Geldmenge und Inflation – der Zusammenhang

Wir nähern uns dem schwierigen Thema “Inflation” an. Dabei spielt – wie auch die Diskussion zu vergangenen Podcasts zum Thema gezeigt haben – die Theorie der Geldmenge und der Wirkung auf das Preisniveau eine Rolle. Professor Richard A. Werner setzt sich mit den Notenbanken sehr interessant auf seinem Blog auseinander:

Heute geht es aber um den Aspekt der Geldmenge. Den analysiert er in einem Beitrag für die Royal Economic Society:

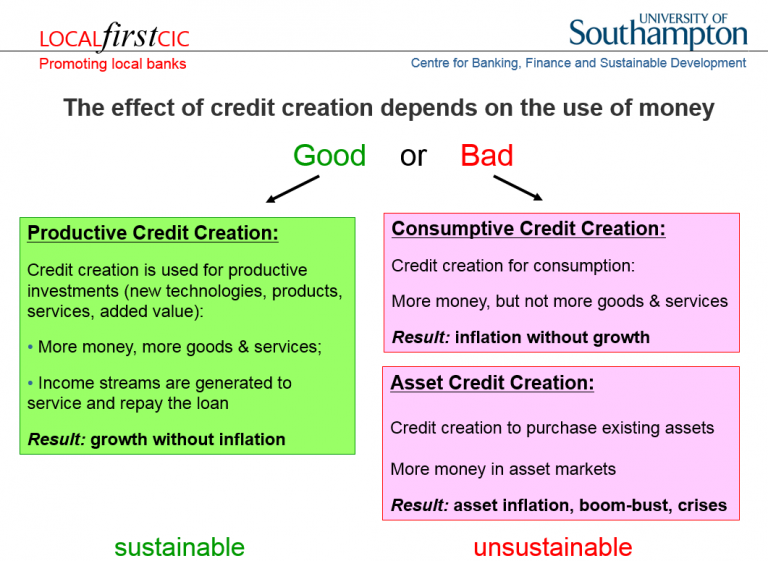

- “(The) ‘Quantity Theory of Credit’, (…) is arguably the simplest empirically-grounded model that incorporates the key macroeconomic role of the banking sector (…) The central argument is a dichotomous equation of exchange distinguishing between money used for GDP-transactions (determining nominal GDP) and money used for non-GDP transactions (determining the value of asset transactions).” – bto: Ich denke, dies ist eine sehr wesentliche Unterscheidung. Ich spreche immer von produktiven und unproduktiven Krediten. Es ist so simpel und einleuchtend, dass ich mich frage, weshalb es von den meisten Ökonomen nicht betrachtet wird.

Quelle: Prof. Richard A. Werner

- “Growth requires increased transactions that are part of GDP, which in turn requires a larger amount of money to be used for such transactions. The amount of money used for transactions can only rise if banks create more credit. Banks newly invent the money that they lend by pretending that the borrowers have deposited it and thus crediting their accounts without transferring any money from elsewhere. This expands the money supply and it suggests that the accurate way to measure this money is by bank credit.” – bto: Richtig, Geld entsteht aus einem Verschuldungsakt und ist deshalb nichts anderes als umlauffähige Schulden.

- “It can be disaggregated into credit for GDP transactions (CR) and credit for non-GDP (i.e. asset) transactions (CF). The former drives nominal GDP and the latter asset transaction values. Under further conditions, they determine consumer and asset prices:”

Quelle: Prof. Richard A. Werner

C = Credit/Money

V = Velocity (Umlaufgeschwindigkeit)

P = Preisniveau

Y = Warenangebot/-nachfrage (reales Angebots/Nachfrageniveau der Volkswirtschaft), Produktion.

- “This simple model explains a number of empirical anomalies, including the often reported lack of empirical significance or the ‘right sign’ of interest rates as explanatory variable of economic activity (rates are not the cause of growth; they do not appear in the model); the ‘velocity decline’, which is due to the neglect of asset transactions in the standard quantity equation; why interest rate reductions and fiscal expansion of historic proportions failed to trigger a sustained recovery in Japan (rates do not cause growth; pure fiscal policy is growth neutral since it does not create credit); what makes banks special and how their activities are related to growth (their creation of money for GDP transactions is the necessary and sufficient condition for nominal GDP growth). It also explains asset price determination and the ‘recurring banking crises’.” – bto: Darin stecken alle Erkenntnisse von Werners Überlegungen.

- “So the effect of bank credit depends on its quantity and quality — the latter defined by whether it is used for unproductive transactions (credit for consumption or asset transactions, producing unsustainable consumer or asset inflation, respectively) or productive transactions (delivering non-inflationary growth). Credit used for productive transactions aims at income growth and is sustainable; credit for asset transactions aims at capital gains and is unsustainable. When credit creation slows after an asset bubble driven by credit for asset transactions, the ensuing fall in asset prices, capital losses and non-performing loans can easily trigger a banking crisis.” – bto: Und deshalb geht es langsam hoch und schnell nach unten. Alles, was auf Kredit basiert, ist inhärent instabil.

- “The QTC suggests that neither interest rate reductions nor fiscal expansion, nor reserve expansion, nor structural reforms would be able to stimulate nominal GDP growth. Based on this model I proposed in 1994 and 1995 that a new type of monetary policy be implemented in Japan, which aimed not at lowering the price of money, or expanding monetary aggregates, but at the expansion of credit creation for GDP transactions. (…) I suggested in numerous publications that the central bank purchase non-performing assets from the banks to clean up their balance sheets, that the successful system of ‘guidance’ of bank credit should be re-introduced, that capital adequacy rules should be loosened not tightened, and that the government could kick-start bank credit creation and thus trigger a rapid recovery by stopping the issuance of bonds and instead entering into loan contracts with the commercial banks.” – bto: wobei ich denken würde, dass die Ausgabe von Bonds, die von Banken gekauft werden, auch neues Geld schafft?

- “My articles caused consternation among economists of diverging schools of thought. The Keynesians, such as Richard Koo, disputed that further monetary stimulation of any kind was needed and that fiscal policy on its own was going to be ineffective. The government listened to Mr Koo, and Japan continued to expand its national debt in massive spending programmes, while credit growth continued to stagnate. So did the economy. Monetarists, such as Peter Morgan or Alan Meltzer, likewise argued that a lack of bank credit was not a problem and ‘quantitative easing’ in the form of credit creation was not needed. Instead, they argued, an expansion in bank reserves at the central bank would do the job. But massive reserve expansions failed to make any impact and due to stagnating bank credit, economic growth remained well below its potential for most of the following decade and a half. Supply-side economists and proponents of real business cycle models argued that a lack of bank credit could not be the problem — after all, their models did not include banks! I warned during the 1990s that fiscal expansion funded by bond issuance was likely to crowd out private demand, that the expansion of bank reserves would have no impact as idle reserves do not translate into bank credit growth when banks are risk-averse, and that structural reform, if able to increase productivity (which is doubtful) would merely boost potential growth, while Japan’s economy had remained in recession due to a lack of demand.” – bto: Vor allem geben Banken dann keine Kredite, wenn ihr Eigenkapital eigentlich schon weg ist. Es leuchtet aber ein, dass es um Kreditwachstum geht. Warum Anleihen nicht zählen? Vermutlich, weil die Bank beim Kauf kein neues Geld schafft. Beim Kredit verlängert sie die Bilanz, beim Kauf von Anleihen handelt es sich um einen Aktivtausch.

- “This did not stop the Bank of England from adopting a similar policy in March 2009, with the variation that bond purchases would be made from the non-bank private sector. Better still would have been to boost bank credit by directing any central bank asset purchases to non-performing bank assets. As a result, UK-style QE also failed as bank credit growth continued to stagnate (Lyonnet and Werner, 2012). Meanwhile, Ben Bernanke, who participated in the debates on Japanese policy in the 1990s, seemed to have listened more carefully: In his January 2009 speech at the LSE he insisted that the Fed was not engaging in Bank of Japan-style QE, since reserve expansion would not work, and instead was pursuing a policy more directly targeting credit, which he called ‘credit easing’. This seemed to take us full circle to the original meaning of QE. And the US purchases of non-performing bank assets did seem to do the job of allowing banks to create credit again (with credit growth reaching over 5 per cent by early 2013, and the US economy recovering).” – bto: Vereinfacht gesagt geht es darum, die Kreditvergabe zu fördern, weil nur die Kreditvergabe zu Mehrnachfrage führt.

- “(…) a successful quantitative monetary stimulation policy needs to be ‘designed to incentivise banks and building societies to boost their lending to UK households and private non-financial corporations — the “real economy”’ or CR of equation (2). (…) Direct targeting of bank credit by the central bank, relaxation not tightening of capital adequacy rules and, most of all, switching the funding method of the public sector borrowing from bond issuance to borrowing from banks, remain surer bets.” – bto: weil damit die Kreditmenge wächst. Allerdings muss man dann immer noch dafür sorgen, dass diese Kredite in die Realwirtschaft fließen und nicht der Spekulation dienen.

- “The same applies to Europe. Nominal GDP contractions, record unemployment and widespread corporate bankruptcies in Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Greece are driven by credit contractions. Governments can end this by adopting true quantitative easing, easiest in the form of stopping bond issuance and instead borrowing from the banks in their countries.”

Ich denke, es ist wichtig, diese “Kredit = Geld-Logik” aufzunehmen für die Diskussion um Inflation und Wachstum. Um eine realwirtschaftliche Wirkung zu entfalten, müssten wir zwingend darauf achten, dass das neue Geld wirklich zusätzliche Nachfrage schafft. Ich denke, wenn die Notenbanken direkt den Staaten Kredit geben, machen sie genau das.

→ res.org.uk: “Quantitative Easing and the Quantity Theory of Credit”, 1. Juli 2013