Ist MMT die Lösung?

Können die Staaten sich leisten, so viele neue Schulden zu machen? Die Befürworter der Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) sagen ganz klar „ja“. Dem kann man aber auch entgegentreten. In der FT kamen beide Seiten zu Wort:

Stephanie Kelton – wohl die bekannteste Vertreterin der MMT-Schule:

- „Gone, for now, are concerns about how to ‘pay for’ it all. Instead we are seeing wartime levels of spending, driving deficits — and public debt — to new highs. France, Spain, the US, and the UK are all projected to end the year with public debt levels of more than 100 per cent of gross domestic product, while (…) Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio will soar above 160 per cent. In Japan, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has committed to nearly $1tn in new deficit spending to protect a $5tn economy, a move that will push Japan’s debt ratio well above its record of 237 per cent.“ – bto: Das ist alles kein Problem, kostet doch Geld nichts und die Notenbanken stehen bereit.

- „In advanced economies, the IMF expects average debt-to-GDP ratios to be above 120 per cent in 2021. While most see big deficits as a price worth paying to combat the crisis, many worry about a debt overhang in a post-pandemic world. Some fear that investors will grow weary of lending to cash-strapped governments, forcing countries to borrow at higher interest rates. Others worry governments will need to impose painful austerity in the years ahead, requiring the private sector to tighten its belt to pay down public debt.“ – bto: Dies ist bei uns ja schon in vollem Gange – Steuererhöhungen, Vermögensabgaben, es nimmt gar kein Ende.

- „While public debt can create problems in certain circumstances, it poses no inherent danger to currency-issuing governments, such as the US, Japan, or the UK. (…) There are three real reasons. First, a currency-issuing government never needs to borrow its own currency. Second, it can always determine the interest rate on bonds it chooses to sell. Third, government bonds help to shore up the private sector’s finances.“ – bto: Der letzte Punkt ist der wichtige. Je mehr Schulden der Staat macht, desto reicher ist der Privatsektor. Wir müssen also viele Staatsschulden haben, damit wir reich sind. Mit Blick auf Deutschland und Italien ist man geneigt, das genauso zu sehen. Wir sind ärmer, weil der Staat nicht genug Schulden hat. Übrigens: Dann gibt es erst recht keine Notwendigkeit für europäische Solidarität.

- “The first point should be obvious, but it is often obscured by the way governments manage their fiscal operations. Take Japan, a country with its own sovereign currency. To spend more, Tokyo simply authorises payments and the Bank of Japan uses the computer to increase the quantity of Yen in the bank account. (…) The Japanese government can afford to buy whatever is available for sale in its own currency. True, it can spend too much, fuelling inflationary pressure, but it never needs to borrow Yen.“ – bto: Wir können uns alles leisten, weil wir keine Budgetrestriktion haben.

- „If that is true, why do governments sell bonds whenever they run deficits? Why not just spend without adding to the national debt? It is an important question. Part of the reason is habit. Under a gold standard, governments sold bonds so deficits would not leave too much currency in people’s hands. Borrowing replaced currency (which was convertible into gold) with government bonds which were not. In other words, countries sold bonds to reduce pressure on their gold reserves. But that’s not why they borrow in the modern era.“ – bto. weil wir eben kein Gold mehr nutzen, sondern Zahlen am Bildschirm.

- „Sovereign bonds are just an interest-bearing form of government money. The UK, for example, is under no obligation to offer an interest-bearing alternative to its zero-interest currency, nor must it pay market rates when it borrows. As Japan has demonstrated with yield curve control, the interest rate on government bonds is a policy choice. So today, governments sell bonds to protect something more valuable than gold: a well-guarded secret about the true nature of their fiscal capacities, which, if widely understood, might lead to calls for ‘overt monetary financing’ to pay for public goods. By selling bonds, they maintain the illusion of being financially constrained. In truth, currency-issuing governments can safely spend without borrowing.“ – bto: Nun kann man mit Blick auf frühere Experimente in diese Richtung festhalten, dass sie nicht so richtig erfolgreich waren. Weimar, Simbabwe, Venezuela …, aber wie auch beim Sozialismus könnte es ja daran liegen, dass sie es einfach nicht richtig gemacht haben.

Edward Chancellor hält dagegen:

- „Adherents of this unorthodox school of economics would have us believe, like Alice in Wonderland, six impossible things before breakfast. Governments can never go bust. They don’t need to raise taxes or issue bonds to finance themselves. Borrowing creates savings. Fiscal deficits are not the problem, they are the cure. We could even pay off the national debt tomorrow.“ – bto: Und das wäre doch super. Wir hätten endlich keine Probleme mehr und könnten alles finanzieren. Green Deal usw.

- „As theory, MMT has been rejected by mainstream economists. But as a matter of practical policy, it is already being deployed. Ever since Ben Bernanke, as governor of the US Federal Reserve, delivered his ‘helicopter money’ speech in November 2002, the world has been moving in this direction. As president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi proved that even the most indebted countries need not default. Last year, the US federal deficit exceeded $1tn at a time when the Fed was acquiring Treasuries with newly printed dollars — that’s pure MMT.“ – bto: und? Es ist nichts passiert. So einfach ist es. Wir haben doch damit den Beweis, dass MMT keine negativen Nebenwirkungen hat. Zumindest nicht im Umfeld schwachen Wachstums und damit ohnehin deflationärer Tendenzen.

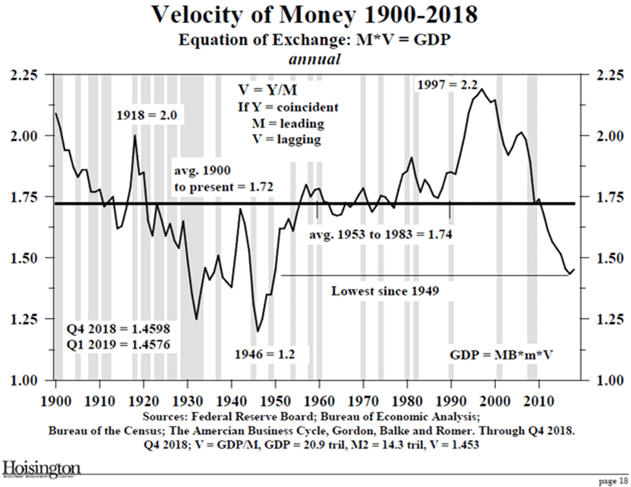

Das liegt auch daran, dass die Umlaufgeschwindigkeit des Geldes stetig abnimmt:

- „Fiscal and monetary policy are now being openly co-ordinated, just as MMT recommends. The US budget deficit is set to reach nearly $4tn this year. But tax rises are not on the agenda. Instead, the Fed will write the cheques. Across the Atlantic, the Bank of England is directly financing the largest peacetime deficit in its history. MMT claims that money is a creature of the state. The Fed’s share of an expanding US money supply is close to 40 per cent and rising. Again, we are seeing MMT in practice.“ – bto: Und die Eurozone wird zu irgendeinem Punkt noch deutlich aufholen, nichts anderes wird nötig sein, um die Währungsunion vor dem Kollaps zu bewahren – zumindest um Zeit zu kaufen.

- „During crises, the public has an abnormally high demand to hold cash; debt monetisation appears less of a problem. But governments can print money to cover their costs for only as long as the public retains confidence in a currency. When the crisis passes, the excess money must be mopped up. Proponents of MMT claim this shouldn’t be a problem.“ – bto: Konkret denkt man dann an höhere Steuern oder eben doch an die Ausgabe von Anleihen.

- „But then they admit that nobody has a good inflation model. We cannot accurately measure the economy’s spare capacity, either. This means that politicians are unlikely to raise taxes in time to nip inflation in the bud. Bonds can always be issued to withdraw money from circulation. But once inflation is under way, bondholders demand higher coupons.“ – bto: Die einzigen Politiker, die das wollen, sitzen in Deutschland. Ansonsten argumentiere ich in die gleiche Richtung. Geht das Vertrauen verloren, steigt die Umlaufgeschwindigkeit und damit die Inflation.

- „Great historic inflations have been caused not by monetary excesses but by supply shocks, say MMT exponents. It’s likely that coronavirus will turn out to be one of those shocks. Besides, history casts doubt on attempts to explain inflation by non-monetary factors. The closest example of MMT in implementation comes from France’s experiment with paper money. In 1720, the Scottish adventurer John Law served as French finance minister and head of the central bank. The bank printed lots of paper money, the national debt was repaid and France enjoyed brief prosperity. But inflation soon took off and crisis ensued.“

Den Vergleich mit John Law hatten wir auch schon mal beim Thema MMT:

→ MMT eine Neuauflage der Ideen John Laws?

- „The truth is that governments have an inherent bias towards inflation, especially under adverse conditions such as wars and revolutions. The Covid-19 lockdown is another such condition. Tomorrow’s inflation will alleviate some of today’s financial problems: debt levels will come down and inequalities of wealth will be mitigated. Once excessive debt has been inflated away, interest rates can return to normal. When that happens, homes should be more affordable and returns on savings will rise. But the evils of inflation should not be overlooked. Economies do not function well when everyone is scrambling to keep pace with soaring prices. Inflations produce their own distributional pain. Workers whose incomes rise with inflation do better than retirees. Debtors will thrive at the expense of creditors. Profiteers arise, along with populists who feed on social discontents. Modern monetary practices ensure another inflation is around the corner. MMT provides the intellectual gloss.“ – bto: Ich würde sagen, sie ist nicht um die Ecke, aber mittelfristig zu erwarten. Angesichts mangelnder Alternativen sollten wir das so hinnehmen.