Die Gründe für sinkende Realzinsen

Die Zinsentwicklung war und ist Thema bei bto:

→ Säkulare Stagnation als Grund für tiefe Zinsen?

→ Zinsen hoch oder runter – was kommt?

→ Doch Freispruch für die Notenbanken?

→ Niedrigzinsen aus Mangel an sicheren Anlagen in überschuldeter Welt

→ „Tiefe Zinsen bis der Ketchup spritzt“

→ Niedrigzinsen: Die Badewannen-Theorie springt zu kurz

→ Warum sind die Zinsen so tief?

Nun also eine Studie, die schon im letzten November erschien und auch in den Medien aufgegriffen wurde. Sie beleuchtet nicht viele neue Aspekte, ist aber eine ganz solide Zusammenfassung und ist deshalb eine gute thematische Auffrischung sein. Hier also die Highlights der Studie vom Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft in Köln (IW):

- “Whether the current low interest rate environment is based on a falling trend or based on a cycle with the chance of a recovery (…) needs a more rigorous statistical analysis. Therefore, we first identify the drivers of real interest rates and use a panel data regression model to test whether they are predictive of the evolution of real interest rates. We then use forecasts of the drivers of real interest rates to identify whether there is a persistent trend or a mean-reverting behaviour in real interest rates.” – bto: Ich erinnere in diesem Zusammenhang an die Studie der Bank of England, die zeigt, dass es auch früher schon lange Phasen sehr tiefer Zinsen gab, die alle endeten: durch einen externen Schock und dann dramatisch: → Die Lehren aus 700 Jahren Zins-Geschichte. Deshalb ist es richtig, bei den Treibern anzusetzen, wenn man sie denn identifizieren kann.

Dann fassen sie – ganz praktisch – noch mal die Theorien zum Thema zusammen:

- The global savings glut hypothesis states that there is a global excess of desired savings over desired investment, which puts a downward pressure on real interest rates. A large part of the huge savings come from China and other emerging market economies in Asia, as well as from oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia. (…) The global savings glut hypothesis predicts that interest rates will stay low for a longer period because of the persistency of the drivers of real interest rates.” – bto: Ich nannte das mal Badewannen-Theorie. Mir fällt nur schwer, daran zu glauben in einer Welt, in der das Bankensystem für Geldschaffen steht. Meine These wäre da umgekehrt: Wenn jemand zu viel Geld schafft = Schulden macht, muss Geld immer billiger werden.

- “The secular stagnation hypothesis predicts low interest rates due to low investment, which is caused by a declining population growth, a reduced capital intensity and a falling relative price of capital goods. Similar to the global savings glut hypothesis, the secular stagnation hypothesis predicts that real interest rates will stay low for a longer period because of the persistency of the underlying drivers of real interest rates.” – bto: ist einfach sehr ähnlich, es hat nur eine klarere Begründung für das Spar- und Investitionsverhalten.

- “The safe asset shortage hypothesis sees a growing gap between the supply of safe assets and the demand for safe assets. (…) In the view of the authors, the growing demand for safe assets and the limited supply of safe assets made it possible for countries like Italy and Greece to issue their government debt at favourable conditions. Moreover, it facilitated the possibility to issue mortgage-backed securities. After the global financial crisis and the banking and sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone, these assets were no longer regarded as safe assets, making the safe asset shortage more severe. This de-pressed the yields on safe assets even more.” – bto: Klingt wie eine Unterversion der beiden anderen. Ich denke, es wäre dann die Folge der Erkenntnis des Marktes, dass wir es mit immer fauleren Schulden zu tun haben und letztlich auch die Wirkung davon, dass zu viel Geld geschafft wird.

- “Demographic factors, e.g. increasing life expectancy, (…) requires a higher savings rate in order to maintain old-age consumption. (…) The lower population growth slows the growth rate of the capital stock, which decreases the necessity for investments. Thus, on the aggregate level, savings should grow faster than investment (…)” – bto: Das klingt wie eine weitere Untervariante der Badewannentheorie: mehr Angebot, weniger Nachfrage.

- “Investments in intangible assets (…) require lower investment costs compared to investments in tangible assets, e.g. machinery and buildings. (…) A shift from tangible investment to intangible investment would imply a slower growth rate of desired investment over desired savings, which would lead to downward pressure on real interest rates.” – bto: also noch mal das Gleiche, nur jetzt von der Nachfrageseite.

Fazit bto: Alle arbeiten mit Modellen von Angebot und Nachfrage nach Geld. Keiner bringt hier unser Geldsystem ins Spiel und niemand benennt die Schulden als Ursache und Folge. Dabei würde es sich lohnen, auch dorthin zu schauen. Viele Schulden erhöhen das Geldangebot und senken so den Zins und machen umgekehrt noch tiefere Zinsen nötig, um tragbar zu sein. Na ja, Modelle zu bauen ist noch nicht machbar bei bto, aber das wäre mal eine Studie wert.

Doch nun zurück zum IW:

Die Forscher schauen zunächst, ob die Sparneigung zugenommen hat. Die Zahlen zeigen das etwas. Aber nun nicht wirklich so, dass man einen Haken dran machen könnte. Deshalb schauen die Forscher auf die (theoretischen Treiber) höherer Sparneigung: Demografie, Lebenserwartung, Belastung durch Kosten für höheren Anteil älterer Menschen. Dann schauen sie auf die Entwicklung der Kapitalnachfrage: Investitionen von Staaten und Unternehmen, Entwicklung der Erwerbsbevölkerung. Wenn man sich die Bilder anschaut, kann man ehrlich gesagt noch nicht den Trend identifizieren, der wirklich die Zinsentwicklung erklärt.

Auch deshalb bauen die Forscher des IW ein ökonometrisches Modell, um die Wirkung der einzelnen Variablen zu quantifizieren und damit zu einem Vorsagemodell zu kommen:

- “(…) we estimated three equations: one for the real interest rate, one for savings and one for investment. After we have interpreted the coefficients and determined the plausibility of the models, we use them to determine interest rate misalignments and to forecast future real interest rates.” – bto: Wenn ich die Vergangenheit erklären kann, sollte ich in der Lage sein, die Zukunft zu modellieren.

- “The panel dataset ranges from 1990 to 2016 and covers 24 OECD countries. The time series are the long-term real interest rate, savings and investment in percent of GDP, population growth, the growth rate of the labour force, the growth rate of GDP, life expectancy, the young age and the old age dependency ratios, the public deficit and the net capital outflow. A second dataset with data on the age of capital stock, labour productivity and total factor productivity, and cap- ital intensity is also available for the years 1990 to 2015.” – bto: also alle Inputfaktoren, die in den verschiedenen Theorien genannt werden.

Das führt zu folgenden Erkenntnissen:

- “(…) lower interest rates do not cause savings to fall, they lead to a higher investment. One reason for the missing interest rate sensitivity of savings might be that for households’ intertemporalconsumption decision-making, the rate of return is less important compared to the growth of their income as measured by GDP growth here, which seems to be the major determinant of savings. In contrast to this, investment decisions seem to be more interest rate sensitive, since the successful implementation of investments depends on the financing conditions.” – bto: Es überrascht nicht, nur, dass Investitionen hochgehen, nur ein bisschen, investieren wir doch nicht wirklich in der heutigen Zeit, trotz billigem Geldes. Mehr in Aktienrückkäufe und M&A.

- “(…) we find a negative and statistically significant relationship between the public deficit and the real interest rate. Moreover, we find a positive and statistically significant relationship between the public deficit and private investment. This positive relationship is in contrast to the loanable funds model’s predictions and it may be due to complementarities between public and private investment not covered in the model. Public investment in public infrastructure, like broadband internet, enables private companies to increase their investment, which can rationalise the positive coefficient. The complementarities between public and private investment are emphasized in the discussion about secular stagnation, so the regression model results support the secular stagnation hypothesis.” – bto: was übrigens ebenfalls für Deutschland relevant ist. Die geringen Investitionen des Staates führen auch zu geringen Investitionen der Unternehmen und verstärken so den Kapitalexport und die Handelsüberschüsse.

- “In a growing economy, the increasing incomes enable higher savings, while companies are more confident in their investment decisions if the economy is performing. (…) we find for savings as well as for investment positive and statistically significant coefficients, with a higher coefficient for savings.” – bto: Das Modell zeigt also, dass Sparen und Investitionen von hohem Wachstum profitieren. Das passt.

- “Every additional year of life expectancy decreases the real interest rate by 1.036 percentage points. Although this effect seems to be very high, one can see in the data that life expectancy increased by 5.7 years from 1990 to 2016, while the real interest rate fell by 4.1 percentage points. (…) We also find a positive coefficient for savings. However, the estimate is not statistically significant. Nonetheless, we find that a higher life expectancy leads to lower investment.” – bto: Nun muss man natürlich wissen, dass der Zeitraum, der hier betrachtet wird, auch jener ist, in dem die Schulden weltweit explodiert sind. Insofern gilt natürlich, dass eine Korrelation noch keine Kausalität sein muss.

- “The growth rate of the labour force should be positively linked to savings and investment, because a higher growth rate of the labour force indicates a stronger economy. (…) The estimated regression models indicate a negative coefficient for the real interest rate and positive coefficients for savings and investment. All coefficients are statistically significant. Moreover, the effect on savings is higher than the effect on investment.” – bto: was intuitiv auch einleuchtet, weil die Unternehmen bei wachsender Erwerbsbevölkerung zwar auch mehr Nachfrage sehen, zugleich aber auch mehr Arbeit durch Menschen erfüllen können.

- “The old age dependency ratio and the young age dependency ratio describe the composition of young and old people in relation to the labour force. Since young and old people have lower savings rates than the labour force, a smaller dependency ratio means a higher savings rate. The baby boomers have contributed to the fall in the dependency ratios and thereby to the increase in the savings rates. The effect of the retirement of the baby boomers depends on how much they reduce their savings rates. We find negative and statistically significant effects of the two dependency ratios on investment. Moreover, the effect of the dependency ratios on the real interest rates is negative, but only statistically significant for the young age dependency ratio. Thus, when the ratio of young people to the labour force decreases by one percentage point, real interest rates rise by 0.485 percentage points.” – bto: Weniger Kinder führen zu höheren Zinsen?

- “(…) we do not find that the slowdown of productivity has contributed to lower interest rates. In the regression model, the coefficient that ties total factor productivity to the real interest rate is not statistically significant. The same result applies when we use labour productivity instead. However, we find that the growth in total factor productivity is associated with a decline in the investment rate, while it does not show any statistically significant effect on savings. The negative effect between the investment rate and total factor productivity is surprising, because technological progress should normally lead to more profitable investment opportunities.” – bto: oder aber zur natürlichen Reaktion der Unternehmen, Gewinne aus bestehender Technologie noch solange wie möglich zu nutzen?

Nun, wo sie ein Modell haben, machen sich die Forscher an die Projektion:

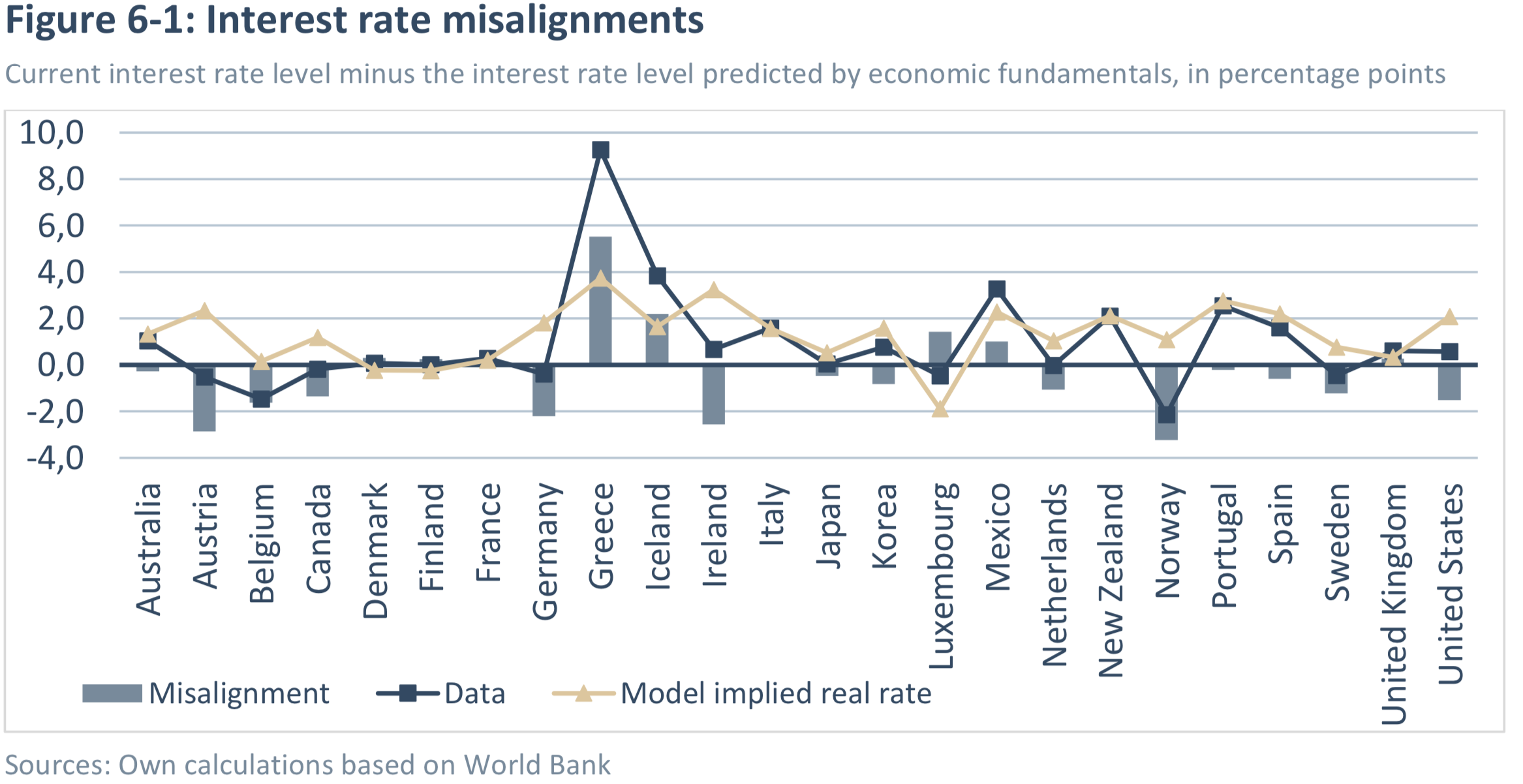

- “The regression model for the real interest rate can be used to calculate the real interest rate that is determined by economic fundamentals. This model-implied interest rate can then be compared to the data in order to detect misalignments. The detection of misalignments is important for our forecasting exercise..” – bto: Jetzt schauen wir uns an, welche Zinsen das Modell vorhersagt und wo die Zinsen wirklich sind. Abweichungen müssten sich dann korrigieren:

- “In Austria, Germany, Ireland and Norway, interest rates are more than two percentage points lower than indicated by the model. One reason may be the accommodative monetary policies in these countries. Although the United States are also characterized by excessively low interest rates compared to the model predictions, the misalignments are smaller, in part because the Federal Reserve Bank has already started its interest rate normalisation policy.” – bto: Frankreich, Italien, Spanien passen und Griechenland natürlich auch, modellieren wir doch ohne jeglichen Bezug zu Schuldenständen. Damit unterstützt die Analyse nur, was wir alle wissen, nämlich, dass das Geld für Deutschland zu billig ist.

- Dann kommen sie zur Prognose für die kommenden Jahrzehnte: “For Germany, we find a rebound from currently -0.4 percent to 1.3 percent by 2025 due to the elimination of the misalignment when the ECB starts to normalise its monetary policy. After the normalisation of this interest rate cycle, the negative trend in the real interest rates goes on, leading to a real interest rate of 0.5 percent in 2035 and a real interest rate of 0.0 percent in 2050.” – bto: “nachdem die EZB ihre Geldpolitik normalisiert”?? Selten so gelacht. Wissen wir doch, dass die EZB gar nicht anders kann und wir in der nächsten Rezession erst so richtig nach unten gehen.

- Doch das wissen auch die Autoren, denn sie schließen: “As interest rates are close to zero or even negative, classical monetary policy faces limits. Therefore, alternative measures – like quantitative easing – will become more common. The current monetary policy, consequently, will not be an exception but rather the forerunner of a change in monetary policy.” – bto: Und damit könnte sie dazu beitragen, Geld noch billiger zu machen.

Ich denke, es lohnt sich, neue Modelle aufzubauen. Ich denke, wer sich in eigener Währung verschuldet, senkt mit zunehmender Verschuldung (= Schaffung von Geld) das Zinsniveau.

→ IW: “Reasons for the Declining Real Interest Rates”, 28. November 2018