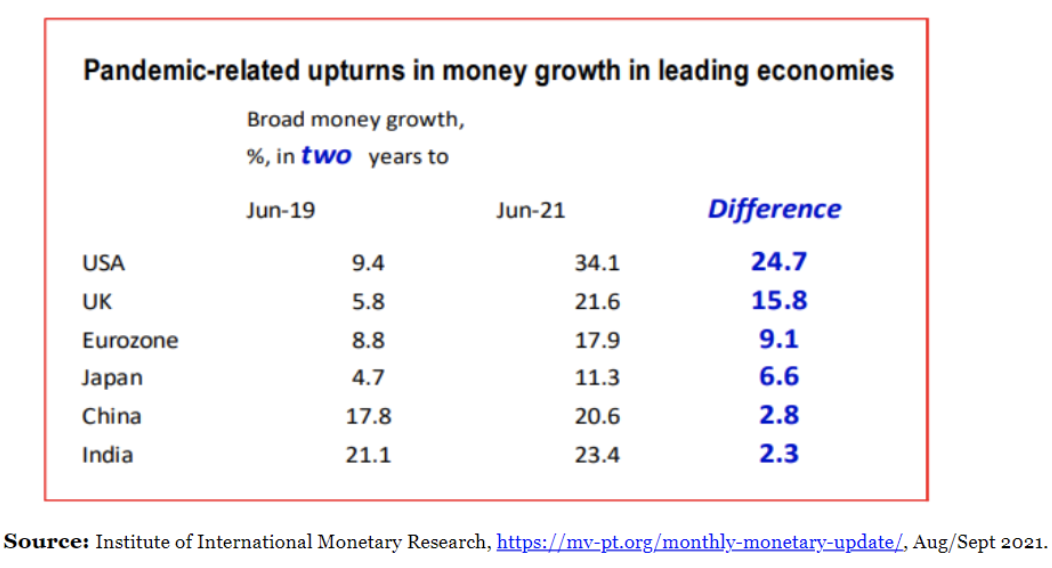

- “The British economist Tim Congdon (vor einigen Monaten zu Gast in meinem Podcast) is confident that he is in the process of being proved correct. Exhibit might be that the economies that really opened the monetary spigots two years ago now have a serious inflation problem, and those that didn’t don’t. For a reminder, this is how money growth accelerated over the main pandemic period:” – bto: ein durchaus eindeutiges Bild.

Quelle: Bloomberg

- “The orthodox counterargument to this is that some nonmonetary factors have obviously moved inflation as well. The shift in spending from services to goods and the huge supply chain interruptions caused by Covid-19 and then by the war in Ukraine come to mind.” – bto: Das stimmt, aber es ist eben doch die Mehrnachfrage, die durch die Inflation angeheizt wird.

- “But the monetarists can respond that there are still pockets of inflation unrelated to those factors. To quote Congdon’s latest newsletter: The increases in house prices on the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s ‘purchase-only’ index was 18.2% in the year to January. As yet, no meaningful cooling of the housing market has occurred, as the increase in the FHFA index in the three months to January was 4.1%, with an annualised rate of increase of 17.4%. Now comes the polemical point. It is plainly daft to attribute the remarkable increase in the price of houses – many of which were built a few decades ago – to energy prices, price movements in second-hand cars and lumber, the international shipping market and so on in 2020 and 2021. The correct interpretation is surely that rapid money growth sparked asset price inflation, which motivated a boom in aggregate demand, which took output far into over-heating territory, which led to soaring inflation in goods and services (…) Today’s supply shortages are a symptom of inflation, not a cause.” – bto: Das leuchtet ein, aber es ist bereits passiert und damit nicht mehr zu korrigieren. Also doch einfach auslaufen lassen?

- “Even if inflation is a monetary problem susceptible of a monetary cure that is already being administered, the peak might not yet be in. Friedman showed that monetary policy acts with a significant lag. The extra demand for wages, in particular, is still working its way through the system.” – bto: Man blicke auf die Forderungen in der aktuellen Tarifrunde.

- “Much hope has been put in ‘base effects’ as April, May and June of last year all saw very high rises in prices. However, Congdon points out that from July to September monthly inflation was much lower — 0.45%, 0.33% and 0.42% respectively. He goes on: The underlying rate of inflation in the USA – driven by domestic labour costs, above all – is now well above these figures. Suppose that the monthly CPI increases in July, August and September are ¾%, which seems reasonable. Then the annual rate of increase for September – announced in October – will be about 1% above that for June – announced in July.” – bto: Andererseits warnt Congdon aber auch davor, zu stark auf die Bremse zu steigen.

- “As some are already stating as fact that inflation has peaked, this prediction would mean horrible things for asset markets if it came true. It also implies that the monetary policy must be steadfast and aggressive. Many people in markets now are hoping that the monetarists are wrong.” – bto: Es ist gut denkbar, dass die Zinserhöhung in einen Abschwung hinein erfolgt. Dazu ist das Wachstum der Geldmengen bereits zu gering.

Der unentgeltliche Newsletter von John Authers kann bei Bloomberg abonniert werden.