Neben der Überschuldung waren es vor allem die demografische Entwicklung und das schwache Produktivitätswachstum, die zur These der säkularen Stagnation beziehungsweise der Eiszeit geführt haben. Angesichts der guten Entwicklung der Weltwirtschaft mehren sich die Stimmen, die ein Ende der Eiszeit ausrufen und feststellen, dass die These der säkularen Stagnation falsch war:

→ Ende der Eiszeit in Sicht?

Und zur Erinnerung meine These in Kurzfassung:

→ Zur Erinnerung: Stelters Eiszeit-These

Nun kommen die von mir hoch geschätzten Kollegen von McKinsey mit einer optimistischen Studie auf den Markt. Die Aussage überrascht eigentlich nur dahingehend, dass es die Kollegen überrascht hat. Es genügt nicht, dass ein Unternehmen neue Ideen hat etc., es bedarf auch einer entsprechenden Nachfrage. Wenn diese fehlt, bestehende Anlagen also unausgelastet sind und Arbeitskräfte billig, dann kommt es nicht zu Produktivitätsfortschritten. Das ist doch nun wirklich nicht überraschend, hätte ich da gesagt. Aber egal. Mit zunehmendem Boom soll demzufolge auch das Produktivitätswachstum wiederkommen. Ich würde sagen, das stimmt. Die Frage ist nur, werden Boom und Auslastung weiter anhalten? Und: Welche Wirkung hat es, dass ein immer größerer Teil der Bevölkerung nicht mehr mitkommt? Ich meine jetzt (noch) nicht Deutschland, sondern Länder wie die USA, wo die Beschäftigungsquote deutlich gesunken ist. Menschen, die nicht arbeiten, reduzieren die gesamtwirtschaftliche Produktivität.

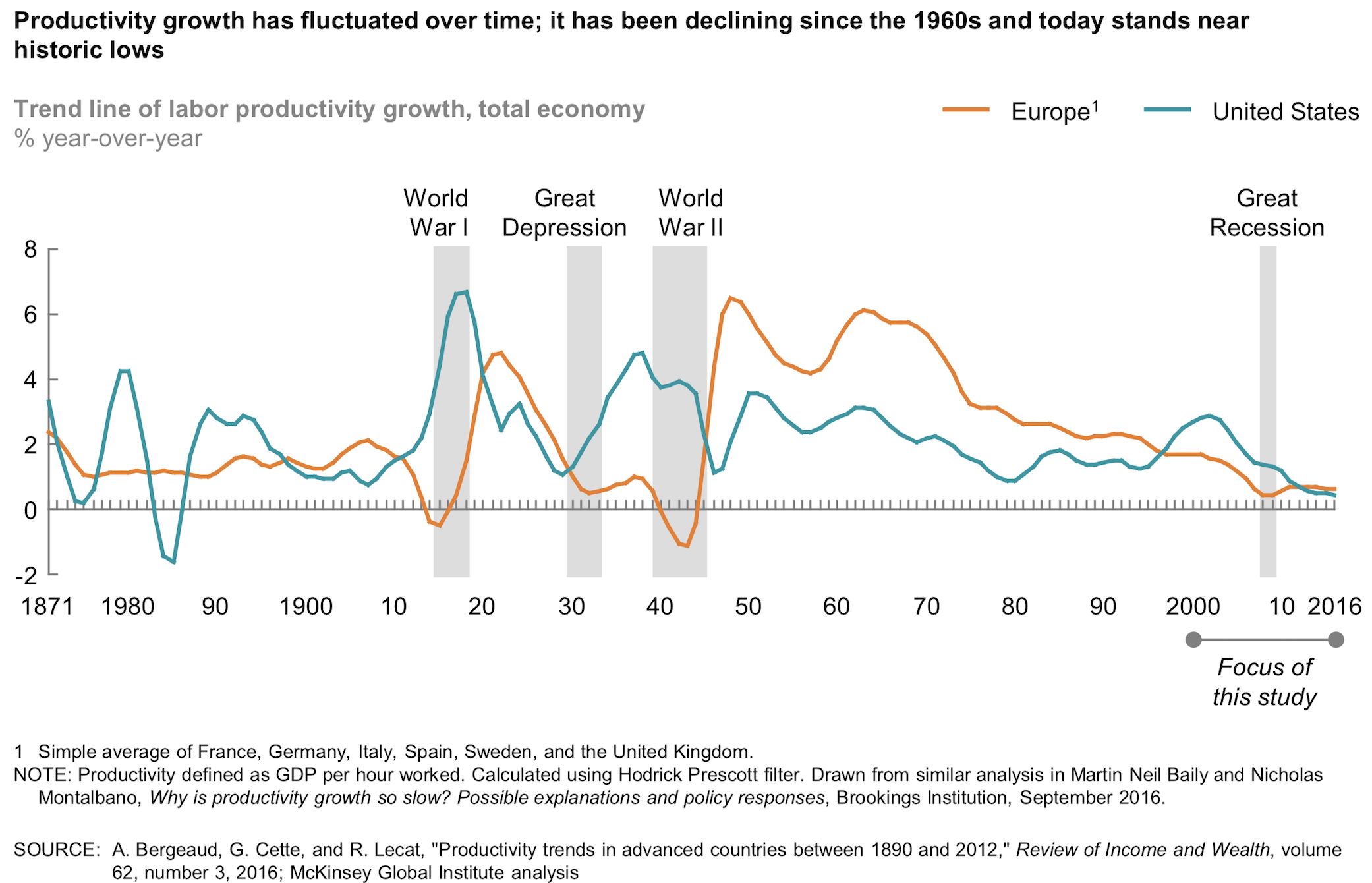

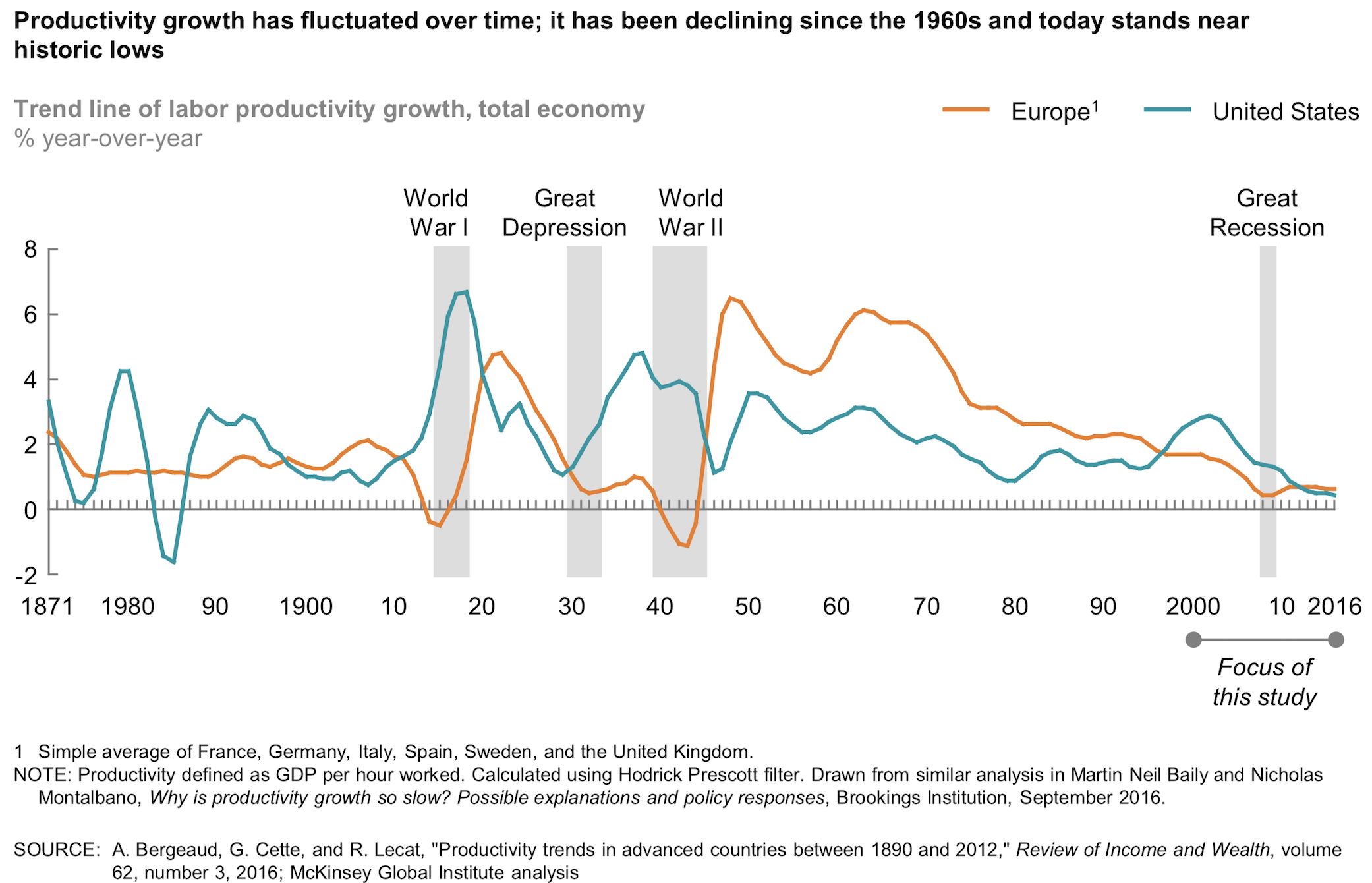

Zunächst die Erinnerung an die Entwicklung der letzten Jahre:

Quelle: McKinsey

Die New York Times berichtet:

- “(…) McKinsey researchers have tried to understand what drives productivity growth from the ground up. They’ve studied how innovations that enable a company to make more goods and services per hour of labor spread across the economy.The latest wrinkle is that the researchers now believe that productivity growth depends not just on the supply side of the economy — what companies produce and what technologies they use to do it — but also significantly on the demand side.” – bto: Man braucht halt eine entsprechende Auslastung. O. k.

- “Automobile production in the United States fell 50 percent from 2007 to 2009, meaning the sector had tremendous excess production capacity in the ensuing years even as the sector recovered. (…) Typically the newest technology is implemented in the latest factories. People don’t upgrade a factory that can fulfill demand perfectly well.” – bto: Ja, so einfach ist es. Es muss sich lohnen zu investieren. Übrigens tragen die Zombies zu geringem Wachstum bei, weil sie genau diese produktivitätssteigernden Investitionen nicht tätigen.

- “The basic technology for self-serve kiosks has been around for years. But when the unemployment rate was at its post-crisis highs, employers could have their pick of good workers at relatively low prices. Now, with the jobless rate at 4.1 percent, good workers are harder to find. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, companies have been more open to installing technology that may have a significant upfront cost and require reworking how a restaurant is organized, but allow more sales without hiring more workers.” – bto: So ist es, schönes Beispiel übrigens. Sie meinen die Verkaufsautomaten bei McDonalds etc.

- “The optimistic case for both productivity and overall economic growth goes like this: (…) with companies having a harder time finding qualified workers and with demand for their products rising, they’ll have no choice but to re-engineer how they work to try to increase productivity. Higher productivity will in turn make it easier to justify higher wages, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of higher economic growth.” – bto: was aber nicht richtig ist. Es trifft nur einen Teil der Bevölkerung, und wenn wir diesen Weg gehen (was wir werden), schaffen wir ein immer größeres Proletariat, das technologisch abgehängt ist.

- McKinsey sieht das auch: “Unless displaced labor can find new highly productive and high-wage occupations, workers may end up in low-wage jobs that create a drag on productivity growth (…).” – bto: wenn sie überhaupt noch Arbeit finden.

Fazit der New York Times: First we have to see if the theory holds up — that a tighter economy will feed into higher capital investment and experimentation by businesses about finding new efficiencies. Then we have to see whether that feeds into a virtuous cycle in which more productivity creates more growth and vice versa. And then we have to hope that it turns into wage gains for workers who haven’t seen many of them in the last decade — or else it just may not last.” – bto: Ich denke, es ist eine nicht so überraschende Nachricht. Besser verkauft, als es der Inhalt wirklich rechtfertigt.

→ New York Times (Anmeldung erforderlich): “The Economy Is Getting Hotter. Is a Productivity Boom Next?”, 21. Februar 2018

→ McKinsey: “Solving the productivity puzzle”, Februar 2018