Coronomics: Die Helikopter werden vorbereitet

Wohl nur die deutschen Politiker denken noch, die Schulden würden über harte Besteuerung der Reichen bereinigt. Die Wahrheit ist, die Helikopter kommen. Es lohnt sich, in die Geschichte zu blicken, um zu wissen, was auf uns zukommt. Das UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose hat dies vor einiger Zeit getan (und war auch schon mal Thema bei bto, aber dieser Wiederholung lohnt!):

Das vergessene Instrument

- “Policy debates have been focused upon the inflationary expectations that may be generated by monetary financing or related policies, consistent with New Consensus Macroeconomics theoretical frameworks. Historical examples of fiscal-monetary policy coordination have been largely neglected, along with alternative theoretical views, such as post-Keynesian perspectives that emphasise uncertainty and demand rather than rational expectations. This paper begins to address this omission.” – bto: Es wird also untersucht, wie die direkte Staatsfinanzierung in der Vergangenheit funktioniert hat.

- „In particular, we focus on the 1930s-1970s period when central banks and ministries of finance cooperated closely, with less independence accorded to monetary policy and greater weight attached to fiscal policy. We find a number of cases where fiscal-monetary coordination proved useful in stimulating economic growth, supporting industrial policy objectives and managing public debt without excessive inflation.“ – bto: was in der Tat wünschenswert wäre angesichts der Lage, in der wir uns befinden. Es geht doch nur darum, die Schuldenlast tragbarer zu machen.

- „The prohibition of monetary financing by central banks is a key element of the separation of fiscal and monetary policy that has become crucial to the New Macroeconomic Consensus (NMC), which views inflation-targeting via adjustments to interest rates as the most important activity of the central bank. This framework also prioritises monetary over fiscal policy, with fiscal policy limited to counter-cyclical short-run stabilisation effects.“ – bto: Klar ist aber, dass man mit tiefen Zinsen allein in eine Sackgasse fährt – in die der Überschuldung, aus der man so einfach nicht mehr herauskommt.

Seit der Krise sind die klassischen Instrumente stumpf

Nach 2009 funktioniert es aber nicht mehr: “Despite short-term interest rates being reduced to zero and quantitative easing (QE) programs pushing down the yield on medium and long rates, output growth has remained significantly below the pre-crisis period and central banks have repeatedly undershot their inflation targets. The apparent failure of the standard monetary policy transmission mechanism, whereby the lowering of interest rates should feed through to rising inflation and nominal demand in the real economy, has led to fundamental questions being asked of monetary policy. Meanwhile, public and private debt to GDP levels have remained highas austerity policies have failed to stimulate private sector investment and growth.” – bto: Es wäre gut, wenn wir endlich offen erkennen würden, dass es eben genau an den hohen Schulden liegt, dass es nicht mehr funktioniert.

- “The term ‘helicopter money’, popularised by Milton Friedman,has been widely used to describe monetary financing, with the preferred proposal being either a (one-off) tax break or cash handout to citizens or a permanent monetisation of a proportion of the fiscal deficit. The main advantage of such a policy, its advocates argue, is that it would boost demand without adding to either public or private debt levels (…).” – bto: Das hilft natürlich, wenn man den Nenner schneller wachsen lassen will als den Zähler.

- “Our review shows that for a large and economically successful period of the 20th century (1930- 1970), monetary financing in various guises was an integral aspect of macroeconomic policy. It was an important means by which governments were able to reflate economies following the Great Depression, finance World War II, and finance fiscal expansion, industrial policy and innovationin the post-war period despite high initial public debt-to-GDP ratios.” – bto: und das vor dem Hintergrund eines Booms, getrieben aus Basisinnovationen und Bevölkerungswachstum. Was zur Frage führt, ob es in einem gegenteiligen Umfeld auch so funktioniert. Ob es zudem wirklich der Treiber hinter Innovationen war, kann auch gründlich hinterfragt werden.

- “The historical evidence suggests different forms of monetary financing were not only used during economic downturns, but also more routinely to support fiscal expansion and Keynesian full-employment policies. (…) the current debate (…) neglects the possibility of longer term fiscal-monetary coordination to direct resources into the most productive areas of the economy – with resulting multiplier effects – and stimulate demand.” – bto: der Traum für alle Politiker! Sie können wieder die Welt retten, indem sie mehr Geld ausgeben.

Profiterwartungen entscheiden über das Wachstum

Sodann kommen wir erst mal zum Grundsätzlichen, zur Funktionsweise unseres Wirtschaftssystems, passend zu dem, was auf bto unter Eigentumsökonomik/Debitismus ausführlich diskutiert wurde. Immer mal wieder wert, nachgelesen zu werden. Ersparnisse folgen der Geldschöpfung durch Kredit: “(…) economists following Schumpeter and Keynes have emphasised that capitalist systems are ‘monetary production’ economiesin the sense that investment in the real economy requires financing prior to the existence of savings. Here the commercial banking sector plays a key role as it is able to issue liabilities upon itself to finance new investment for creditworthy borrowers without relying on pre-existing savings.” – bto: Wer das nicht versteht, der versteht auch nicht, wie die Wirtschaft funktioniert und erst recht nicht, wie es zu Krisen kommen muss.

- “For stable economic growth, advanced capitalist economies thus require investments that generate profits greater than debt commitments.” – bto: und vor allem Verschuldung zu produktiven Zwecken, nicht nur für Konsum und Spekulation!

Was dann zur Schlussfolgerung führt, dass der Staat und die Notenbank über die Beeinflussung der Gewinnerwartungen erheblichen Einfluss auf die Wirtschaft nehmen können, viel mehr als nur durch das Manipulieren der Zinsen. Dabei kann gerade eine Koordination der Geld- und Fiskalpolitik viel bewegen, vor allem, weil sich kein Zusammenhang zwischen dem Verlust der Unabhängigkeit der Notenbank und der Inflation feststellen lässt, so die Autoren in einem Überblick über die einschlägige Fachliteratur.

Zur Empirie des Helikoptergeldes

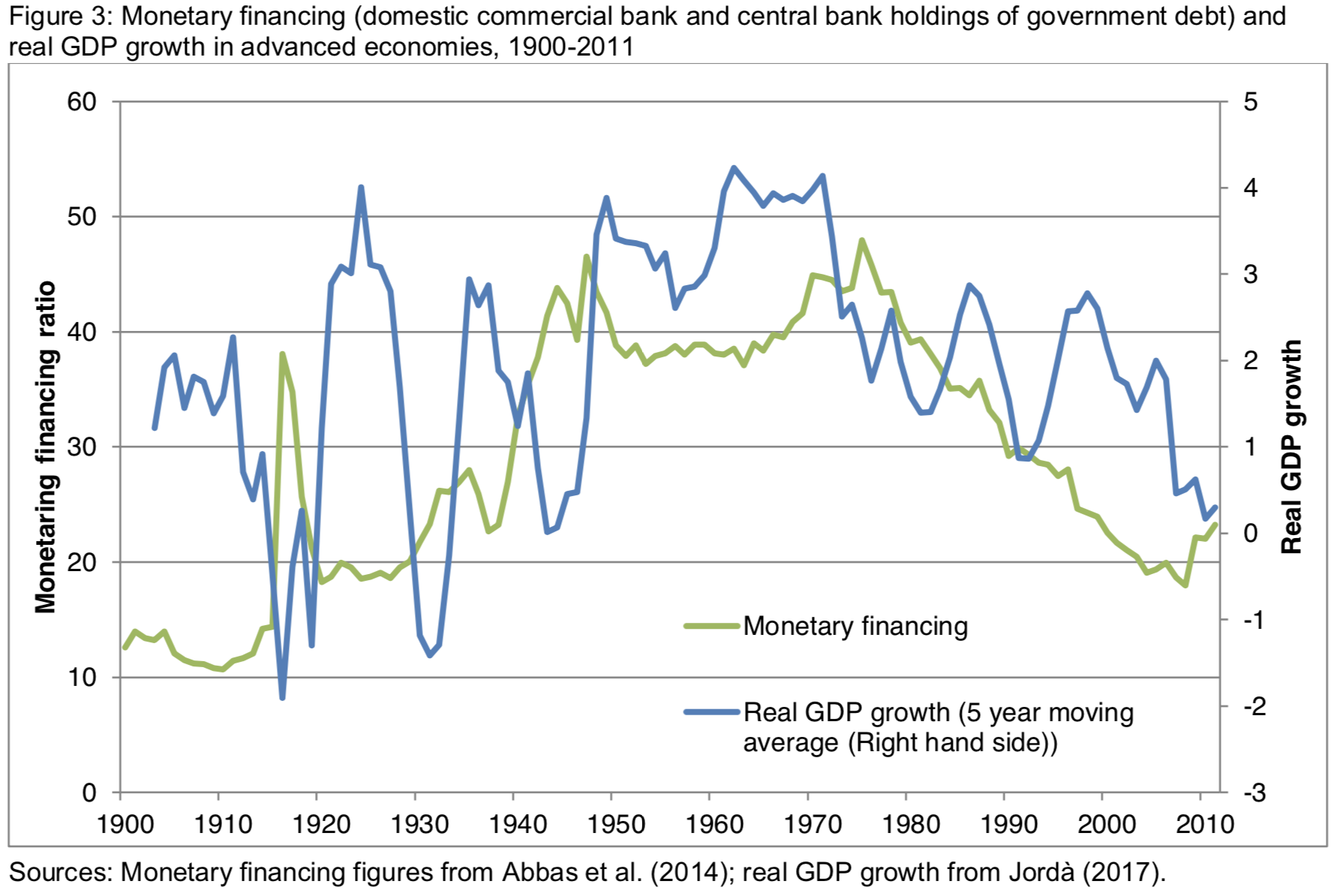

Zunächst zeigen die Autoren, welche Bedeutung die Notenbanken und die nationalen Geschäftsbanken bei der Staatsfinanzierung hatten:

- “(…) for long periods of the 20th century, in particular the 1930s-1970s period, there is clear evidence of fiscal-monetary policy coordinationwhereby both central banks and commercial banks were required (covertly or overtly) to purchase government debt to support fiscal policy objectives (including economic growth and debt sustainability). And even where the majority of monetary financing involved the purchasing of assets on secondary markets, this can still be seen as a form of indirect – or ‘two-step’ – monetary financing. This is because it will affect the demand for and yield on government debt, and reduce the net debt servicing burden of the government. It is also worth noting that up until the 1990s, over 50% of larger commercial banks were, in fact, state owned, making their lending policies more aligned with government economic policy generally.” – bto: Es ist klar, dass es hier eine sehr enge Beziehung gegeben hat und eigentlich auch wieder gibt.

Die Autoren sehen einen klaren Zusammenhang zwischen der Finanzierung von Staatsdefiziten durch Geschäftsbanken und Notenbanken, wobei auch hier natürlich gilt, dass eine Korrelation noch keine Kausalität ist:

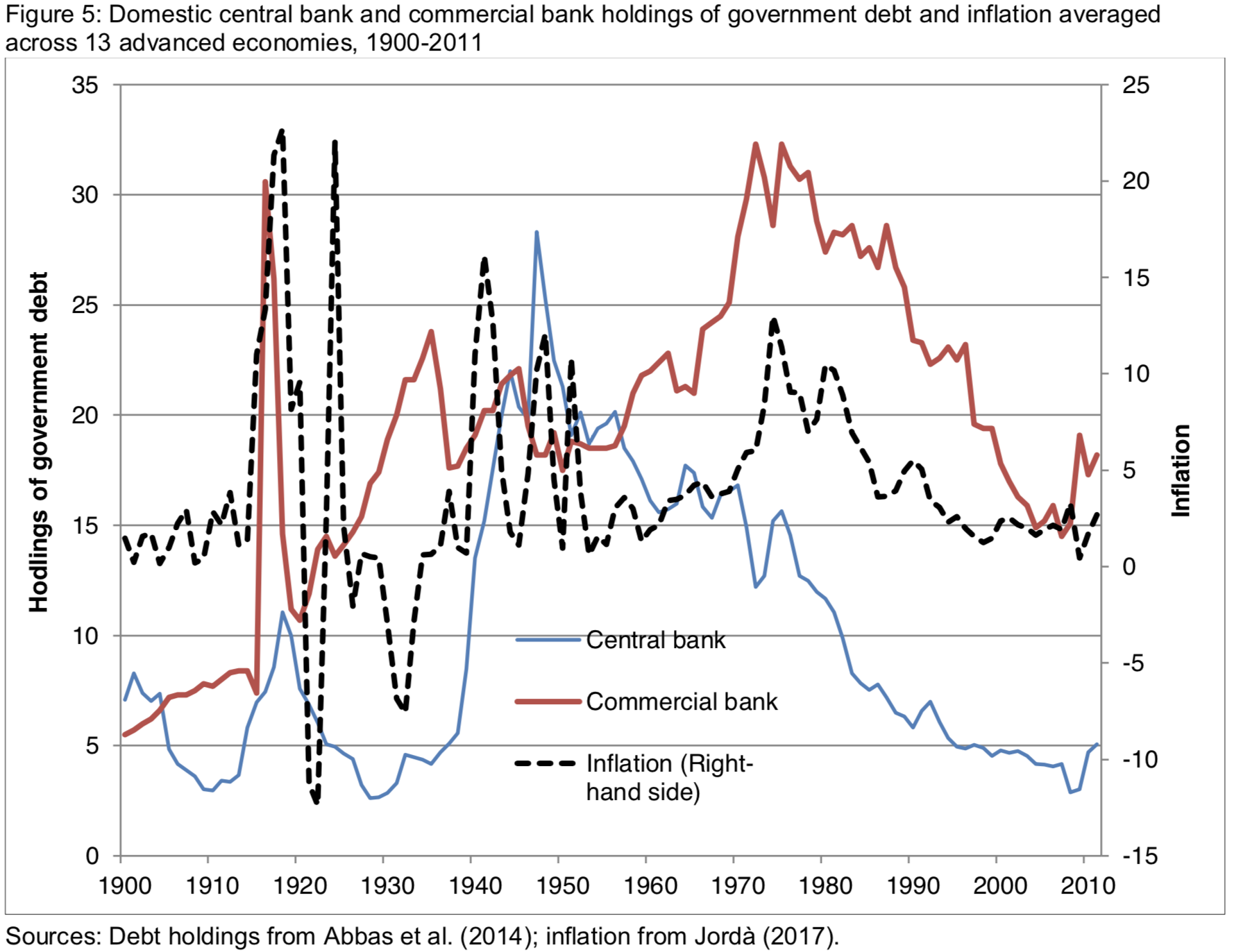

Es lässt sich auch kein klarer Zusammenhang mit der Inflation erkennen. (eventuell mit Blick auf die 1970er und die Notenbanken schon?)

Was bei den Autoren zum Fazit führt: „For most of the 20th century, large quantities of government debt were funded by monetary institutions, but there is little evidence that this led either to misallocation of capital and hence low growth or dangerously high levels of inflation.” – bto: Wir haben natürlich auch noch das Problem der Vermögenspreisinflation, die nicht in der Studie berücksichtigt wird. Ohnehin kann man fragen, ob die Konsumentenpreisinflation der richtige Maßstab ist.

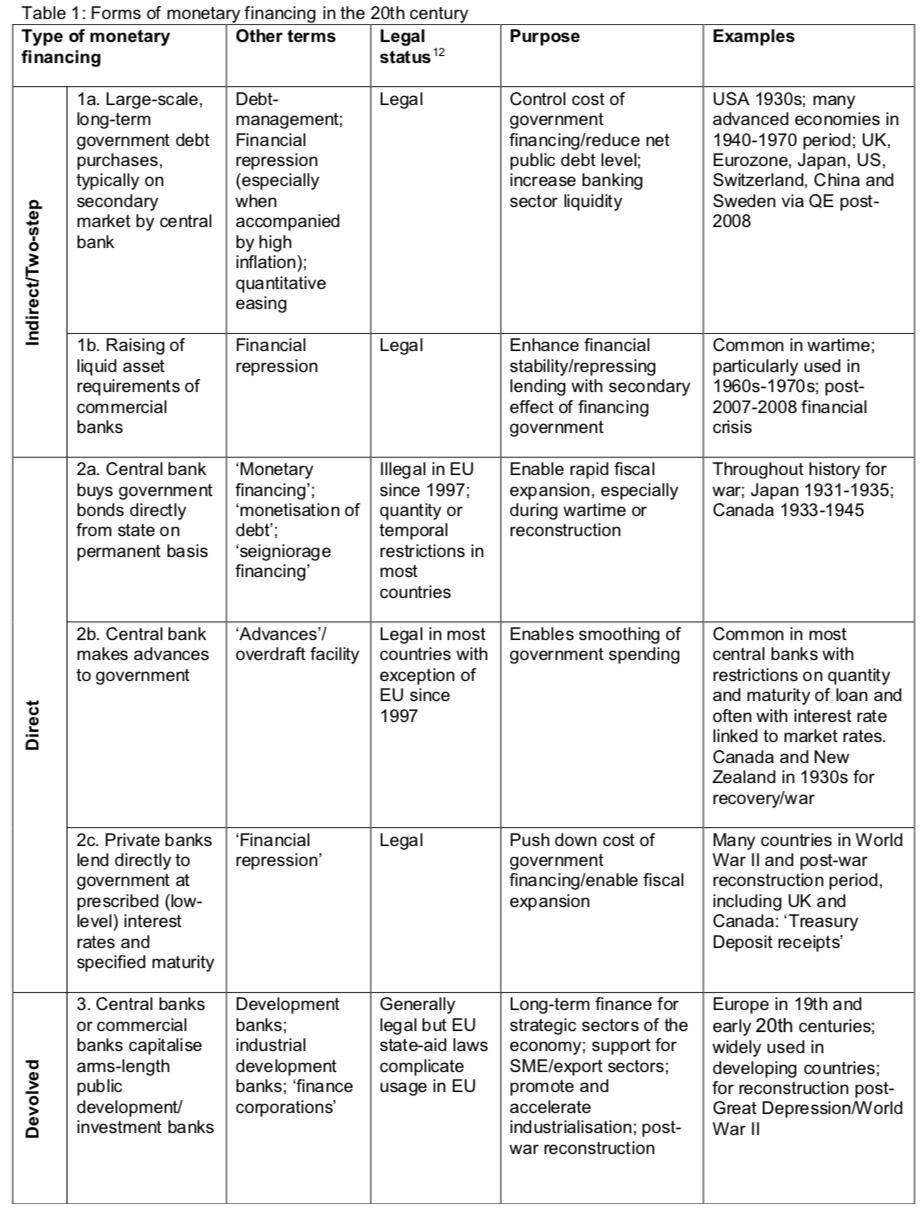

Diese Tabelle der Studie gibt einen guten Überblick über vergangene Phasen enger Kooperation zwischen Notenbanken und Staaten:

Beispiel 1: Direkte Finanzierung des New Deals

„When President Roosevelt came to power in 1933, he used the RFC to support his New Deal policies, creating public credit for infrastructure, machine-tool design machinery, manufacturing and agriculture, expanding the powers of the RFC to incorporate lending to industry (Freeman 2006). Between 1933-45, the RFC lent $33 billion (over $1.2 trillion in today’s dollars), making it the largest lending institution in the world at the time. (…) However, the establishment of the RFC coincided with another important piece of legislation: The Banking Act of 1932. A primary provision of the Act was to allow the Fed to use government securities as collateralfor Federal Reserve notes (on top of gold and commercial paper).” – bto: Die Finanzierung des Staates wurde also offiziell ermöglicht.

- “(…) the Federal Reserve began purchasing government securities from the open market. The programme was not only expansionary, but was unprecedented in terms of scale and scope, amounting to roughly 15% of the monetary base and 2% of GNP. (…) Indeed, minutes taken from Federal Reserve Board meeting in April 193316 indicate that under President Roosevelt the Federal Reserve Board voted to conduct open-market purchases in 1933 for the primary purpose of lowering the government’s debt servicing costs.” – bto: genau also das, was wir auch in der nächsten Phase der Krise sehen werden.

Beispiel 2: Schuldenmonetarisierung in Japan (1931-1937)

Ja, das gab es dort schon früher. So gesehen darf es nicht wundern, wenn die Japaner in die gleiche Richtung wieder unterwegs sind.

- „One of the most successful examples of direct debt monetisationwas the Takahasi government in Japan in the 1930s. Following the abandonment of the Gold Standard in 1931 and the resulting devaluation of the yen, the Takahasi administration embarked on a massive fiscal expansion that reflated the economy out of the Great Depression. The expansion was largely funded via central bank money creation. In November 1932 the government began to sell entire issues of its deficit bonds directly to the Bank of Japan rather than private institutions. Inflation and excess liquidity were then controlled by the Bank of Japan selling government bonds onto the open market. Central government spending rose from ¥1.42 billion (10.7% of GNP) in 1931 to ¥2.25 billion (14.7% of GNP)in 1933, a level at which it remained fixed, expanding the deficit from a 0.1% of GDP surplus to a 6.1% deficit.” – bto: wie sich die Zeiten doch ähneln. Dass es diesmal nicht so gut klappt, sollte eine Warnung für uns sein. Heute haben wir nämlich den demografischen Gegenwind, was es eben ein echtes Ponzi-Problem macht.

- Damals hat es gewirkt: „By 1933 Japan had emerged from the Great Depression and there was no significant inflation; by 1934 it was moving out of trade deficit into surplus. Inflation began to build up in 1935 and Takahashi reduced government spending, especially military spending, to rein it in and sterilised his previous budget deficits by selling bonds back into the open market.“ – bto: Erst danach kam es zu einer Übertreibung, nachdem Takahasi ermordet wurde und der Nachfolger das Militär großzügig mit frischem Geld finanzierte.

Beispiel 3: Zwangsfinanzierung durch Privatbanken

- So geht es natürlich auch: Man schreibt den Banken einfach vor, einen bestimmten Anteil in Staatsanleihen zu halten (oder ermuntert wie heute in der Regulierung): „A third version of monetary financing is for governments to borrow directly from private banksin much the same way that households and businesses do today.Given that sovereign states with their own currencies and central banks do not, in practice, default (as central banks can create currency ex nihilo), governments should be in a position to issue long-term loan contracts at very low rates of interest; alternatively, states could simply force private banks to accept the loan issued at a maturity and rate of the government’s choosing. During and post-World War II a number of governments engaged in this practice, including the US, (…) Canada); and the UK. In the UK, the Treasury, following Keynes’ advice, forced banks to buy Treasury Deposit Receipts (TDRs) at 1.125% interest to help finance World War II.” – bto: Und auch nach dem Krieg gab es noch lange Vorschriften, die eine Anlage zu negativem Realzins, financial repression, durchsetzte, um die Schulden zu entwerten.

Fazit

- „A number of economists have argued that central banks’ QE policies would be effective at stimulating demand if they committed to permanently monetising a proportion of their asset purchases: the so-called helicopter drop. (…) Since central banks with sovereign currencies cannot default, the choice of whether to monetise becomes essentially a political-economy question.” – bto: Und deshalb wette ich darauf, dass diese zu gegebener Zeit mit “Ja” beantwortet wird.

- “Our examination of historical trends and case studies suggest that monetary financing was an effective tool in supporting standard macroeconomics policy goals such as nominal GDP growth and industrial policy without excessive inflation. (…) None of this is to deny that under certain other conditions it is possible that monetary financing will lead to inflation. However, our evidence suggests the reasons for this may not be those suggested by the rational expectations models featured in New Consensus economic theory which have an overly deterministic view of the relationship between monetary financing and inflation and rest on a faulty understanding of the role of commercial bank credit creation. Weak governance and tax-raising powers, corruption and war, loss of control over exchange rates or bottlenecks where the economy is at full capacity may be stronger candidates to explain extended periods of inflation or hyperinflation.” – bto: Das Umfeld hoher Schulden und die Demografie gepaart mit der Globalisierung der (Arbeits-)Märkte und der Automatisierung können auch künftig die Inflation in Zaum halten, egal was die Notenbanken machen. Allerdings dürfte sich die Vermögenswertinflation beschleunigen.

- “(…) in most advanced economies today there are legal and constitutional impediments to governments considering borrowing directlyfrom central banks for extended periods. The rationale for this should perhaps be scrutinised as part of the wider re-examination of monetary and macroeconomic policythat now appears to be under way in the post-crisis period, when central banks have been unable to stimulate aggregate demand or inflation using adjustments to interest rates.” – bto: was – wie gesagt – gerade auch in Europa passieren wird.

- “In the shorter term, however, governments could consider debt monetisation via borrowing directly from private banks at below market interest rates, for which there are no legal or constitutional barriers. Monetary financing may provide greater fiscal autonomy to governments, not least in the Eurozone, whose debt may be subject to speculative attacks and/or who find it increasingly challenging to increase deficits or raise taxes from a political economy perspective.” – bto: Bingo!