Keine Ausrede bei öffentlichen Schulden

Schon vor einigen Tagen habe ich auf eine neue Studie des IWF hingewiesen, die vorrechnet, wie schlecht es in Wahrheit um das „reiche“ Deutschland bestellt ist. Ganz so, als hätten die Autoren meinem Buch noch etwas Rückenwind geben wollen.

Nun greift auch die FT das Thema auf. Nach dem Motto, wer sein Vermögen besser managt, kann auch mit den Schulden besser umgehen:

- “The IMF’s report on the wealth of states, published at its joint annual meetings with the World Bank last week, may prove of more lasting significance than any of the hot topics the participants discussed, including trade conflicts, populism and looming financial instability.” – bto: Diesen Optimismus teile ich nun gar nicht.

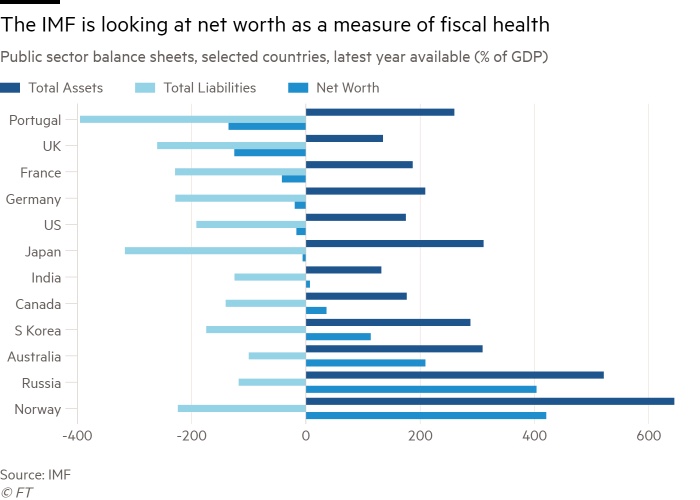

- “The fund has examined 31 countries amounting to 61 per cent of the world economy, whose total public sector assets it puts at $101tn, or more than double the countries’ annual gross domestic product. These include natural resources and financial claims (such as sovereign wealth funds), but also infrastructure and public corporations. It also measures liabilities, not just formal government debt (at 94 per cent of GDP on average) but other liabilities such as pensions. On average, governments have positive net worth — but the differences between countries are enormous, as the chart below shows.” – bto: Und es fehlen natürlich die absehbaren Defizite der Sozialkassen, für die letztlich auch der Staat einstehen muss.

Quelle: FT

- “The German government, meanwhile, has few assets, so its net worth is lower than that of Japan despite the latter’s huge gross debt liabilities.” – bto: Und da mag es natürlich wieder die Kritiker bei uns geben, denen die Aussage nicht passt und die sich dann – wie im konkreten Fall geschehen – über Twitter mokieren, dass es wohl nicht sein könne, dass Uganda reicher ist, als wir. Doch, das kann wohl sein, vor allem, wenn man so von der Substanz zehrt, wie das Deutschland tut.

- “Complete balance sheet accounts for governments remain exceedingly rare, and the IMF’s push for doing better is very welcome. (…) Understanding the asset side as well as the liability side (which itself is not fully understood by looking only at official debt measures) is important in part because what you don’t know can hurt you. Only a government that knows its assets well can make the best possible use of them — or be held to account by its citizens for its failure to do so.” – bto: Wenn es danach ginge, könnten wir den ganzen Bundestag nach Hause schicken.

- “The amounts are astounding: managing public financial assets and corporations half as profitably as private equivalents could bring in government financial revenues amounting to 3 per cent of GDP. But while managing assets more productively is, of course, a good idea, this does not mean higher public revenues are the best way to cash in the potential productivity gains. That is so even if such revenue gains were used to finance lower taxes or more public spending elsewhere.” – bto: was aber die Politik nicht möchte, denn dann müsste sie ja immer danach trachten, den Wohlstand zu erhöhen. So kann man Klientelpolitik betreiben …

- “An alternative is to use public assets more productively so as to expand or improve the provision of public goods they underpin; that will provide a macroeconomic benefit to the national economy even if it does not directly improve public finances.” – bto: Das gilt für den gesamten öffentlichen Bereich. Alleine eine Modernisierung und Digitalisierung der Verwaltung könnte Milliarden sparen und die Bürger massiv entlasten.

- “The reason governments and markets pay disproportionate attention to debt is that debt has regular deadlines by which it must be serviced — and failure to do so is devastating. The most intriguing promise held out by a better mapping of the asset side is to reduce vulnerabilities on the debt side. Simply showing a strong net worth position may itself improve markets’ view of debt sustainability in a high-debt country, for example. But, more profoundly, liabilities could be issued in ways that take the asset side better into account — reflecting its size and also its relative durability and illiquidity.” – bto: Eigentlich müssten die Zinsen in Deutschland viel höher sein, angesichts der schlechten Bilanz, zu der man die schlechte Bildung, die Kosten der Migration und die massiven Kosten des demografischen Wandels hinzurechnen müsste.

- “Why should governments behave like banks and hedge funds, funding long-term illiquid assets with often short-term market debt? One answer would be that they can print money to redeem debt; but well-run countries have, for good reasons, decided to devote monetary policy to price stabilisation, not debt financing.” – bto: Und wie wir in der Eurozone sehen, haben nicht alle unbegrenzten Zugriff auf die Notenbank.

- “So it may be worth (…) to think more creatively about matching it to the liability side. That would mean getting investors used to long-term, illiquid placements to match government assets, in return for their superior safety — and their likely superior return when well-managed. That would reduce financial risks for governments. If it created funding markets for long-term illiquid investments in the private sector as well, so much the better.” – bto: Ja, das mag alles gut sein. Ich denke aber, der Hauptnutzen läge darin, Politiker an der Schaffung von Wohlstand messen zu können. Man müsste dazu übrigens auch die künftigen Unterhalts- und Erneuerungskosten von heutigen Investitionen aufnehmen. Berühmtes Beispiel sind die Schwimmbäder in Würselen und anderswo.