Der Fehler der Notenbanken ist längst gemacht

John Hussman habe ich an dieser Stelle schon mehrfach zitiert. Er ist seit langem ein Skeptiker der Geldpolitik und vor allem der Bewertungen an den Märkten. In einem Gastbeitrag für die FT macht er in knappen Worten klar, wie groß der Fehler der FED in der Vergangenheit war und der sich jetzt sichtbar zeigt:

- „The stock market has been jolted from its record highs in recent weeks, as investors who rely on low interest rates to “justify” steep valuations have been confronted with the prospect of tighter monetary policy.“ – bto: das kennen wir aus der Diskussion unter anderem in meinem Sonderpodcast vor einigen Tagen. Wenn alles an billigem Geld hängt, wird es ungemütlich.

- „The US Federal Reserve appears to be walking a tightrope, with the potential for a policy error at each side. On one side, US consumer price inflation reached an annual rate of 7.1 per cent in December, and the central bank appears behind the curve to contain it (…) On the other side, the inflation spike has emerged at the same time as supply disruptions, a gradual narrowing of pandemic-related fiscal deficits and indications of weaker business activity.“ – bto: richtig, es kann durchaus sein, dass die Wirtschaft schwächer ist als man denkt. Nur wissen wir auch, dass billiges Geld in einem Umfeld hoher Schulden nur verhindert, nicht treibt.

- “This leaves the Fed at risk of tightening policy into a slowing economy. Yet these risks may be minor compared with the policy error the Fed has already made, by abandoning a systematic policy frameworkfor more than a decade, in favour of a purely discretionary one.“ – bto: das gilt auch für die EZB. Das Problem ist früher entstanden. Und es wird sich weiter verschärfen in den kommenden Jahren. Einfach, weil Schulden und Vermögenspreis-Abhängigkeit es erzwingen.

- „“Systematic,” in this context, means a framework where policy tools such as the level of the fed funds rate maintain a reasonably stable and predictable relationship with observable economic data such as inflation, employment, and the “output gap” between real gross domestic product and its estimated full-employment potential.“ – bto: das kann den Notenbanken natürlich nicht gefallen, denn dann haben sie nicht mehr die Möglichkeit sich als “Retter” zu inzinieren.

- Denn: “(…) purely discretionary policy is like inconsistent parenting; having set no boundaries, any failure to appease is met with wails of surprise, crisis and tantrum.“ – bto: und vor allem dem Erpressungsrisiko, dass man unter dem Eindruck einer akuten Krise wieder helfen muss.

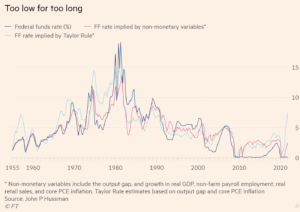

- „In 1993, Stanford economist John Taylor proposed a systematic framework for assessing what the fed funds rate should be based on the level of inflation and the output gap. The Taylor Rule and related guidelines mirror the actual fed funds rate reasonably well from 1950 until 2003. The similarity weakens after 2003, and particularly after 2009 owing to shifts in the Fed’s monetary policy.“ – bto: einfach weil die Stabilität des Finanzsystems wichtiger war als die Realwirtschaft.

Quelle: FT

- „Ultimately, the Fed’s central policy error may have little to do with the speed at which it tapers its asset purchases, or the timing of the next few rate increases. Instead, the critical policy error may prove to be the consequences of discretionary policy on the financial markets. The Fed has encouraged a decade of yield-seeking speculation, as investors try to avoid being among the holders of $6tn in zero-interest hot potatoes. By relentlessly depriving investors of risk-free return, the Fed has spawned an all-asset speculative bubble that may now leave investors with little but return-free risk.“ – bto: man kann es nicht besser auf den Punkt bringen.

- „It is true that low interest rates encourage elevated stock market valuations. But it is less appreciated that once valuations are elevated, low interest rates do nothing to mitigate the poor long-term market returns that typically follow.“ – bto: was noch ein gutes Szenario ist. Schlimmer sind einbrechende Vermögenspreise, die in Kombination mit hohen Schulden ein erhebliches Risiko darstellen.

- „In 1873, the economist and journalist Walter Bagehot wrote of savers’ aversion to low rates: “John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand interest rates of 2 per cent”. Forgetting this, in 2003, the Fed sent investors on a yield-seeking quest for alternatives to short-term interest rates of 1 per cent. Investors found that alternative in mortgage securities, with ultimately devastating consequences. The Fed has now encouraged an even broader and more extended speculative episode.“ – bto: das Ende der Immobilienblase war die Welt-Finanzkrise. Was folgt nun?

- „It can be prolonged only by making its consequences worse. The way forward is to embark on a well-announced return to systematic policy, never forgetting to ask whether the weak effects of monetary discretion on real economic outcomes are worth the risk of malinvestment and speculative distortion.“ – bto: dazu ist es viel zu spät. Es kann nicht so einfach aus der Politik ausgestiegen werden.

→ FT (Anmeldung erforderlich): „The Fed policy error that should worry investors“, 26. Januar 2022