Eiszeit an den Kapitalmärkten – Fortsetzung

Bereits am Montag habe ich an dieser Stelle die Eiszeit an den Kapitalmärkten beschrieben. Heute nun Teil zwei, den es eigentlich nicht bräuchte. Es ist bereits vorher Lesern von bto bekannt gewesen, dass bei heutigem Niveau nur noch maue Renditen zu erwarten sind – auch aus den Kommentaren von John Hausmann, die immer wieder lesenswert sind:

→ „The Ponzi Economy“

→ US-Aktien so teuer wie nie

→ Erwartete Renditen: negativ – egal, wie man es betrachtet

Heute nun das Update!

- “In all of the exuberance about low interest rates ‚justifying‘ elevated equity valuations, what’s striking is how little investors appear to appreciate the Morton’s Fork – two opposing possibilities that lead to the identical outcome – they’re actually facing. Whether one believes that economic growth will remain dismal and interest rates will remain low, or that economic growth will accelerate and interest rates will gradually normalize, the inevitable outcome for market returns is likely to be very much the same.”

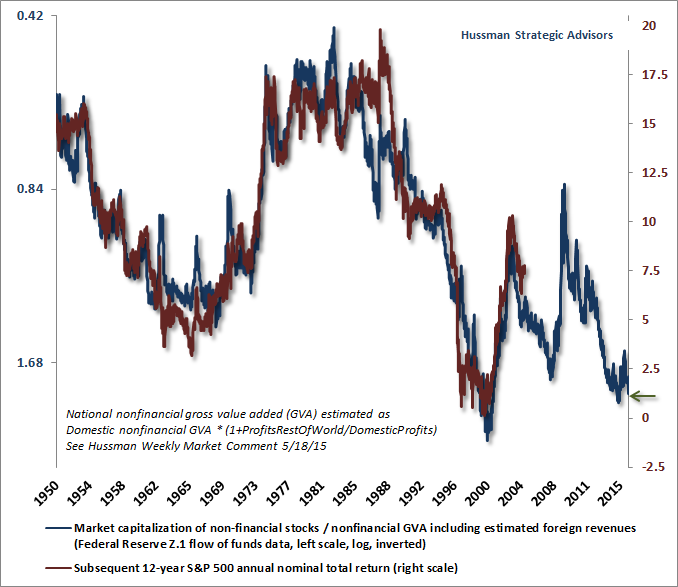

- “Specifically, investors should fully expect that over the coming 12-year horizon, the nominal total return of the S&P 500 will average less than 1.5 % annually.”

- “(…) the most historically reliable valuation measures we identify are consistent with expected 12-year S&P 500 total returns averaging less than 1.5 % annually.”

Quelle: John Hussman

- “Put simply, years of yield-seeking speculation have already driven stock valuations to levels where prospective 10-12 year total returns for the S&P 500 are likely to be no different than the near-zero yields available on Treasury securities. The main difference is that equities have several times the volatility and downside risk.”

- “One striking feature of market history is that the correlation between 10–12 year S&P 500 nominal total returns and nominal GDP growth over the same period is quite literally zero. Instead, market returns on that horizon are almost entirely determined by the starting level of valuation on reliable measures such as MarketCap/GVA. While there’s strong evidence that investors respond to pastnominal GDP growth in setting the level of interest rates and equity valuations, it bears repeating that once those valuations are set, subsequent investment returns are essentially baked-in-the-cake.”

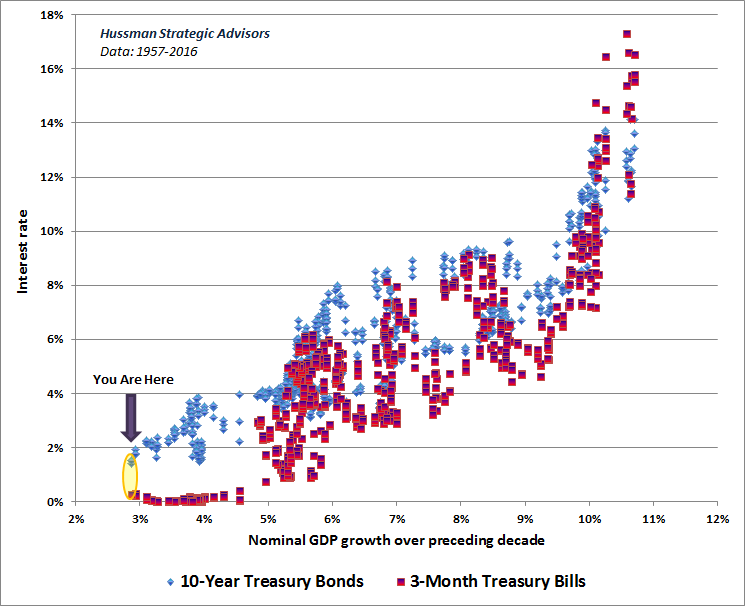

- “(…) it becomes clear that investors are suckers for recent experience. Give investors an extended taste of low nominal economic growth over a 10-year period, and they systematically drive interest rates lower, including long-term interest rates. The kicker here is that past nominal growth rates are very weakly correlated with subsequent nominal growth rates (the correlation between past 10-year and subsequent 10-year nominal GDP growth is less than 0.25). So investors tend to set interest rates by attending to the most recent thing they see in the rear-view mirror. The chart below illustrates this tendency, in post-war data, for investors to set interest rates largely in response to past growth in nominal GDP.”

Quelle: John Hussman

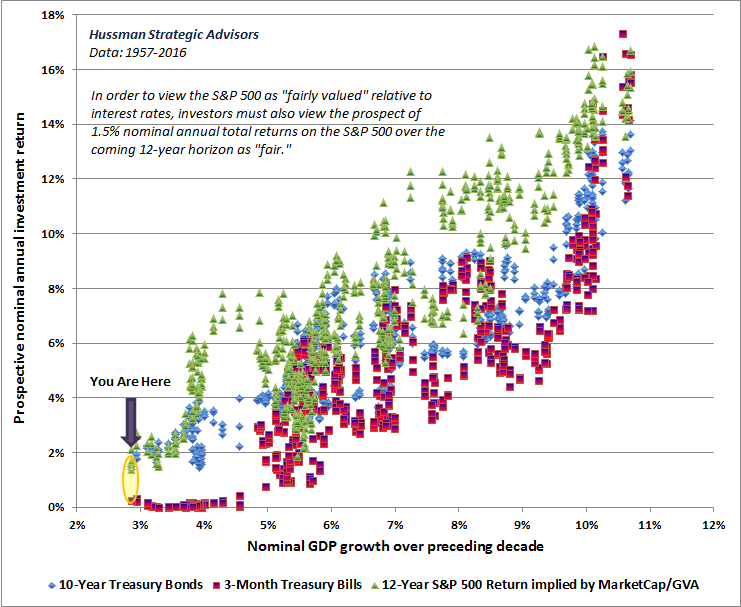

- “The following chart adds another series, which is the prospective 12-year S&P 500 total return implied by MarketCap/GVA (which has a 93 % correlation with actual subsequent market returns on that horizon). Note that prospective equity returns generally have a wide scatter. For example, the dismal 12-year returns we observe at present were also observed at the 2000 market peak, when trailing nominal GDP growth was close to 6 % annually. The compressed block of green points at the bottom left reflect the lowest level of nominal growth observed in the post-war era, along with equally dismal prospective investment returns. Those awful 10-12 year prospects for investment returns in stocks and bonds are now baked in the cake, and as noted above, will be largely independent of where economic growth goes from here. Take the green, red, and blue points together, and the combined result is that the expected 10–12 year return on a conventional portfolio mix (60 % stocks, 30 % bonds, 10 % cash) has plunged to one of the lowest levels in history.”

Quelle: John Hussman

- “If no material economic shock unfolds in the coming years, uninspiring economic growth and depressed interest rates could hold valuations at levels consistent with 12-year prospective returns in a narrower range of about 2–6 % annually. That, in turn, would imply shallower, but probably more frequent retreats on the order of 15–30 %, but without the kind of wipeout that would take valuations toward more durable historical norms. We should certainly allow for that possibility, which we would still expect to provide reasonably frequent opportunities to accept market exposure.”

- “I think it’s very ill-advised to assume that the equity market will escape regular and material corrections altogether, or that it will enjoy any durable returns from current valuations. Current market conditions couple the third most extreme valuations in history (next to 2000 and 1929, in that order) with extraordinarily high levels of debt (much of it covenant-lite, providing bondholders little defense in the event of bankruptcy). My sense is that this will end quite badly, but we don’t need to rely on spectacular outcomes. We’ll take our evidence as it comes. “

“Too many investors seem mesmerized by the idea that central banks have near-magical powers, never fully defined, and never clearly articulated. The best advice I can offer is this: put your assumptions into words, and then take them to the data to make sure that what you believe is actually true.”