Blase an den Anleihemärkten?

Angesichts des Rekordvolumens an Anleihen, die weltweit mit negativen Zinsen gehandelt werden, liegt die Frage nahe: Sind wir hier in einer Blase, vielleicht sogar der ultimativen Blase unserer immer mehr außer Rand und Band geratenen monetären Ordnung? John Authers nimmt sich des Themas an und kommt zu der klaren Aussage, ja, es ist eine Blase. Doch wie immer ist es schwer vorherzusagen, wann sie platzt.

- „Longview Economics Chief Market Strategist Chris Watling published a fascinating research note last week applying the framework introduced by Charles Kindleberger in his book “Manias, Panics, and Crashes.” (bto: übrigens ein wirklich lesenswertes Buch!) (…) Kindleberger needed to satisfy four conditions before he diagnosed a bubble.” – bto: Und die schauen wir uns jetzt an.

- „(…) cheap money underpins and creates the bubble.” – bto: Das ist klar, denn nur mit der Schaffung von umfangreicher Liquidität gibt es genug Treibstoff für diese Entwicklung. Authers sieht diese Bedingung als erfüllt an. Ich auch!

- “(…) debt is taken on during the bubble build-up, which helps fuel much of the speculative price increases (e.g. buying on margin).” – bto: Und das wirkt in beide Richtungen, wie ich in meinem Beitrag Margin Call in der Weltwirtschaft erklärt habe. Authers fragt die offensichtliche Frage: “Are people really buying negative-yielding bonds on margin?”, die ich mir auch gestellt habe. Kaufen Spekulanten auf Kredit ein Wertpapier mit garantiertem Verlust? Doch nur, wenn sie mit einer Kurssteigerung rechnen. Offensichtlich ja, denn „ According to Watling, risk parity funds use debt to buy bonds on margin, while CTA momentum investors will also be buying on margin (i.e. with implicit debt). More interestingly, though, the biggest buyers of sovereign debt in the past decade have been the major central banks. Their purchases have been made with newly created money.” – bto: was wir schon lange wissen und was uns zusätzlich besorgen muss. Denn die Notenbanken sind perfekte Kontra-Indikatoren. Ich erinnere an die Verkäufe von Gold am Tiefpunkt.

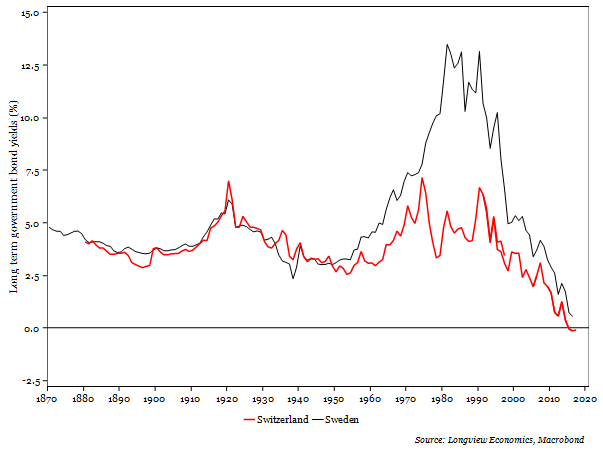

- “once a bubble is formed, the asset price has a notably expensive valuation.” – bto: wobei dies immer bestritten wird in der Blase. Man findet gute Argumente dafür, dass es nicht so ist, sondern ganz anders. So ist es ja auch heute, wie Authers sogleich erläutert. “(...) it is evident that bonds are very expensive. (…) Watling offers a couple of very long-term comparisons. These are government bond yields from Switzerland and Sweden dating back to 1870:”

Quelle: Bloomberg

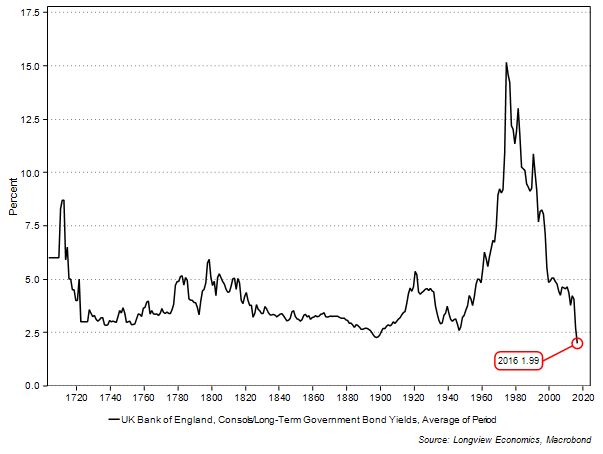

- “(…) here is the rate on U.K. ‘consols,’ or perpetual bonds that can be redeemed whenever the government wants, back to 1700:” – bto: Und das ist wirklich ein cooles Chart!

Quelle: Bloomberg

- “(…) Watling argues perfectly convincingly that the concept of negative yields is inconsistent with how a financial system should work: ‘in a normal system, savers are compensated for deferring consumption and thereby paid for the time value of their money and borrowers pay for the privilege of borrowing money. (…) if borrowers don’t pay for the privilege of borrowing money, capital allocation discipline should then break down, as the rate of return hurdle for new projects falls (or even potentially turns negative), making more and more projects feasible and overly boosting supply/competitive pressure.’” – bto: Genauso ist es doch offensichtlich. Die Zombifizierung ist die offensichtlichste Folge dieser Entwicklung. Und sie führt wiederum zu geringerem Wachstum, noch mehr Druck auf die Schuldner und damit zum Zwang noch tieferer Zinsen. Authers: “All of us can see, more or less, that these valuations are in the exceptional territory that merits the word ‘bubble.’” – bto: So ist es.

- “(…) there’s always a convincing narrative to ‘explain away’ the high price. Reflecting that, there’s a wide acceptance in certain quarters that the price is rational (and ‘this time it’s different’).” – bto: Gerade Letzteres ist immer wieder zu beobachten, was erstaunlich ist. Denn eigentlich müsste gerade die heutige Generation wissen, wie gefährlich das ist. Authers dazu: “the current narrative (…) is that western economies are stuck in a morass, and central banks will have no choice but to keep cutting rates and printing money. In the Japanification of the world, bond yields will continue to fall. (…) Kindleberger’s condition of a convincing and pervasive narrative is satisfied. (…) bonds are in a bubble. QED.” – bto: Aber was nun? Denn an den Bonds hängen alle anderen Märkte, wie wir wissen. Sie treiben die Preise für andere Vermögenswerte nach oben, weil der Abzinsungssatz in die Berechnung entsprechend einfließt.

- “Kindleberger found that it was almost always one factor that burst a bubble: the removal of cheap money. Given the behavior of central banks in recent weeks, it looks as though cheap money is going to keep flowing for a while. Ergo, this bubble can expand further before it bursts. We are in the zone of what a decade ago was referred to as a ‘rational bubble’ – asset valuations were extreme, but with central banks resorting to extreme measures, the rational response was nevertheless to buy.” – bto: Authers sieht nur ein Risiko, sollte es doch zu einem Handelsabkommen zwischen China und den USA kommen und/oder die Weltwirtschaft wieder mehr wachsen. Ich sehe noch ein weiteres Risiko: Vertrauensverlust in die Qualität der Schuldner. Kommt es trotz des billigen Geldes der Notenbanken zu einer Welle an Zahlungsausfällen – oder beispielsweise eine große Bank muss unter Beteiligung der Kunden „gerettet“ werden – kann es zu steigenden Risikoprämien und damit Zinsen kommen. Unwahrscheinlich? Vielleicht.

Quelle ist der sehr lesenswerte und kostenfreie Bloomberg-Newsletter von John Authers.