Ist die demografische Entwicklung doch nicht inflationär?

In der Vergangenheit habe ich mehrfach die These diskutiert, dass die demografische Entwicklung für eine Rückkehr der Inflation spricht. Ich hatte die Vertreter der These auch in meinem Podcast zu Gast:

→ Inflation oder Deflation – es ist ein schmaler Grat

→ Das Comeback von Inflation und Zins – Originalinterview

Aber vielleicht überzeugt die These doch nicht? So zumindest die Gedanken, die John Authers von Bloomberg bereits im Frühjahr 2021 in seinem kostenfreien Newsletter – der wirklich sehr lesenswert ist – zusammengefasst hat:

- “One of the most interesting and persuasive arguments that a shift toward secular inflation is under way (…) is the idea of a great demographic reversal. In their eponymous book, Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan argued that the shift to a grayer population will lead to more inflation, as old people spend rather than save, while a shrinking number of workers have greater negotiating power to push up wages. The forthcoming change in China’s demographics, following years when its growing workforce helped keep prices low in the developed world, is also part of the argument for secular lower inflation.” – bto: Das leuchtet auch mir intuitiv ein.

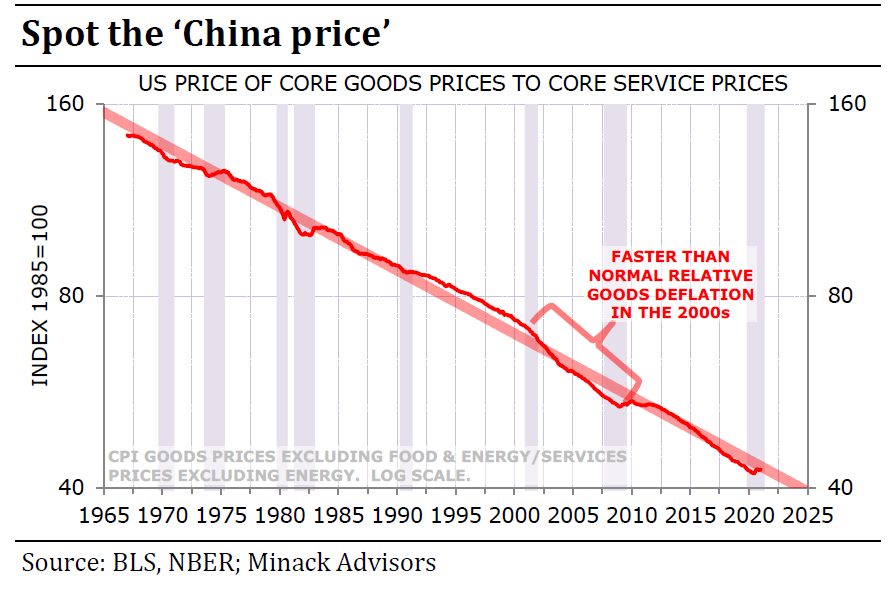

- “Gerard Minack (…) makes the point that the price of goods compared to services had been tumbling in the U.S. for decades before the entry of China into the world economy in a big way at the beginning of this century. Improved productivity and automation might help explain this. The following chart shows that China’s accession to the World Trade Organization simply accelerated the trend. China’s entry, in short, isn’t as big a deal for inflation as some think it is.” – bto: Dass wir in einem kapitalistischen System eine strukturelle Tendenz zur Deflation haben, ist klar. Wir sind in einer Produktivitätsmaschine und die muss so wirken, wenn man sie lässt.

Quelle: Bloomberg

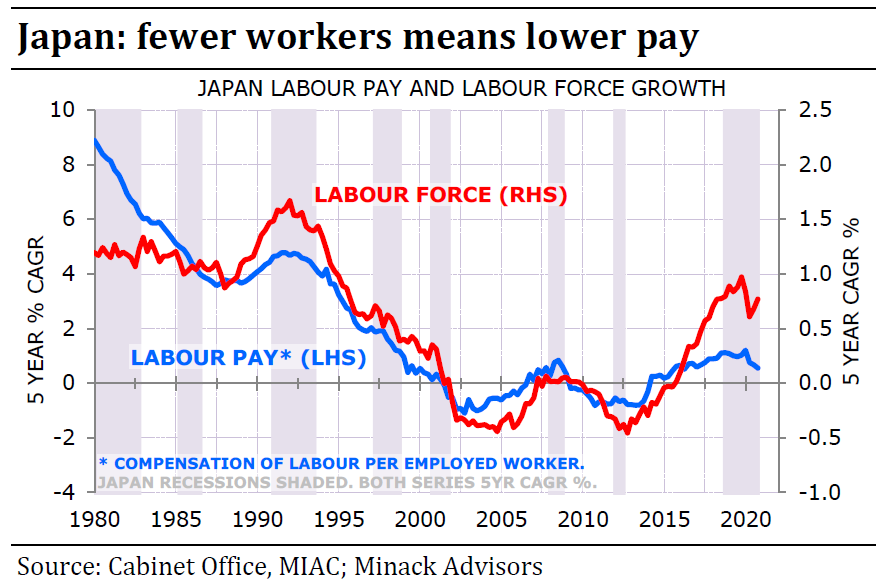

- “Now we come to Japan. A key Goodhart/Pradhan argument is that a smaller labor force, as a proportion of the population, will lead to greater negotiating power and more wage inflation. But as Minack shows, declines in the workforce have been matched by declines in pay, while Japanese workers have gained a better deal for themselves, contrary to theory, when their numbers have risen.” – bto: Folgendes müssen wir allerdings im Hinterkopf haben: a) Die Produktivität pro Erwerbstätigen ist in den letzten Jahren mehr gewachsen als bei uns und in den USA. b) Japan hat in dieser Zeit auch von der Weltwirtschaft und vom Outsourcing nach China profitiert.

Quelle: Bloomberg

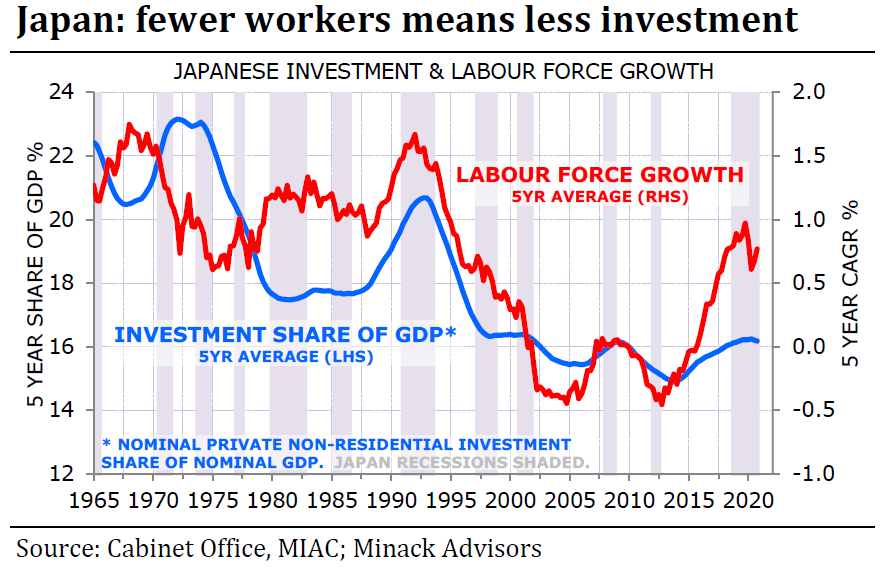

- “A population with more old people will save less, and therefore spend more; therein lies the argument for inflation. But Minack argues that an older population with more retirees will also invest less, and that could be a more important driver of inflation than spending. If we look at investment’s share of GDP compared with fluctuations in Japanese labor force growth, the relationship is clear.” – bto: Mit Blick auf Deutschland könnte man sagen, dass das stimmt. Ich möchte jedoch zusätzlich anmerken, dass der Höhepunkt der Investitionen in Japan Ende der 1980er-Jahre mit einer historischen Blase einherging. Insofern weiß ich nicht, ob das so stimmt. Hinzu kommt, dass wir weltweit einen Rückgang der Investitionen beobachten konnten.

Quelle: Bloomberg

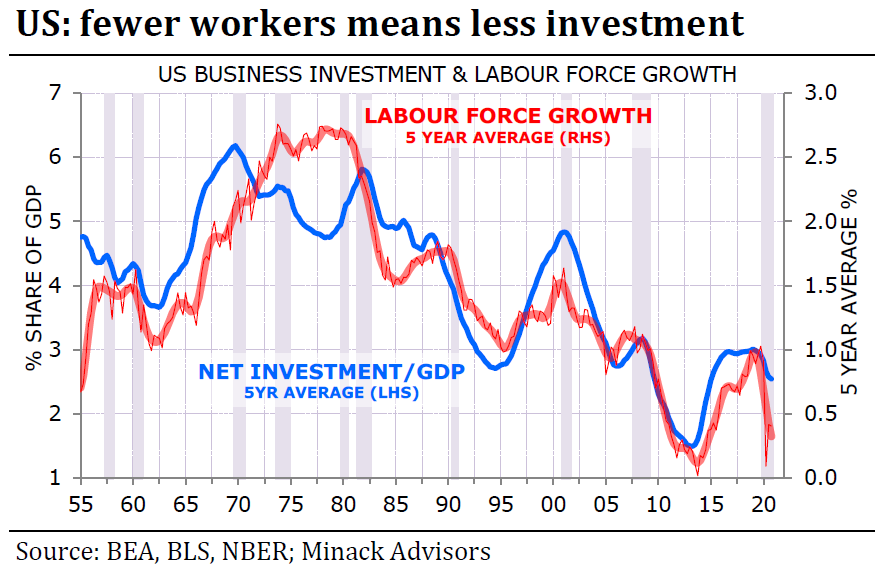

- “Repeating the same exercise for the U.S. reveals if anything a tighter relationship. So the Minack argument is that a nation with more retirees will be one that makes even less attempt to invest for growth, and thus stays in the same horrible slow-growth conditions of the last decade.” – bto: Oder die Investitionen finden in anderen Regionen der Welt statt?

Quelle: Bloomberg

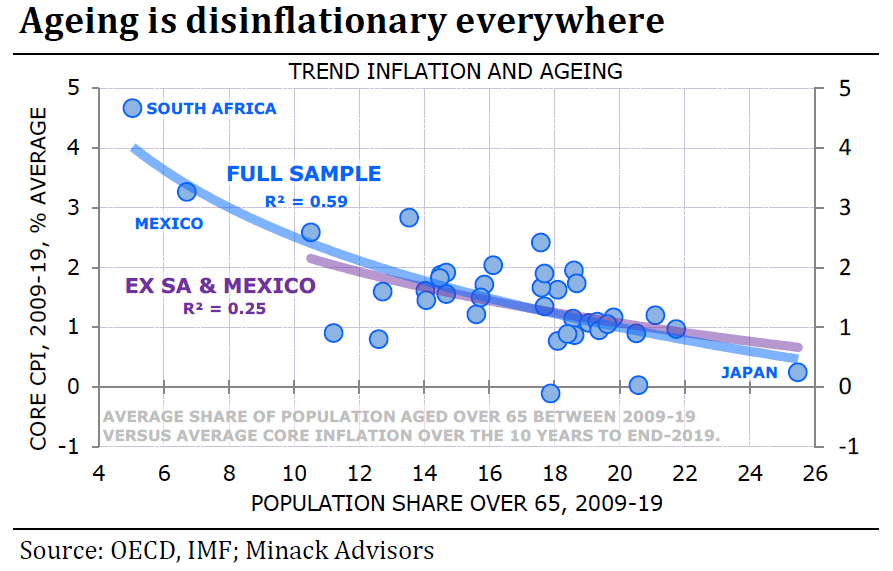

- “(…) a fascinating chart build with data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which matches average core inflation for the last decade on one scale against the population over 65 on the other. Japan has a very elderly population and minimal inflation. South Africa and Mexico, much younger nations, had the highest inflation in the OECD (although Mexico’s was still barely over 3%). Keeping these two outliers in the sample, the correlation between trend inflation and elderly population is a respectable 59%; without them, it drops to 25% among the sample of mostly well developed nations that remain. The basic point is that to date ageing has been associated with lower, not higher inflation.” – bto: Das bedeutet dennoch, dass wir uns nicht darauf verlassen können. Oder ist es dann egal, was Notenbanken (Drucken) und Staaten (Ausgaben, Klima usw.) machen? Ich denke nicht.

Auf jeden Fall ein spannendes Thema.