“Clearing up some misconceptions about how the stock market works”

Vor einigen Wochen habe ich an dieser Stelle einen Beitrag diskutiert, der aus verschiedenen Blickwinkeln die These eines überbewerteten US-Aktienmarktes widerlegen wollte. Ein entscheidender Punkt war dabei das Verhalten der Unternehmen, die nach Ansicht des Autors immer Nettosparer und deshalb Käufer von Aktien sind, während private Haushalte tendenziell immer entsparen. Ich fand das als eine problematische Sicht, weil es per Definition nicht ewig so sein kann, dass die unproduktiven Schulden immer weiter anwachsen.

→ Alles super mit dem Bullenmarkt

Vermutlich haben dies auch die Autoren von FT Alphaville gelesen und sich deshalb vertieft mit der Bewertung von Aktien und der Struktur der Käufergruppen beschäftigt: “You can learn lots of interesting things by closely studying America’s Financial Accounts (formerly known as the Flow of Funds) published by the Federal Reserve, such as how the US stock market actually works.” – bto: eine interessante Frage!

- “First, the standard theory: Just like everyone else, companies that want to spend more than they take in can raise money by selling financial assets to investors. (…) Shareholders have a chance for much higher returns than bondholders, but also much greater odds of losing all their money.” – bto: Das ist als solches auch heute noch richtig.

- “You’d probably also expect that companies in the aggregate raise more money by selling stocks to investors than they spend buying them back, while households buy more shares than they sell.” – bto: In der Tat würde ich das unter normalen Umständen erwarten.

- “Yet data from the Financial Accounts make it quite clear that US nonfinancial corporations buy more stock than they sell, and have done so for decades. (…) Since 1960, cumulative net equity issuance has been negative $6.3 trillion.” – bto: Das ist beeindruckend und würde meines Erachtens eine Tendenz zu immer höherem Leverage im System beschreiben.

- “The flip side of this is that American households and nonprofits, rather than net investors in the stock market, are actually net sellers. (…) Household equity holdings have grown over time because the prices of the shares they don’t sell have risen more than enough to compensate.” – bto: Das finde ich, wie bereits gesagt, eine ungesunde Entwicklung. Eine Volkswirtschaft prosperiert durch Investitionen, nicht durch anhaltende Zusatzverschuldung der privaten Haushalte.

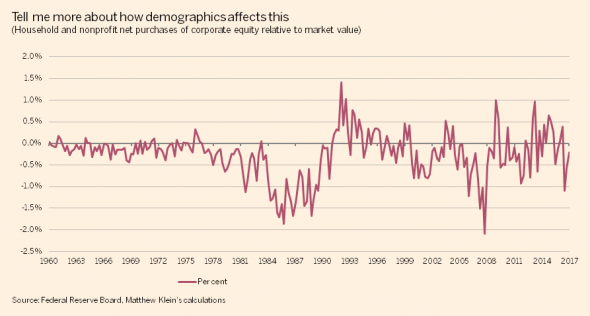

- “(…) stock prices go up and down (generally up) over time, while the dollar tends to lose value relative to goods and services. The charts below correct for this by dividing quarterly net flow against the total amount of nonfinancial corporate equity outstanding at each point in time.(Market value).” – bto: Was man sehr schön sieht, ist, dass in dieser Darstellung der große Buyback-Boom in den 1980er-Jahren war. Damals war der Markt übrigens wirklich noch billig.

Quelle: FINANCIAL TIMES

- “The big change was in the 1980s. Falling real interest rates (from extraordinarily high levels) and exploding earnings multiples (from an extremely low base) encouraged companies to shift their financing mix from equity to debt. At the same, deregulation, particularly relating to the government’s approach to antitrust, encouraged a wave of mergers and acquisitions, often funded by debt. The invention of the leveraged buyout was another big contributor to de-equitisation.” – bto: Man könnte auch sagen, es war der Beginn der großen Schuldenorgie!

- „The behaviour of households and nonprofits also looks less outlandish when scaled against market values. With a few notable exceptions, they have tended to sell shares as prices rise, minimising the overall shrinkage in their position:” – bto: was dennoch interessant ist, weil allgemein befürchtet wird, dass die große Verkaufswelle der Babyboomer erst noch bevorsteht.

Quelle: FINANCIAL TIMES

- “(…) the new supply of equity has been pretty stable over the past two decades. Contrary to fears about the death of public markets, companies are still happy to sell shares to raise money:” – bto: wobei man immer genau hinschauen sollte, ob es sich lohnt, da mitzumachen. Siehe Snap.

Quelle: FINANCIAL TIMES

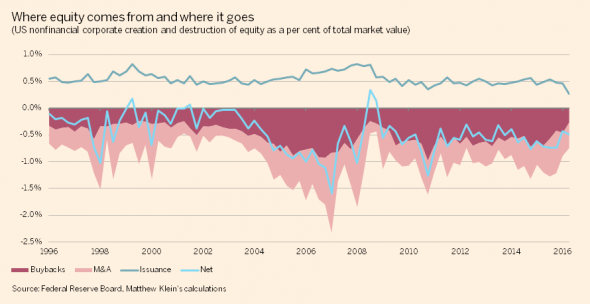

- “This last chart puts everything together by scaling buybacks, mergers and acquisitions, new issuance, and the net creation of nonfinancial corporate equity against market value:”

Quelle: FINANCIAL TIMES

- “You can see that M&A is the most volatile component, while the pace of corporate stock buybacks tends to be pretty stable relative to the level of share prices. Contrary to popular belief, there hasn’t been a systematic increase in the rate of share buybacks. There was a temporary increase during the excesses of the 2005-07 period but that’s about it.” – bto: Und dennoch haben wir eine Welt, in der es als normal angesehen wird, dass die privaten Haushalte Nettoverkäufer sind. Vielleicht bin ich da jedoch überkritisch. Wenn die Marktwerte stärker steigen, könnte man auch sagen, dass sich die Vermögensposition nicht ändert, sondern der geringeren Stückzahl höhere Stückpreise gegenüberstehen. Dann ist es aber auch eine Täuschung, wenn man auf die Aktienindizes blickt.

→ FT Alphaville: „Clearing up some misconceptions about how the stock market works“, 28. Juli 2017