“Can further monetary stimulus still be effective?”

Anders steht es mit der Frage, ob die Politik die Banken so schwächt, dass diese keine Kredite mehr geben können, und somit das Gegenteil von dem bewirkt, was eigentlich beabsichtigt ist? Vor allem die geringeren Margen der Banken sollen dafür die Ursache sein. Doch, stimmt das? Martin Sandbu von der FT bringt überzeugende Gegenargumente:

- “The European Central Bank took a sharp expansionary turn this month (…) They were right to do so, given the evidence that the eurozone economy is underperforming and further threats to growth on the horizon.” – bto: Ja, die Wirtschaft läuft nicht gut. Aber daran ändert auch das billige Geld der EZB nichts. Es ist ein fundamentales Problem, wie wir wissen.

- “(…) the debate will shift from the need for policy action to the effectiveness of any further monetary loosening. Specifically, can further interest rate cuts stimulate aggregate demand when rates are already below zero? Oder führt die ‘reversal rate’ dazu, dass die Banken weniger ausleihen? (…) It is defined as the (likely to be negative) interest rate below which rate cuts lead to less lending by banks. In other words, the reversal rate is the level of interest rates where the most traditional type of central bank ‘stimulus’ is actually contractionary.” – bto: Das ist die These, wonach negative Zinsen genau das Gegenteil bewirken, als sie eigentlich erreichen sollen.

- “When the central bank moves rates, this can affect the capital position of banks by changing today’s value of future profits. More specifically, a rate cut worsens their capital position if it squeezes their net interest income (their profit on lending) enough to outweigh a capital gain on securities they own. A worsened capital position, in turn, creates incentives to shrink lending or deleverage balance sheets for banks that find themselves close to the equity thresholds they are legally required to respect.” – bto: klar. Wenn man mit der Vergabe von Krediten den Verlust erhöht, macht es niemand. Doch ist das schon der Fall? Sandbu zeigt, noch nicht.

- “For there to be a reversal rate, all of the following must be true. Lower rates must lead to narrower net interest margins for banks. At the same time, those lower margins must not be offset by bigger lending volumes — which would keep interest income (rather than margins) stable. And banks must actually find themselves at risk of breaking their capital thresholds.” – bto: Und auch hier wissen wir, dass es nicht so gut um die Kapitalkraft geht.

- “What is the reality? First, while there is a broad sense that lower rates tend to go with tighter interest margins for banks, the squeeze on that margin is not quantitatively large. An earlier Bundesbank study, for example, found that a 1 percentage point fall in interest rates reduced the net interest margin for German banks by 0.07 percentage points.” – bto: Das ist ärgerlich, aber nun wirklich kein so großes Problem.

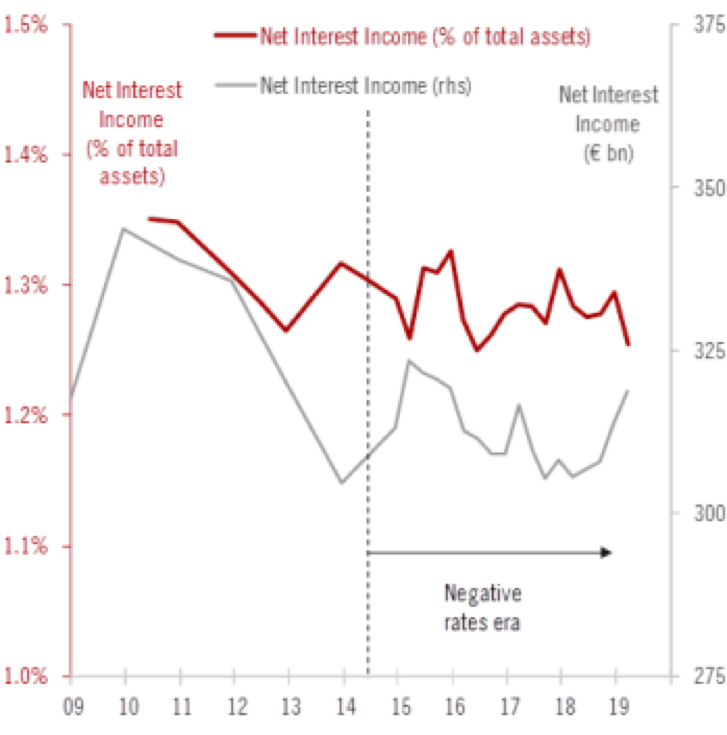

- “(…) there is no evidence that the ECB’s ultra-low interest rates have done any damage at all to eurozone banks’ net interest income. As Frederik Ducrozet and Nadia Gharbi, analysts at Pictet, have highlighted, that income has been stable since well before the ECB went negative, both in absolute terms and as a percentage return on assets.” – bto: Das ist eine wirklich interessante Feststellung. Es kam nicht zu der Reduktion der Margen für die Banken.

Quelle: FINANCIAL TIMES

- “(…) French and German banks have seen stable net interest incomes. Italian ones have recovered after a dip; Spanish banks have seen their net interest incomes rise in the negative rates era.” – bto: wobei es nicht verwundert, dass die Deutschen so schlecht dastehen. Liegt an der Fragmentierung des Marktes. Bei Frankreich stutzt man mehr.

- “(…) Given that banks fund themselves with shorter maturities than they lend, the shape of the yield curve matters, and the central bank can choose to target shorter and longer interest rates differently. If bank profitability were a big problem, nothing stops the ECB from cutting short rates more aggressively than long rates, thereby boosting the reward for banks’ core function of maturity transformation. (…) The ECB is nowhere near to running out of ammunition.”- bto: Das ändert nichts daran, dass die Munition nicht wirkt.