Bank für Internationalen Zahlungsausgleich sieht wachsende Inflationsrisiken

Einmalige Krise

- “Economic activity has collapsed even more steeply than in the Great Depression, to even greater depths than those of the GFC. Many economies shrank by an annualised 25–40% in a single quarter, and some saw unemployment rates soar into the teens within a couple of months. Moreover, and unlike the GFC, the crisis has been truly global, sparing no country in the world.” – bto: Und es ist der Auftakt für Coronomics.

Anfälliges Finanzsystem

Ich erinnere mich, wie ich zu Anfang der Corona-Krise darüber diskutierte, ob es denn auch eine Finanzkrise sei:

→ STELTERS MAILBOX: Haben wir eine Finanzkrise, ja oder nein?

Die Antwort der BIZ ist eindeutig: Nur mit Not wurde eine verhindert:

- “Regardless of financial conditions, the shock would have been enormous. But, while not at the origin of the shock, the financial sector has played an important dual role. It has acted as a key transmission channel for the shock back onto the real economy, although central banks have been quick to neutralise this impact (see below). And, less appreciated, it has also helped shape initial conditions, heightening the economy’s sensitivity to the shock.” – bto: Das System war nicht krisenfest, sondern hoch anfällig.

- “Given their forward-looking nature, global financial markets reacted faster than the real economy. True, when problems appeared to be confined to East Asia, markets hardly moved: in fact, by end-January, equity prices had reached a historical peak. But when news about the surprisingly rapid spread of the virus in Europe hit the wires in late February, equity markets buckled, volatilities spiked and bond yields bottomed. While, at the outset, markets functioned rather well, they continued to dance to the tune of the virus and became increasingly disorderly. Spreads soared on corporate and EME debt securities, which had largely been spared in the first phase. In March, a flight to safety turned into a scramble for cash, in which even gold and US Treasury securities were dumped to meet margin calls. It was precisely at this point that markets threatened to freeze entirely. While the US dollar markets, both on- and offshore, stood at the epicentre, other markets too were roiled to varying degrees.” – bto: Es ist halt immer wieder das Problem: Schulden wirken als Brandbeschleuniger.

- “Equally important has been the role of financial factors in shaping initial conditions. After slowly building up, partly on the back of unusually low and persistent interest rates post-GFC, financial vulnerabilities have exacerbated the impact of the shock on economic activity – and may continue to do so as the crisis unfolds. These vulnerabilities can be summed up as overstretched financial markets and high non-bank leverage.” – bto: Und die Politik der letzten zehn Jahre hat genau das verstärkt!

- “First, aggressive risk-taking prevailed in financial markets before the pandemic. Valuations were frothy. Credit risk showed clear signs of underpricing in both advanced and emerging market economies. (…) as is typical in such cases, market liquidity was fragile. This was reflected in the popularity of illiquid investments financed through short-term funding, investment funds and other such vehicles; or in widespread relative value “arbitrage” trades by hedge funds that ended up causing turmoil in the US Treasuries market.” – bto: Strategien, die man nur verfolgt, wenn man davon ausgehen kann, dass man (immer wieder) von den Notenbanken gerettet wird.

- “Second, and closely related, non-bank leverage was high. Corporate debt was elevated in many advanced and emerging market economies. Examples are leveraged loans, collateralised loan obligations and, much underappreciated, private credit – a form of financing for smaller and typically riskier firms that is a locus for highly illiquid investments, almost as large as the leveraged loan market and just as overstretched. Corporate debt levels burgeoned while credit quality deteriorated, as reflected in the rising share of debt rated BBB, just one notch above non-investment grade (“junk”). Household debt was high in several countries less affected by the GFC, (…) sovereign debt loomed large in several advanced economies and, above all, in EMEs, partly as a result of the policy response to the GFC.” – bto: Natürlich war das die Folge der Geldpolitik. Es ist schon merkwürdig, dass das andere Volkswirte anhaltend leugnen!

- “A silver lining in this sobering picture is the state of the banking system. In contrast to the GFC, the pandemic found banks much better capitalised and more liquid, thanks largely to the post-crisis financial reforms coupled with a more subdued expansion. (…) Nevertheless, banks face challenges. This real-life stress test is more severe than the scenarios supervisors adopted in their pre-crisis solvency exercises. One challenge is chronically weak profitability in a number of banking systems, most notably in the euro area and Japan.” – bto: Und warum sind die Banken so schwach auf der Brust? Genau, weil die tiefen Zinsen ihnen die Ertragskraft rauben.

Richtige Reaktion

Sodann lobt die BIZ die Reaktion der Politik auf Corona:

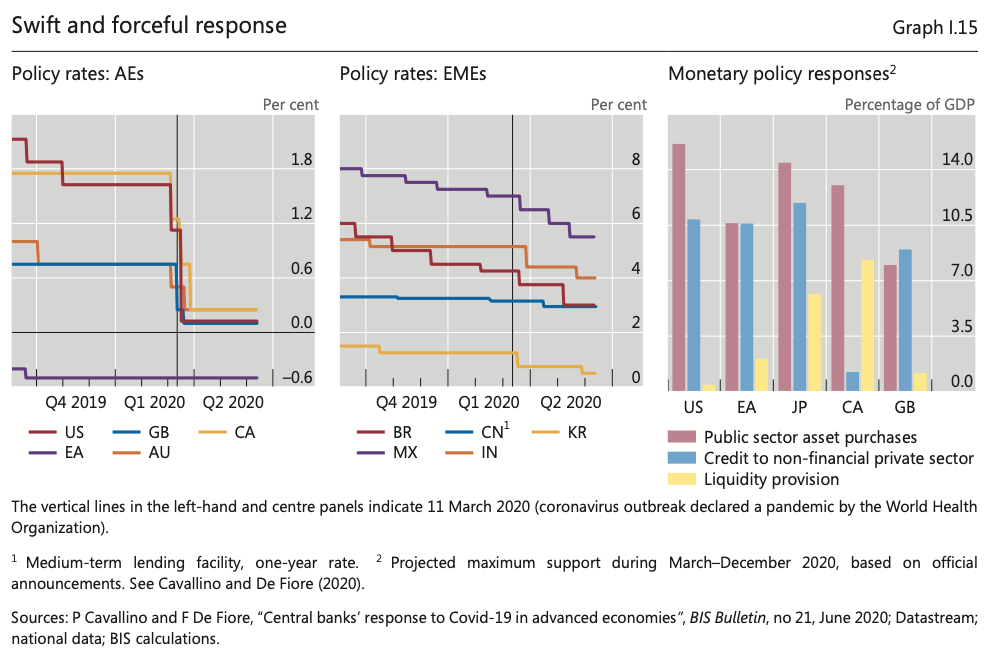

- “Central banks once again reacted swiftly and forcefully to stabilise the financial system and support credit flows to firms and households. The initial interest rate cuts, while called for, were limited in their soothing effect. The impact was much larger once central banks started to act in their time-honoured role of lenders of last resort, supplying badly needed liquidity and addressing dysfunctional markets. By stabilising the financial system and restoring confidence, these measures also prevented the transmission of monetary impulses to the economy from breaking down.” – bto: Ja, da waren sie wieder, die Helden der Notenbanken!

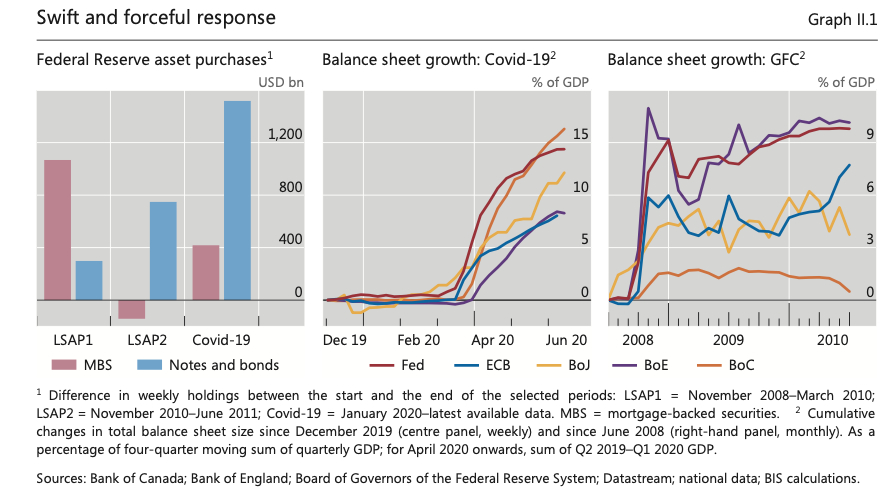

- “The nature of the shock required central banks to push harder than in the past. While some central banks could simply extend previously applied measures, others broke new ground. In addition to purchasing government debt on a massive scale, many central banks also bought private sector securities or relaxed their criteria for collateral, venturing further down the creditworthiness scale than ever before. (…) In the process, some central banks crossed former ‘red lines’, resorting to measures that would once have been seen as off-limits.” – bto: Vermutlich denkt nur die BIZ, dass diese roten Linien nicht ohnehin mal überschritten werden …

Quelle: BIZ

- “The rapid growth of market finance since the GFC meant that central banks once again broadened their historical role of lenders of last resort to that of buyers or dealers of last resort.” – bto: Käufer der letzten Instanz. Wow.

Quelle: BIZ

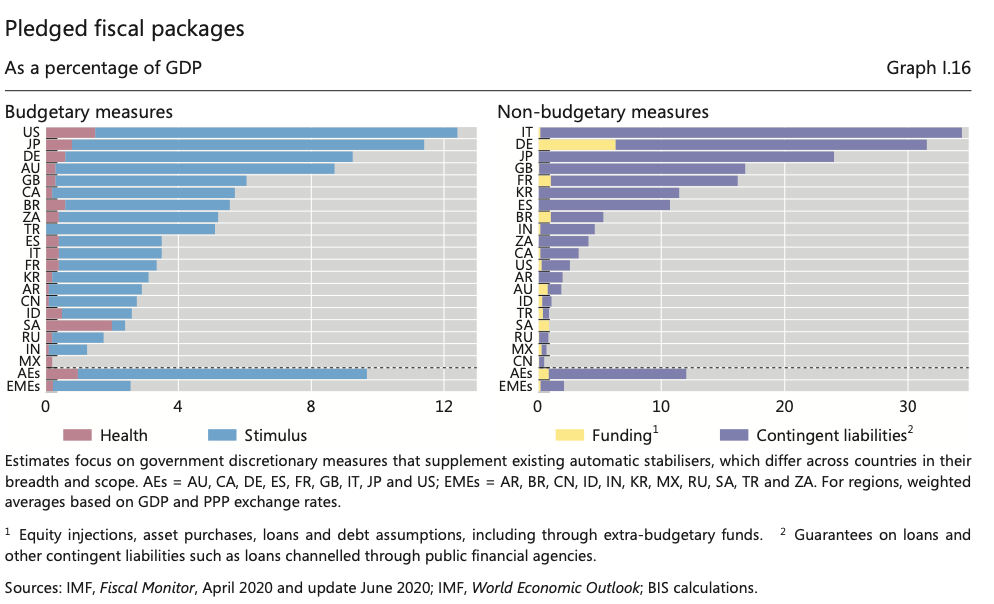

- “The bulk of the response has rightly consisted of fiscal measures. Some, especially at the outset, were aimed at shoring up liquidity by, for example, postponing taxes or allowing debt moratoriums. But the vast majority transferred real resources to households and firms, either outright or conditionally.” – bto: Und darin liegt der große Unterschied zur Finanzkrise!!

- “Conditional transfers have taken the form mainly of credit guarantees, which are activated only in the event of default. Their key role has been to back up risk-taking so as to keep credit flowing. In some cases, the beneficiaries have been banks: it is one thing to have the resources to lend, quite another to deploy them without a clear incentive to do so when prospects are deteriorating and uncertainty looms large. In other cases, the recipient has been the central bank itself. Governments have provided full or partial indemnities to insulate central banks from losses, sometimes by taking equity stakes in special purpose vehicles funded by central banks. In a similar vein, some beneficiaries have been the creditors of non-financial firms, such as in rescue operations for airlines or other large businesses.” – bto: Das bedeutet nichts anderes als die faktische Verstaatlichung der Wirtschaft, man könnte auch sagen, die finale Zombifizierung!

Quelle: BIZ

- “In the current crisis, which started in the non-financial sector, the authorities may need to fund households and firms directly, especially if the financial sector is overburdened. If and when insolvencies emerge, policy has two aims. First, to restructure balance sheets – the size as well as the debt and equity mix – so as to deal with a debt overhang. Second, to promote the underlying real adjustment, by reducing excess capacity and helping shift resources from less viable sectors and firms to the more promising ones. If these measures succeed, they can pave the way for a healthy recovery.” – bto: Diese Maßnahmen sind der Albtraum jedes Politikers und deshalb werden wir genau das Gegenteil erleben!

Wie kommen wir da wieder raus?

Der Ausblick:

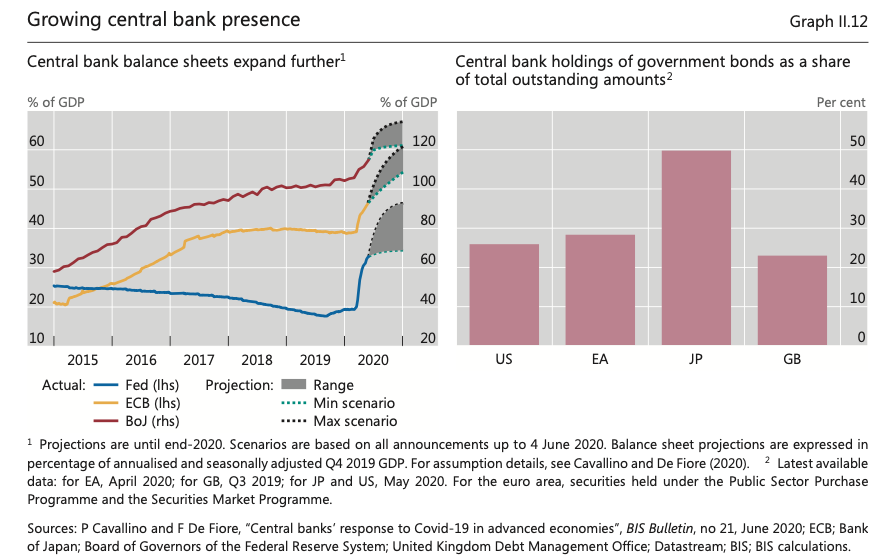

- “As the future unfolds, monetary policy will face serious challenges. This is so whether it is disinflationary or inflationary pressures that come to the fore. In either case, exit difficulties combined with limited policy space are likely to play a role. While the future course of inflation is uncertain, disinflationary pressures are likely to prevail for some time. To be sure, the pandemic shock has tended to reduce productivity. Unable to accommodate the usual number of customers because of social distancing rules, airlines, restaurants and hotels will face cost pressures. Global value chains are likely to sustain long-lasting damage, which may be partly irreversible. Even so, precautionary saving and the limited pricing power of firms and labour will probably persist, limiting any second-round effects. Indeed, the experience with previous pandemics is consistent with this picture. This scenario would rather closely resemble the pre-pandemic shape of things. It is a world in which central banks test the limits of their expansionary policies and struggle to push inflation up.” – bto: Das ist die Frage. Ist es in diesem neuen Umfeld letztlich nicht leichter, die Inflation nach oben zu treiben?

- “But as we peer further into the future, a quite different picture could emerge. In this case, we would be speaking not of inflation evolving within the current policy regime, but of a more fundamental change. Here the economic landscape would, in some respects, look like the one that materialised immediately after the Second World War. This scenario could come into being if a lengthy pandemic were to leave a much larger imprint on the economy and the political sphere. In this world, public sector debt would be much higher and the public sector’s grip on the economy much greater, while globalisation would be forced into a major retreat. As a result, labour and firms would gain much more pricing power. And governments could be tempted to keep financing costs artificially low, allowing the inflation tax to reduce the real value of their debt, possibly supported by forms of financial repression.” – bto: Bingo, da haben wir Coronomics aus dem Mund der BIZ.

- “At that point, it would be critical that central banks should be able to operate independently to pursue their mandate in order to resist any possible pressures not to increase interest rates.” – bto: Genau, so ist es!

- “So far, the objectives of central banks and governments have coincided. Cooperation has come naturally. Central banks have not deviated from the pursuit of price and financial stability. But should inflationary pressures emerge at some point, tensions could arise. Then, the main institutional safeguard against such pressure would be central bank independence – a safeguard that raises the bar for successful government intervention. In this context, growing calls for ‘monetary financing’, regardless of their motivation, raise the risk of inching economies down that path. If taken far enough, this process could over time dent confidence in a country’s monetary institutions, exacting a high price in the pursuit of ephemeral short-run output gains. After all, the hard-won anti-inflation credibility of central banks has been instrumental during the recent crisis in allowing them to cross a number of previous “red lines” to stabilise the financial system and the economy.” – bto: Weil das kommen wird, sollte Deutschland unbedingt mitmachen!

Quelle: BIZ

- “Today, more than ever, a premium needs to be put on keeping fiscal policy on a sustainable path through timely consolidation. The limits of monetary policy need to be recognised, as well as the importance of preserving and extending the post-GFC gains in strengthening the financial system’s resilience. Finally, renewed efforts are needed to implement the necessary structural economic reforms, a path that has proved quite elusive both before and after the GFC. This calls, above all, for taking a longer-term view than hitherto. It means avoiding shortcuts and not being tempted by policies that, while beneficial in the short term, may raise significant costs in the long term. After all, however distant it may appear, the future eventually becomes today.” – bto: Die Hoffnung stirbt bekanntlich zuletzt.

- “There are limits to how far the boundaries between fiscal and monetary policies can be pushed without running the risk of undermining the central bank’s credibility. Trust and confidence in central banks are arguably their most important assets. It is precisely because of this hard-won trust and confidence that central banks have been able to cross a number of previous red lines to restore stability during this crisis. Preserving that confidence is essential.” – bto: richtig.

Nun kann der nüchterne Beobachter auch sagen: Wenn das alles nicht kommt, was hier gefordert wird, was ist die Schlussfolgerung. Genau: Monetarisierung, finanzielle Repression, Inflation … und Vertrauensverlust.