Die Schuldendroge verstärkt Ungleichheit und Krisen

bto ist ein Schulden-Blog. Im Kern dreht es sich immer um das gleiche Grundübel: die zunehmende Abhängigkeit der Weltwirtschaft von immer schneller steigender Verschuldung, mit allen damit im Zusammenhang stehenden Problemen: von der wachstumshemmenden Zombifizierung, über steigende Ungleichheit der Vermögensverteilung, bis hin zur immer rascheren Abfolge von Blasen an den Finanzmärkten.

Nun muss man nicht bto lesen, um diese Probleme zu erfassen. Es genügt, die FINANCIAL TIMES (FT) von Zeit zu Zeit in die Hand zu nehmen. Was viel zu wenige hier tun. Auch nicht die Professoren der Wirtschaftswissenschaften, so mein Eindruck. Täten sie es nämlich, würden sie nicht so sehr in ihren theoretischen Modellen verhalten und vor allem könnten sie die Politik besser beraten. Denn was wir aus deutscher Sicht vorführen; ist meines Erachtens nur zu verstehen, wenn man davon ausgeht, dass Politik und Berater keinen blassen Schimmer von finanziellen Transaktionen haben. Andererseits wird unser Finanzminister ja von einem ehemaligen Top-Manager von GoldmanSachs beraten. Was mich noch mehr wundern lässt. Oder auch nicht.

Werfen wir einen Blick auf zwei Beiträge in der FT zum Thema Schulden im letzten Monat. Zunächst Martin Wolf:

- “Debt creates fragility. The question is how to escape from the trap. To answer it, we need to analyse why today’s global economy has become so debt-dependent. That did not happen because of the idle whims of central bankers, as many suppose. It happened because of an excessive desire to save relative to investment opportunities. This has suppressed real interest rates and made demand far too reliant on debt.” – bto: Wolf ist hier zunächst mal im Camp der Badewannentheoretiker, die einen Ersparnisüberschuss verantwortlich machen für die sinkenden Zinsen und damit für die steigende Verschuldung. Das Argument würde ich nicht verwerfen, ich würde aber durchaus die Rolle der Notenbanken nicht so abwehren, wie er es tut. Das klare Signal, immer rettend einzugreifen und es auch zu tun, muss einen starken Anreiz geben, mit Kredit zu arbeiten.

- “Two recent papers illuminate both the forces driving this rise in leverage and its consequences. (…) (One) on ‘Indebted Demand’, explains how debt overhangs weaken demand and lower interest rates, in a feedback loop. (….) beyond a point, inequality weakens an economy by driving policymakers into a ruinous choice between high unemployment or ever-rising debt.” – bto: Dahinter steht der Punkt, dass hohe Schulden als solches zu geringerem Wachstum führen – Zombifizierung, vorgezogene Nachfrage, …. – und deshalb immer mehr stimuliert wird, um die Wirtschaft doch zu beleben, was wiederum höhere Schulden bedeutet.

- “The ‘The Saving Glut of the Rich and the Rise in Household Debt’ paper (…) makes two points. First, rising inequality in the US has resulted in a large increase in the savings of the top 1 per cent of the income distribution, not matched by a rise in investment. Instead, the investment rate has been falling, despite declining real interest rates. The rising savings surplus of the rich has been matched by the rising dissaving, or consumption above income, of the bottom 90 per cent of the income distribution.” – bto: Auch hier würde ich intuitiv zustimmen. Es ist aber eben nur ein Aspekt. Es hängt alles zusammen.

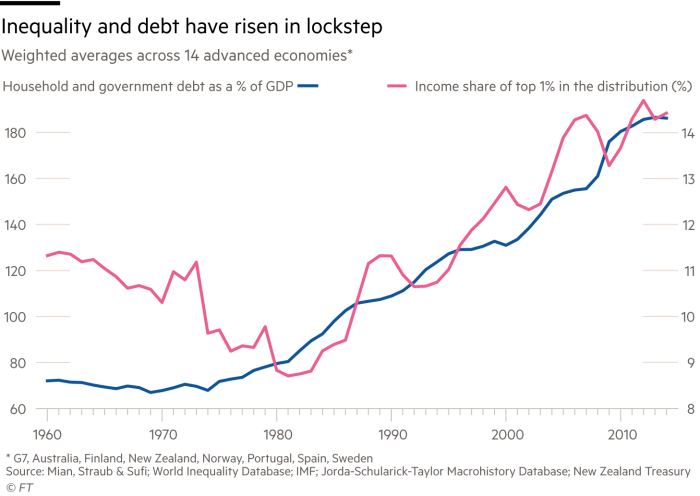

- “There is a clear link between the saving of the rich and dissaving of the less rich, and the accumulation of credit and debt. (…) The rich hold claims on the less rich, not only directly, via bank deposits, but via equity holdings in businesses that also hold such claims. This phenomenon of rising household debt and rising inequality is not unique to the US.” – bto: Nicht bei uns, dafür leben wir von der zunehmenden Verschuldung unserer Kunden im Ausland.

- “Why does the rising debt matter? One answer (…) is that the economy becomes increasingly driven by finance and fragile, as borrowers become ever more overburdened. Another is the idea of ‘indebted demand’ (…) As debt soars, people are ever more unwilling to borrow still larger amounts. So interest rates have to fall, to balance supply with demand and avoid a deep slump. (….) This is one mechanism driving what Lawrence Summers has called ‘secular stagnation’.” – bto: Hier werden die Schulden immer als Folge beschrieben, die dann weitere schlechte Folgen haben (eine Sicht, die ich bekanntlich teile) und nicht als Ausgangspunkt. Ich würde sie aber als Ausgangspunkt der Entwicklung sehen.

- “So, how are we to escape from the debt trap? One step is to diminish the incentive to finance businesses with debt, rather than equity. The obvious way to do so is to eliminate the preference of the former over the latter in almost all tax systems. (…) In addition, we have a huge opportunity now to replace government lending to companies in the Covid-19 crisis with equity purchases. Indeed, at current ultra-low interest rates, governments could create instantaneous sovereign wealth funds very cheaply.” – bto: Das ist ein interessanter Gedanke. Ich denke auch, dass es vor allem steuerlich attraktiver werden muss, mit Eigenkapital zu arbeiten. Allerdings dürfte der Umstieg mit erheblichen Wertverlusten auf den Vermögensmärkten einhergehen. Wie der zu gestalten wäre, ist mir nicht ganz klar.

- “Yet none of this would fix the ongoing dependence of macroeconomic stability on ever more debt. There are two apparent solutions. The first is for governments to keep on borrowing. But, in the very long term, this is likely to lead to some sort of default. The well-off, who are the principal creditors of government, are bound to bear much of the costs, in one way or the other. The alternative is to shift the distribution of income, in order to create more sustainable demand and so stronger investment, without soaring household debt. (…) Ever-rising household and government debt will not stabilise the world economy forever. Nor should asset-price bubbles remain so central to our economy. We will have to adopt more radical alternatives. A crisis is a superb a time to change course. Let us start right now.” – bto: Wolf sieht also in Umverteilung die Lösung, man könnte auch sagen in einer Form von “Back to Mesopotamia”, also einem Schulden-Vermögensschnitt. Dies ist in sich konsequent und auch eine Idee, die mir nicht fernliegt. Problem ist allerdings die Umsetzung, vor allem innerhalb einer Währungsunion.

Was mir nicht gefällt an der Argumentation von Wolf ist die Rolle der Schulden. Sie sind für ihn einfach nur die Folge, während ich nach wie vor denke, dass es politisch gewollt war und deshalb die Schulden die Vermögen treiben. Ein Zusammenhang, den ich schon in Die Schulden im 21. Jahrhunderterläutert habe.

Martin Sandbu von der FT sieht das ähnlich:

- “My concerns are somewhat different. The causal relationship also runs from debt to inequality. The rapid liberalisation of finance from the 1980s was a significant cause of credit and debt growth, which in turn fuelled both asset price inflation and a greater need for people to indebt themselves to own a house. Much of the increase in inequality came from higher rental or capital incomes. Increased financial intermediation also led gross debt to increase more than sectoral net indebtedness. These mechanisms explain why, for example, gross cross-border debt grew much faster than what the changes in macroeconomic savings rates can account for.” – bto: Das sind ganz entscheidende Punkte. Hinzu kommt noch die Möglichkeit, höhere Assetpreise erneut höher zu beleihen. Der Leverage-Effekt verstärkt die Entwicklung.

Quelle: FT

- “I also think the macroeconomic demand effects of high debt levels are unclear, since the burden of debt service has developed in a much more benign way than the amount of debt outstanding (because of falling interest rates). (…) On average, debt service takes up less of households’ incomes than at any time since 1980.” – bto: Das ist ja auch die Argumentation jener, die in höheren Schulden der Staaten kein Problem sehen.

- “Even if average debt service is low, large debt balances make for fragility. That is because when debts are large relative to economic activity, a smaller proportionate change in economic prospects suffices to cause cascading insolvencies, with all their legal and economic repercussions.” – bto: Simpler gesagt, es kommt leichter zu einer deflationären Spirale.

- “(…) a debt overhang hinders investment in otherwise productive activities (a cause of slow supply growth rather than insufficient demand), because potential investors fear their money will just go to cover legacy debts. (…) it hinders mobility of both workers and capital, geographically and to more profitable jobs and sectors (again a supply-side problem).” – bto: Und es fördert Zombifizierung.

- “As we think about how to rebuild our economies better, we must try to reinvent the financial system so that savings can finance investments without excessive debt accumulating. That requires tackling debts from the past, the debts now being incurred at a dizzying pace in response to the Covid-19 lockdowns and the debt accumulation likely to continue in the future if we do not change our financial system.” – bto: Und da sind wir bei den Gedanken der Endlagerung bei der EZB und der Umstellung auf Vollgeld – dem sogenannten Chicago-Plan.

- “The overarching principle in tackling all three must be to make financial relationships more equity-like. It is not the amount of financing in the economy that is the problem, but that so much of this financing is in the form of debt.” – bto: Das setzt aber auch voraus, dass man die Konsequenzen schlechter Investments zulässt: Pleiten.

- “For the legacy debts that already exist, giving them the characteristics of equity essentially means making it easier to restructure them. This will undoubtedly be necessary given the huge hit to national income from the lockdown. In the household and non-financial corporate sector, such restructuring takes place through bankruptcy processes.” – bto: den man dann aber auch durchziehen muss, sodass die Aktionäre der Unternehmen, die mit zu hoher Verschuldung gearbeitet haben, auch verlieren.

- “(…) some types of debt may need special treatment. Governments should remember that the resolution regimes for banks brought in after the crisis, which require a restructuring of their debts before any recapitalisation with taxpayer money, are there to be used.” – bto: Das schreibt sich leicht, ist aber politisch nicht umsetzbar. Das kann man in Italien beobachten, wo es seit Jahren nicht gemacht wird.

“What to do with highly indebted governments is the biggest question of all (…).” – bto: und die am schwersten zu beantwortende Frage. Es kann nur über die Notenbanken gehen.