Folgt Europa Japan in das deflationäre Szenario (II)?

Nach dem skeptischen Blick auf die Eurozone durch die japanische Brille von heute Morgen, nun ein anderes Team der Deutschen Bank mit mehr Hoffnung (How Europe is different from Japan). Schauen wir uns die Argumentation an:

- “For the purpose of this piece, a Japan scenario could be defined as a situation in which there is a large private sector credit bubble that bursts. The private sector deleveraging is slow and is not accommodated by either aggressive fiscal or monetary policy. As a result, the credit impulse (i.e. the pace of deleveraging) never reverses, and domestic demand remains under pressure. Ultimately, the economy converges to a situation in which inflation is negative and the output gap is widening while real interest rates are too high. This dynamic is exacerbated by population ageing and a weak banking sector.” – bto: Man könnte es als Bilanzrezession (Richard Koo) oder als Schuldendeflation (Irving Fisher) oder aber als deflationäre Depression in Zeitlupe (Stelter) bezeichnen. Das Ergebnis ist das gleiche.

- “To assess if Europe’s experience is similar to Japan in the 90s, we analyse the evolution of key economic and financial variables during each region’s respective crisis episode. (…) In practice, we set as a reference date (t=0) the peak in credit growth (Q1-90 in Japan and Q4-07 in the US and Europe) to compare the relevant variables in event time. We find that Europe in aggregate resembles the US (with a 3-4 year lag) more than Japan.” – bto: Das ist nur vordergründig eine gute Nachricht, denn auch die USA befinden sich – zumindest, wenn man der Eiszeit-These von Albert Edwards folgt – auch auf dem Weg in das japanische Szenario und ist uns nur wenig hinterher. Aber schauen wir mal, was hier gezeigt wird.

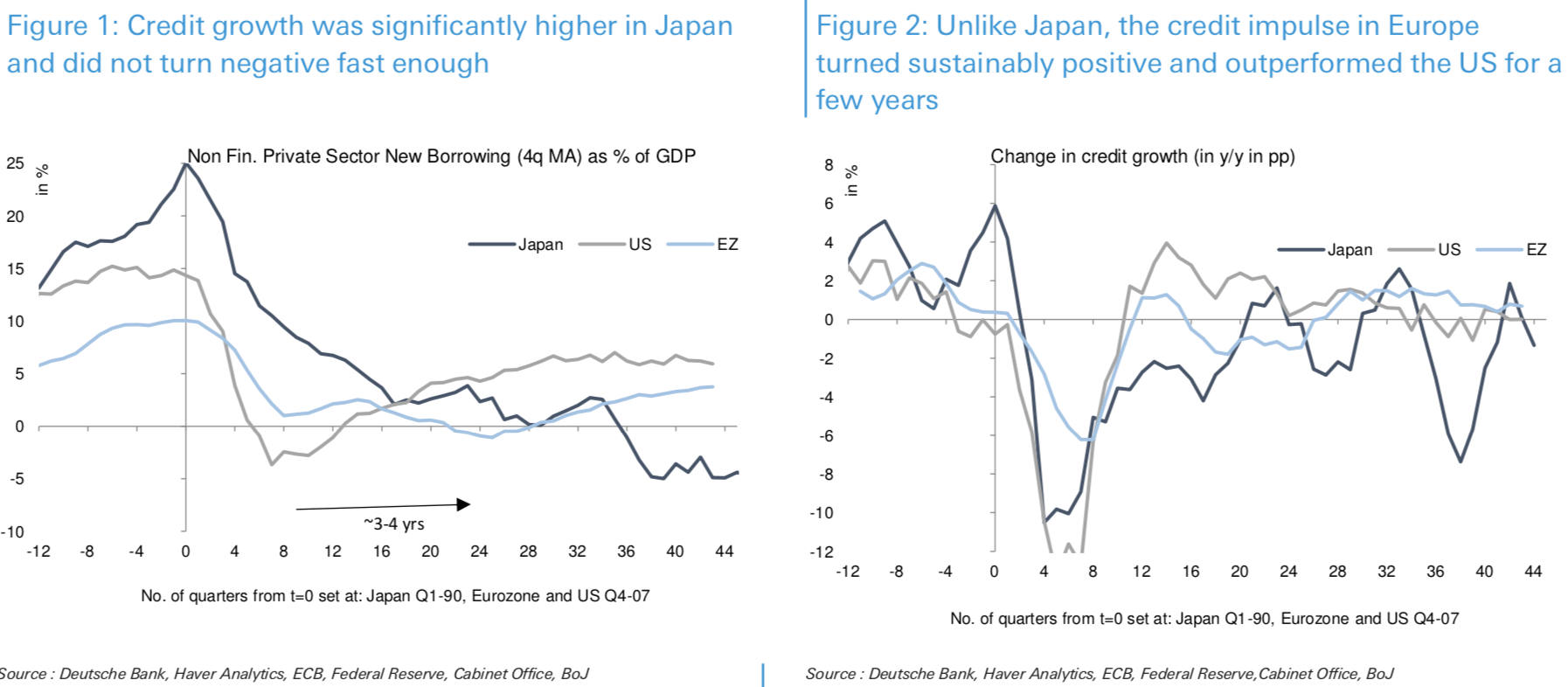

- Im Vordergrund steht also das Kreditwachstum: “In Japan, credit growth rose from ~10% of GDP to ~25% in the early 90s. Credit growth rose to ~15% in the US and ~10% in Europe ahead of the 2008 crisis. Thus, the overall scale of the credit overhang appears smaller in Europe. In Japan, credit growth adjusted slowly and did not turn negative before the late 90s. In the US, credit growth turned negative after 1.5 years, quickly reaching -3.7%. In Europe, it turned negative 3.5 years after the US reaching -1.1% (left graph below). Subsequently, the credit impulse in the US and Europe recovered, while it never turned sustainably positive in Japan (right graph below).” – bto: Also ist die These, dass die Schuldenblase bei uns geringer war und deshalb die Krise nicht so nachwirkt. Das könnte sein. Allerdings betonen die Autoren gleich am Anfang, ihre Aussagen träfen nur für die gesamte Eurozone zu, nicht für die jeweiligen Teile. Das allein zeigt allerdings schon, dass wir die gefährlichen politischen Implikationen vergessen.

Danach erinnert die Bank daran, dass man mit Kreditwachstum die Wirtschaft (temporär) pushen kann – allerdings zum Preis künftig tieferen Wachstums, wie wir wissen: “During the period of positive credit impulse, the economy is likely to be growing above potential, reducing the unemployment gap. In fact, for 3 years, the credit impulse in Europe was higher than in the US. During this period Europe outperform- ed its growth potential and consensus more than the US.” – bto: Wir müssen einfach nur viel mehr Schulden machen – wie die USA – dann bekommen wir auch mehr Wachstum.

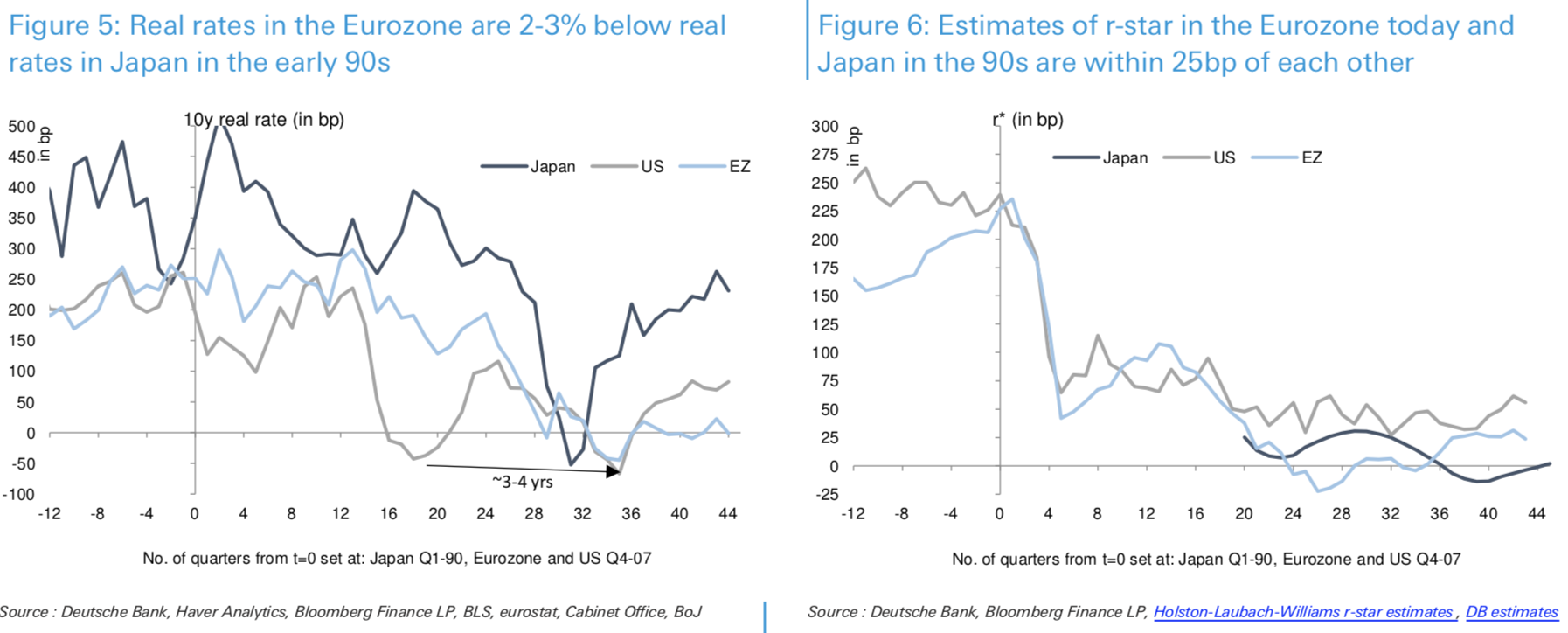

Dahinter steht aus Sicht der Bank auch eine andere Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit und -konsequenz der Geldpolitik: “To measure the effectiveness of monetary policy in supporting the deleveraging process, we focus on the 10y real rate and the real effective exchange rate. In Japan, 10y real rates stayed in a 2-3% range. In contrast, 10y real rates in the US declined by 300bp relative to pre-crisis and went negative to -50bp after operation twist in late 2011. In Europe, 10y GDP weighted real rates also went negativewith the announcement of QE in 2015. Thus, similar to the credit dynamics, the policy response in Europe lagged the US by 3-4 years (left graph below). The 300bp difference in real rates between Japan in the 90s and Europe is significant given that estimates of neutral real rates are within 25bp of each other (right graph below).” – bto: Mario Draghi hätte so – spät aber, immerhin – das Japan-Szenario verhindert.

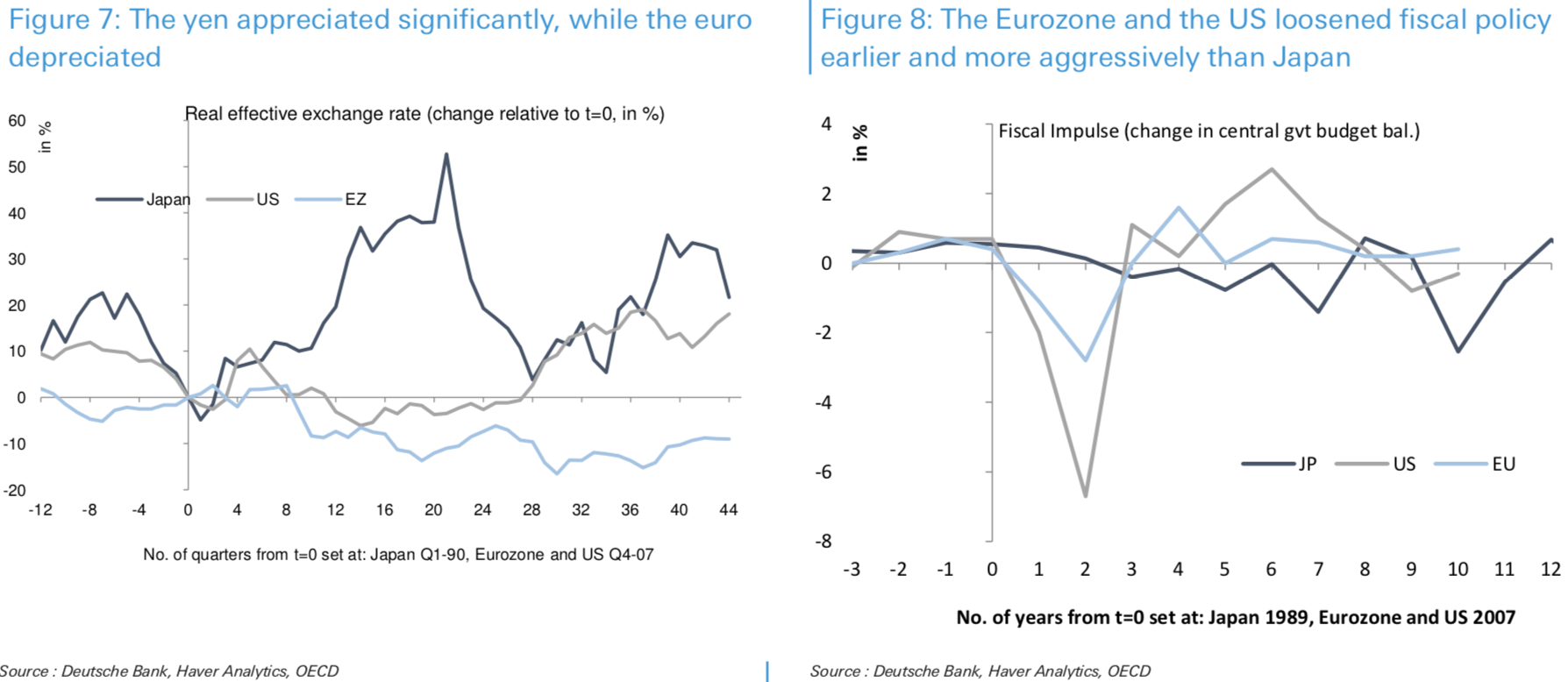

Dann zu einem deutlichen Unterschied, dem Wechselkurs, der übrigens auch das heute Morgen schon gesehene Exportwachstum in Europa versus Japan erklärt: “Japan had to suffer a significant appreciation in its currency with a peak 50% appreciation of the yen on a real effective exchange rate (REER) basis. In contrast, the euro depreciated by more than 15% in 2015, vs. a trough for the USD REER of -6% (left graph below).” – bto: Japan gelang es damals nicht, die Krise “zu exportieren”, uns in gewissem Umfang schon, wobei davon vor allem Deutschland profitiert hat!

Und auch die Fiskalpolitik hat besser und schneller reagiert, meinen die Analysten der Deutschen Bank: “Initially, fiscal policy in the Eurozone was very reactive (as it was in the US), which accommodated the private sector deleveraging . However, the Eurozone crisis resulted in a sharp fiscal tightening. The same occurred in the US following the debt ceiling issues, but the adjustment of the private sector was already well advanced by then and monetary policy was more aggressive. Japan was slower to loosen fiscal policy.” – bto: Auch das leuchtet ein, ist allerdings eine Politik, die auf weiter steigende Schulden setzt. Das muss sie allerdings ohnehin, wie ich immer wieder bei bto diskutiere.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

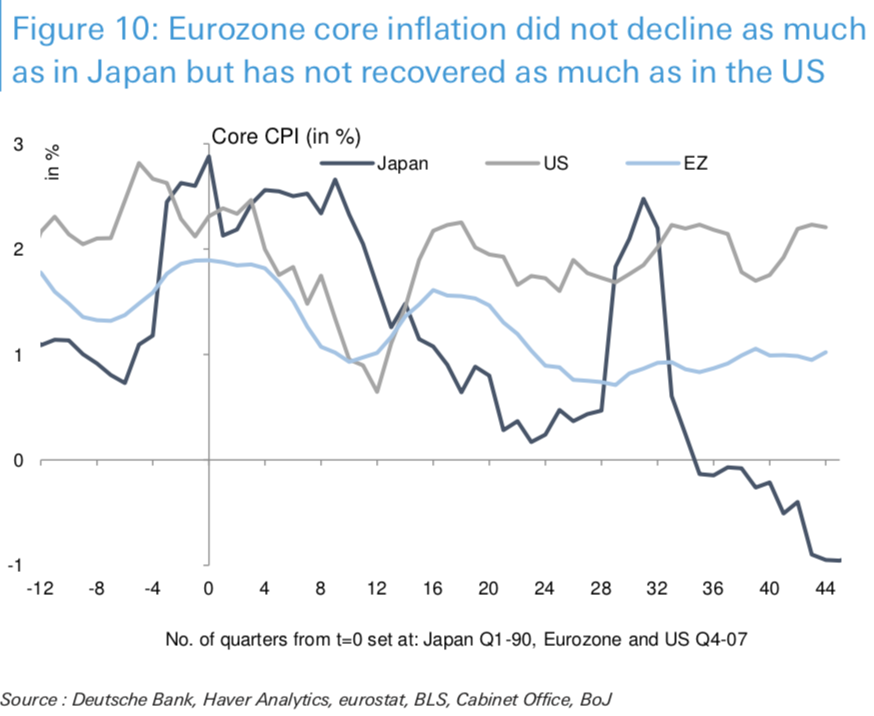

“In Japan, core inflation initially held up, which is consistent with a delayed economic adjustment. However, after 3 years it started a downward trend which was only briefly interrupted by the 1997 VAT hike. In the US and Europe core inflation initially declined before bouncing back to 1.5-2%. Following the debt ceiling episode, euro-zone crisis and supply shock to oil prices, core inflation declined in both the US and Europe. The scale of the decline in Europe was larger and the recovery in US core inflation has been more pronounced. The behaviour of Europe’s inflation is markedly better than Japan. However, so far, its performance is worse than simply lagging the US.” – bto: Das könnte bedeuten, dass es eben in Europa doch in Richtung des japanischen Szenarios geht. Ohnehin dürfte es zu früh sein, eine Entwarnung zu geben.

Quelle: Deutsche Bank

So kommen die Analysten zunächst zu einem positiven Fazit. Nämlich dem, dass die Schuldenblase – und damit der Druck zur Entschuldung – kleiner war in Europa als in Japan, dass die Politik besser reagiert hat und die Inflationsraten immer noch höher liegen. Andererseits sehen sie auch Risiken: “(…) in an imperfect union, Europe’s weakest link (Italy) will matter. Italy does share more similarities with Japan than the rest of Europe. For instance, its real rates have remained close to Japanese levels, while arguably its neutral real rate is even lower. Second, the exposure of Europe to global growth will make it more sensitive to other large economies.” – bto: Der entscheidende (positive) Unterschied sind die Exporte, die neben dem Wechselkurseffekt vor allem auf die schuldenfinanzierte Konjunktur in China zurückgeführt werden können.

China sehen sie ähnlich vorsichtig wie ich: “In that context, China does share troubling similarities with Japan. Credit growth is higher than the levels observed in Japan in the early 90s and itsreal effective exchange ratehas appreciated significantly as it did in Japan. Could China more resemble Japan than Europe on this measure?” – bto: Und die demografische Entwicklung ist schlechter als in Europa. Deshalb ist China ein Risiko für Europa und vor allem Deutschland.

Damit bleibt eigentlich die skeptische Sicht valide. Teile der Eurozone sind wie Japan. Andere Teile sind es (noch) nicht, weil sie von einem anderen Ponzi-Schema abhängen (China) und eine Sonderkonjunktur erlebt haben. Nun kommt diese an ihr Ende und die politischen Spannungen werden zunehmen. Ist es in Japan die Allokation des Schadens innerhalb einer Gesellschaft, ist es bei uns die Allokation zwischen Gesellschaften. Das dürfte die Euro-Zone nicht ohne Weiteres überstehen.

Leider kann ich die Studie nicht verlinken.