Doch eine säkulare Stagnation?

Die säkulare Stagnation wird wieder Thema, jetzt, wo sich die Weltwirtschaft doch nicht so gut entwickelt, wie noch vor wenigen Monaten erwartet und erhofft. bto hat das Thema immer wieder kritisch beleuchtet:

→ „30 Jahre Stagnation der Weltwirtschaft“

→ Säkulare Stagnation – à la Eiszeit – wirklich das Problem?

→ „Unsinn über die säkulare Stagnation“

Nun fragt Martin Sandbu in der FINANCIAL TIMES (FT): “How secular is secular stagnation?” Eine berechtigte Frage. Denn nur weil wir – bei schrumpfender Erwerbsbevölkerung, stagnierenden Produktivitätsfortschritte und enormen Schuldenlasten – weniger schnell wachsen als früher, ist “säkular” eine ziemlich steile These. Wir könnten an allen drei negativen Punkten etwas ändern! Nun schauen wir mal auf die Argumentation:

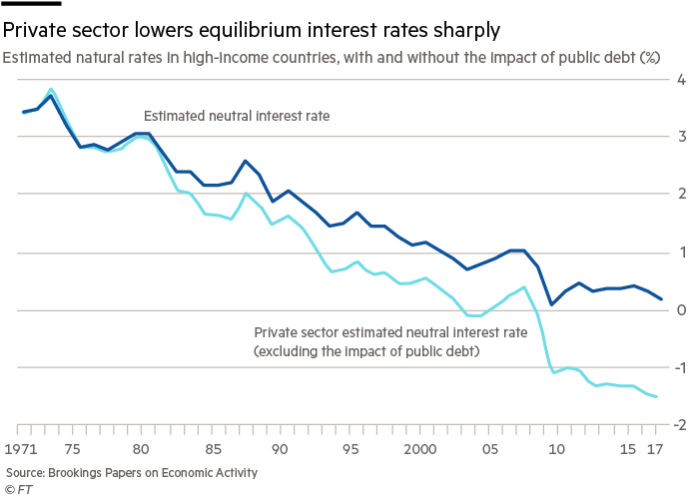

- “(…) Lawrence Summers further developed his thesis that rich economies are in the grip of ‘secular stagnation’. In an article, Summers and Lukasz Rachel develop new estimates of the “natural” rate of interest — the interest rate that brings desired savings and desired investment in the economy into balance — and find that it has fallen by about 3 percentage points over the last generation.” – bto: hier der Link zu dem Artikel → “On Falling Neutral Real Rates, Fiscal Policy, and the Risk of Secular Stagnation”. Ich finde es immer wieder interessant, dass für Summers die Verschuldung nie ein Problem ist, sondern immer nur das gestiegene Kapitalangebot durch Sparen.

Martin Wolf kommentiert ebenfalls in der FT die Studie und von dort nehmen wir zur Illustration ein paar Bilder (die einfach schöner sind, als in dem Paper von Brookings). Zunächst der Rückgang der Zinsen seit 1980. Bekannt, aber immer wieder beeindruckend anzuschauen:

Quelle: FT

- “More astonishing, they point out that several public policy decisions (such as higher government debt) has counteracted this fall, and that without them, the ‘private’ real natural rate of interest would have fallen by as much as 7 percentage points.” – bto: Das ist die Badewannen-Theorie in extrem. Wir haben einen sehr großen Überhang an Ersparnis und deshalb müssen wir tiefe Zinsen haben. Wenn man aber davon ausgeht, dass Geld geschaffen wird durch steigende Verschuldung und wir diese Verschuldung unproduktiv verwenden, muss es doch zu einer “säkularen Stagnation” kommen!

Quelle: FT

- “The most consequential question, however, is what it means for policy. Summers’s secular stagnation analysis is that equilibrium rates have come so far down that it is impossible for central bank or market interest rates to make demand match the level of potential supply, leaving the economy indefinitely underemployed. To get out of stagnation, other sources of demand have to be increased, where Summers often points to fiscal policy. (…) if the asset-wealthy are less likely to spend out of income than the asset-poor, then a net wealth tax (…) could be implemented so as to lift aggregate demand.” – bto: Beide Empfehlungen sind vorhersehbar. Doch was ist mit der andere Seite der Medaille, der zunehmenden Verschuldung?

Sandbu zweifelt auch an dem Nutzen der Theorie der säkularen Stagnation und bringt drei Argumente:

- “First, it may lead to policy cures that are worse than the disease. If demand is chronically too low, it is not just fiscal policy that can address this; so can a mercantilist trade policy aimed at boosting net exports. Secular stagnation quickly becomes a justification for the Trumpian fetish of seeing exporting as strength and importing as weakness, and all the bad policies such a view brings with it.” – bto: Ja, man kämpft um Nachfrage und Länder wie Deutschland machen sich unbeliebt.

- “Second, I am unconvinced that monetary policy cannot do more . The ‘zero lower bound’ is clearly not at zero since several central banks have lowered short-term rates below it. The idea of an ‘effective’ lower bound somewhere below, but allegedly close to, zero is a theoretical construct. Nobody has seen any sign of it, which means there is at least some further way to go for conventional policy. (…) With the 10-year Treasury yield near 3 per cent, the US economy is far from any lower bound, if one exists.” – bto: Es werden bereits Maßnahmen diskutiert wie Bargeldsteuer etc., um die Politik auch im negativen Bereich fortsetzen zu können.

- “Third, we must avoid confusing between stocks and flows. The arguments about chronically weak demand are ‘stock’ arguments — reasons why the level of aggregate demand is lower, and has stayed lower, than the level of supply for surprisingly long. Economic growth, however, is a matter of changes in the levels of demand and supply. A low level of demand is perfectly compatible with steady-state solid growth in which all the components of demand change by the same percentage every year. And it is not clear how secular stagnation arguments that explain why the level is low also act as arguments for why growth should be low.” – bto: Das bedeutet auch, dass man mit anderen Instrumenten ebenfalls eine Verbesserung erzielen könnte.

- “There are equilibrating mechanisms when the level of demand is below that of supply for some time. If it subdues price growth — and it seems to have done so — it will make for a greater real money supply over time, which should push up demand. But this could take time. Alternatively, inadequate demand levels may inhibit investment and employment, which reduces the level of supply capacity permanently (…) My own chief worry is that policymakers mistakenly take the “secular” part of stagnation so seriously that they snuff out any sign that demand is catching up with supply.” – bto: Und was würde dann passieren? Es gäbe Inflation. Wie schön wäre das aus Sicht der Politiker, endlich gäbe es Hoffnung, die Schulden doch noch zu entwerten.

→ ft.com (Anmeldung erforderlich): “How secular is secular stagnation?”, 13. März 2019

→ ft.com (Anmeldung erforderlich): “Monetary policy has run its course”, 12. März 2019